Among the haunting images that emerge from ancient Greek mythology, few are as enduring as that of Charon, the ferryman of souls. In the minds of poets, philosophers, and storytellers, he is a figure who waits in silence on the mist-shrouded banks of the River Styx, guiding the dead across to the underworld. Charon is not a god of thunder, nor a ruler of Olympus, nor even a mighty hero celebrated in epics. Yet, his presence resonates deeply because he embodies the mystery that none can escape: the passage from life into death.

When people in ancient Greece thought of what awaited them after their final breath, Charon was there. He was the one who would ferry them from the realm of the living to that of the dead. Neither cruel nor kind, neither savior nor tormentor, Charon was a function of necessity—an eternal boatman whose existence reminds us that death, for all its uncertainty, is inevitable.

To understand Charon is to delve into the Greek vision of the afterlife, a vision filled with rivers, shadows, gates, and rulers beyond mortality. It is to uncover how humans, for millennia, have wrestled with the mystery of what lies beyond the grave, shaping rituals, art, and philosophy around this somber figure.

The Origins of Charon in Myth

The name “Charon” likely comes from the Greek word charopós, which can mean “keen gaze” or “fierce brightness,” perhaps referencing his sharp, piercing eyes. Ancient authors described him as grim, unyielding, and aged. He was not meant to inspire affection but reverence and dread.

Charon’s earliest appearances in Greek literature are fragmentary, surfacing in passages from the 5th century BCE and later solidified in classical works. In Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey, there is no mention of Charon, though the afterlife is described. It was later poets and playwrights—particularly in Athenian tragedy—who gave him form and purpose. By the time of Virgil’s Aeneid in the Roman world, Charon had become an indispensable figure in the mythological geography of death.

He is usually portrayed as a rough, unkempt old man with a weathered cloak and a pole in his hand, steering a simple boat across the underworld’s waters. Unlike the Olympians, he is not adorned with glory. Unlike Hades, he does not rule. His entire being is defined by duty, by the endless ferrying of souls.

The Rivers of the Underworld

To understand Charon’s role, one must step into the Greek conception of the underworld itself. This realm, ruled by Hades and Persephone, was imagined as a vast and shadowy domain beneath the earth, separated from the world of the living by great rivers.

The most famous of these is the River Styx, whose name means “hatred” or “abhorrence.” It is the river of oaths, a boundary no god or mortal could cross without consequence. Yet the Styx is not alone. Ancient texts also describe the Acheron (river of sorrow), the Cocytus (river of wailing), the Phlegethon (river of fire), and the Lethe (river of forgetfulness).

Charon’s ferry was said to cross primarily the Acheron or the Styx, depending on the author. To the Greeks, these rivers were not mere geography but powerful metaphors. They symbolized the emotional states of the dead—the sorrow of departure, the cries of mourning, the fire of punishment, and the oblivion of forgetfulness. And across these waters stood Charon, the mediator between life’s final moment and the eternity that followed.

The Toll of Passage

Charon’s service was never free. To cross the river, the soul of the deceased had to pay him a coin, usually an obol, a small piece of silver or bronze placed in the mouth or upon the eyes of the dead before burial. This practice, known as the “Charon’s obol,” was widespread in Greek funerary tradition and later adopted by the Romans.

The coin was not simply a fare; it was a recognition of the sacred transaction between the living and the dead. Without it, the departed risked being left behind, wandering the banks of the river for a hundred years, never able to rest in the realm beyond.

This belief gave funerary rites profound weight. To fail to bury a loved one properly, or to neglect to provide the coin, was not merely dishonor—it was a denial of peace for the soul. Thus, Charon became not only a ferryman but also a symbol of the importance of ritual, respect, and memory in human culture.

The Unyielding Boatman

Charon is unique among mythological figures in that he is utterly incorruptible. Unlike many gods who may be swayed by prayer, sacrifice, or cunning, Charon demands only his due. He does not discriminate between rich and poor, king and beggar, hero and coward. In death, all are equal passengers.

Poets describe him as silent and grim, rarely speaking to those he ferries. He does not decide their fate—that belongs to Hades, Persephone, and the judges of the underworld. He simply carries them across the waters, his eternal duty unending.

In this, Charon embodies the impartiality of death itself. No plea can sway him, no bribe can deter him. His boat moves steadily, as it has since the beginning of time, and will until its end.

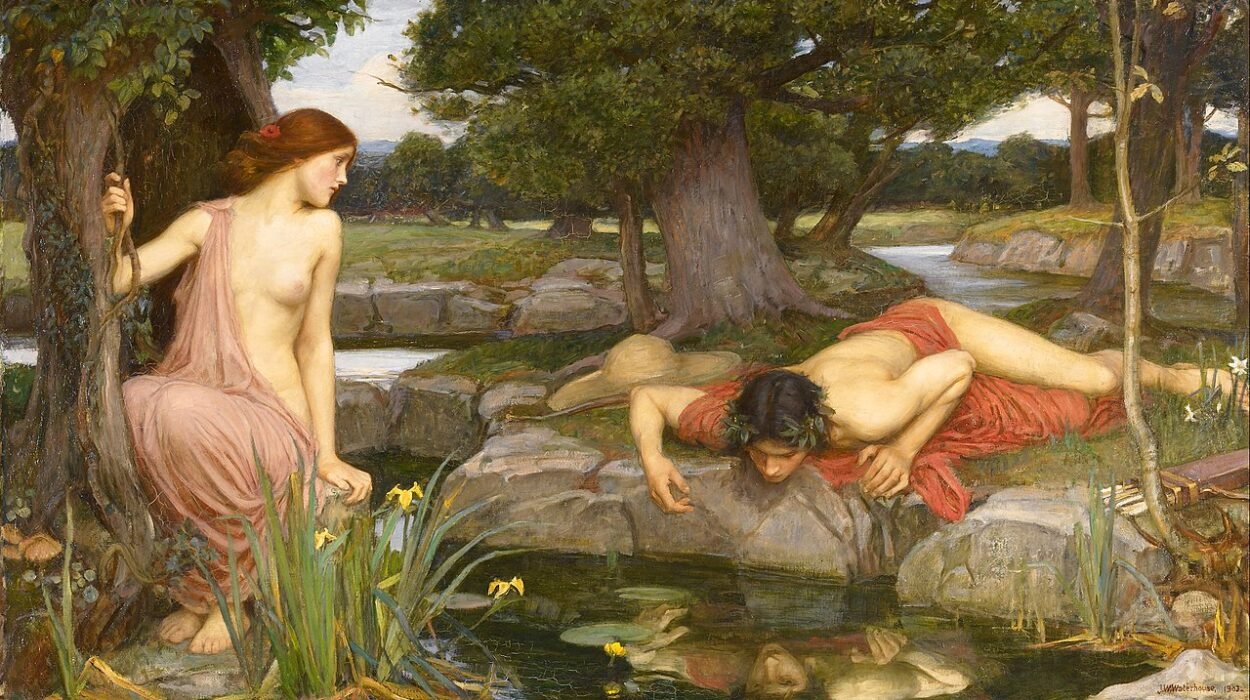

Charon in Literature and Art

The figure of Charon appears across countless works of ancient and later literature. In Virgil’s Aeneid, Aeneas witnesses the ferryman’s terrifying visage: “A sordid god, in filthy garb, his eyes like hollow flame.” Here, Charon is depicted not merely as old but as a supernatural presence, terrifying and majestic in his grim function.

In Dante’s Inferno, centuries later, Charon reappears as the demon boatman of Hell, guiding damned souls across the river Acheron into eternal torment. The poet’s description borrows from Greek myth but recasts Charon into a Christian vision of judgment and punishment.

Greek vase paintings often depicted him as a thin, bearded man, holding an oar and waiting for the soul, usually represented by a small, winged figure. These images reflect how deeply ingrained Charon was in the cultural imagination—not as a myth far removed from daily life, but as a presence tied directly to funeral customs and beliefs about the afterlife.

Philosophical and Cultural Symbolism

Beyond myth and ritual, Charon holds a symbolic place in philosophy and culture. He represents the threshold between existence and nonexistence, a liminal figure who stands at the point of transition. His ferry is a metaphor for the unavoidable journey we all must take, a journey no one else can undertake for us.

To some, Charon also embodies the neutrality of nature. Just as rivers flow without malice or kindness, death comes impartially. Charon’s indifference echoes this truth. His task is not moral judgment but simple passage, much like the natural processes that carry us from birth to death.

In modern psychology and literature, Charon has been interpreted as the guide of transformation, not only in death but in life’s symbolic transitions. Crossing his river can symbolize leaving behind an old self, a past, or an identity, stepping into something unknown.

Charon in Roman and Later Traditions

The Romans, inheriting much of Greek mythology, embraced Charon in their own funerary customs. Roman coins have been discovered in graves across the empire, placed with the deceased for their journey. Writers such as Ovid and Virgil gave Charon vivid description, cementing his place in Western imagination.

Later, in medieval Europe, Charon’s figure fused with Christian notions of judgment and the soul’s journey after death. Though not part of Christian doctrine, he appears in art and poetry as a symbol of passage to the afterlife, a reminder of mortality’s universality.

Even today, Charon’s image lingers in literature, music, and popular culture. From operas to fantasy novels, from paintings to video games, the ferryman continues to haunt humanity’s imagination. His boat still sails in our collective dreams, carrying souls across the shadowed waters of death.

The Psychological Impact of Charon

Charon resonates because he personifies what is most feared and most inevitable. He is not a punisher like the Furies, nor a judge like Minos, but simply a presence we cannot avoid. In him, humanity projects its deepest confrontation with mortality.

He strips away illusions of control. No matter how mighty, how wealthy, or how wise, every mortal will someday face the ferryman. In this sense, Charon provides not only fear but also a strange equality—a reminder that death unites all humans beyond the divisions of life.

Psychologists and philosophers have suggested that such mythological figures provide a way for humans to process the incomprehensible. By giving death a face—a ferryman with an oar—ancient Greeks made the unimaginable journey into something more tangible, something that could be honored, feared, and prepared for.

Charon in the Modern Imagination

Though the age of Greek temples and Roman forums has long passed, Charon still lingers. His name is given to one of Pluto’s moons, discovered in 1978—a fitting celestial homage, as Pluto itself is the Roman name for Hades. In this way, astronomy pays tribute to mythology, linking the farthest reaches of space to humanity’s oldest fears and stories.

In literature and art, Charon remains a symbol of passage. Writers use him as a metaphor for endings and beginnings, artists paint him as the eternal boatman, and musicians evoke his name in songs of mortality. Even in films and video games, where mythological figures often return, Charon appears as the somber guide through shadowed realms.

His endurance proves the power of myth to transcend time. While gods of war and heroes of battle fade with changing cultures, the ferryman of souls remains, because his truth is universal. Death waits for all, and Charon is its symbol.

The Ferryman’s Eternal Lesson

Charon is not a god who grants blessings or punishes sins. He is not a hero who rescues or conquers. His power lies in his simplicity: the endless ferry across the waters of death. In him, the Greeks crystallized the mystery of mortality into a vivid image that still speaks to us today.

He teaches that rituals matter—that how we honor the dead reflects how we value life. He teaches that death is impartial, beyond wealth, power, or pride. And he teaches that the journey beyond life is not one of escape but of acceptance, a transition we all must face.

Standing in the ancient imagination, pole in hand, eyes fierce and unyielding, Charon is the guardian of the final threshold. To speak of him is to confront our own mortality, to gaze into the waters that await us all.

And yet, in that gaze, there is not only fear but also recognition. For Charon’s ferry is not only about endings. It is also about the continuity of humanity’s search for meaning, the rituals that bind us across generations, and the enduring need to tell stories about life, death, and what lies beyond.

In his silence, Charon reminds us that death is not an enemy but a passage. And though we may not know what waits on the far shore, the image of the ferryman assures us that the journey itself is shared by all who have ever lived and all who ever will.