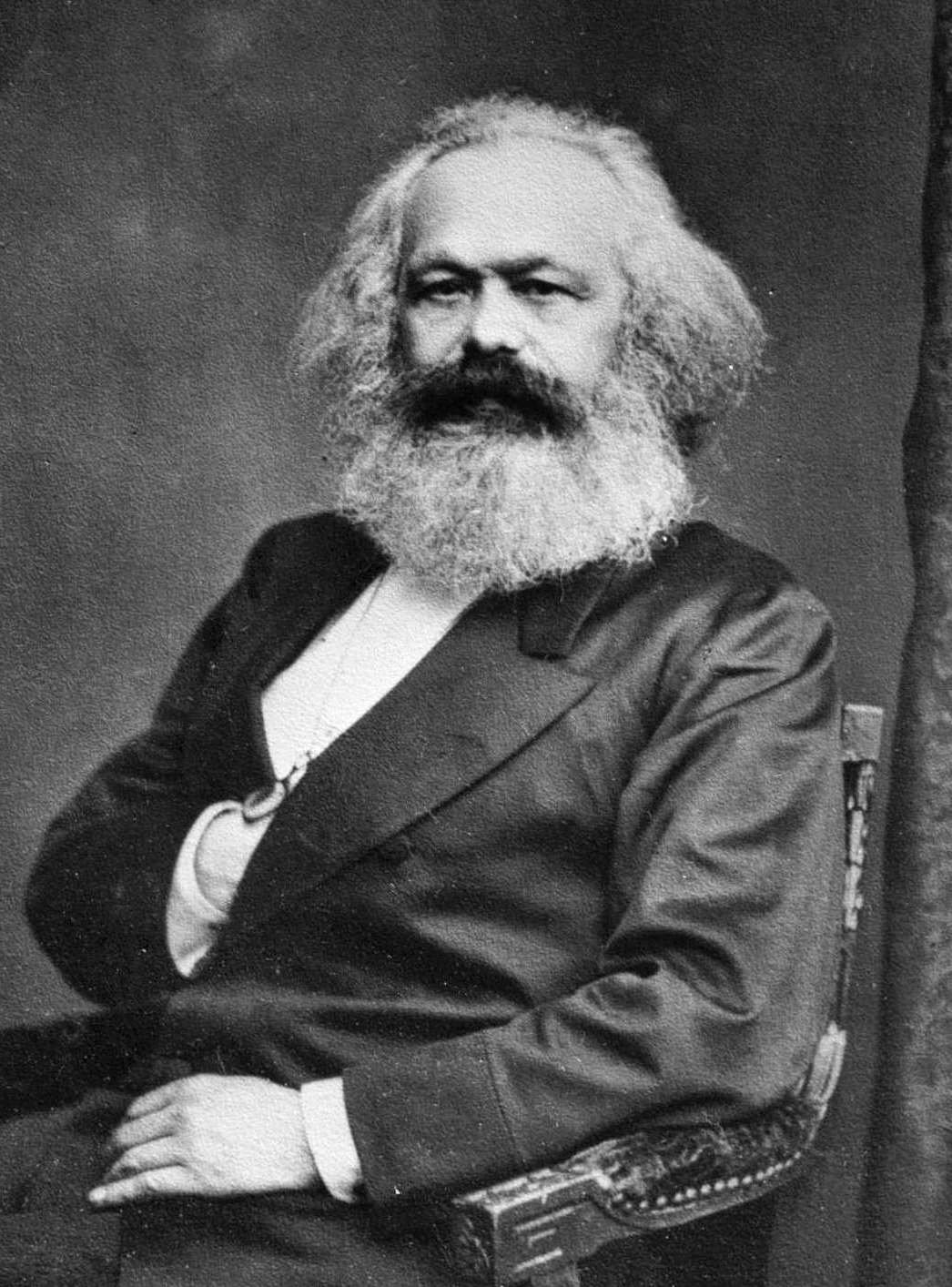

Karl Marx (1818–1883) was a German philosopher, economist, historian, and political theorist, best known for his critical analysis of capitalism and his influence on modern socialist and communist thought. Born in Trier, Germany, Marx studied law and philosophy, eventually developing a radical critique of existing socio-economic systems. His most famous works, “The Communist Manifesto” (1848) and “Das Kapital” (1867), laid out his theory of historical materialism, arguing that all human history is driven by class struggles. Marx believed that capitalism would inevitably lead to its own downfall through the exploitation of the working class, paving the way for a classless, stateless society. His ideas, collectively known as Marxism, have profoundly impacted global political movements, inspiring revolutions and shaping the development of socialist and communist states in the 20th century. Marx remains one of the most influential and controversial figures in modern history.

Early Life and Background (1818-1835)

Karl Marx was born on May 5, 1818, in Trier, a small town in the Rhineland region of Prussia, which is present-day Germany. He was the third of nine children in a middle-class Jewish family. His father, Heinrich Marx, was a successful lawyer who converted to Protestantism in 1816 to maintain his legal practice, as Jews faced restrictions under the Prussian legal system. His mother, Henriette Pressburg, came from a relatively wealthy Jewish family in the Netherlands. Despite their Jewish roots, Karl was baptized into the Lutheran Church at a young age, reflecting the pragmatic decisions made by his father in the context of the political and social environment of the time.

Marx’s early education took place at home under his father’s supervision, who instilled in him a love for literature and philosophy. In 1830, at the age of 12, Marx enrolled in the Trier High School, where he displayed a keen interest in classical studies, especially in Latin and Greek. His school reports described him as a promising student with an independent mind, which sometimes got him into trouble with the authorities. The political atmosphere of the time was charged with the aftereffects of the Napoleonic Wars and the subsequent restoration of conservative monarchies across Europe. The intellectual climate in Trier, however, was somewhat liberal, influenced by the French Revolution and the Enlightenment, which laid the groundwork for Marx’s later radical ideas.

At the age of 17, Marx graduated from high school and enrolled at the University of Bonn to study law, as his father wished. However, his interests soon shifted towards philosophy and literature, leading to conflicts with his father. Marx’s time at Bonn was marked by a period of personal exploration, during which he joined a number of student organizations, including a drinking club, and got involved in dueling, a popular student activity at the time. However, his academic performance was less than stellar, and after a year, his father insisted that he transfer to a more rigorous university to focus on his studies.

University Years and Intellectual Awakening (1835-1843)

In 1836, Marx transferred to the University of Berlin, a leading center for philosophical thought in Germany, particularly influenced by the teachings of Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel. It was here that Marx’s intellectual journey took a decisive turn. At Berlin, Marx was introduced to the Young Hegelians, a group of radical thinkers who sought to apply Hegel’s dialectical method to critique religion, politics, and society. The Young Hegelians were critical of the conservative Prussian state and the religious orthodoxy that supported it, and they believed that reason and human freedom should be the driving forces of history.

Marx quickly became engrossed in the works of Hegel and joined the Doktorklub, a society of young intellectuals who discussed Hegelian philosophy and its implications for contemporary society. During this time, he also began writing poetry and fiction, though these early literary efforts were not successful and were later abandoned. Marx’s focus gradually shifted from literature to philosophy, as he became more deeply engaged with the ideas of Hegel and the critical philosophy of Ludwig Feuerbach, who argued that religious beliefs were projections of human desires and that human emancipation required the critique of religion.

In 1841, Marx completed his doctoral dissertation, titled “The Difference Between the Democritean and Epicurean Philosophy of Nature,” which reflected his interest in ancient materialist philosophy. Despite the dissertation’s esoteric subject matter, it showcased Marx’s analytical abilities and his growing commitment to materialist philosophy, which would later form the basis of his critique of political economy. However, due to his radical views and associations with the Young Hegelians, Marx found it difficult to secure an academic position in the increasingly conservative Prussian university system. Disillusioned with academia, Marx turned towards journalism as a means to engage with political and social issues.

In 1842, Marx moved to Cologne, where he became the editor of the Rheinische Zeitung, a liberal newspaper that was critical of the Prussian government. Under Marx’s editorship, the newspaper took a more radical stance, addressing issues such as freedom of the press, economic inequality, and the plight of the working class. However, Marx’s outspoken criticism of the government and his advocacy for democratic reforms soon attracted the attention of the authorities, leading to the newspaper’s suppression in 1843. This experience further radicalized Marx and convinced him that philosophical critique alone was insufficient; what was needed was revolutionary change.

Marriage, Exile, and Political Engagement (1843-1848)

In June 1843, shortly after the suppression of the Rheinische Zeitung, Marx married Jenny von Westphalen, his childhood sweetheart and the daughter of a prominent Prussian baron. Despite the social and political differences between their families, Jenny was deeply committed to Marx’s ideas and played a crucial role in supporting his work throughout their marriage. The couple moved to Paris later that year, where Marx began to immerse himself in the vibrant intellectual and political life of the French capital.

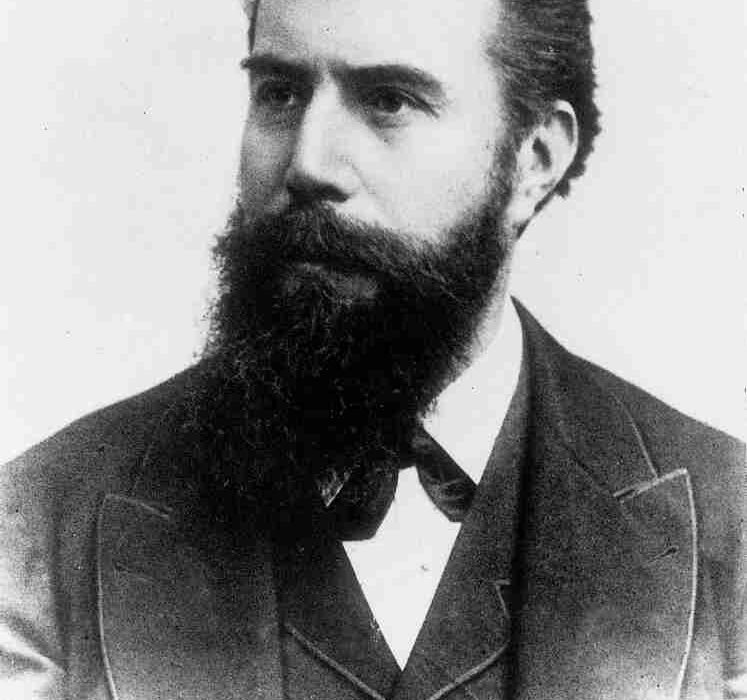

Paris was a hub for revolutionary thought and political activism, and it was here that Marx first encountered socialism and communism. He began to read the works of socialist thinkers like Henri de Saint-Simon and Charles Fourier, as well as the writings of contemporary French socialists. Marx also met Friedrich Engels, the son of a wealthy German industrialist, who would become his closest collaborator and lifelong friend. Engels introduced Marx to the conditions of the working class in industrial England and the realities of capitalist exploitation, which had a profound impact on Marx’s thinking.

In 1844, Marx and Engels co-authored “The Holy Family,” a critique of the Young Hegelians and a defense of materialism. This work marked the beginning of their intellectual partnership, which would produce some of the most influential works in the history of political thought. During this period, Marx also wrote the “Economic and Philosophical Manuscripts of 1844,” in which he explored the concept of alienation under capitalism, arguing that workers are alienated from the products of their labor, from the act of production itself, from their fellow workers, and from their own human potential. These manuscripts, though unpublished during Marx’s lifetime, laid the groundwork for his later critique of political economy.

Marx’s revolutionary activities in Paris attracted the attention of the Prussian government, which pressured the French authorities to expel him. In 1845, Marx was forced to move to Brussels, where he continued his political work in exile. In Brussels, Marx and Engels joined the Communist League, a secret organization of revolutionary socialists, and began to develop their theory of historical materialism, which posited that the history of all hitherto existing societies is the history of class struggles. They argued that the capitalist mode of production would inevitably lead to its own downfall, as the proletariat, or working class, would rise up against the bourgeoisie, or capitalist class, and establish a classless, communist society.

In 1847, the Communist League commissioned Marx and Engels to write a manifesto outlining their views. The result was the “Communist Manifesto,” published in early 1848, which famously declared, “Workers of the world, unite!” The manifesto outlined the principles of communism, critiqued the existing capitalist system, and called for the overthrow of the bourgeoisie by the proletariat. The publication of the manifesto coincided with a wave of revolutionary uprisings across Europe in 1848, which Marx and Engels actively supported. Although these revolutions ultimately failed, the manifesto would go on to become one of the most influential political documents in history.

The Revolutionary Years and Further Exile (1848-1850)

The year 1848 was marked by a series of revolutionary upheavals across Europe, often referred to as the Springtime of Nations. These revolutions, which were driven by demands for political liberalization, social reforms, and national independence, provided Marx and Engels with an opportunity to test their revolutionary theories in practice. After the publication of the “Communist Manifesto,” Marx returned to Germany, where he hoped to participate in the revolution and help shape its outcome.

In Cologne, Marx re-established the Neue Rheinische Zeitung, a newspaper that advocated for democratic reforms and supported the revolutionary movement. Under Marx’s editorship, the newspaper became one of the most important voices of the radical left in Germany. Marx used the newspaper to criticize the Prussian government, the bourgeoisie, and the moderate liberal leaders who were unwilling to take decisive action against the existing political order. He argued that the bourgeois revolution had failed to address the needs of the working class and that only a proletarian revolution could achieve true social emancipation.

Despite Marx’s efforts, the revolutionary movements of 1848 were largely unsuccessful. The conservative forces in Europe, including the Prussian state, managed to suppress the uprisings and restore the old order. The failure of the revolutions led to a period of reaction, during which many radical leaders, including Marx, were forced into exile. In 1849, Marx was expelled from Prussia and fled to Paris, only to be expelled again, after which he settled in London, where he would spend the rest of his life.

In London, Marx found himself in a difficult situation. He and his family lived in poverty, often relying on the financial support of Engels, who continued to work in his family’s textile business in Manchester. Despite these hardships, Marx remained committed to his revolutionary cause. He continued to write for various radical newspapers and began work on his magnum opus, Das Kapital, a critical analysis of the capitalist mode of production.

The First International and Intellectual Legacy (1864-1872)

During his years in London, Karl Marx became increasingly involved in international socialist movements, culminating in his participation in the founding of the International Workingmen’s Association, commonly known as the First International, in 1864. The First International was a coalition of labor unions, socialists, communists, and anarchists from various countries, united in their opposition to capitalism and their desire for social reform. Marx quickly emerged as one of the leading figures within the organization, thanks to his deep theoretical insights and his reputation as a radical thinker.

The First International provided Marx with a platform to influence and direct the labor movement on a global scale. He was elected to the General Council of the organization and became its Corresponding Secretary for Germany. Marx used his position to advocate for the ideas of socialism and communism, emphasizing the need for working-class solidarity across national boundaries. He believed that the international working class had the potential to overthrow the capitalist system and establish a communist society, free from exploitation and oppression.

One of Marx’s key contributions to the First International was his critique of the Paris Commune of 1871. The Commune, which was established after the fall of Napoleon III and the collapse of the French Second Empire, was an experiment in working-class self-government. Marx saw the Commune as a harbinger of future proletarian revolutions and wrote The Civil War in France, in which he praised the Communards for their bravery and highlighted the lessons that could be drawn from their experience. Although the Commune was ultimately crushed by the French government, Marx argued that it represented a significant step forward in the struggle for workers’ emancipation.

However, the First International was not without its internal conflicts. Marx’s views often clashed with those of other prominent members, particularly the anarchists led by Mikhail Bakunin. Bakunin advocated for the immediate abolition of the state and was critical of Marx’s emphasis on political struggle and the role of a centralized party. The ideological rift between the Marxists and the anarchists eventually led to a split within the First International. At the Hague Congress in 1872, Marx and his supporters succeeded in expelling Bakunin and his followers from the organization, effectively weakening the First International, which dissolved a few years later.

Despite the challenges and setbacks, Marx’s work with the First International had a profound impact on the development of the global labor movement. His ideas on class struggle, the role of the state, and the necessity of proletarian revolution became central to socialist thought and would influence future generations of socialists, communists, and labor activists. Moreover, Marx’s participation in the First International helped to establish his reputation as one of the leading theorists of socialism, a legacy that would endure long after his death.

Writing of Das Kapital and Later Years (1867-1883)

The period from the mid-1860s to the late 1870s was marked by Karl Marx’s intense focus on his most ambitious intellectual project, Das Kapital. This work was intended as a comprehensive critique of the capitalist system, examining its economic dynamics, social consequences, and historical development. Marx devoted much of his energy to this project, despite the ongoing financial struggles and health issues that plagued him throughout his later years.

The first volume of Das Kapital was published in 1867 and received a mixed reception. While some praised Marx’s analysis of the capitalist mode of production, others criticized it for its dense and complex style. Das Kapital was not just a critique of capitalism; it was also a deeply theoretical work, grounded in Marx’s materialist conception of history and his theory of surplus value. Marx argued that the capitalist system was inherently exploitative, as the bourgeoisie, or capitalist class, extracted surplus value from the proletariat, or working class, through the process of wage labor. This exploitation, Marx contended, was the source of profit and the driving force behind capitalist accumulation.

Marx intended Das Kapital to be a multi-volume work, but he was only able to complete the first volume during his lifetime. The second and third volumes were left incomplete at his death and were later edited and published by Friedrich Engels, who compiled Marx’s notes and manuscripts. Despite this, Das Kapital became one of the most influential works in the history of political economy and laid the foundation for Marxist economics. Its analysis of capitalism’s internal contradictions and its prediction of the eventual collapse of the system under its own weight resonated with many who were critical of the social inequalities and crises inherent in capitalism.

In his later years, Marx continued to be active in political and intellectual circles, though his health began to deteriorate. He suffered from a range of ailments, including chronic bronchitis, pleurisy, and liver problems, which were exacerbated by the poor living conditions he endured for much of his life. Despite these challenges, Marx remained committed to his work and continued to correspond with socialists and labor activists from around the world, offering advice and support for various revolutionary movements.

Marx also witnessed the spread of socialist ideas during this period, with socialist and labor movements gaining ground in Europe and beyond. He was encouraged by these developments, seeing them as evidence of the growing class consciousness of the proletariat. However, he was also critical of certain tendencies within the socialist movement, particularly those that he believed deviated from the principles of scientific socialism. Marx was particularly skeptical of utopian socialists and reformists, who he felt underestimated the necessity of revolutionary struggle.

On March 14, 1883, Karl Marx passed away in London at the age of 64. He was buried in Highgate Cemetery, where his grave later became a site of pilgrimage for socialists and communists from around the world. At the time of his death, Marx was relatively unknown outside of a small circle of radicals and intellectuals, but his ideas would soon gain widespread recognition and influence, shaping the course of the 20th century and beyond.

Marx’s Influence and Legacy

Karl Marx’s influence on the world cannot be overstated. Although his ideas were not widely recognized during his lifetime, they gained significant traction in the decades following his death, particularly after the Russian Revolution of 1917, which led to the establishment of the first socialist state under the leadership of the Bolsheviks. Marx’s writings became the theoretical foundation for communist movements around the world, and his analysis of capitalism influenced countless scholars, activists, and political leaders.

Marx’s concept of historical materialism, which posits that material conditions and economic relations are the driving forces of history, became a central tenet of Marxist theory. His analysis of class struggle, which highlighted the inherent conflicts between the bourgeoisie and the proletariat, resonated with many who sought to understand the social and economic inequalities of the modern world. Moreover, Marx’s critique of capitalism, particularly his theory of surplus value and his analysis of the capitalist mode of production, provided a powerful tool for understanding the dynamics of industrial society.

In the 20th century, Marxism became the basis for the development of communist and socialist states, most notably in the Soviet Union, China, and Eastern Europe. Leaders such as Vladimir Lenin, Mao Zedong, and Fidel Castro drew heavily on Marxist theory to justify their revolutionary movements and the establishment of socialist economies. However, the implementation of Marxism in these states often diverged significantly from Marx’s original ideas, leading to debates among scholars and activists about the interpretation and application of Marxist theory.

Marx’s influence extended beyond the political realm, as his ideas also shaped the fields of sociology, economics, history, and philosophy. The Frankfurt School, a group of critical theorists associated with the Institute for Social Research in Germany, developed a form of Marxist theory that incorporated elements of psychoanalysis, cultural critique, and critical theory. In economics, Marxist analysis has continued to be a significant school of thought, offering alternative perspectives to mainstream economics and influencing debates on issues such as inequality, labor relations, and economic crises.

Despite the collapse of many communist regimes in the late 20th century, Marx’s ideas have continued to inspire new generations of activists, scholars, and political movements. The resurgence of interest in Marxism in the 21st century, particularly in the context of global capitalism’s crises, environmental degradation, and rising inequality, attests to the enduring relevance of his critique of capitalism. While Marx’s predictions about the inevitable collapse of capitalism have not come to pass in the form he envisioned, his analysis of the system’s contradictions and the impact of those contradictions on society remains a powerful tool for understanding the world today.

Critiques and Controversies

Karl Marx’s ideas have been the subject of extensive critique and controversy since they were first formulated. While many have hailed Marx as a visionary thinker who provided a radical critique of capitalism, others have criticized his ideas as overly deterministic, reductionist, or unrealistic.

One of the most common critiques of Marxism is its perceived economic determinism. Critics argue that Marx’s focus on the economic base of society and the primacy of class struggle tends to overlook the role of ideas, culture, and individual agency in shaping history. They contend that Marx’s theory reduces complex social phenomena to simple economic explanations, ignoring the influence of religion, nationalism, and other factors that have historically played significant roles in shaping societies.

Another major critique is the historical application of Marxism in practice, particularly in the form of communist regimes in the 20th century. The authoritarianism, repression, and economic failures associated with many of these regimes have led to widespread disillusionment with Marxism. Critics argue that the concentration of power in the hands of the state, as advocated by some interpretations of Marxist theory, often leads to the suppression of individual freedoms and the establishment of oppressive bureaucratic systems.

Marx’s views on revolution and the role of the proletariat have also been questioned. Some critics argue that Marx’s theory of revolution is overly optimistic in its assumption that the proletariat, as a unified class, would inevitably rise up to overthrow the bourgeoisie. They point out that Marx underestimated the capacity of the capitalist system to adapt and evolve, incorporating reforms that alleviate some of the worst conditions of the working class. Moreover, critics argue that Marx overlooked the potential for divisions within the working class itself, based on factors such as race, nationality, and gender, which can complicate the formation of a unified revolutionary movement.

Additionally, Marx’s insistence on the abolition of private property and the establishment of a classless, stateless society has been criticized as utopian and impractical. Critics argue that Marx did not provide a clear blueprint for how such a society would function, and that attempts to implement Marxist principles have often resulted in economic inefficiencies and shortages, as seen in various state socialist experiments.

Another area of controversy concerns Marx’s views on colonialism and race. While Marx was a vocal critic of imperialism and the exploitation of colonized peoples, some scholars have pointed out that his analysis often focused primarily on class relations in Europe, neglecting the complexities of race, ethnicity, and colonialism. Critics argue that Marx’s Eurocentrism limited his ability to fully understand the dynamics of imperialism and the ways in which it intersected with race and class on a global scale.

Despite these critiques, Marxism has remained a potent and influential force in global intellectual and political life. Many of Marx’s defenders argue that his work provides a powerful critique of capitalism that remains relevant in the face of ongoing economic crises, growing inequality, and environmental degradation. They contend that while Marx’s theories may need to be updated and adapted to contemporary conditions, the core insights of Marxism continue to offer valuable tools for understanding and challenging the injustices of the modern world.

In recent years, there has been a resurgence of interest in Marx’s ideas, particularly in the context of the global financial crisis of 2008 and the subsequent rise of anti-capitalist movements such as Occupy Wall Street. Scholars and activists have revisited Marx’s work to explore its relevance to contemporary issues such as globalization, neoliberalism, and climate change. This renewed interest in Marxism has led to a re-evaluation of some of the critiques and controversies surrounding Marx’s work, with many arguing that his ideas offer a critical framework for addressing the pressing challenges of the 21st century.

Marxism in the 20th Century: Revolutions and State Socialism

The 20th century witnessed the rise and fall of numerous states and movements that claimed to be inspired by Marx’s ideas. The most significant of these was the Russian Revolution of 1917, which led to the establishment of the Soviet Union, the world’s first socialist state. Led by Vladimir Lenin and the Bolsheviks, the Russian Revolution was heavily influenced by Marxist theory, particularly the idea of proletarian revolution and the dictatorship of the proletariat.

Lenin adapted Marx’s ideas to the specific conditions of Russia, a largely agrarian society with a relatively small industrial working class. He argued that the vanguard party, composed of professional revolutionaries, was necessary to lead the working class in the overthrow of the capitalist state and the establishment of socialism. This approach, known as Leninism, diverged from Marx’s original emphasis on the spontaneous uprising of the proletariat, reflecting the challenges of applying Marxist theory to different historical and social contexts.

The success of the Russian Revolution had a profound impact on the global socialist movement. The Soviet Union became a model for other revolutionary movements, inspiring the establishment of communist parties and socialist states in various parts of the world, including China, Cuba, and Eastern Europe. However, the implementation of Marxism in these states often led to significant departures from Marx’s original ideas. The concentration of power in the hands of the state, the suppression of political dissent, and the use of authoritarian methods to maintain control were all justified in the name of building socialism, but they also led to widespread human rights abuses and economic inefficiencies.

The rise of state socialism in the 20th century also sparked debates within the Marxist movement itself. Some Marxists criticized the Soviet model as a betrayal of Marxist principles, arguing that it had led to the creation of a new bureaucratic class that exploited the working class in much the same way as the capitalist class had. Others defended the Soviet Union as a necessary stage in the transition to socialism, pointing to its achievements in areas such as industrialization, education, and social welfare.

The collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991 marked a significant turning point for Marxism. The disintegration of the Soviet state and the transition to capitalism in Eastern Europe and Russia led to widespread disillusionment with Marxist theory and the decline of many communist parties around the world. However, the end of the Cold War also opened up new possibilities for rethinking and renewing Marxism in the face of changing global conditions.

In the latter half of the 20th century, Marxism also influenced various movements and intellectual traditions outside the Soviet sphere. In Latin America, Marxist ideas played a key role in revolutionary movements such as the Cuban Revolution, led by Fidel Castro and Che Guevara, and the Sandinista Revolution in Nicaragua. In Africa, Marxism influenced anti-colonial struggles and the development of post-colonial socialist states, such as those led by leaders like Kwame Nkrumah in Ghana and Julius Nyerere in Tanzania.

In the West, Marxism continued to evolve, with scholars and activists developing new interpretations of Marx’s ideas in response to contemporary social and political issues. The Frankfurt School, for example, combined Marxist theory with critical theory and psychoanalysis to analyze the cultural and ideological dimensions of capitalism. Meanwhile, in the 1960s and 1970s, the New Left emerged as a movement that sought to revitalize Marxism by addressing issues of race, gender, and environmentalism, which had been largely neglected by traditional Marxist theory.

Marxism in the 21st Century: Challenges and Renewals

In the 21st century, Marxism continues to be a relevant and contested intellectual and political tradition. The global financial crisis of 2008, which exposed the vulnerabilities and contradictions of the capitalist system, led to a renewed interest in Marx’s critique of capitalism. Scholars, activists, and politicians began to revisit Marx’s ideas, exploring how they might offer solutions to the pressing challenges of the modern world, including economic inequality, climate change, and the erosion of democratic institutions.

One of the key challenges facing Marxism in the 21st century is the need to adapt its theories to the realities of contemporary capitalism. The globalized economy, the rise of digital technology, and the increasing importance of finance and information in the production process have transformed the nature of work and class relations. Some Marxist scholars have sought to update Marx’s analysis by incorporating these new developments, exploring concepts such as cognitive capitalism, the precariat, and digital labor.

Another significant challenge is the legacy of 20th-century state socialism, which has left a complicated and often negative legacy for Marxist movements. The authoritarianism, economic failures, and human rights abuses associated with many Marxist-inspired states have led to widespread skepticism about the feasibility of Marxist ideas in practice. In response, some Marxists have sought to distance themselves from the state-centric models of socialism, advocating for more decentralized, democratic forms of socialism that emphasize workers’ self-management and direct participation in economic decision-making.

The rise of new social movements in the 21st century, such as the global justice movement, climate justice activism, and movements for racial and gender equality, has also presented both challenges and opportunities for Marxism. These movements often critique capitalism from perspectives that go beyond traditional class analysis, incorporating issues of identity, culture, and the environment. Some Marxists have engaged with these movements, seeking to integrate their insights into a broader critique of capitalism, while others have criticized them for diluting the focus on class struggle.

In recent years, there has also been a resurgence of interest in socialism as a political alternative to neoliberal capitalism. In the United States and Europe, socialist ideas have gained traction among younger generations, who are increasingly disillusioned with the inequalities and injustices of the current system. Figures such as Bernie Sanders in the United States and Jeremy Corbyn in the United Kingdom have popularized socialist policies, drawing on Marxist ideas to advocate for issues such as wealth redistribution, universal healthcare, and workers’ rights.

However, the future of Marxism in the 21st century remains uncertain. While Marx’s critique of capitalism continues to resonate with many, the challenges of developing a viable and just alternative to capitalism are significant. The experiences of the 20th century have shown that the implementation of Marxist ideas is fraught with difficulties, and the path to a post-capitalist society is likely to be complex and contested.

Despite these challenges, Marx’s legacy endures. His analysis of the contradictions of capitalism, his theory of class struggle, and his vision of a society free from exploitation continue to inspire those who seek to understand and transform the world. As new forms of capitalism emerge and new social movements take shape, Marxism remains a vital and evolving tradition, offering critical tools for analyzing the past, understanding the present, and imagining the future.