For thousands of years, the legendary city of Troy has captured the imagination of poets, archaeologists, and dreamers. Immortalized in Homer’s Iliad as a city of heroes, gods, and war, Troy was a place where men fought and gods feasted. While Homer’s verses speak of divine banquets and shared goblets of nectar, the line between myth and reality has often been elusive. Now, a groundbreaking scientific discovery has shifted that boundary.

For the first time in recorded history, researchers have uncovered chemical evidence confirming that wine—real, fermented grape wine—was indeed consumed in ancient Troy. This discovery, announced in the April edition of the American Journal of Archaeology, provides stunning validation of a long-standing hypothesis proposed by Heinrich Schliemann, the 19th-century archaeologist who unearthed the ruins of Troy.

But this is no ordinary archaeological milestone. The findings do more than confirm Schliemann’s century-old conjecture; they open a new window into the daily lives of both the ruling elite and the common people of Bronze Age Troy. They transform a poetic vision into a scientific reality.

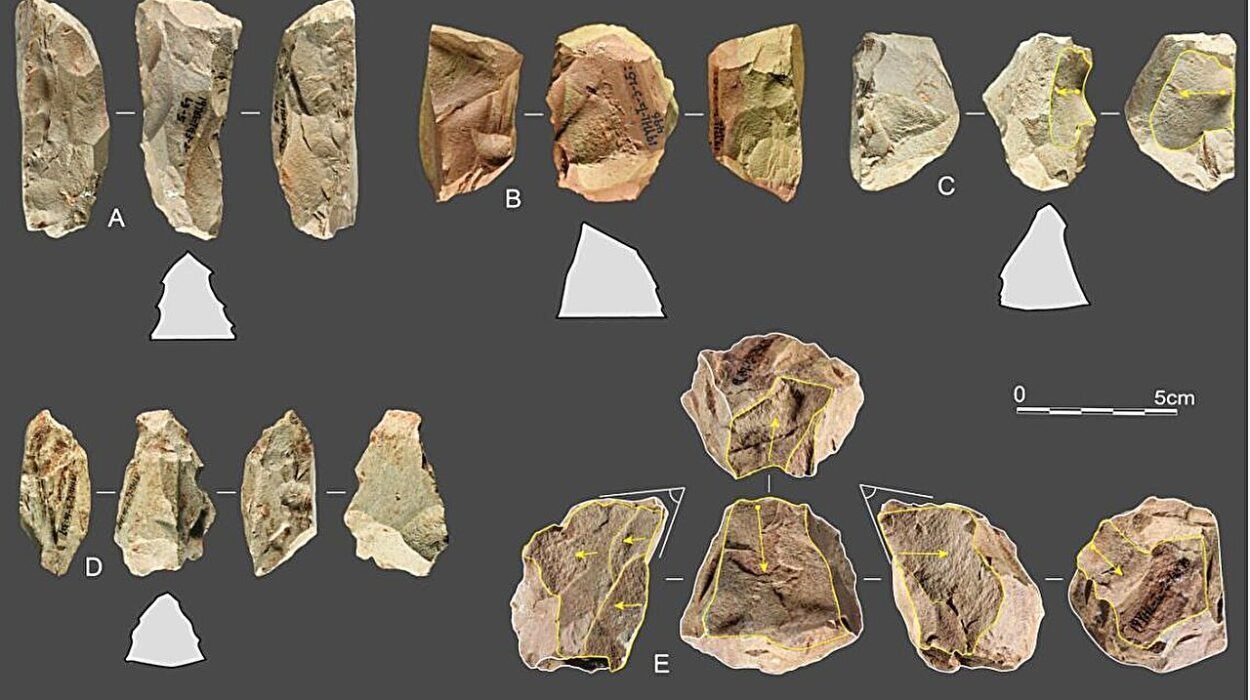

The key to this revelation is a humble yet iconic object: the depas amphikypellon, or depas goblet. Often described in Homeric poetry, this distinctive vessel—with its two handles and pointed base—has become an emblem of the ancient Aegean world. More than 100 of these goblets have been discovered at the Troy excavation site, dating back to between 2500 and 2000 BCE. Yet until now, no one could say with certainty what they were used for. Were they symbolic? Ceremonial? Or were they, as Schliemann believed, the very cups from which ancient Trojans drank their wine?

The answer has now been delivered not by myth, but by science.

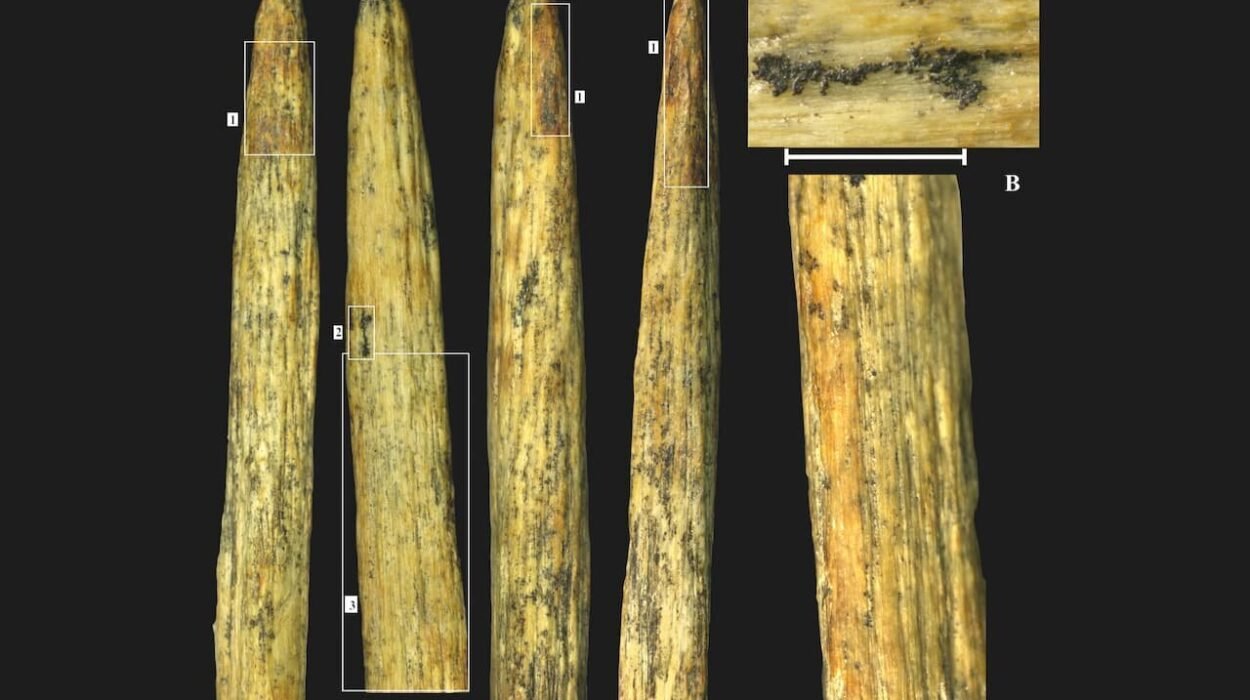

The classical archaeology collection at the University of Tübingen holds a pristine depas goblet and two fragments excavated from the site of ancient Troy. Researchers led by Dr. Stephan Blum from the University of Tübingen and Maxime Rageot from the University of Bonn performed a chemical analysis on these artifacts. The process involved milling a tiny, two-gram sample from the ceramic fragments, then subjecting the material to high temperatures and analysis through gas chromatography (GC) and mass spectrometry (GC-MS).

The results were unequivocal. The researchers detected the presence of succinic and pyruvic acids—compounds that are only produced when grape juice undergoes fermentation. This is chemical proof, beyond any reasonable doubt, that the vessels were used to hold wine. Not just grape juice. Not a symbolic libation. Real, alcoholic wine.

“Now we can state with confidence that wine was actually drunk from the depas goblets,” said Rageot. “This isn’t mere speculation or poetic embellishment—it’s a molecular fingerprint of fermentation left behind thousands of years ago.”

This revelation elevates the depas goblet from an archaeological curiosity to a vessel of historical truth. In Homer’s Iliad, gods drink from shared cups in moments of camaraderie and celebration. In real life, these same cups held a potent liquid that flowed through the veins of Troy’s vibrant society.

Wine in the Bronze Age was more than a beverage. It was both a luxury and a symbol of status. Its production required intensive labor, storage facilities, and control over agricultural resources. For many years, scholars assumed that only Troy’s aristocracy had access to such a costly and refined product. Depas goblets, often found in palaces and temples, seemed to support this narrative. Yet the latest research reveals a far more inclusive reality.

Blum and his team extended their analysis beyond elite artifacts. They sampled ordinary cups excavated from Troy’s outer settlement—regions far outside the city’s citadel, where the lower classes lived and worked. Astonishingly, they discovered the same chemical markers of fermented grape wine.

This means that wine consumption in ancient Troy was not confined to the royal court or high temple. It was a part of everyday life, enjoyed by merchants, farmers, and laborers alike. The wine may have varied in quality or preparation, but the act of drinking it crossed social boundaries.

“So it is clear,” says Blum, “that wine was an everyday drink for the common people too.”

This finding carries profound implications for our understanding of Bronze Age Troy. It tells us that wine culture was not just about elite ceremonies—it was part of a shared communal experience, a bridge between classes, and perhaps a vital ingredient in forging social cohesion in a complex urban society.

It also reaffirms the literary insight of the ancients. Homer’s epics, while mythological, were grounded in cultural practices that reflected the real world. In the Iliad, the scene of Hephaestus offering his mother a double-handled goblet and pouring nectar for the gods is no longer just metaphor. It is a vivid echo of an actual custom.

The implications ripple outward. The depas goblet is not unique to Troy. It has been found across the Aegean, Asia Minor, and even Mesopotamia. This shared vessel design hints at trade networks, cultural exchange, and a widespread tradition of wine drinking across early Mediterranean civilizations.

Wine, after all, is a connector. It requires not just grapes, but pottery, preservation methods, and skilled fermentation. The knowledge and tools for producing it had to travel, spreading through merchant routes and migration paths. The discovery at Troy confirms that this fermented knowledge had taken root on the northwestern edge of Asia Minor, a place where East met West and myth met history.

Professor Dr. Karla Pollmann, President of the University of Tübingen, reflected on the significance of the discovery: “Research into Troy has a long tradition at the University of Tübingen, and I am delighted that we have been able to add another piece to the puzzle revealing the picture of Troy.”

That picture is becoming clearer and more vivid with each new discovery. From the early excavations led by Schliemann, whose passionate but controversial methods first revealed the walls of the fabled city, to the modern-day chemical sleuthing of scientists like Rageot and Blum, Troy has never ceased to inspire.

The site of Hisarlık, as it is known in modern-day Turkey, has seen over a century of digs, debates, and reconstructions. Excavations led by the University of Tübingen from 1987 to 2012 have amassed a treasure trove of artifacts. These include not just depas goblets but everyday tools, jewelry, weapons, and building remnants that sketch the outlines of a real society behind the legend.

As these findings are analyzed and reinterpreted with new technology, old questions are being answered—and new ones raised. What did their wine taste like? Was it spiced or diluted, as in other ancient cultures? Did it play a role in rituals, diplomacy, or medicine? Could the remnants of yeast or plant DNA yield even deeper secrets about ancient viniculture?

The answers may yet lie hidden in the microscopic residues of ancient vessels, waiting for the right instruments—and the right questions.

But for now, one truth stands firm. The people of Troy, both high and humble, raised their cups and drank from them. Wine coursed through the heart of their city, as much a part of their story as their walls, their wars, and their heroes.

It’s a story not just of chemistry or archaeology, but of humanity—a shared ritual reaching across time, from the Bronze Age to our own. And with each drop of evidence, the past becomes less a distant myth and more a living memory.

More information: Stephan W.E. Blum et al, The Question of Wine Consumption in Early Bronze Age Troy: Organic Residue Analysis and the Depas amphikypellon, American Journal of Archaeology (2025). DOI: 10.1086/734061