On the sun-drenched island of Crete, where the Aegean Sea meets the mountains, there lingers a tale as ancient as civilization itself—a story of kings and monsters, of gods and mortals, of human ingenuity and divine wrath. It is the legend of the Labyrinth, a maze so vast and so cunningly built that none who entered could ever find their way out. At its center lurked the Minotaur, a creature of both man and bull, born of passion, punishment, and fate.

The tale of the Labyrinth of Crete is more than just a story told by poets and playwrights. It is a cultural monument, a piece of human imagination that has echoed through time, shaping art, literature, and even archaeology. But it is also a mystery: was there truly a Labyrinth hidden beneath the palaces of ancient Crete, or does the story reflect something deeper—a symbolic maze of human fears, desires, and the struggle for power?

To walk through the myth of the Labyrinth is to journey not only into the heart of Greek mythology but also into the ancient world’s attempts to understand order and chaos, civilization and savagery, life and death.

The Birth of a Monster

The Labyrinth’s most famous inhabitant was the Minotaur, a being who embodied both terror and tragedy. The story begins with King Minos of Crete, a figure whose ambition and cunning were matched only by his defiance of the gods.

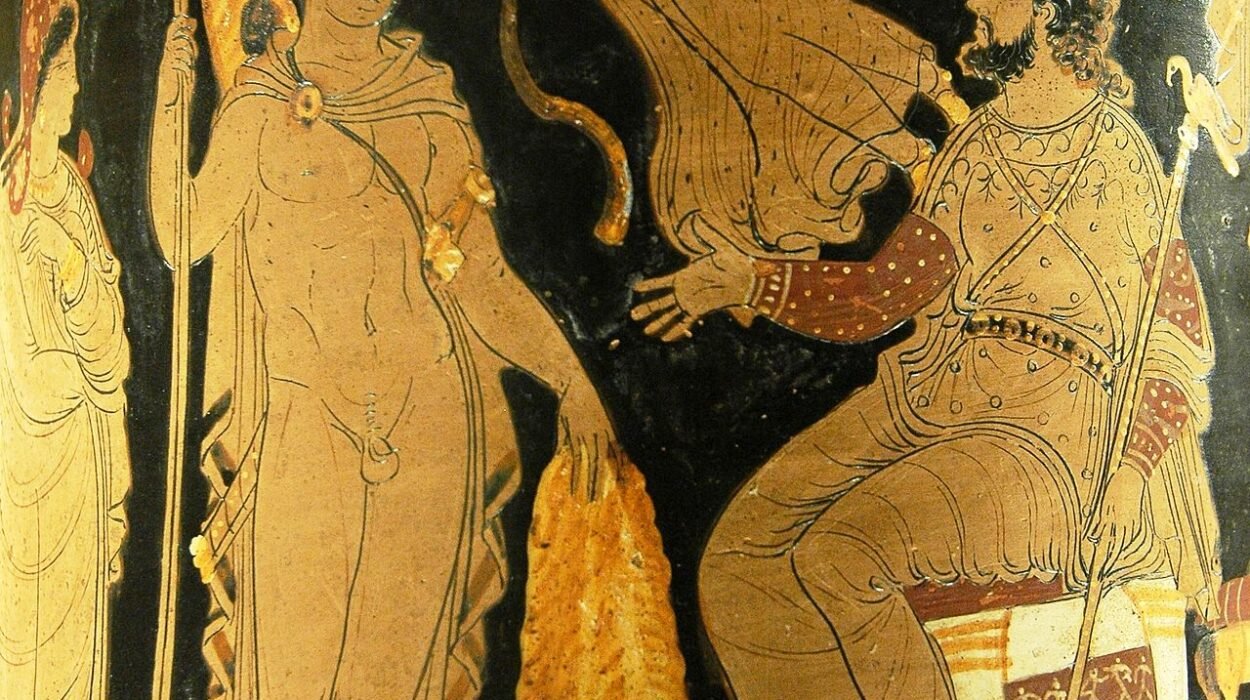

Minos, according to myth, once prayed to the sea-god Poseidon to send him a sign of his right to rule. From the depths of the ocean, Poseidon sent forth a magnificent white bull. It was to be sacrificed in honor of the god, but when Minos beheld its beauty, he could not bring himself to kill it. Instead, he kept the bull for himself and offered an inferior animal in its place.

This act of arrogance enraged Poseidon, who devised a punishment as cruel as it was unforgettable. He caused Minos’s wife, Queen Pasiphaë, to fall in unnatural love with the bull. From this union was born the Minotaur—half man, half bull, a creature neither fully human nor fully beast.

The Minotaur was a living shame to Minos, a monstrous reminder of his defiance. Unable to kill the creature yet unwilling to expose his disgrace, Minos turned to one of the most brilliant minds of the ancient world: Daedalus, the master craftsman.

The Labyrinth: Architecture of the Impossible

Daedalus was no ordinary builder. In myth, he was a genius whose inventions bordered on the divine. To contain the Minotaur, he designed the Labyrinth, a structure so intricate and complex that it defied comprehension.

Descriptions of the Labyrinth vary, but all emphasize its unfathomable nature. Some imagined it as a maze of endless corridors, twisting back upon themselves, doors that led nowhere, and passages that deceived the senses. Others pictured it as an underground fortress, a hidden prison buried beneath the palace of Knossos, where light could barely penetrate and escape was impossible.

The symbolism of the Labyrinth was as powerful as its physical description. It was not merely a building but a metaphor for entrapment, confusion, and the human condition itself. To enter the Labyrinth was to lose oneself in the very architecture of despair.

Modern scholars and archaeologists have often connected the myth of the Labyrinth with the ruins of the Minoan palace at Knossos. Excavated by Sir Arthur Evans in the early 20th century, Knossos revealed a sprawling, multi-leveled complex with countless rooms, stairways, and corridors. To ancient eyes, such a place could indeed seem like a Labyrinth. Whether or not the Minotaur dwelled there, the palace itself was a marvel of Bronze Age architecture and organization.

Tribute of Blood: The Price of Peace

The story of the Labyrinth does not end with the building or even the beast. It also tells of the heavy toll it took upon human lives. According to myth, Athens was once at war with Crete. After their defeat, the Athenians were forced to pay tribute to King Minos: every nine years, they were to send seven young men and seven young women to Crete as sacrifices. These youths were led into the Labyrinth, where the Minotaur devoured them, and none ever returned.

This tribute became a symbol of tyranny and fear, a reminder of Athens’s submission to Crete’s power. It also set the stage for the arrival of one of Greece’s greatest heroes, Theseus.

Theseus and the Slaying of the Beast

Into this tale of suffering stepped Theseus, prince of Athens, whose courage would forever change the story of the Labyrinth. Determined to end the cycle of death, Theseus volunteered to be among the youths sent to Crete. His goal was not only survival but also the destruction of the Minotaur itself.

Upon his arrival, fate brought him into the path of Ariadne, the daughter of King Minos. Struck by love—or perhaps by pity—Ariadne resolved to help him. She gave him a ball of thread, a simple yet brilliant solution to the Labyrinth’s impossible complexity. Theseus would tie one end at the entrance and unravel it as he went deeper, ensuring that he could always find his way back.

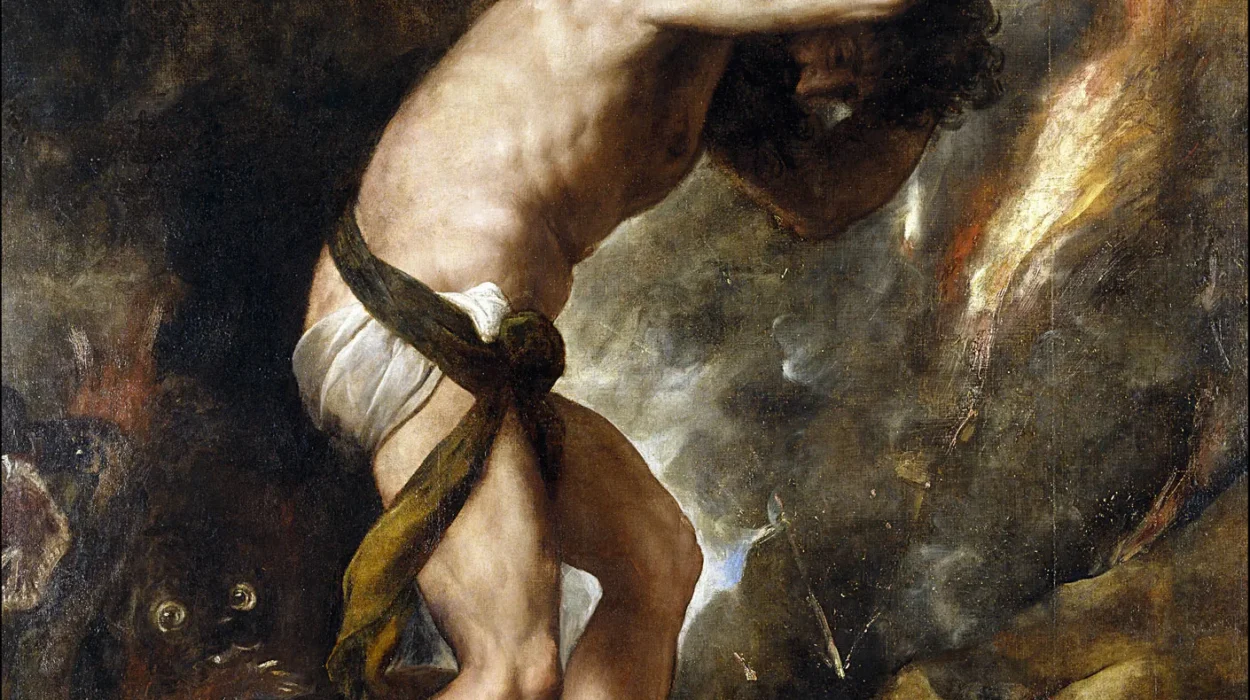

Guided by Ariadne’s thread, Theseus ventured into the heart of the Labyrinth. There he encountered the Minotaur, and in a brutal struggle, he slew the creature with his bare hands or, in some versions, with a sword given to him by Ariadne. Emerging victorious, Theseus led the surviving Athenians out of the maze, following the path he had marked with the thread.

This act of bravery ended the reign of terror and became one of the foundational legends of Athens—a city that valued freedom, cunning, and heroism above all.

The Symbolism of the Labyrinth

The story of the Labyrinth is not merely about walls and monsters. It is a tale thick with symbolism, which is why it has survived for thousands of years.

The Minotaur represents the dark consequences of human pride and divine punishment. Born of lust and deception, it is a reminder that the sins of rulers can create monsters that haunt entire nations.

The Labyrinth itself symbolizes the complexity of life, the confusion of the human mind, and the traps of fate. To be lost in the Labyrinth is to be lost in existence, wandering without direction.

Theseus, with his courage and Ariadne’s thread, represents the triumph of intellect and bravery over chaos. The thread is not only a physical guide but also a symbol of love, trust, and human ingenuity. It reminds us that even in the darkest maze, there is a way forward if we hold on to wisdom and connection.

Knossos and the Archaeological Labyrinth

For centuries, the Labyrinth was thought to be purely mythical. Yet when Arthur Evans unearthed the palace of Knossos in Crete at the start of the 20th century, many began to wonder if myth and reality were intertwined.

Knossos was not a simple palace—it was a vast, sprawling complex with over a thousand rooms, intricate stairways, storage chambers, workshops, and ceremonial spaces. Its frescoes depicted bulls, athletes leaping over them, and symbols that could easily have inspired the legends of the Minotaur.

To an ancient visitor, Knossos may indeed have seemed like a Labyrinth, a place where one could easily lose one’s way. The “double axe,” or labrys, a sacred symbol found throughout the palace, may even be the origin of the very word “Labyrinth.”

While no physical evidence of a literal underground maze has been found, the palace itself provides a powerful backdrop to the myth. It shows how reality and imagination can blend, how a complex building could inspire a story of a prison for monsters.

The Labyrinth Across Cultures

The myth of the Labyrinth is uniquely Greek, yet its themes resonate across cultures. The idea of a maze as a symbol of life, death, and spiritual journey appears in many traditions.

In Egypt, temples with winding passages were designed to mirror the mysteries of the afterlife. In medieval Europe, labyrinths were built into cathedral floors, not as prisons but as paths for meditation and spiritual reflection. The labyrinth became a symbol of pilgrimage, of moving toward the center of truth.

Even today, labyrinths are created in gardens, parks, and spiritual retreats as places of contemplation. They remind us that the journey inward is as important as the journey outward, that sometimes to find clarity we must first walk through confusion.

The Enduring Power of the Myth

Why has the story of the Labyrinth endured for so long? Perhaps because it touches something eternal in the human soul. We all face monsters of our own—fears, doubts, challenges—that seem impossible to overcome. We all wander through labyrinths of uncertainty, searching for a path. And we all long for a thread, a guide, a glimmer of hope to lead us out.

The Labyrinth of Crete is more than a myth about a king and a beast. It is a mirror of humanity’s struggles: our pride, our punishments, our courage, and our capacity for love and ingenuity.

Even now, thousands of years after Theseus supposedly walked its halls, the Labyrinth remains alive—in literature, in psychology, in architecture, and in the very way we speak of confusion and clarity. It is not just a story of the past but a story of the human condition itself.

Walking the Labyrinth Today

To stand among the ruins of Knossos today is to feel the weight of both history and myth. The crumbling stones, the reconstructed frescoes, the silent corridors—all seem to whisper of a time when gods and humans mingled, when myths were born from stone and sea.

For visitors, the palace is both an archaeological site and a mythical pilgrimage. One can imagine the roar of the Minotaur echoing through its walls, the bravery of Theseus as he tightened his grip on the thread, the sorrow of Ariadne left behind on the shores of Naxos after her betrayal.

The Labyrinth may not exist in stone as the ancients described it, but it exists in our minds. It is a place we still walk, in stories and in spirit, each time we face the unknown.

Conclusion: The Eternal Maze

The Labyrinth of Crete is one of humanity’s greatest legends, a story that fuses architecture, mythology, psychology, and philosophy. It is a tale of punishment and redemption, of chaos and order, of monsters and heroes.

Whether or not the Minotaur ever lived, whether or not a literal maze lay beneath Knossos, the Labyrinth is real. It lives in the questions we ask, the challenges we face, and the journeys we take to find meaning in our lives.

In the end, we are all Theseus. We all step into the maze. And though the walls may seem endless, though the Minotaur may seem unstoppable, there is always a thread—a thread of courage, of love, of wisdom—that can lead us home.