Roughly 2.6 million years ago, Earth entered a frigid era that would stretch across millennia, sculpting continents, redirecting evolution, and shaping the fate of countless species. This epoch—known as the Pleistocene Ice Age—was not a single freeze but a pulsating rhythm of glaciations and interglacial periods, where enormous sheets of ice repeatedly advanced and retreated over vast swaths of the planet.

Yet somehow, amid this hostile and ever-changing climate, one small, fragile species—Homo sapiens—not only endured, but emerged triumphant. While mammoths and saber-toothed cats vanished into extinction, humans persisted, adapted, and flourished. The story of how we survived the Ice Age is a profound testament to ingenuity, resilience, and the unrelenting will to live.

This tale isn’t just about physical endurance—it’s about innovation, cooperation, and the unique human ability to shape culture as a survival tool. Through bones buried in frozen tundra, tools etched from flint, and DNA preserved in ancient remains, science is slowly piecing together the astonishing story of Ice Age survival.

The Icy World We Inhabited

During the height of the last glacial maximum—around 20,000 years ago—massive glaciers covered much of North America, Europe, and Asia. These ice sheets, sometimes more than two miles thick, transformed the landscape into a barren, frozen wilderness. Temperatures were on average 10 to 20 degrees Celsius colder than today. In areas now teeming with life, snow covered the ground year-round, and powerful winds scoured the land.

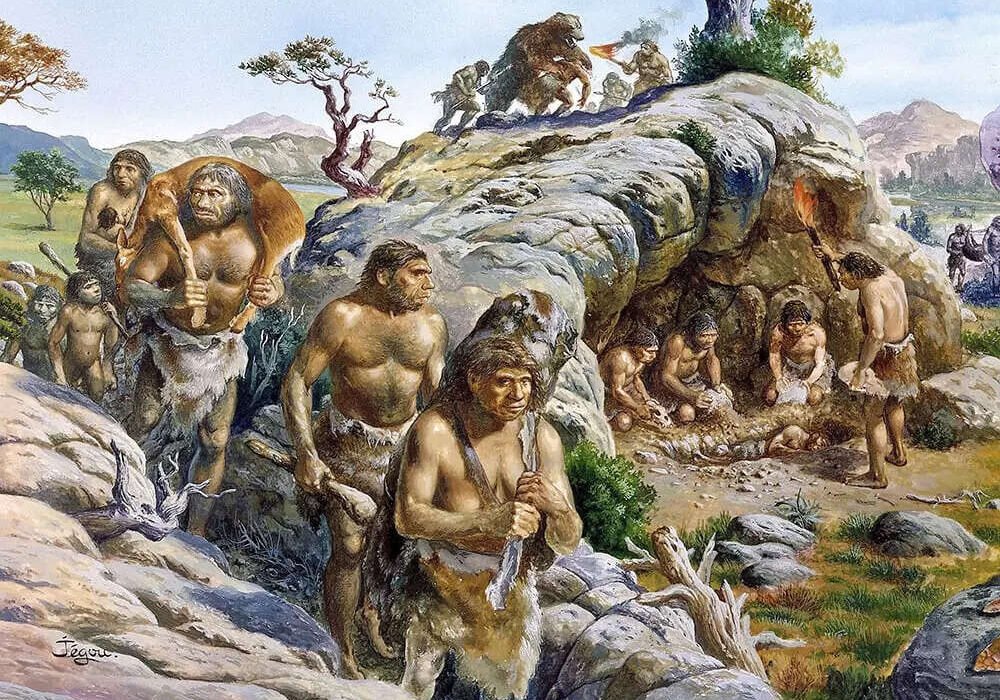

It was a world where survival was not guaranteed. Food was scarce, predators were enormous and relentless, and shelter was difficult to find. In this perilous environment, Homo sapiens were not alone. Other human species, like Neanderthals and Denisovans, also walked the Earth. But only one would make it to the modern era.

What allowed our ancestors to succeed where others failed?

Shelter in the Shadows of Ice

At the heart of Ice Age survival was the need for protection—not just from predators, but from the cold itself. Unlike mammoths with their dense fur or arctic foxes with insulating tails, humans had soft, hairless skin ill-suited for glacial winters. Yet from their earliest days, humans demonstrated an uncanny knack for manipulating their environment.

Archaeological findings show that Ice Age humans used natural shelters such as caves and rock overhangs whenever possible. These offered insulation from the cold winds and remained relatively warm during brutal winters. In areas where caves were scarce, humans began to build their own shelters—initially from bones, wood, hides, and even blocks of snow.

Perhaps the most striking example of Ice Age architecture is the circular dwellings made from mammoth bones found in Eastern Europe. These incredible structures, some over 20,000 years old, reveal an early mastery of engineering. Bones formed the frame, while hides and turf acted as insulation. Fires burned at the center, radiating warmth and providing a communal hub for cooking, storytelling, and ritual.

Mastering Fire: Nature’s Most Primal Tool

The control of fire predates the Ice Age, but during this era, fire became more essential than ever. It wasn’t just a source of warmth—it was survival itself. Fire allowed humans to cook tough, frozen meat, render fat for calories, sterilize tools, and protect their camps from nocturnal predators. It extended daylight during long polar nights and helped dry clothing soaked by snow.

But keeping a fire alive in sub-zero temperatures was no easy task. Evidence suggests that Ice Age humans carefully tended their fires, carried embers when they moved, and even stored dry fuel inside their shelters. Flint and pyrite, used to spark fires, were treasured items. The flame, once kindled, became a communal lifeline—kept alive at all costs.

Clothing: The Invention of the Portable Shelter

The difference between life and death in Ice Age conditions often hinged on how well one could insulate the human body. While earlier hominins may have wrapped themselves in crude hides, Ice Age humans took clothing to new heights of sophistication. Sewing needles carved from bone appear in the archaeological record as early as 40,000 years ago, and they revolutionized our ability to craft tailored garments.

Skins from animals like reindeer, wolves, and bears were tanned and stitched together to form layered clothing systems. A base layer of soft inner fur provided warmth, while outer hides offered wind protection. Footwear was carefully designed to insulate and maintain grip on icy surfaces. The ability to make well-fitted clothing meant that humans could migrate further north and inhabit previously unreachable terrain.

In essence, clothing became a wearable shelter—a technology that made the human body more adaptable than any other species of the time.

The Art of the Hunt

Ice Age humans were hunter-gatherers, and during the glacial periods, hunting dominated daily life. Vast herds of megafauna—mammoths, bison, reindeer, and woolly rhinoceroses—roamed the frozen plains. These animals were both a threat and a resource, and hunting them demanded not just courage, but extraordinary skill.

Weapons evolved rapidly during this period. Simple wooden spears gave way to stone-tipped javelins, atlatls (spear throwers), and eventually bows and arrows. These innovations allowed hunters to strike from greater distances and with more force. Traps, pits, and drive-hunting techniques helped entire communities bring down massive animals.

A single mammoth could feed a tribe for weeks. Its bones became building materials, its hide transformed into clothing, and its sinews repurposed as bowstrings or thread. Hunting wasn’t just an act of survival—it was the bedrock of Ice Age economies, and it required complex cooperation, communication, and planning.

Food Beyond the Hunt

While large game provided calories and materials, humans were not solely reliant on mammoth steaks. The Ice Age menu was surprisingly diverse. People gathered nuts, roots, berries, and edible tubers when available. Fish, birds, and smaller mammals were hunted or trapped. In coastal areas, shellfish and marine mammals offered sustenance year-round.

Importantly, Ice Age humans began to preserve food—smoking, drying, or freezing meat in natural ice. These techniques allowed them to store energy during times of abundance and survive the harshest seasons when fresh resources were scarce.

Fat-rich foods, in particular, were essential. The human body requires fat to survive extreme cold, and Ice Age hunters prized blubber and marrow. Bone-crushing tools were developed not just for weaponry but to access the calorie-dense interiors of long bones.

A Network of Survival

One of the most remarkable traits of Ice Age humans was their ability to form extensive social networks. Even in isolated, frozen environments, humans maintained contact with neighboring bands. Tools, beads, shells, and other artifacts found hundreds of miles from their place of origin suggest that trade was thriving, even during the Ice Age.

These networks served many purposes. They facilitated the exchange of ideas and technologies, such as new tool-making techniques or clothing designs. They also helped people find mates, form alliances, and maintain genetic diversity. In times of famine or disease, neighboring groups could offer support or take in members.

This social web may have been the deciding factor that allowed Homo sapiens to survive while Neanderthals, who had smaller and more isolated populations, faded away.

The Power of Language and Symbolism

Survival in the Ice Age wasn’t just about physical adaptation—it was also deeply cultural. Humans during this time began to express themselves through art, ritual, and possibly the first true languages.

The walls of caves across Europe, from Lascaux in France to Altamira in Spain, bear vivid illustrations of Ice Age life. Mammoths, lions, bison, and human figures leap across the walls, painted in ochre, charcoal, and iron oxide. These were not mere decorations—they were symbols, perhaps of stories, beliefs, or hunting strategies.

The emergence of symbolic thought may have played a critical role in survival. It allowed for better planning, more effective teaching, and the development of complex rituals. Burial sites from the Ice Age contain grave goods—tools, beads, animal bones—indicating a belief in an afterlife or the importance of the dead. These rituals may have strengthened social bonds and provided psychological resilience in a harsh world.

Migration and the Spirit of Exploration

The Ice Age was a time of great movement. As glaciers advanced and retreated, humans followed the animals and the climate, adapting to new environments along the way. This migration wasn’t random—it was strategic, bold, and often perilous.

From Africa, humans expanded into Europe, Asia, and eventually the Americas. They crossed ice bridges, scaled mountain ranges, and adapted to deserts, tundras, and dense forests. Each new environment required unique adaptations, yet humans met these challenges with relentless ingenuity.

Their journeys laid the foundation for the global human population. The descendants of these Ice Age explorers would settle every continent, forming the rich tapestry of cultures and civilizations that followed.

Genetics: Tracing the Legacy of Ice Age Survivors

Modern genetic studies offer powerful insights into Ice Age survival. DNA from ancient human remains tells a story of interbreeding, adaptation, and resilience. For example, modern humans carry traces of Neanderthal and Denisovan DNA—evidence of ancient encounters during Ice Age migrations.

Some of these inherited genes likely provided survival advantages, such as improved immune responses or adaptations to cold. Genetic markers also reveal ancient bottlenecks—moments when human populations dwindled to dangerously low levels, only to rebound through migration and innovation.

Today, the genetic legacy of Ice Age humans lives on in every person alive, a living testament to their endurance.

Lessons From the Deep Freeze

The Ice Age was an epic trial, a crucible that forged humanity into what it is today. Our ancestors didn’t just survive; they learned, adapted, and laid the groundwork for future civilizations. They invented clothing, built homes, shaped tools, created art, and formed communities strong enough to weather the harshest of climates.

Their story is not one of mere endurance but of triumph through creativity, cooperation, and vision. The very qualities that allowed humans to survive the Ice Age are those we still carry: adaptability, imagination, and the instinct to connect with one another.

In a modern world grappling with climate change, resource scarcity, and global uncertainty, the lessons of the Ice Age remain startlingly relevant. Our ancestors remind us that while nature can be cruel, humanity’s spirit is resilient, innovative, and—most importantly—unbreakable.