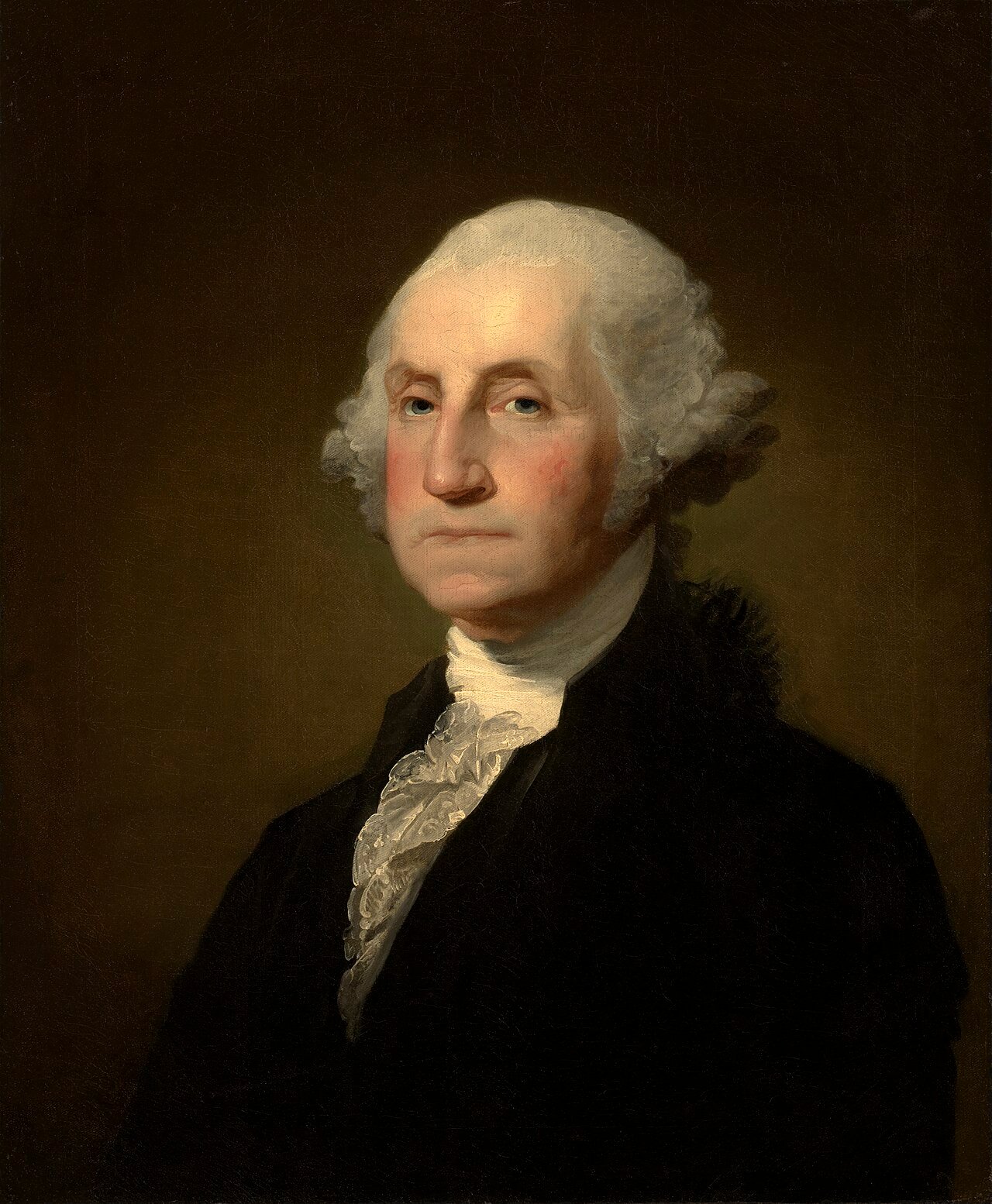

George Washington (1732–1799) was a pivotal figure in American history, renowned as the first President of the United States and the leader of the Continental Army during the American Revolutionary War. Born in Virginia, Washington gained early experience in land surveying and military leadership. His leadership during the Revolution was crucial in securing American independence from British rule. After the war, Washington presided over the Constitutional Convention, where his reputation for integrity and leadership helped shape the new nation’s framework. In 1789, he became the first U.S. President, setting many precedents for the office, including the peaceful transfer of power. Washington’s leadership, characterized by a deep sense of duty and commitment to republican principles, earned him the title “Father of His Country.” His legacy continues to influence American governance and national identity.

Early Life and Family Background

George Washington was born on February 22, 1732, in Westmoreland County, Virginia. His family was part of the Virginia gentry, and he was the eldest son of Augustine Washington and his second wife, Mary Ball Washington. The Washington family had English roots, having emigrated from England to Virginia in 1657. George’s great-grandfather, John Washington, had established the family’s presence in the New World, and over the years, the family had become well-known and respected within colonial society.

George’s father, Augustine, was a prosperous planter and owned several plantations. His first marriage to Jane Butler produced four children, but only two survived infancy. After Jane’s death in 1729, Augustine married Mary Ball, and together they had six children, with George being the eldest. Growing up, George was influenced by the values and expectations of Virginia’s colonial gentry, which emphasized land ownership, social status, and the importance of public service.

The Washington family resided at Pope’s Creek Plantation during George’s early years, but they moved to Ferry Farm, near Fredericksburg, in 1738. As a child, George was educated at home by private tutors, as was customary for children of his social standing. He received instruction in reading, writing, arithmetic, and surveying. However, his formal education was cut short when his father died in 1743, leaving the family in a precarious financial situation. George was only 11 years old at the time, and his half-brother Lawrence became a father figure to him.

Lawrence Washington was a significant influence on young George. Having served in the British Navy and participated in the ill-fated expedition to Cartagena, Lawrence returned to Virginia as a respected veteran and took charge of the family’s affairs. He inherited Mount Vernon, a plantation that would later become George’s home and the centerpiece of his life. Lawrence’s connections with the Fairfax family, one of Virginia’s most prominent families, also provided George with opportunities for social advancement and introduced him to the world of Virginia’s colonial elite.

Despite the family’s financial challenges, George was determined to make a name for himself. He developed a strong interest in surveying, a skill that was highly valued in the expanding colony. At the age of 16, George secured his first job as a surveyor for the powerful Fairfax family, mapping out lands in the western territories of Virginia. This experience not only honed his skills but also introduced him to the rugged frontier and the complexities of colonial land ownership.

In 1751, tragedy struck when Lawrence Washington, who had been suffering from tuberculosis, passed away. George inherited Mount Vernon, though he would not take full possession until Lawrence’s widow died in 1761. The loss of his brother was a turning point in George’s life, pushing him further into the role of head of the family and deepening his resolve to succeed.

The early years of George Washington’s life were marked by a blend of privilege and adversity. While he was born into a prominent family, the early death of his father and the loss of his brother forced him to mature quickly and take on responsibilities beyond his years. These formative experiences, coupled with his exposure to the Virginia gentry and the frontier, laid the groundwork for the man who would later become a central figure in the founding of the United States.

Military Beginnings: The French and Indian War

George Washington’s military career began in earnest during the French and Indian War, a conflict that would serve as a proving ground for his leadership skills and military acumen. The war, which lasted from 1754 to 1763, was the North American theater of the larger Seven Years’ War between Great Britain and France. The conflict was fueled by competition for territorial control in the Ohio Valley, a region both the British and the French sought to dominate due to its strategic importance and potential for expansion.

In 1752, George Washington was appointed as a major in the Virginia militia, a position that reflected his growing reputation as a capable and ambitious young man. His first significant assignment came in 1753 when Governor Robert Dinwiddie of Virginia selected Washington, then only 21 years old, to deliver a message to the French, demanding they vacate the Ohio Valley. The mission required Washington to traverse the rugged and dangerous frontier to reach the French fortifications. Though the French politely refused the request, Washington’s successful completion of the mission earned him recognition and respect.

The following year, in 1754, Washington was promoted to lieutenant colonel and tasked with leading a small force to confront the French in the Ohio Valley. This mission culminated in the Battle of Jumonville Glen, where Washington’s troops ambushed a French scouting party. The skirmish resulted in the death of the French commander, Ensign Joseph Coulon de Jumonville, an event that escalated tensions and contributed to the outbreak of full-scale war. Washington’s role in the encounter, though controversial, brought him to the attention of colonial and British authorities.

Shortly after, Washington and his men hastily constructed Fort Necessity, a makeshift fortification intended to defend against an anticipated French counterattack. The French, however, launched a larger force, leading to the Battle of Fort Necessity in July 1754. The battle was a disaster for Washington; his outnumbered and ill-prepared troops were forced to surrender. The terms of the surrender, written in French, implicated Washington in the death of Jumonville, a diplomatic embarrassment that he would later regret. Despite this early setback, Washington’s conduct during the campaign demonstrated his determination and resolve, qualities that would define his military career.

In 1755, Washington served as an aide-de-camp to General Edward Braddock, the British commander-in-chief in North America. Braddock’s campaign aimed to capture the French Fort Duquesne, located at the confluence of the Allegheny and Monongahela Rivers (present-day Pittsburgh). Washington advised Braddock on the challenges of frontier warfare, emphasizing the need for flexibility and caution. However, Braddock, a seasoned European officer, dismissed Washington’s advice, leading to disastrous consequences.

The campaign culminated in the Battle of the Monongahela, where Braddock’s forces were ambushed by a combined French and Native American force. The battle was a catastrophic defeat for the British, with Braddock mortally wounded and the majority of his troops killed or wounded. Washington emerged from the battle as a hero, despite the defeat. He had shown remarkable bravery and leadership, rallying the remnants of the army and leading a successful retreat. His efforts during the battle earned him the admiration of his peers and the moniker “the hero of the Monongahela.”

Following Braddock’s defeat, Washington was appointed commander of all Virginia forces, a position that gave him responsibility for defending the colony’s frontier. Over the next few years, Washington faced numerous challenges, including managing a poorly trained and ill-equipped militia, dealing with supply shortages, and coordinating with often uncooperative colonial governments. Despite these obstacles, he worked tirelessly to improve the effectiveness of his troops, building a chain of defensive forts along the frontier and leading several expeditions against hostile Native American forces.

The French and Indian War was a formative experience for Washington, shaping his views on military leadership, colonial governance, and the relationship between the colonies and Britain. It also exposed him to the complexities of warfare in the American wilderness, lessons that would prove invaluable during the Revolutionary War. By the war’s end in 1763, Washington had established himself as one of the leading military figures in Virginia, a status that would propel him into the forefront of the colonial resistance against British rule.

The Road to Revolution

As the French and Indian War came to a close, George Washington returned to Mount Vernon, where he focused on managing his plantation and expanding his agricultural enterprises. However, the experiences and frustrations he encountered during the war left a lasting impact on his views toward British colonial policies. Washington’s growing discontent with British rule, coupled with the rising tensions between the colonies and the British government, set him on the path to becoming a leader in the American Revolution.

The aftermath of the French and Indian War saw Britain saddled with a massive debt, leading the British government to seek new revenue sources from its American colonies. This led to a series of taxes and regulations imposed on the colonies, starting with the Sugar Act of 1764 and the more infamous Stamp Act of 1765. The Stamp Act, which required colonists to purchase and use specially stamped paper for legal documents, newspapers, and other publications, was particularly unpopular. It marked the first direct tax levied by Britain on the colonies and was seen as a violation of the principle of “no taxation without representation.”

Washington, like many of his fellow Virginians, was outraged by the Stamp Act. He viewed it as an unconstitutional infringement on colonial liberties and a dangerous precedent for further British encroachments. While Washington did not yet advocate for independence, he became increasingly vocal in his opposition to British policies. He supported the resolutions passed by the Virginia House of Burgesses, which declared the Stamp Act unconstitutional and called for its repeal. Washington’s involvement in these early protests marked his entry into the political arena as a defender of colonial rights.

The repeal of the Stamp Act in 1766 provided only temporary relief, as the British government soon introduced other measures that further inflamed colonial resentment. The Townshend Acts of 1767, which imposed duties on imported goods such as tea, glass, and paper, sparked renewed protests and boycotts across the colonies. Washington participated in the non-importation movement, agreeing to boycott British goods as a means of pressuring Parliament to repeal the taxes. He also began to advocate for economic self-sufficiency, encouraging his fellow planters to reduce their reliance on British imports and increase domestic production.

The escalation of tensions between the colonies and the British government continued to build throughout the late 1760s and early 1770s. Events such as the Boston Massacre in 1770 and the imposition of the Tea Act in 1773, which led to the Boston Tea Party, further deepened the divide. Washington, while initially cautious about the prospect of armed conflict, became increasingly convinced that the colonies needed to take a firmer stand against British tyranny.

The Intolerable Acts, passed by the British Parliament in 1774 in response to the Boston Tea Party, were a turning point for Washington and many other colonial leaders. These acts, which included the closing of Boston Harbor and the dissolution of Massachusetts’ colonial government, were seen as a direct attack on the liberties of all the colonies. In response, the First Continental Congress was convened in September 1774 in Philadelphia, where representatives from twelve of the thirteen colonies gathered to coordinate a unified response to British aggression.

Washington was elected as one of Virginia’s delegates to the Congress, marking his first significant involvement in the broader colonial resistance movement. At the Congress, Washington advocated for a strong, united front against British policies and supported the adoption of non-importation agreements as a form of economic protest. While the Congress sought to avoid open conflict and still expressed loyalty to King George III, it also prepared for the possibility of war by establishing the Continental Association to enforce the boycotts and calling for the formation of local militias.

By the time the Second Continental Congress convened in May 1775, the situation had deteriorated further. The battles of Lexington and Concord in April 1775 marked the outbreak of open hostilities between colonial militias and British troops. Washington arrived at the Congress wearing his military uniform, signaling his readiness to take up arms in defense of colonial rights. His leadership and military experience made him an obvious choice when Congress decided to appoint a commander-in-chief for the newly formed Continental Army.

On June 15, 1775, George Washington was unanimously selected as the commander-in-chief of the Continental Army. He accepted the position with a mixture of humility and determination, recognizing the enormous challenges that lay ahead. Washington declined a salary for his service, asking only for reimbursement of his expenses, a gesture that underscored his commitment to the cause.

As Washington prepared to take command of the Continental Army, he faced the daunting task of transforming a loosely organized and poorly equipped collection of colonial militias into a cohesive fighting force capable of standing up to the professional British Army. He was acutely aware of the stakes involved; failure could mean the loss of everything he and his fellow colonists held dear. Nevertheless, Washington was resolute in his belief that the colonies’ fight for their rights and liberties was just and necessary.

Washington’s selection as commander-in-chief marked the beginning of his pivotal role in the American Revolution. Over the next several years, he would face numerous trials and tribulations as he led the Continental Army through the darkest days of the war. His leadership during this critical period would not only shape the outcome of the Revolution but also establish him as one of the most important figures in American history.

The Revolutionary War: Leadership and Challenges

George Washington’s leadership during the Revolutionary War was characterized by resilience, strategic acumen, and an unwavering commitment to the cause of American independence. From the outset, he faced a series of daunting challenges as he sought to organize and sustain the Continental Army in the face of overwhelming odds.

When Washington took command of the Continental Army in July 1775, he found the situation in Boston, where the British had a stronghold, to be dire. The American forces, while spirited, were disorganized, poorly trained, and lacking in supplies. Washington quickly set about imposing discipline and order, working to instill a sense of professionalism among the troops. He also recognized the need for a long-term strategy that would enable the colonies to sustain a protracted conflict against a superior foe.

One of Washington’s earliest challenges was the Siege of Boston. The British forces, led by General Thomas Gage, were entrenched in the city, while the Continental Army surrounded them in a loose blockade. Washington understood that a direct assault on Boston would be too costly, so he instead focused on fortifying the American positions and cutting off British supply lines. The turning point came in March 1776, when Washington, using heavy artillery captured from Fort Ticonderoga, successfully fortified Dorchester Heights, overlooking Boston. The British, realizing their vulnerable position, evacuated the city on March 17, 1776, marking Washington’s first significant victory of the war.

Following the victory in Boston, Washington faced a new and even greater challenge as the British shifted their focus to New York. Recognizing the strategic importance of New York City, Washington moved his forces to defend it. However, the British, under General William Howe, launched a massive amphibious assault in the summer of 1776, overwhelming the Continental Army in the Battle of Long Island. Washington’s forces suffered heavy losses, and he was forced to execute a daring nighttime retreat across the East River to Manhattan, avoiding complete annihilation.

The subsequent months were marked by a series of setbacks for Washington and the Continental Army. The British captured New York City and pursued Washington’s forces across New Jersey. By the end of 1776, morale among the American troops was at an all-time low, and the cause of independence seemed on the brink of collapse. Washington, however, refused to give up. In a bold and unexpected move, he crossed the icy Delaware River on Christmas night, 1776, and launched a surprise attack on the Hessian forces in Trenton, New Jersey. The victory at the Battle of Trenton, followed by another success at the Battle of Princeton, revitalized the American cause and demonstrated Washington’s ability to inspire and lead his men in the face of adversity.

Despite these successes, Washington’s challenges were far from over. The winter of 1777-1778, spent at Valley Forge, Pennsylvania, was one of the darkest periods of the war. The Continental Army endured extreme cold, hunger, and disease, with many soldiers lacking proper clothing and shelter. Washington’s leadership during this time was crucial in maintaining the army’s cohesion and morale. He worked tirelessly to secure supplies, improve training, and care for his men. The arrival of Baron Friedrich von Steuben, a Prussian military officer, was a turning point, as he implemented a rigorous training program that significantly improved the discipline and effectiveness of the Continental Army.

As the war dragged on, Washington faced not only the British forces but also internal challenges, including political interference from Congress, disputes among his generals, and the constant struggle to secure funding and supplies. Despite these obstacles, he remained focused on the ultimate goal of securing independence for the colonies.

Washington’s strategic vision and ability to adapt to changing circumstances were key to his success. He recognized that the war would not be won by a single decisive battle but by wearing down the British forces through a war of attrition. He also understood the importance of alliances, particularly with France, which provided critical military and financial support to the American cause.

The Revolutionary War reached its climax in 1781 with the Siege of Yorktown. Washington, in coordination with French forces under General Rochambeau, managed to trap the British army, led by General Cornwallis, on the Yorktown Peninsula in Virginia. After a grueling siege, Cornwallis was forced to surrender on October 19, 1781, effectively ending major combat operations and securing American independence.

Washington’s leadership during the Revolutionary War cemented his legacy as a pivotal figure in American history. His ability to persevere through hardship, his commitment to the principles of liberty, and his strategic acumen were instrumental in achieving victory against one of the world’s most powerful empires. As the war came to a close, Washington faced the next great challenge of his life: guiding the fledgling nation through its early years and helping to shape the government that would sustain the ideals for which he had fought.

The Constitutional Convention and the Presidency

With the end of the Revolutionary War, George Washington returned to Mount Vernon, eager to resume his life as a private citizen. However, the challenges facing the newly independent United States soon drew him back into public service. The Articles of Confederation, the first governing document of the United States, had proven inadequate for managing the nation’s affairs. The lack of a strong central government led to economic instability, interstate conflicts, and an inability to address pressing national issues. Recognizing the need for a more effective system of government, Washington agreed to attend the Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia in 1787.

Washington’s presence at the Convention lent it an air of legitimacy and importance. He was unanimously elected as the president of the Convention, a role that saw him preside over the debates and ensure that the proceedings were conducted with order and decorum. While Washington did not participate extensively in the debates, his influence was nonetheless profound. His support for a strong central government, tempered by a system of checks and balances, helped guide the framers as they crafted the Constitution.

The result of the Convention’s work was a new Constitution that created a federal system of government with separate executive, legislative, and judicial branches. Washington’s leadership and reputation for integrity were instrumental in securing the Constitution’s ratification. He was widely regarded as the only man capable of uniting the nation and ensuring the success of the new government. When the Constitution was ratified in 1788, there was little doubt that Washington would be the first President of the United States.

Washington was unanimously elected as the first President by the Electoral College in 1789. He took the oath of office on April 30, 1789, on the balcony of Federal Hall in New York City, then the nation’s capital. As the first President, Washington was acutely aware that his actions and decisions would set precedents for future leaders. He approached the presidency with a deep sense of duty and a commitment to the principles of the Constitution. Washington was mindful that his every action would establish a precedent for future leaders, and he took great care in shaping the role of the presidency with integrity and respect for the democratic principles outlined in the new Constitution.

One of Washington’s first major tasks as President was to establish a functioning federal government. This required not only appointing capable leaders to head the newly created executive departments but also creating an effective system of governance that would ensure stability and efficiency. Washington’s choices for his cabinet reflected his desire for a government led by individuals of character and ability. He appointed Thomas Jefferson as Secretary of State, Alexander Hamilton as Secretary of the Treasury, Henry Knox as Secretary of War, and Edmund Randolph as Attorney General. This group of advisors, known as Washington’s cabinet, played a crucial role in shaping the policies of the new government.

Washington’s administration faced a number of significant challenges in its early years. One of the most pressing was the need to establish a stable financial system for the new nation. Alexander Hamilton, as Secretary of the Treasury, proposed a series of measures to strengthen the nation’s economy, including the creation of a national bank, the assumption of state debts by the federal government, and the implementation of tariffs and taxes to generate revenue. These proposals were highly controversial and led to the first major political divisions in the United States. Washington, recognizing the importance of a strong economy, supported Hamilton’s plans despite opposition from Thomas Jefferson and James Madison, who feared that Hamilton’s policies would centralize too much power in the federal government.

Another significant challenge during Washington’s presidency was the need to assert the authority of the federal government in maintaining law and order. This issue came to the forefront during the Whiskey Rebellion of 1794, when farmers in western Pennsylvania protested a federal excise tax on whiskey. The rebellion posed a serious threat to the stability of the new government, and Washington responded by calling up a militia force to suppress the uprising. His decisive action in quelling the rebellion demonstrated the federal government’s ability to enforce its laws and maintain order, setting an important precedent for the future.

In addition to domestic challenges, Washington also had to navigate the complexities of foreign relations. The young United States was still a relatively weak nation on the global stage, and Washington was determined to keep the country out of the conflicts that were raging in Europe, particularly between Britain and France. In 1793, he issued the Proclamation of Neutrality, declaring that the United States would remain impartial in the war between Britain and France. This decision was met with criticism from both pro-British and pro-French factions within the country, but Washington believed that avoiding entanglement in European conflicts was essential for the nation’s security and prosperity.

Washington’s leadership in foreign policy was further tested by the Jay Treaty of 1794, which was negotiated by Chief Justice John Jay to resolve outstanding issues between the United States and Britain. The treaty, which sought to prevent another war with Britain, was highly controversial and sparked intense debate in the United States. Many Americans felt that the treaty was too favorable to Britain and did not adequately address the issue of British interference with American shipping. Despite the controversy, Washington supported the treaty, believing that it was the best way to preserve peace and stability. His decision to sign the treaty, despite the political fallout, underscored his commitment to the long-term interests of the nation.

Throughout his presidency, Washington was acutely aware of the need to balance the competing interests of different regions, factions, and political ideologies. He sought to govern in a way that would promote national unity and avoid the formation of political parties, which he feared would lead to factionalism and division. Despite his efforts, political parties began to emerge during his administration, with the Federalists, led by Hamilton, advocating for a strong central government, and the Democratic-Republicans, led by Jefferson, championing states’ rights and limited federal power.

Washington’s presidency also set important precedents in the area of presidential authority and the relationship between the executive and legislative branches. He established the tradition of seeking the advice and consent of the Senate for treaties and appointments, while also asserting the president’s authority to conduct foreign policy and oversee the executive branch. Washington’s careful balancing of executive power with respect for the other branches of government helped to shape the office of the presidency and ensure its role within the framework of the Constitution.

As his second term drew to a close, Washington made the momentous decision not to seek a third term in office. His decision to voluntarily step down from power set a precedent for the peaceful transfer of power and reinforced the principle that the presidency was not a lifetime position. In 1796, he delivered his Farewell Address, a letter to the American people in which he offered advice and reflections on the nation’s future. In this address, Washington warned against the dangers of political parties, foreign alliances, and sectionalism, and he urged the country to remain united and focused on the common good.

Washington’s decision to retire from public life marked the end of an era in American history. He had guided the young nation through its formative years, establishing the institutions and practices that would sustain it for generations to come. His leadership, wisdom, and dedication to the principles of the Constitution earned him the enduring respect and admiration of his fellow citizens and cemented his legacy as the “Father of His Country.”

Retirement and Legacy

After leaving the presidency in 1797, George Washington returned to Mount Vernon, where he hoped to spend his remaining years in peace and tranquility. Despite his desire for a quiet retirement, Washington remained deeply concerned about the future of the nation he had helped to create. He continued to correspond with political leaders, offering advice and guidance on matters of national importance. His influence, though no longer official, was still felt in the political life of the young republic.

In retirement, Washington focused on managing his plantation at Mount Vernon, which had suffered during the years he was away leading the Continental Army and serving as President. He worked to improve the productivity of his lands and implemented innovative agricultural practices, such as crop rotation and the use of fertilizers. Washington also took a keen interest in the welfare of his slaves, though he continued to hold them in bondage. Over time, he grew increasingly troubled by the institution of slavery, and in his will, he made the bold decision to free all of his slaves upon the death of his wife, Martha.

Washington’s retirement was interrupted by the growing tensions between the United States and France, which threatened to erupt into war. In 1798, President John Adams appointed Washington as commander-in-chief of the U.S. Army in anticipation of a potential conflict with France. Although Washington was reluctant to return to military service, he accepted the appointment and worked to organize and prepare the army for the possibility of war. Fortunately, the conflict was averted, and Washington was able to return to Mount Vernon, where he continued to oversee his estate.

On December 12, 1799, Washington caught a cold after riding on his estate in cold and wet weather. His condition quickly worsened, and by the evening of December 14, he was gravely ill. Despite the best efforts of his doctors, who employed the common medical practices of the time, including bloodletting, Washington’s condition continued to deteriorate. He faced his impending death with the same calm and resolve that had characterized his life, giving instructions for his burial and expressing his readiness to meet his end.

George Washington passed away on December 14, 1799, at the age of 67. His death was met with an outpouring of grief and mourning across the United States and around the world. Washington’s passing marked the end of an era, and his legacy as a leader, statesman, and symbol of the nation’s ideals was immediately recognized and honored. Congress passed a resolution declaring a period of national mourning, and tributes to Washington’s life and achievements were delivered in communities across the country.

In the years since his death, Washington’s legacy has only grown in stature. He is remembered not only as the commander who led the American colonies to victory in the Revolutionary War but also as the statesman who helped shape the nation’s government and ensure its survival during its early years. Washington’s leadership was defined by his commitment to the principles of liberty, self-governance, and civic virtue. He understood the importance of setting a good example for future generations and took care to act with integrity and honor in all aspects of his public and private life.

Washington’s legacy is also reflected in the numerous monuments, memorials, and institutions that bear his name. The most prominent of these is the Washington Monument in the nation’s capital, a towering obelisk that symbolizes his enduring influence on American history. His image appears on the U.S. dollar bill and the quarter, and his birthday, February 22, is celebrated as a federal holiday known as Presidents’ Day.

Perhaps Washington’s most lasting contribution to the nation is the precedent he set for the peaceful transfer of power. By voluntarily stepping down from the presidency after two terms, Washington established a tradition of democratic leadership that has become a cornerstone of the American political system. His Farewell Address, with its warnings against factionalism and foreign entanglements, remains a guiding document for American statesmen and a testament to his foresight and wisdom.

In the centuries since his death, George Washington has come to be revered as the quintessential American hero—a man of courage, vision, and unwavering commitment to the principles of freedom and democracy. His legacy continues to inspire generations of Americans, serving as a reminder of the values upon which the nation was founded and the responsibilities of citizenship in a free society. Washington’s life and achievements are a testament to the power of leadership, character, and the enduring impact that one individual can have on the course of history.