Across the long arc of human history, knowledge has never been evenly preserved. Ideas have burned with cities, vanished with empires, dissolved in humidity, and crumbled into dust with the fragile materials that carried them. Entire philosophies, scientific treatises, literary masterpieces, and historical records have been lost—not because they lacked value, but because the physical structures that housed them could not survive time, war, or neglect.

Ancient libraries were more than collections of scrolls or manuscripts. They were engines of intellectual civilization. They gathered knowledge from distant lands, translated languages, compared cultures, and preserved discoveries that might otherwise have vanished forever. Within their walls, mathematics advanced, astronomy evolved, medicine matured, and philosophy deepened. They represented humanity’s collective memory—organized, protected, and studied.

When these libraries disappeared, the losses were immeasurable. Their destruction did not merely remove books; it erased conversations across generations. Entire scientific traditions fragmented. Cultural continuity broke. Knowledge had to be rediscovered, reinvented, or reconstructed centuries later.

Yet traces remain. Archaeology, historical scholarship, and surviving fragments allow us to glimpse what once existed. These lost libraries stand as reminders of both human intellectual ambition and the fragility of preservation. Each one tells a story not only of learning, but of vulnerability.

Below are eight of the most significant ancient libraries that once held vast reservoirs of knowledge—repositories whose disappearance reshaped the course of intellectual history.

1. Library of Alexandria

Few institutions in human history have captured the imagination as powerfully as this legendary center of learning. Established during the Hellenistic period, it was designed to collect all the knowledge of the known world. Its founders envisioned a universal archive—an ambitious attempt to gather every text that could be acquired through travel, trade, diplomacy, or copying.

The library functioned as part of a larger scholarly complex known as the Mouseion, a research institution where scholars lived, worked, and taught. It attracted mathematicians, astronomers, physicians, and philosophers from across the Mediterranean and beyond.

Texts were written primarily on papyrus scrolls, stored in enormous quantities. Ships arriving in the harbor were sometimes searched for manuscripts, which were copied for the collection. The range of knowledge preserved there was extraordinary: geometry, astronomy, geography, literature, medicine, engineering, and philosophy.

Among the scholars associated with this intellectual environment were individuals who made foundational contributions to science. Calculations of Earth’s circumference, developments in geometry, and advances in textual criticism all flourished within this scholarly ecosystem.

The library’s decline was gradual rather than instantaneous. Political instability, warfare, and shifting economic power eroded institutional support over time. Portions were damaged or destroyed during conflicts, and eventually the great collection disappeared entirely.

What was lost cannot be fully measured. Many works known only by title once existed there. Some scientific theories recorded in antiquity vanished and had to be rediscovered centuries later. The disappearance of this library remains one of the most profound intellectual losses in recorded history.

2. Library of Pergamum

In ancient Anatolia, a powerful rival to Alexandria emerged. This library formed the intellectual centerpiece of the city of Pergamum, a thriving cultural and political center of the Hellenistic world.

Its rulers invested heavily in scholarship, determined to create a collection that could rival the greatest repositories of knowledge. The library became famous not only for its holdings but also for its role in the development of writing materials. According to historical tradition, restrictions on papyrus exports encouraged the refinement of parchment, a writing surface made from treated animal skin. This durable material allowed manuscripts to be preserved longer and copied more easily.

The library was integrated into a broader cultural landscape that included temples, theaters, and academic spaces. Scholars engaged in literary criticism, philosophical analysis, and scientific study. The environment fostered the classification and organization of texts, reflecting an increasingly systematic approach to knowledge management.

At its height, the collection reportedly contained hundreds of thousands of volumes. While ancient numerical estimates must be treated cautiously, there is no doubt that it was one of the largest and most influential libraries of antiquity.

Political shifts eventually led to the dispersal of the collection. Manuscripts were transferred, relocated, or lost over time as empires rose and fell. The intellectual life that once animated the city gradually faded, leaving behind ruins and fragments.

The legacy of this library lies not only in its lost texts but also in its contributions to manuscript preservation and scholarly organization—practices that shaped later library traditions.

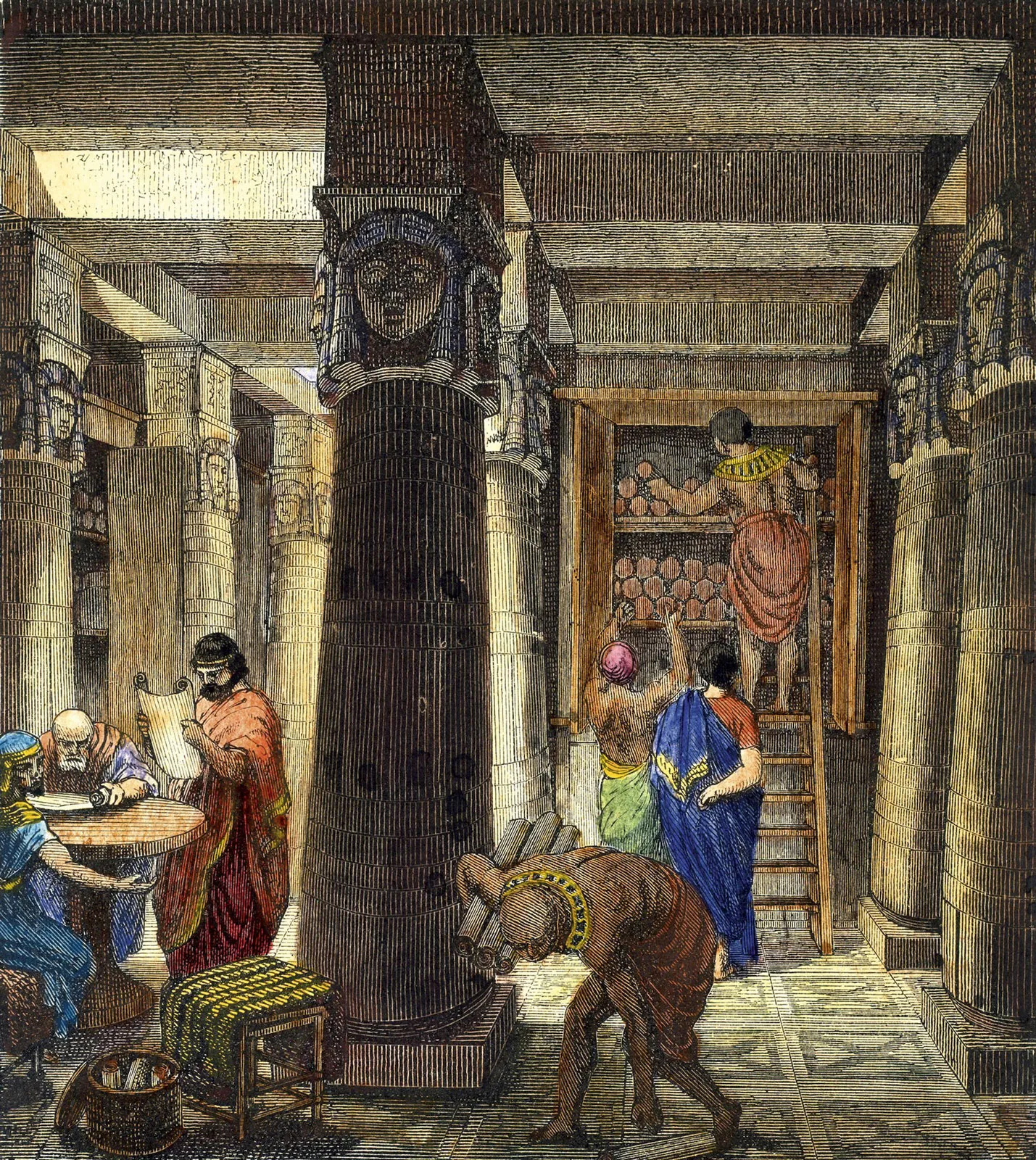

3. Library of Ashurbanipal

In the ancient city of Nineveh, capital of the Neo-Assyrian Empire, a king with an unusual passion created one of the earliest systematically organized libraries known to history. Ashurbanipal, who ruled in the seventh century BCE, was deeply committed to scholarship and literacy.

Unlike many royal collections, this library focused on preservation through durability. Instead of papyrus or parchment, texts were inscribed on clay tablets using cuneiform script. Once baked or dried, these tablets could survive fire and environmental decay far better than organic writing materials.

The collection included literary works, administrative records, scientific observations, religious texts, and lexical lists. Among its most famous contents is the Epic of Gilgamesh, one of the oldest surviving works of literature.

Ironically, the destruction of Nineveh contributed to the preservation of the library. When the city fell, buildings collapsed and fires burned. The heat baked many clay tablets, hardening them permanently. Buried under debris, they remained preserved for millennia.

Modern archaeological excavation uncovered tens of thousands of fragments. Scholars painstakingly reassembled them, reconstructing texts that would otherwise have vanished completely.

This library offers a rare window into the intellectual life of ancient Mesopotamia. It demonstrates that systematic knowledge preservation existed long before classical Greece and that written tradition in the Near East was vast and sophisticated.

4. Nalanda Library

Within one of the world’s earliest great residential universities stood a library complex of astonishing scale. Nalanda functioned as a major center of learning for centuries, attracting students and scholars from across Asia.

The library consisted of multiple large buildings filled with manuscripts covering philosophy, mathematics, medicine, linguistics, astronomy, and religious studies. Scholars engaged in debate, research, and translation. Knowledge circulated across cultural and linguistic boundaries.

Texts were preserved on palm-leaf manuscripts, a material requiring careful maintenance due to vulnerability to humidity and decay. Preservation involved copying and recopying—an ongoing process of renewal.

Accounts from historical sources describe vast collections rising several stories high. The scale of the holdings reflected the university’s central role in intellectual exchange across the region.

The destruction of the library during military invasion in the twelfth century marked a catastrophic loss. Reports describe manuscripts burning for extended periods due to the immense volume of material.

The disappearance of this collection disrupted scholarly continuity across large parts of Asia. Many works known to have existed there no longer survive in any form.

Nalanda represents one of the greatest examples of academic culture in the premodern world—an institution where knowledge was not only preserved but actively produced and transmitted.

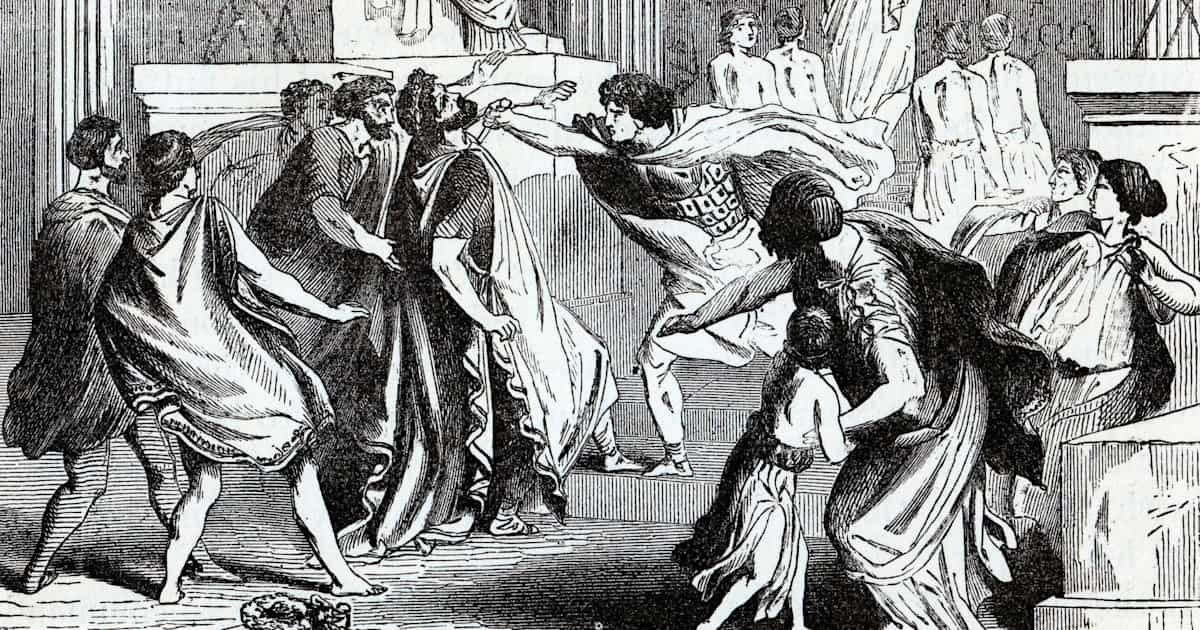

5. House of Wisdom

In medieval Baghdad, an extraordinary intellectual institution emerged during a period of intense scholarly activity. This center functioned as a translation academy, research institute, and library combined.

Scholars working there translated works from Greek, Persian, and other traditions into Arabic. Mathematics, astronomy, medicine, and philosophy flourished through cross-cultural synthesis.

Astronomical observations were conducted with increasing precision. Mathematical concepts evolved, including developments that would later influence global scientific practice. Knowledge did not simply accumulate—it transformed.

Manuscripts were copied, compared, and analyzed. Scholars debated interpretations and refined theories. The institution embodied the principle that knowledge grows through interaction between cultures.

Its destruction during the Mongol conquest of Baghdad in the thirteenth century brought an abrupt end to this intellectual flowering. Countless manuscripts were lost, many representing unique translations or original research.

The House of Wisdom symbolizes the power of scholarly collaboration across civilizations—and the devastating consequences when such centers vanish.

6. Imperial Library of Constantinople

As the Eastern Roman Empire preserved and transformed classical traditions, this imperial library became a vital guardian of ancient Greek and Roman literature.

Manuscripts were copied onto parchment codices, a format more durable than scrolls. Scholars engaged in preservation, editing, and commentary. Many classical texts survived into the medieval period only because they were maintained within this institutional framework.

Fires and political upheavals repeatedly damaged the collection. Despite efforts at restoration, cumulative losses gradually reduced the holdings.

When the city eventually fell in the fifteenth century, remaining manuscripts were scattered, destroyed, or transferred. Some texts entered European circulation, contributing to the Renaissance. Others vanished permanently.

This library served as a bridge between antiquity and the medieval world, preserving intellectual continuity across centuries of transformation.

7. Library of Celsus

Constructed as both a monumental tomb and a public library, this architectural masterpiece stood at the heart of a major Roman city. Its facade reflected the cultural prestige attached to knowledge in the Roman world.

Manuscripts were stored in wall niches designed to regulate temperature and humidity. The library housed thousands of scrolls, representing literary, philosophical, and administrative works.

The structure itself demonstrated advanced architectural planning, combining aesthetic grandeur with functional design for preservation.

Earthquakes and invasions eventually damaged the building, and its collection disappeared. Today the reconstructed facade stands as a powerful visual reminder of Rome’s intellectual culture.

The library exemplifies how knowledge could be embedded within civic identity—celebrated publicly and architecturally.

8. Monte Cassino Library

Founded within a monastic community, this library became one of medieval Europe’s most important centers of manuscript preservation. Monks copied texts meticulously, preserving classical literature, religious writings, and scholarly works.

Scriptoria within the monastery functioned as production centers for books. Each manuscript represented hours of labor and extraordinary attention to detail.

Repeated destruction through warfare—including catastrophic damage in the twentieth century—led to immense losses. Yet earlier copying efforts ensured that some texts survived elsewhere.

The history of this library illustrates how knowledge can persist through replication even when physical repositories are destroyed.

The Fragility and Power of Preservation

These libraries once held vast intellectual landscapes. Their destruction reminds us that knowledge is never permanently secure. Preservation requires material stability, institutional support, and cultural commitment.

When libraries vanish, humanity does not merely lose information—it loses pathways of thought, lines of inquiry, and voices from the past.

The Continuing Legacy of Lost Knowledge

Modern archives, digital repositories, and conservation science reflect lessons learned from ancient losses. Preservation today involves climate control, redundancy, and global collaboration.

Yet even now, knowledge remains vulnerable—to conflict, neglect, and environmental change.

The Memory That Remains

Though their shelves are empty, these ancient libraries still speak. Through archaeology, surviving fragments, and historical reconstruction, they remind us that the pursuit of knowledge has always been central to human civilization.

They stand as monuments not only to what humanity learned—but to what it once knew, and no longer remembers.