Among the countless gods of ancient Greece, few inspire as much fascination and dread as Hades, the ruler of the dead and sovereign of the Underworld. His name alone carried such weight that the Greeks often avoided speaking it, fearing that to do so would draw his gaze. Instead, they called him euphemistic titles—Plouton (the giver of wealth), Aidoneus (the unseen one), or simply “the host below.” Though often misunderstood as a god of evil or destruction, Hades was neither demon nor tormentor. Rather, he was one of the most essential deities in Greek thought: the keeper of balance, the guardian of souls, and the unyielding lord of the afterlife.

Hades’ story is not one of cruelty or bloodlust but of inevitability and order. In him, the Greeks saw the ultimate certainty—that all living beings must eventually pass beyond the veil. His kingdom was not hell in the Christian sense, nor was he Satan. Instead, Hades presided over a vast, structured realm where every soul found its destiny according to the deeds of its mortal life. To understand him is to enter into the heart of Greek mythology, where death is not merely an ending, but a continuation, a realm of its own rules and mysteries.

Birth Among the Titans

Hades’ origin story begins in the primordial chaos of creation. He was the son of the Titans Cronus and Rhea, born alongside his siblings—Zeus, Poseidon, Hera, Demeter, and Hestia. His childhood, however, was overshadowed by terror. Cronus, fearing that one of his children would overthrow him as he had overthrown his own father Uranus, swallowed each newborn whole.

Like his brothers and sisters, Hades was devoured, condemned to darkness within his father’s belly. Salvation came when Zeus, the youngest sibling, was hidden away by Rhea and later forced Cronus to disgorge his offspring. The freed children rose together against their tyrannical father, waging the great cosmic conflict known as the Titanomachy.

When victory was secured, the three brothers—Zeus, Poseidon, and Hades—divided the cosmos by lot. Zeus claimed the sky, Poseidon the sea, and Hades was given the Underworld, the unseen domain beneath the earth. Far from being a punishment, this realm was of equal importance to the heavens and the oceans. It was Hades’ duty to govern the dead, ensuring the cycle of life and death would continue unbroken. Thus began his reign as the Lord of the Underworld.

The Nature of Hades

To the Greeks, Hades embodied inevitability. He was not malevolent but implacable, a god who did not bargain or yield. Once a mortal entered his realm, there was no escape unless he willed it. He represented the permanence of death and the inescapable truth that even kings and heroes could not defy mortality.

Yet Hades was also called Plouton, the giver of wealth. This reflected not only the riches of the earth—precious metals, fertile soil, hidden treasures—but also the idea that death replenishes life. The crops that grew from the ground were nourished by what lay buried beneath. In this way, Hades was not only the god of the dead but also a god of abundance, for all wealth and sustenance ultimately emerged from his dark domain.

Despite his immense power, Hades rarely left the Underworld. Unlike Zeus with his thunderbolts or Poseidon with his storms, Hades seldom interfered in the affairs of the living. He was a god of constancy and distance, feared but not worshiped with the same fervor as others. Temples to him were rare, and sacrifices to him were performed with solemn secrecy.

The Realm of the Dead

The Underworld over which Hades ruled was a vast, intricate kingdom. It was entered through caverns, cracks in the earth, or across the rivers that formed its borders. Souls of the dead were led there by Hermes Psychopompos, the guide of souls, and carried across the river Styx by the ferryman Charon, provided they had been buried properly with a coin for passage.

The Underworld was not a single place but a collection of regions:

- The Asphodel Meadows, where ordinary souls wandered in a shadowy existence.

- The Elysian Fields, a paradise reserved for the virtuous and heroic, bathed in eternal spring.

- Tartarus, the deepest abyss, where the wicked and the enemies of the gods endured eternal punishment.

- The Isle of the Blessed, later introduced as a place of rebirth for souls who had lived righteous lives three times over.

Hades presided over this entire realm, but he was not alone. His kingdom teemed with figures both divine and monstrous—the three-headed guard dog Cerberus, the judges of the dead (Minos, Rhadamanthys, and Aeacus), the spirits of vengeance called the Erinyes, and countless shades of mortals awaiting their fates.

This vision of the afterlife reflected Greek values: the inevitability of death, the importance of justice, and the moral weight of one’s deeds in life. Under Hades’ watch, balance was preserved.

The Abduction of Persephone

Perhaps the most famous story involving Hades is his union with Persephone, the daughter of Demeter, goddess of agriculture. The myth tells that Hades, smitten by her beauty, abducted her from a meadow and carried her into his realm to be his queen.

Demeter’s grief was profound. She scoured the earth searching for her lost child, neglecting her divine duty and causing crops to wither. The world grew barren, and famine threatened humankind. Only when Zeus intervened was a compromise reached: Persephone would spend part of the year with her mother and part with Hades.

This myth was more than a tale of abduction; it was a symbolic explanation of the seasons. When Persephone dwelled with Hades, Demeter mourned, and winter gripped the earth. When Persephone returned, Demeter rejoiced, and spring blossomed once more.

Persephone’s role as Queen of the Underworld transformed her from a maiden of innocence into a powerful figure of duality—both life-bringer and death-bride. Together, Hades and Persephone ruled over the mysteries of mortality and rebirth.

Misunderstood God of the Dead

In later times, Hades became conflated with the idea of hell and the devil, especially under the influence of Christian thought. Yet in Greek religion, he was not evil. Unlike gods who inflicted plagues or stirred storms, Hades did not actively harm mortals. He simply received them when their time came.

He did not choose who lived or died—that power belonged to the Moirai, the Fates. He did not torment souls personally—that was the work of other deities and spirits within his realm. His role was to maintain order, ensuring that the dead remained in their rightful place and the living respected the boundaries of mortality.

To the Greeks, this made Hades a god of solemn necessity rather than cruelty. He was feared because he symbolized the unknown, the unreturnable, but he was also respected as the guardian of cosmic balance.

Heroes Who Defied Him

Although Hades was unyielding, Greek myths recount rare occasions when mortals or demigods entered his domain and confronted him. These stories highlight both his authority and the daring of those who sought to challenge death itself.

Orpheus, the legendary musician, descended into the Underworld to retrieve his beloved Eurydice. His music softened even Hades’ stern heart, and the god allowed Eurydice to return—on the condition that Orpheus not look back until they had both reached the surface. Tragically, Orpheus turned too soon, and Eurydice was lost forever.

Heracles (Hercules), during his Twelve Labors, was tasked with capturing Cerberus. He entered the Underworld with Hades’ permission and brought the beast back to the living world, proving his unmatched strength and courage.

Perseus and Theseus also attempted to meddle with Hades’ realm. Theseus sought to abduct Persephone but was punished with entrapment in the Underworld until later freed by Heracles.

Such tales reveal that though Hades was stern, he could be swayed by courage, artistry, or divine destiny. Yet they also reinforced the lesson that death is not a realm to be trifled with.

Symbols and Sacred Animals

Hades was often depicted with certain symbols that revealed his nature. The bident, a two-pronged scepter, marked his authority as ruler of the Underworld. The helm of darkness, a gift from the Cyclopes during the Titanomachy, rendered him invisible and symbolized his unseen dominion.

The cypress tree was sacred to him, associated with mourning and death. Black animals, especially sheep, were offered in sacrifice. His most famous companion was Cerberus, the monstrous hound with three heads and a serpent’s tail, who prevented the dead from escaping.

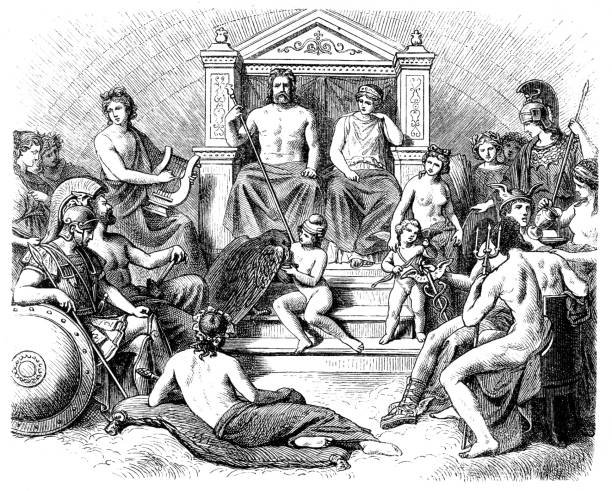

Unlike other gods, Hades was rarely represented as flamboyant or violent. His depictions in art show him as solemn, regal, and immovable, seated upon a dark throne beside Persephone.

The Mysteries of Hades and Persephone

The myth of Hades and Persephone formed the foundation of the Eleusinian Mysteries, secret religious rites practiced in honor of Demeter and Persephone. Initiates were taught sacred truths about life, death, and the afterlife—truths that were never written down but believed to promise hope beyond death.

Hades, though often excluded from direct worship, was central to these mysteries. His role in the cycle of death and rebirth offered a vision of immortality, a comfort against the fear of nothingness. For the Greeks, the Underworld was not only a place of shadow but also a place of renewal.

Hades in Roman and Later Thought

When Greek mythology blended into Roman culture, Hades became known as Pluto, the god of wealth. Roman poets like Virgil and Ovid expanded upon his myths, shaping the later Western imagination of the afterlife.

With the rise of Christianity, however, Pluto was increasingly identified with the concept of Hell and the devil, distorting his original role. The medieval world saw him as a figure of punishment rather than inevitability. Only in modern scholarship has Hades been reclaimed as a more complex, balanced deity—a figure embodying both dread and necessity, loss and continuity.

The Eternal Reign of the Lord Below

In the end, Hades is not merely the god of death. He is the keeper of boundaries, the guarantor of order, and the reminder of life’s fragility. Without him, the world of the living would have no contrast, no sense of meaning. His silent presence gave weight to existence itself, for to live fully was to know that Hades awaited.

To the Greeks, he was a figure to fear, but also one to respect. In Hades, they saw the mystery that binds all creatures together—the journey into the unknown, the return to the earth, the cycle of ending and renewal. His kingdom was not a place of evil but of inevitability, a mirror in which humanity could confront its deepest truths.

Thus, Hades remains one of the most haunting and profound figures in mythology. His story reminds us that death is not only an end but also part of the greater order of life, that beneath fear lies continuity, and that in the silence of the Underworld, there is a god who watches, steadfast and eternal.