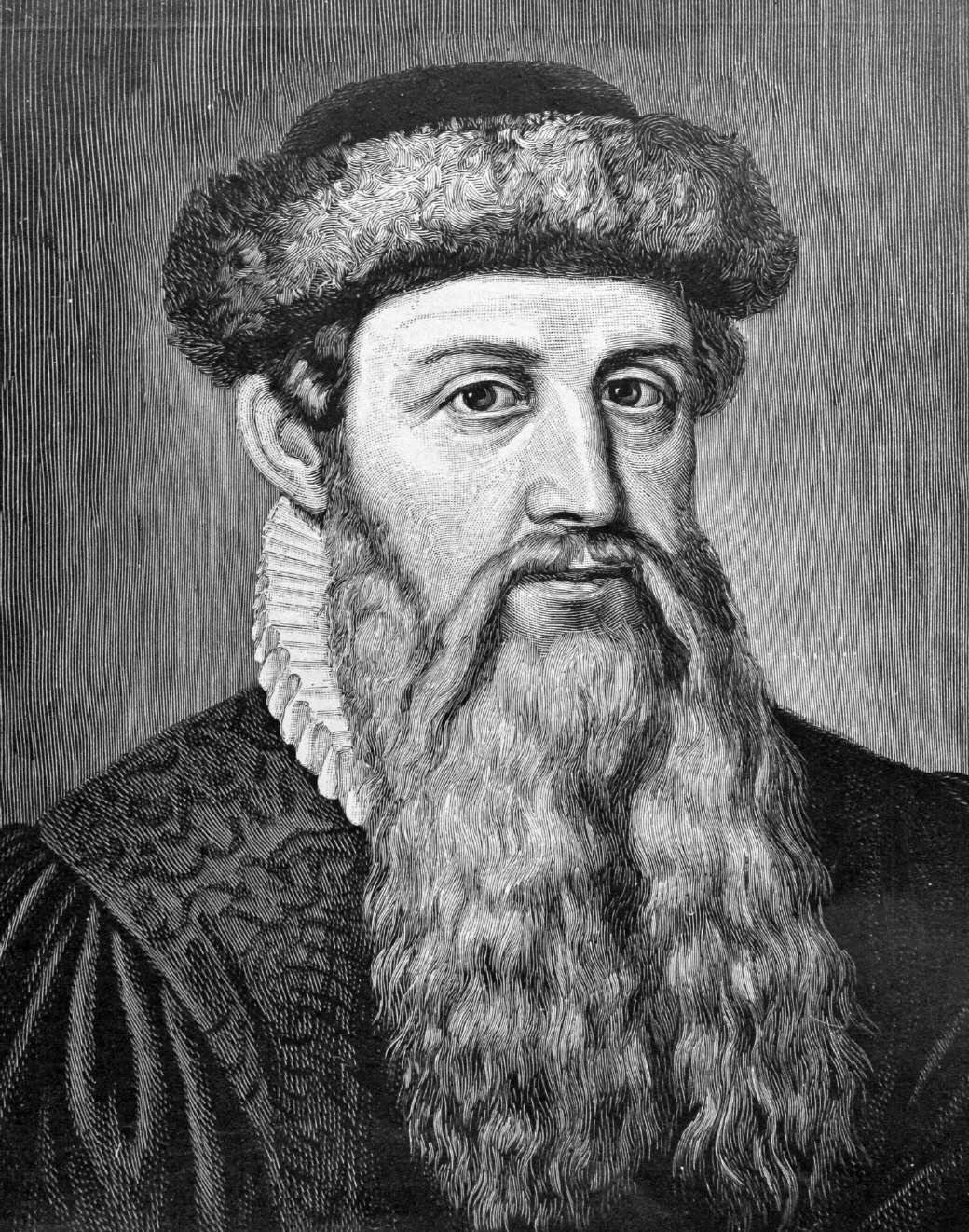

Johannes Gutenberg (c. 1400–1468) was a German inventor and printer whose introduction of movable type printing in Europe revolutionized the production of books and the spread of knowledge. His most famous work, the Gutenberg Bible, was the first major book printed using his innovative technology around 1455. Before Gutenberg’s invention, books were painstakingly copied by hand, making them rare and expensive. His printing press made it possible to produce books quickly, accurately, and in large quantities, dramatically lowering their cost and making literature and scholarly works accessible to a much broader audience. This innovation played a key role in the spread of ideas during the Renaissance, the Reformation, and the Scientific Revolution, profoundly influencing the course of Western history. Gutenberg’s work laid the foundation for the modern age of information, earning him recognition as one of the most influential figures in human history.

Early Life and Background

Johannes Gutenberg, born around 1400 in Mainz, Germany, was a pivotal figure in history, best known for his invention of the printing press with movable type. His early life remains somewhat obscure, but it’s believed he was born into a family of patricians, the upper class of the time. His father, Friele Gensfleisch zur Laden, was a merchant, and his mother, Else Wyrich, came from a wealthy family. The family adopted the surname “Gutenberg,” derived from the name of their residence.

Growing up in such a household, Gutenberg likely received a solid education, which was typical for children of the patrician class. Mainz, a city with a rich cultural and commercial background, would have exposed him to a variety of ideas, including those related to technology and craftsmanship. Although little is known about his childhood, it is widely believed that Gutenberg was introduced to the craft of metalworking and engraving, skills that would later prove crucial in his inventions.

The political climate of the time in Mainz was turbulent, with frequent power struggles between the patricians and the guilds. In the early 1420s, these conflicts reached a peak, resulting in the exile of many patrician families, including the Gutenbergs. This forced relocation took Gutenberg to Strasbourg, where he would live for nearly two decades. It was in Strasbourg that Gutenberg honed his skills and developed the ideas that would lead to one of history’s most significant inventions.

During his time in Strasbourg, Gutenberg became involved in various business ventures. He worked as a goldsmith, where he perfected his metalworking skills, and as a mirror maker. The latter profession was significant because it involved the production of polished metal mirrors used by pilgrims to capture holy light, an industry that required precision and skill. These early experiences in metalworking and crafting would later contribute to the development of his printing press.

Gutenberg’s time in Strasbourg was marked by experimentation and innovation. He began to explore the possibility of automating the process of bookmaking, which was laborious and time-consuming. The idea of creating a machine that could replicate text quickly and efficiently was revolutionary and laid the foundation for his future work in printing. By combining his knowledge of metalworking with his interest in typography, Gutenberg began to conceptualize the movable type printing press.

The Invention of the Printing Press

Gutenberg’s invention of the printing press with movable type in the mid-15th century is often heralded as one of the most significant technological advancements in human history. Before this invention, books were laboriously copied by hand, usually by monks in monasteries. This process was time-consuming, expensive, and prone to errors, which meant that books were scarce and available only to the wealthy or to religious institutions. Gutenberg’s invention democratized knowledge by making it possible to produce books quickly, efficiently, and at a fraction of the previous cost.

The key to Gutenberg’s innovation was his development of movable type. Unlike previous methods that used entire blocks of text, Gutenberg’s press used individual letters cast in metal that could be arranged and rearranged to form words, sentences, and pages. This method was not only more flexible but also more durable and precise. Gutenberg’s background in metalworking was crucial here, as he was able to create letters that were uniform in size and shape, ensuring a consistent print quality.

Gutenberg also developed an oil-based ink that was more durable and adhered better to metal type than the water-based inks previously used in hand copying. Additionally, he designed a wooden press, adapted from the screw presses used in winemaking, that could apply even pressure across a flat surface. This press allowed for the efficient transfer of ink from the type to the paper, producing clear and consistent impressions.

By 1450, Gutenberg had a working press and was producing printed materials. His first major project was the printing of indulgences for the Catholic Church, a task that provided him with the funds necessary to continue his work. Indulgences, which were essentially certificates sold by the Church to absolve individuals of sin, were in high demand and provided a steady stream of income for Gutenberg.

However, it was the printing of the Bible that would cement Gutenberg’s place in history. The Gutenberg Bible, also known as the 42-line Bible, was printed around 1455 and is considered the first major book printed using movable type. The Bible was a massive undertaking, requiring an estimated 180 copies to be printed, each consisting of over 1,200 pages. The precision and craftsmanship of the Gutenberg Bible were extraordinary, with many copies featuring hand-illuminated decorations that blended the new technology of printing with traditional manuscript artistry.

The impact of Gutenberg’s printing press was immediate and profound. For the first time in history, it was possible to produce books on a large scale, making knowledge more accessible to a broader audience. This innovation laid the groundwork for the spread of literacy, the Renaissance, the Reformation, and the Scientific Revolution. Gutenberg’s press did not just change the way books were made; it changed the world.

The Gutenberg Bible

The Gutenberg Bible, also known as the 42-line Bible, is one of the most famous books in history, not only for its religious significance but also for its role as the first major book produced using Johannes Gutenberg’s revolutionary movable type printing press. Printed around 1455, the Gutenberg Bible marked the beginning of the “Gutenberg Revolution” and the spread of printed books across Europe and the world.

The production of the Gutenberg Bible was an enormous undertaking that required meticulous planning, technical skill, and significant resources. The Bible was printed in Latin, the scholarly and ecclesiastical language of the time, and consisted of the Vulgate text, which was the standard version of the Bible used by the Catholic Church. Each copy of the Gutenberg Bible comprised two volumes, with a total of 1,286 pages. The name “42-line Bible” comes from the fact that each page contained 42 lines of text, arranged in two columns.

One of the most remarkable aspects of the Gutenberg Bible is its aesthetic quality. Gutenberg went to great lengths to ensure that his printed Bible would rival the beauty of hand-copied manuscripts. The typeface he used was designed to mimic the Gothic script commonly used in manuscript Bibles of the time. This typeface, known as Textura, was characterized by its dense, angular, and black-letter appearance, which gave the printed text a similar visual weight to the hand-written script.

In addition to the typeface, many copies of the Gutenberg Bible were hand-illuminated, with decorative initials and marginal illustrations added by skilled artists after the text was printed. This combination of printed text and hand-drawn decoration created a bridge between the old and new methods of book production, allowing Gutenberg’s Bible to be both a technical marvel and a work of art.

The printing of the Gutenberg Bible required a significant amount of resources, including paper, ink, and skilled labor. It is estimated that Gutenberg produced around 180 copies of the Bible, with about 150 on paper and 30 on vellum, a fine parchment made from animal skins. The paper used was of the highest quality, imported from Italy, and the ink was specially formulated to adhere to the metal type and produce a rich, black print.

The Gutenberg Bible was not only a technical achievement but also a commercial one. While it was expensive to produce, it was still more affordable than hand-copied Bibles, making it accessible to a broader audience, including wealthy individuals, monasteries, and universities. The success of the Gutenberg Bible demonstrated the commercial potential of the printing press and encouraged the spread of printing technology across Europe.

Today, only 49 copies of the Gutenberg Bible are known to exist, with some in complete form and others in fragments. These surviving copies are among the most prized possessions of libraries and museums around the world. The Gutenberg Bible is more than just a religious text; it is a symbol of the transformative power of the printed word and a testament to Johannes Gutenberg’s ingenuity and vision.

Impact on Society and Culture

The invention of the printing press by Johannes Gutenberg had a profound and far-reaching impact on society and culture, setting the stage for major developments in education, religion, science, and the arts. The ability to produce books and other printed materials quickly and in large quantities revolutionized the way information was disseminated and consumed, leading to significant changes in nearly every aspect of life.

One of the most immediate effects of the printing press was the democratization of knowledge. Before Gutenberg’s invention, books were rare and expensive, accessible only to the wealthy or to institutions like monasteries and universities. The printing press made books more affordable and widely available, which in turn led to an increase in literacy rates across Europe. As more people learned to read, they gained access to a wealth of information and ideas that had previously been out of reach.

This increased access to information had a profound impact on education. Universities and schools were able to produce textbooks more efficiently, and scholars could share their work with a wider audience. The standardization of texts through printing also meant that knowledge could be more consistently transmitted from one generation to the next. This played a crucial role in the spread of Renaissance humanism, as the works of classical authors, as well as contemporary scholars, were more widely distributed and studied.

The printing press also had a significant impact on religion, particularly in the context of the Protestant Reformation. Martin Luther, a key figure in the Reformation, famously utilized the printing press to disseminate his 95 Theses and other writings, challenging the practices of the Catholic Church. The ability to print and distribute religious texts, including vernacular translations of the Bible, allowed Reformation ideas to spread rapidly and widely, contributing to the fragmentation of the Catholic Church and the rise of Protestant denominations.

In addition to its impact on education and religion, the printing press also revolutionized the dissemination of scientific knowledge. Before the advent of printing, scientific knowledge was often confined to small circles of scholars who corresponded with each other or shared handwritten manuscripts. The printing press enabled the rapid and widespread distribution of scientific texts, which facilitated collaboration and the sharing of discoveries across Europe. This was a key factor in the Scientific Revolution of the 16th and 17th centuries, as scientists like Copernicus, Galileo, and Newton could publish their findings and ideas more easily, thereby challenging established beliefs and advancing the frontiers of knowledge.

The printing press also played a crucial role in the standardization of language and the development of national cultures. Before printing, regional dialects and spelling variations were common, but the widespread distribution of printed materials helped to standardize languages. For example, the publication of the King James Bible in 1611 had a significant impact on the standardization of the English language. Similarly, printed works in other vernacular languages contributed to the development of national literatures and a sense of shared cultural identity.

The arts were also profoundly affected by the printing press. The availability of printed music, for instance, allowed composers to distribute their works more widely, leading to a flourishing of musical creativity during the Renaissance and Baroque periods. The press also facilitated the spread of visual art, as engravings and woodcuts could be reproduced and disseminated alongside texts, making art more accessible to the public.

Moreover, the printing press played a role in the development of the modern concept of authorship and intellectual property. Before the advent of printing, the reproduction of texts was largely controlled by religious institutions, and authors often remained anonymous. With the ability to mass-produce books, authors began to gain recognition for their work, and the idea of copyright emerged as a way to protect their intellectual property.

The social and cultural impact of the printing press was not without its challenges. The rapid spread of information also led to the spread of misinformation and propaganda. Political and religious authorities were quick to recognize the power of the printed word, and many sought to control or censor printed materials to maintain their influence. The Catholic Church, for example, established the Index Librorum Prohibitorum, a list of prohibited books, in an effort to suppress the spread of ideas it deemed heretical.

Despite these challenges, the printing press undeniably transformed society. It facilitated the exchange of ideas, fostered education and literacy, and contributed to the development of modern science, religion, and culture. Johannes Gutenberg’s invention was a catalyst for change that helped shape the modern world, and its legacy can still be felt today in the ongoing importance of print and the written word.

Challenges and Controversies

Johannes Gutenberg’s journey to inventing the printing press was not without its share of challenges and controversies. The process of developing the press and bringing his vision to fruition was fraught with financial difficulties, legal battles, and personal setbacks. These challenges not only tested Gutenberg’s resolve but also highlighted the complexities of pioneering a technology that would change the world.

One of the major challenges Gutenberg faced was securing the necessary funding to develop his printing press. As an inventor, he needed significant financial resources to purchase materials, hire skilled workers, and sustain the lengthy process of experimentation and refinement. Gutenberg turned to several investors to fund his project, the most notable being Johann Fust, a wealthy merchant from Mainz. In 1450, Fust lent Gutenberg 800 guilders, a substantial sum at the time, to continue his work on the press. This partnership, however, would later lead to significant legal disputes.

In 1452, Fust provided Gutenberg with an additional loan of 800 guilders, under the condition that it would be repaid with interest. However, as the printing press project continued to require more resources, Gutenberg struggled to meet the repayment terms. By 1455, the relationship between Gutenberg and Fust had soured, leading Fust to file a lawsuit against Gutenberg for the repayment of the loans. The court ruled in Fust’s favor, and as a result, Gutenberg was forced to relinquish control of his printing workshop, including the press and the unfinished Bibles, to Fust.

This legal battle was a devastating blow to Gutenberg, who lost not only his printing equipment but also the potential profits from the sale of the Gutenberg Bible. Fust, along with Peter Schöffer, Gutenberg’s former assistant, took over the printing operation and completed the production of the Bibles. While Fust and Schöffer went on to become successful printers, Gutenberg’s role in the completion of the Bible and the invention of the press was overshadowed by the legal dispute.

Despite losing his printing workshop, Gutenberg did not abandon his work. He continued to be involved in the printing business, albeit on a smaller scale. In 1465, he was awarded a pension by Archbishop Adolph von Nassau, which provided him with a modest income and recognition for his contributions. This pension allowed Gutenberg to live comfortably in his later years, but it was a far cry from the wealth and success he might have achieved had he retained control of his printing press.

The controversies surrounding Gutenberg’s invention also extend to the question of authorship and credit. While Gutenberg is widely recognized as the father of modern printing, the contributions of other figures, such as Johann Fust and Peter Schöffer, have sometimes complicated the narrative. Some historians argue that Fust and Schöffer played a significant role in refining and commercializing the printing process, and therefore, should share in the credit for the invention. Others maintain that Gutenberg’s initial vision and technical innovations were the foundation upon which the success of the printing press was built.

Another controversy relates to the issue of intellectual property. In the early days of printing, the concept of intellectual property was not well established, and printers often copied each other’s work without attribution or compensation. Gutenberg himself may have drawn on existing technologies, such as the screw press and movable type used in China and Korea, in developing his press. The lack of clear intellectual property laws meant that Gutenberg’s ideas could be replicated by others, sometimes to his detriment.

Despite these challenges and controversies, Gutenberg’s legacy as the inventor of the printing press remains secure. His determination to overcome financial difficulties, legal battles, and personal setbacks underscores the resilience and vision that drove him to create a technology that would change the course of history.

The biography of Johannes Gutenberg provided earlier does not explicitly mention his death. Here is an additional section focusing on the final years of his life and his death:

Final Years and Death

Johannes Gutenberg spent the later years of his life in relative obscurity, despite the monumental impact of his invention. After the legal disputes with Johann Fust, Gutenberg’s financial situation remained difficult. He was forced to give up his printing workshop and the potential profits from his most famous project, the Gutenberg Bible. However, he did not give up his work in printing.

In 1465, three years before his death, Gutenberg received some recognition for his contributions when Archbishop Adolph von Nassau of Mainz awarded him a pension. This pension, which included a yearly allowance of grain, wine, and clothing, was a modest acknowledgment of Gutenberg’s achievements and provided him with some financial stability in his final years.

Little is known about Gutenberg’s personal life during these years, as he seems to have lived quietly, continuing his work in a smaller capacity. The exact nature of his activities during this period is not well-documented, but it is believed that he remained involved in the printing industry, likely assisting other printers or working on smaller projects.

Johannes Gutenberg passed away on February 3, 1468, in Mainz, Germany. At the time of his death, his revolutionary invention had already begun to spread throughout Europe, although Gutenberg himself did not live to see the full extent of its impact. His death went largely unnoticed outside of his local community, and he was buried in the Franciscan church in Mainz. Unfortunately, the church and his grave were later destroyed, and no physical marker of his final resting place remains.

Despite the lack of recognition at the time of his death, Gutenberg’s legacy would soon become apparent as the printing press revolutionized communication, education, and culture across the world. Today, Johannes Gutenberg is remembered as one of history’s most influential figures, whose invention laid the foundation for the modern era of information and knowledge dissemination.

Legacy and Influence

Johannes Gutenberg’s legacy is one of profound and lasting influence, not only in the field of printing but also in the broader scope of human history. His invention of the printing press with movable type is often regarded as one of the most important developments in the second millennium, a transformative technology that reshaped society in ways that are still felt today.

The most immediate and enduring impact of Gutenberg’s invention was the democratization of knowledge. By making books and other printed materials more accessible and affordable, the printing press broke down the barriers that had previously limited the spread of information to a small elite. This democratization played a crucial role in the intellectual and cultural developments of the Renaissance, as it allowed the ideas of scholars, artists, and scientists to reach a wider audience. The printing press also facilitated the spread of religious and philosophical ideas, contributing to movements like the Protestant Reformation and the Enlightenment.

Gutenberg’s press laid the foundation for the modern publishing industry. The ability to mass-produce books, newspapers, pamphlets, and other printed materials revolutionized the way people communicated and shared information. The rise of print culture led to the development of new forms of literature, journalism, and advertising, all of which continue to shape our world today. The press also played a key role in the standardization of languages and the development of national literatures, helping to foster a sense of shared cultural identity among people who spoke the same language.

In the realm of science and education, Gutenberg’s invention was a catalyst for progress. The ability to print and distribute scientific texts and treatises allowed for the rapid dissemination of new ideas and discoveries, which in turn accelerated the pace of scientific advancement. The printing press also transformed education by making textbooks more widely available and affordable, leading to higher literacy rates and a more educated populace.

Gutenberg’s influence extended beyond the Western world. The printing press was quickly adopted in other parts of the world, including the Middle East, Asia, and the Americas, where it played a similar role in spreading knowledge and fostering cultural exchange. In many ways, Gutenberg’s invention helped to create the interconnected global society we live in today.

In recognition of his contributions, Johannes Gutenberg has been honored in numerous ways. His name is synonymous with the invention of printing, and he is often referred to as the “father of modern printing.” In 1999, the A&E Network named Gutenberg the most influential person of the second millennium, highlighting the profound impact of his work on the course of history. Additionally, the Gutenberg Museum in Mainz, Germany, stands as a testament to his legacy, preserving and showcasing the history of printing and its evolution.

Gutenberg’s legacy also lives on in the digital age. The advent of the internet and digital publishing can be seen as a continuation of the revolution that Gutenberg began with his printing press. Just as Gutenberg’s invention made information more accessible, the internet has further expanded the reach of knowledge, allowing people around the world to share and access information instantly. The digital age has also brought new challenges and opportunities in the realm of intellectual property, echoing some of the issues Gutenberg faced in his time.