Among the many tales of Greek mythology, some dazzle with their epic battles, while others stir the heart with their poignant intimacy. Few, however, weave together wonder, mystery, art, and desire as beautifully as the story of Pygmalion and Galatea—a myth in which love transcends the boundary between cold stone and warm flesh. It is the tale of an artist who, disillusioned by the flaws of human nature, sculpts the perfect woman from ivory, only to find himself falling in love with his own creation. Through divine intervention, his impossible yearning is answered: the statue comes alive, and together they step into a new reality where imagination, love, and divinity intertwine.

This myth has inspired poets, painters, sculptors, and playwrights for centuries. It resonates because it touches on something profoundly human—the longing for perfection, the belief in transformation, and the power of love to animate the seemingly lifeless. To explore the myth of Pygmalion and Galatea is to enter a story that is at once artistic, psychological, cultural, and deeply philosophical.

The Setting: Cyprus, the Island of Aphrodite

The tale unfolds on Cyprus, an island steeped in myth and famously regarded as the birthplace of Aphrodite, the goddess of love and beauty. Cyprus was no ordinary location in Greek imagination—it was a liminal space between sea and land, a place of sensuality and fertility. To situate the story there is to frame it within the domain of Aphrodite, the very goddess who would later alter the course of Pygmalion’s fate.

The myth first appears in written form through the Roman poet Ovid, in his masterpiece Metamorphoses. Ovid’s work was not just a retelling of myths but an exploration of change—of things becoming other than they were. The myth of Pygmalion is perfectly at home in this context: stone becomes flesh, desire becomes reality, and an artist’s creation becomes a living being.

Pygmalion: The Artist Who Rejected Humanity

Pygmalion, according to the myth, was a talented sculptor. But his story begins not with love, but with rejection. Disgusted by what he perceived as the flaws of mortal women—vanity, corruption, or moral weakness—he withdrew from human companionship. He turned away from relationships altogether and poured his energy into art.

This choice is more than just an individual’s disdain; it reflects a recurring theme in mythology and philosophy: the tension between the imperfect reality of human beings and the desire for an ideal form. Pygmalion’s heart, closed to human affection, sought solace in the purity of ivory and the permanence of his art.

In creating a statue of a woman, Pygmalion was not simply shaping a figure. He was projecting his yearning for perfection, crafting a being that embodied beauty, purity, and grace—qualities he believed absent from real life. And in this act of creation, he unknowingly began to blur the line between art and life, desire and reality.

Galatea: The Woman of Stone

The statue that emerged from Pygmalion’s hands was no ordinary sculpture. It was so exquisitely lifelike that even the gods could have mistaken it for flesh. Every curve, every feature radiated perfection. The statue seemed to breathe, to hold within it the potential of life, though it remained silent and cold to the touch.

Ovid never named this statue in his telling, but later traditions gave her the name Galatea, from the Greek word meaning “she who is milk-white.” The name emphasizes her purity, her ivory glow, and her status as an idealized form of beauty.

What is striking in the story is that Galatea does not exist as an independent being until she is animated by the gods. At first, she is only the mirror of Pygmalion’s desires, the embodiment of an unattainable dream. And yet, when she comes to life, she steps beyond being an object and becomes a subject—one capable of love, choice, and connection.

Love for the Unattainable

It was inevitable that Pygmalion would fall in love with his own creation. He clothed her in fine garments, adorned her with jewelry, and laid her on a couch as if she were alive. He caressed the statue, whispered to it, and kissed its lips, hoping for warmth that never came. He even brought her gifts—shells, beads, flowers, and birds—as if wooing a living woman.

In these actions lies the heart of the myth: the paradox of loving something that is not alive. Pygmalion’s longing was both tragic and tender. He knew she was stone, yet his heart responded as though she were flesh. In this longing, he represented one of humanity’s oldest dreams—that our creations might surpass their lifelessness, that imagination might breathe life into matter.

The Festival of Aphrodite

The turning point of the myth comes with the festival of Aphrodite, the goddess of love. Pygmalion, unable to bear his yearning, prayed at the goddess’s altar. He did not dare ask directly for the statue to be brought to life. Instead, he prayed for a bride as beautiful as his ivory maiden. This humility, this indirect plea, was enough to move Aphrodite’s heart.

The goddess understood not only Pygmalion’s longing but also the depth of his devotion. In response, she performed one of the most beautiful acts of divine intervention in mythology: she brought life to art.

Stone Becomes Flesh

When Pygmalion returned home, he approached his statue as he always did. But this time, something was different. As he kissed her lips, warmth spread beneath his touch. The ivory softened, yielding like flesh. The statue’s chest began to rise and fall with breath. Eyes once fixed in stone opened with living light. Galatea was alive.

This transformation is the core miracle of the myth: love and art together overcoming the barrier between inanimate and animate, between dream and reality. Galatea’s first moment of life is not simply a miracle of the gods but a testament to the power of creation and desire.

The Union of Pygmalion and Galatea

With Galatea alive, Pygmalion’s story moves from longing to fulfillment. The two were united in marriage, and depending on the version of the myth, they even had a child together—Paphos, after whom the city of Paphos in Cyprus was named, and sometimes a daughter named Metharme. Their union symbolized not just personal happiness but also a sacred harmony between art, love, and divine blessing.

Unlike many Greek myths, which end in tragedy, the story of Pygmalion and Galatea concludes with joy. It is rare in mythology for human longing to be so directly rewarded, for desire to be fulfilled without punishment. This rarity may be one reason the story has endured with such tenderness across the centuries.

Artistic and Literary Legacy

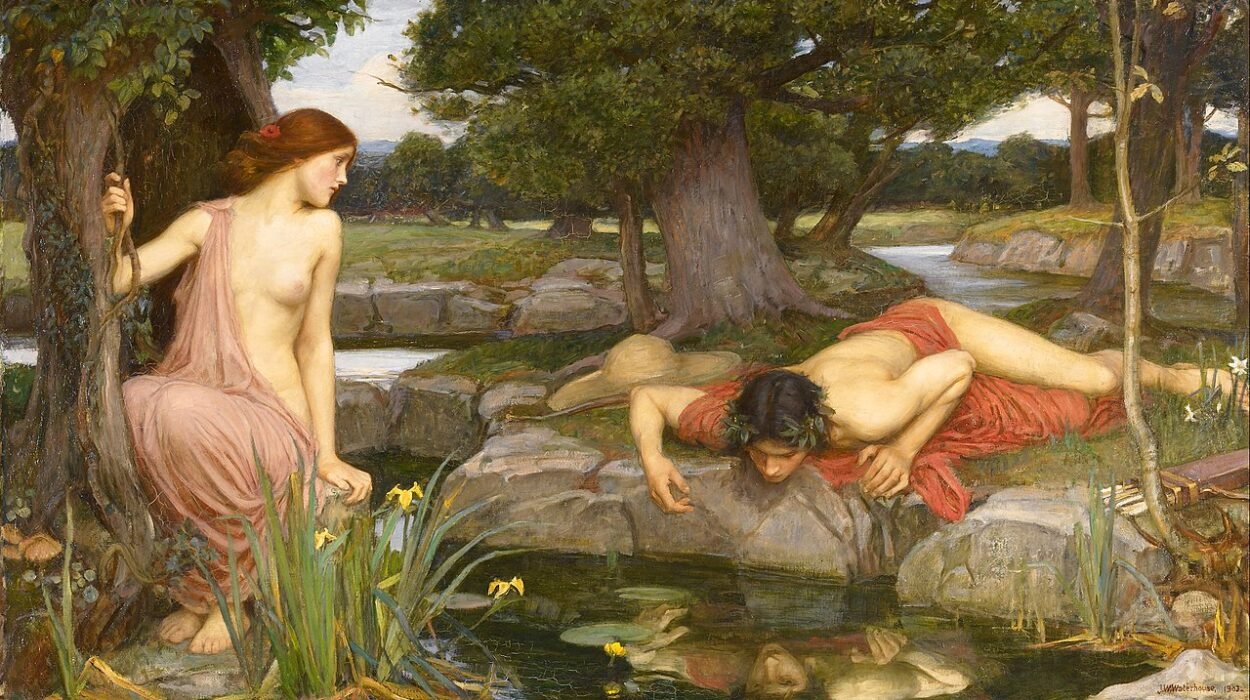

The myth of Pygmalion and Galatea has had an extraordinary afterlife in art, literature, and philosophy. It has been retold and reimagined countless times, each age finding in it new meanings.

In the Renaissance, painters depicted the moment of transformation, capturing the delicate transition from ivory to flesh. In the 18th century, the Irish playwright George Bernard Shaw reinterpreted the myth in his play Pygmalion, where the sculptor becomes a professor of phonetics, and the statue becomes Eliza Doolittle, a working-class woman transformed through language and education. Shaw’s play later inspired the beloved musical My Fair Lady.

In modern times, the myth is often seen as a parable about the relationship between creators and their creations—whether artists and their art, or even scientists and the artificial intelligences they design. It raises questions that are startlingly relevant today: What responsibilities do creators have toward what they bring to life? Where does admiration end and objectification begin? Can love flourish between what is made and what is real?

Psychological Dimensions of the Myth

From a psychological perspective, the story resonates with themes of projection and idealization. Pygmalion could not accept the flaws of real women, so he created an image of perfection. His love was initially not for a person but for his own ideal. In Galatea’s animation, this ideal was given reality.

This dynamic has fascinated psychologists and thinkers for generations. The “Pygmalion effect,” a term in modern psychology, refers to the phenomenon where higher expectations lead to improved performance. Just as Pygmalion’s belief in Galatea’s beauty and worth helped bring her to life, so too can human expectations shape the outcomes of others.

But the myth also serves as a caution: when we love only an ideal, we risk missing the reality of flawed, living beings. Galatea’s gift of life reminds us that perfection is not necessary for love—that love itself can animate and transform.

Symbolism of Transformation

At its core, the story of Pygmalion and Galatea is a story of transformation. Stone becomes flesh, loneliness becomes companionship, art becomes life. Transformation is one of the central motifs of mythology, and here it speaks to humanity’s deepest yearnings.

The myth reminds us that art is never merely static—it has the power to move, inspire, and even change the course of lives. It also reminds us that love has the power to awaken what seems lifeless, to transform despair into joy. In Galatea’s awakening, we see the miracle of potential becoming real, of imagination touching the tangible.

The Myth in the Modern World

Even in our age of technology and science, the myth of Pygmalion and Galatea remains strikingly relevant. It echoes in our fascination with artificial intelligence, robotics, and virtual reality. As humans create machines and simulations ever more lifelike, the old questions return: Can love exist between creator and creation? Where does the boundary between reality and artifice lie?

The myth also continues to inspire artists, writers, and filmmakers who explore the theme of love for the unattainable or the transformation of the ideal into reality. From romantic films to speculative science fiction, the spirit of Pygmalion lives on, reminding us of both the power and the peril of our creative desires.

The Beauty of a Happy Ending

In a world where myths often caution with tragedy—the fall of Icarus, the punishment of Prometheus, the sorrow of Orpheus—the story of Pygmalion and Galatea stands apart as a tale of fulfilled hope. It reassures us that sometimes, longing can be answered, that sometimes the divine smiles upon human yearning.

It is a myth of possibility, of dreams becoming real, of love born from stone. In Pygmalion’s embrace of Galatea, we glimpse the eternal human hope: that love can create life, that beauty can inspire reality, and that the heart’s deepest longing might one day be answered.