Qin Shi Huang (259-210 BCE), born Ying Zheng, was the first Emperor of China and the founder of the Qin Dynasty. Ascending to the throne at a young age, he unified the warring states of China in 221 BCE, ending centuries of conflict and laying the foundation for the first centralized imperial state. His reign is noted for sweeping reforms, including the standardization of weights, measures, and writing systems, which helped to consolidate his power and unify the diverse regions of China. Qin Shi Huang is also famous for commissioning the construction of the Great Wall of China and the Terracotta Army, which was buried with him to protect him in the afterlife. His rule, though marked by significant achievements, was also characterized by harsh legalist policies and severe repression. Despite his controversial legacy, Qin Shi Huang’s impact on Chinese history and culture remains profound.

Early Life and Ascension to Power

Qin Shi Huang, born as Ying Zheng in 259 BCE, was the son of King Zhuangxiang of Qin and Lady Zhao. His early life was marked by turmoil, as the state of Qin, one of the seven warring states during the late Eastern Zhou Dynasty, was engaged in constant conflict with its neighbors. Ying Zheng’s birth came at a time when the state of Qin was gaining power and influence under the leadership of his father, King Zhuangxiang. However, Ying Zheng’s childhood was complicated by the political machinations of the time, particularly the influence of Lü Buwei, a powerful merchant who played a crucial role in placing King Zhuangxiang on the throne.

At the age of 13, Ying Zheng ascended to the throne following the death of his father in 246 BCE, becoming King of Qin. Due to his youth, Lü Buwei initially served as the regent, effectively controlling the state’s affairs. During these early years, Ying Zheng was exposed to the complexities of governance and the strategies necessary to maintain and expand power. His upbringing was characterized by a mix of intense education, mentorship, and exposure to the harsh realities of political life.

As Ying Zheng grew older, he began to assert his authority, gradually reducing Lü Buwei’s influence. By 238 BCE, at the age of 21, Ying Zheng took full control of the Qin state. His early experiences of political intrigue and warfare shaped his ambition to not only strengthen Qin but to unify the entire Chinese realm under one rule. This ambition set the stage for his future conquests and the eventual establishment of the Qin Dynasty, with Ying Zheng taking on the title of Qin Shi Huang, the First Emperor of China.

The Unification of China

Qin Shi Huang’s reign is most notably marked by his successful unification of China, an achievement that brought an end to the Warring States period, which had seen centuries of conflict among various regional powers. Between 230 BCE and 221 BCE, Qin Shi Huang embarked on a series of military campaigns aimed at conquering the remaining six warring states: Han, Zhao, Wei, Chu, Yan, and Qi. These campaigns were characterized by Qin’s superior military strategies, technological advancements, and the ruthless efficiency of its armies.

The state of Qin had long been preparing for these conquests, building a highly disciplined and well-equipped army. Under the leadership of generals such as Wang Jian and Meng Tian, Qin forces systematically defeated their rivals. The conquest began with the state of Han in 230 BCE, followed by Zhao in 228 BCE, Wei in 225 BCE, and Chu in 223 BCE, each falling in swift succession. The state of Yan was conquered in 222 BCE, and finally, Qi, the last remaining state, was subdued in 221 BCE.

With the unification of China, Qin Shi Huang declared himself the First Emperor, abandoning the title of king. He believed that his accomplishment was so grand that it required a new title, one that would reflect his unprecedented achievement. As Qin Shi Huang, he ruled over a unified China, marking the beginning of the Qin Dynasty. His unification of China was not just a military achievement; it also involved the integration of diverse cultures, languages, and legal systems under a centralized imperial rule. This unification laid the foundation for a centralized state that would influence the development of Chinese civilization for centuries to come.

Administrative Reforms and Centralization

After the unification of China, Qin Shi Huang implemented a series of administrative reforms aimed at centralizing power and standardizing various aspects of governance across the vast empire. These reforms were crucial in establishing the authority of the central government and ensuring the stability and longevity of the newly unified state. One of the most significant reforms was the division of the empire into administrative units known as commanderies and counties. This system replaced the feudal system that had been prevalent during the Warring States period, where local lords held significant power. By appointing loyal officials to govern these regions, Qin Shi Huang ensured that all authority emanated from the central government, thereby reducing the power of the local nobility.

Qin Shi Huang also implemented a series of legal reforms, most notably the standardization of laws across the empire. The legal code was strict and heavily influenced by Legalist principles, which emphasized the importance of law and order in maintaining state control. Harsh punishments were prescribed for even minor offenses, creating a society where fear of retribution ensured compliance with the law. While these laws were often criticized for their severity, they were effective in maintaining social order and reducing dissent within the empire.

Another significant reform was the standardization of weights, measures, and currency. This reform was essential in facilitating trade and commerce across the diverse regions of the empire, as it eliminated the confusion and inefficiencies caused by regional variations. The introduction of a standardized currency, the banliang coin, allowed for more efficient taxation and economic management. In addition to these economic reforms, Qin Shi Huang also standardized the Chinese script, which helped unify the various dialects and languages spoken across the empire. The standardized script allowed for more effective communication and record-keeping, further solidifying the central authority of the Qin government.

Cultural and Intellectual Repression

While Qin Shi Huang is often praised for his achievements in unification and administrative reform, his reign is also marked by cultural and intellectual repression. One of the most infamous events of his reign was the Burning of Books and Burying of Scholars in 213–212 BCE. Concerned with maintaining control over his empire, Qin Shi Huang viewed the diverse schools of thought that had flourished during the earlier Zhou Dynasty as potential threats to his authority. In particular, he saw Confucianism and other philosophies that emphasized morality and the role of the nobleman as challenges to the Legalist principles that underpinned his rule.

To eliminate these potential threats, Qin Shi Huang ordered the burning of books that were deemed subversive or irrelevant to the state. These included works of philosophy, history, and literature that did not align with the state’s ideology. This act of cultural repression was intended to consolidate power by ensuring that only state-approved ideas and values were disseminated throughout the empire. The burning of books was accompanied by the persecution of scholars who were critical of the regime or who adhered to non-Legalist philosophies. Many Confucian scholars were executed or forced into exile, creating an atmosphere of fear and intellectual conformity.

This repression had a profound impact on Chinese culture and intellectual life. The loss of numerous texts meant that much of the knowledge and wisdom of earlier periods was either destroyed or suppressed, leading to a significant cultural decline during the Qin Dynasty. However, it is important to note that while Qin Shi Huang’s policies were repressive, they were also effective in eliminating dissent and consolidating the central authority of the emperor. These actions reflect the duality of Qin Shi Huang’s legacy: while he was a visionary leader who achieved great things, his methods were often harsh and authoritarian.

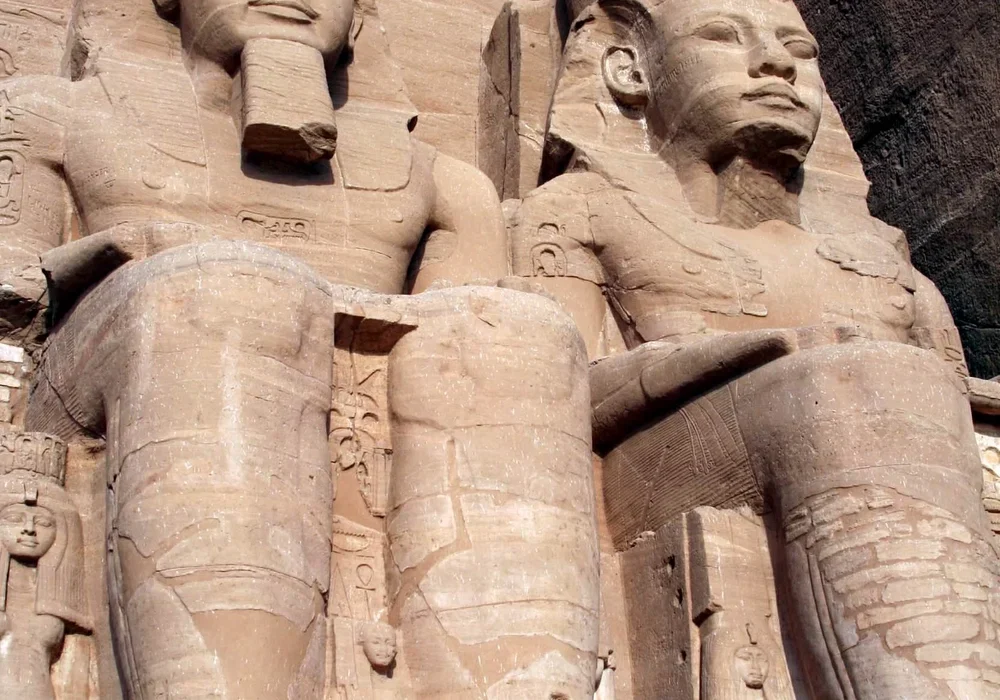

Construction Projects and the Great Wall

Qin Shi Huang is also renowned for his ambitious construction projects, which were aimed at strengthening the empire’s defenses, showcasing its power, and ensuring the emperor’s legacy. One of the most famous of these projects was the construction of the Great Wall of China. The wall was built to protect the northern borders of the empire from invasions by nomadic tribes, particularly the Xiongnu. The construction of the Great Wall was an enormous undertaking, involving the labor of hundreds of thousands of workers. It is estimated that the wall extended over 5,000 kilometers, making it one of the largest construction projects in history.

The Great Wall was not a single, continuous structure but rather a series of walls and fortifications connected by watchtowers and military garrisons. It was built using a combination of rammed earth, wood, and stone, depending on the availability of materials in different regions. The wall served as both a physical barrier and a symbol of the might and determination of the Qin Dynasty. While the Great Wall was not entirely successful in preventing invasions, it did serve as a deterrent and provided a sense of security for the empire’s northern frontier.

In addition to the Great Wall, Qin Shi Huang commissioned the construction of an elaborate mausoleum for himself, which included the famous Terracotta Army. This vast burial complex, located near the modern city of Xi’an, was designed to protect the emperor in the afterlife. The Terracotta Army consists of thousands of life-sized statues of soldiers, horses, and chariots, each individually crafted with unique features. The scale and complexity of the mausoleum reflect Qin Shi Huang’s desire for immortality and his belief in the importance of securing his legacy for eternity.

The construction of these monumental projects came at a great cost. The heavy demands for labor and resources placed a significant burden on the population, leading to widespread suffering and resentment. Many workers died during the construction of the Great Wall and the emperor’s mausoleum, leading to unrest and discontent among the people. Despite these hardships, these projects have left an enduring legacy, with the Great Wall and the Terracotta Army becoming symbols of China’s ancient history and cultural heritage.

Foreign Relations and Military Campaigns

During his reign, Qin Shi Huang also focused on expanding the empire’s influence and securing its borders through military campaigns and diplomatic efforts. The emperor sought to establish Qin as the dominant power in East Asia, pursuing a policy of both aggressive expansion and strategic alliances. One of the key regions of interest was the southern territories, which included areas that are now part of modern-day Guangdong, Guangxi, and Vietnam. These regions were inhabited by various non-Han Chinese peoples, and their incorporation into the Qin Empire was achieved through a combination of military conquest and colonization.

In 214 BCE, Qin Shi Huang launched a series of military campaigns to expand the empire’s control over these southern territories. The campaigns were led by General Zhao Tuo, who successfully conquered the region and established the commanderies of Nanhai, Guilin, and Xiang. These newly acquired territories were integrated into the Qin administrative system, with settlers from the north being encouraged to migrate to these areas to solidify Qin’s control. This expansion not only increased the empire’s territorial reach but also facilitated the spread of Han culture and political influence into the southern regions, laying the groundwork for future Chinese dominance in these areas.

Qin Shi Huang’s foreign policy also involved efforts to secure the empire’s western and northern borders. The emperor pursued a combination of military action and diplomatic negotiations to neutralize threats from nomadic tribes and neighboring states. One of the key challenges came from the Xiongnu, a confederation of nomadic tribes who posed a significant threat to the northern frontier. To counter this threat, Qin Shi Huang ordered the construction of the Great Wall, as previously mentioned, and launched several military campaigns to push the Xiongnu back.

In addition to these defensive measures, Qin Shi Huang also sought to establish diplomatic relations with distant states and peoples. There are records of envoys being sent to the Yuezhi and other tribes in Central Asia, indicating an early attempt to engage in diplomacy and perhaps even trade with the broader region. These efforts, however, were largely limited by the vast distances and the challenges of maintaining long-term relations with distant states. Nonetheless, they demonstrate Qin Shi Huang’s awareness of the wider world beyond China and his desire to secure the empire’s position within it.

Qin Shi Huang’s military campaigns and foreign policy efforts were driven by his desire to protect and expand the empire. While successful in many respects, these endeavors also placed a significant strain on the state’s resources and the population. The continuous demand for soldiers, laborers, and supplies to support the emperor’s ambitions led to widespread exhaustion and dissatisfaction among the people, contributing to the instability that would later emerge after Qin Shi Huang’s death.

Quest for Immortality

As Qin Shi Huang grew older, his fear of death and desire for immortality became increasingly pronounced. The emperor was deeply influenced by traditional Chinese beliefs in the afterlife and the possibility of achieving immortality. This obsession drove him to seek out methods and elixirs that would grant him eternal life, leading to one of the most fascinating and tragic aspects of his reign.

Qin Shi Huang consulted numerous alchemists, magicians, and physicians, offering vast rewards to anyone who could provide him with a formula for immortality. These efforts were not only based on superstition but were also influenced by the Taoist belief in the possibility of achieving immortality through the consumption of certain minerals and compounds. The emperor was known to have consumed various concoctions, including mercury-based elixirs, which were believed to prolong life.

In addition to seeking physical immortality, Qin Shi Huang also embarked on expeditions to locate the legendary islands of the immortals, known as Penglai. He dispatched envoys and ships to search for these mythical lands, hoping to discover the secret to eternal life. One of the most famous expeditions was led by Xu Fu, a court magician, who was sent with a fleet of ships to find the immortals. However, these expeditions were unsuccessful, and Xu Fu did not return, reportedly settling in Japan instead.

Qin Shi Huang’s obsession with immortality had profound consequences for his health and governance. The mercury-based elixirs he consumed likely contributed to his deteriorating health, leading to physical and mental decline in his later years. His increasing paranoia and fear of death also led him to become more isolated, relying heavily on a small circle of trusted advisors and imposing strict security measures to protect himself from perceived threats.

The emperor’s quest for immortality is often seen as a tragic irony, as his relentless pursuit of eternal life may have hastened his death. Qin Shi Huang passed away in 210 BCE during a tour of the eastern provinces, possibly as a result of mercury poisoning from the elixirs he consumed. His death marked the end of his quest for immortality and the beginning of the decline of the Qin Dynasty, which would collapse shortly after his passing.

Death and the Fall of the Qin Dynasty

The death of Qin Shi Huang in 210 BCE was a pivotal moment in Chinese history. The emperor’s passing occurred while he was on a tour of his empire, a journey that had been motivated by his desire to inspect the realm and continue his search for immortality. However, his death was kept secret by his close advisors, including the eunuch Zhao Gao, Prime Minister Li Si, and his younger son, Huhai, who feared that news of the emperor’s death would lead to chaos and rebellion.

In an effort to maintain stability, Zhao Gao and Li Si conspired to alter the emperor’s will, placing Huhai on the throne as the Second Emperor of Qin, known as Qin Er Shi. This decision proved disastrous, as Huhai was ill-prepared for leadership and was heavily influenced by Zhao Gao, who sought to manipulate the new emperor for his own gain. The secrecy surrounding Qin Shi Huang’s death and the subsequent power struggle within the court contributed to the rapid decline of the Qin Dynasty.

The harsh policies and heavy taxation imposed by Qin Shi Huang had already created widespread discontent among the population, and the empire was plagued by rebellions soon after his death. The most significant of these uprisings was led by Chen Sheng and Wu Guang, who were minor officials turned rebel leaders. Their revolt, known as the Dazexiang Uprising, inspired other rebellions across the empire, leading to a wave of unrest that the weak and ineffective Qin Er Shi was unable to quell.

The Qin Dynasty’s downfall was accelerated by Zhao Gao’s machinations, which further destabilized the government. Zhao Gao’s attempts to consolidate power led to purges within the court, including the execution of the loyal Prime Minister Li Si. However, Zhao Gao’s reign of terror eventually backfired, resulting in his own assassination by the very officials he had sought to control.

By 207 BCE, the Qin Dynasty had collapsed under the weight of internal strife and external rebellion. The last emperor, Ziying, who succeeded Qin Er Shi, surrendered to the rebel leader Liu Bang, marking the official end of the Qin Dynasty. Liu Bang would go on to establish the Han Dynasty, which would rule China for the next four centuries. Despite its brief existence, the Qin Dynasty left a lasting legacy, particularly through its centralization of power, standardization of laws, and monumental construction projects.

Legacy and Impact on Chinese History

Qin Shi Huang’s legacy is complex and multifaceted, as his reign had a profound impact on Chinese history, both positive and negative. On one hand, he is celebrated as the unifier of China, a visionary leader who laid the foundations for the Chinese state that would endure for over two millennia. His efforts to centralize power, standardize legal and administrative systems, and promote infrastructure projects like the Great Wall were instrumental in shaping the future of China. These achievements have earned him a place as one of the most important figures in Chinese history.

The unification of China under Qin Shi Huang marked the beginning of a new era in Chinese civilization. The centralized bureaucracy he established served as a model for subsequent dynasties, ensuring the continuity and stability of the Chinese state. His standardization of the Chinese script, weights, measures, and currency facilitated communication, trade, and governance across the vast empire, contributing to the development of a cohesive Chinese identity. The legal and administrative reforms he implemented also set the groundwork for the imperial system that would dominate Chinese governance for centuries.

However, Qin Shi Huang’s legacy is also marred by his authoritarian rule and the harsh methods he employed to achieve his goals. His reign was characterized by extreme measures, including the suppression of intellectual dissent, the use of brutal punishments, and the imposition of heavy taxes and labor demands on the population. These policies, while effective in consolidating power, also created widespread suffering and resentment, ultimately leading to the rapid collapse of the Qin Dynasty after his death.

Qin Shi Huang’s reputation has been the subject of much debate throughout Chinese history. In some periods, he has been vilified as a tyrant whose oppressive rule caused immense hardship and led to the downfall of his dynasty. In other periods, he has been praised as a strong and effective leader who achieved the impossible by uniting China and laying the foundations for its future greatness. Modern historians often view Qin Shi Huang as a complex figure whose legacy cannot be easily categorized as entirely positive or negative.

The physical remnants of Qin Shi Huang’s reign, such as the Great Wall and the Terracotta Army, continue to be powerful symbols of his ambition and vision. These monuments have become iconic representations of China’s ancient history and are recognized as UNESCO World Heritage Sites, attracting millions of visitors from around the world. Through these enduring symbols, Qin Shi Huang’s influence on Chinese history and culture remains palpable, more than two millennia after his death.

Qin Shi Huang in Popular Culture and Historical Memory

Qin Shi Huang has left an indelible mark on popular culture and historical memory, both in China and around the world. His life and reign have been the subject of countless works of literature, art, film, and television, reflecting the enduring fascination with this enigmatic and powerful figure. In Chinese literature, Qin Shi Huang is often portrayed as a larger-than-life character, embodying both the virtues of a strong ruler and the vices of a tyrant. His quest for immortality, his ambitious construction projects, and his ruthless methods of maintaining control have provided rich material for storytellers and artists throughout the centuries.

One of the most famous depictions of Qin Shi Huang in Chinese literature is in the historical novel “Records of the Grand Historian” (Shiji), written by the Han Dynasty historian Sima Qian. In this foundational text of Chinese historiography, Sima Qian presents a detailed and often critical account of Qin Shi Huang’s reign, highlighting both his accomplishments and his flaws. The “Records of the Grand Historian” has influenced subsequent portrayals of Qin Shi Huang, contributing to the complex and often ambivalent image of the emperor in Chinese culture.

In modern times, Qin Shi Huang has been depicted in various forms of media, both in China and internationally. Films such as Zhang Yimou’s “Hero” (2002) offer a dramatized interpretation of the emperor’s efforts to unify China, exploring themes of power, sacrifice, and the moral complexities of rulership. The film presents Qin Shi Huang as a figure whose actions, though ruthless, are ultimately justified by his vision of a unified and peaceful empire. This portrayal reflects a broader trend in Chinese popular culture, where Qin Shi Huang is often depicted as a symbol of national unity and strength, despite the darker aspects of his reign.

Television series and documentaries have also explored the life and legacy of Qin Shi Huang, with some productions emphasizing the grandeur of his achievements, such as the construction of the Terracotta Army, while others focus on the human cost of his rule. The Terracotta Army itself has become one of the most iconic representations of Qin Shi Huang in popular culture. Discovered in 1974 near the emperor’s mausoleum in Xi’an, this vast collection of life-sized clay soldiers, horses, and chariots was created to accompany Qin Shi Huang in the afterlife. The Terracotta Army has captured the imagination of people around the world, becoming a symbol of the emperor’s power and his obsession with immortality.

In addition to film and television, Qin Shi Huang has been the subject of numerous books, both historical and fictional. These works often explore the emperor’s complex personality, his ambitious projects, and his lasting impact on Chinese history. Some authors have delved into the psychological aspects of Qin Shi Huang’s character, examining his fear of death and his desire for control. Others have focused on the historical and cultural significance of his reign, considering how Qin Shi Huang’s policies and innovations shaped the course of Chinese civilization.

Qin Shi Huang’s influence extends beyond China, as his life and reign have been the subject of scholarly research and popular interest around the world. Historians and archaeologists continue to study the Qin Dynasty, uncovering new insights into the emperor’s rule and the society he governed. The international appeal of Qin Shi Huang’s story is reflected in exhibitions and cultural events that showcase artifacts from his reign, including the Terracotta Army, which has been displayed in museums across the globe.

The figure of Qin Shi Huang also appears in various fictional works, including novels, video games, and comic books, where he is often portrayed as a formidable antagonist or a symbol of absolute power. These representations highlight the emperor’s enduring presence in the global cultural imagination, where he is both admired and feared for his achievements and his authoritarian rule.

In historical memory, Qin Shi Huang occupies a unique place as the first emperor of a unified China. His legacy is commemorated in various ways, from the preservation of his mausoleum and the Terracotta Army to the celebration of his contributions to Chinese statehood. At the same time, his reign serves as a cautionary tale about the dangers of absolute power and the human cost of imperial ambition.

In contemporary China, Qin Shi Huang’s image has been reinterpreted in the context of national pride and cultural heritage. While his authoritarian methods are acknowledged, his role in forging a unified Chinese identity is often emphasized. This reflects a broader trend in which historical figures are re-evaluated in light of modern values and priorities. Qin Shi Huang’s story continues to be told and retold, resonating with new generations and contributing to the ongoing dialogue about power, legacy, and the complexities of leadership.

Qin Shi Huang’s Mausoleum and the Terracotta Army

Qin Shi Huang’s mausoleum, located near the modern city of Xi’an in Shaanxi Province, is one of the most remarkable archaeological sites in the world. The tomb complex, which covers an area of approximately 56 square kilometers, was constructed over several decades and involved the labor of hundreds of thousands of workers. The mausoleum is a testament to Qin Shi Huang’s vision of immortality and his desire to maintain his power and influence in the afterlife.

The most famous feature of the mausoleum is the Terracotta Army, a vast collection of life-sized clay soldiers, horses, and chariots that were buried with the emperor to protect him in the afterlife. Discovered in 1974 by local farmers, the Terracotta Army is composed of over 8,000 figures, each with unique facial features, uniforms, and weaponry. The figures are arranged in battle formation, reflecting the military might of the Qin Dynasty and the emperor’s obsession with security.

The construction of the Terracotta Army and the mausoleum as a whole was a monumental undertaking that required immense resources and labor. According to historical records, the project began shortly after Qin Shi Huang ascended the throne and continued throughout his reign. The labor force included skilled artisans, craftsmen, and laborers who were conscripted from across the empire. The scale of the project and the complexity of the figures indicate a high level of craftsmanship and organization, as well as the emperor’s determination to create a lasting legacy.

The mausoleum itself is believed to be a vast underground palace, complete with rivers of mercury and a ceiling adorned with constellations. Historical accounts, such as those in Sima Qian’s “Records of the Grand Historian,” describe the tomb as a microcosm of the emperor’s empire, designed to mirror the world above and ensure Qin Shi Huang’s dominance in the afterlife. However, the central tomb chamber has not yet been excavated, due in part to concerns about preserving the site and the potential hazards posed by the high levels of mercury that have been detected in the area.

The discovery of the Terracotta Army has provided invaluable insights into the art, technology, and military organization of the Qin Dynasty. The figures themselves are a masterpiece of ancient Chinese sculpture, with each soldier meticulously crafted to reflect different ranks and roles within the army. The attention to detail in the armor, weapons, and facial expressions of the figures suggests a sophisticated understanding of both military organization and artistic representation.

In addition to the soldiers, the mausoleum complex includes a variety of other figures and artifacts, such as acrobats, musicians, and animals, which were intended to provide entertainment and support for the emperor in the afterlife. These figures offer a glimpse into the daily life and culture of the Qin Dynasty, as well as the emperor’s desire to recreate his court and empire in the afterlife.

The Terracotta Army and the mausoleum have become iconic symbols of Qin Shi Huang’s reign and are recognized as one of the greatest archaeological discoveries of the 20th century. The site was designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1987 and has since attracted millions of visitors from around the world. The ongoing excavation and study of the site continue to reveal new information about the Qin Dynasty and the life of its first emperor.

The legacy of Qin Shi Huang’s mausoleum and the Terracotta Army extends beyond their historical and cultural significance. They serve as a powerful reminder of the emperor’s ambition and his desire to control not only the world of the living but also the afterlife. The sheer scale and complexity of the mausoleum project reflect the immense resources and power that Qin Shi Huang wielded during his reign, as well as the lengths to which he was willing to go to secure his legacy.

In modern times, the Terracotta Army has become a symbol of Chinese cultural heritage and a source of national pride. The figures have been featured in exhibitions around the world, showcasing the artistry and technological achievements of ancient China. The site continues to be a focal point for research, conservation, and public interest, ensuring that the legacy of Qin Shi Huang and his mausoleum will endure for generations to come.