Among the countless gods of Greek mythology, few shine as brilliantly or as multifaceted as Apollo. Known as the god of the sun, music, poetry, prophecy, and healing, Apollo stands as a figure of dazzling complexity. He was celebrated as the embodiment of beauty, harmony, and youthful vitality, yet he could also be harsh, destructive, and merciless. To the Greeks, Apollo was not merely another Olympian deity but a living symbol of the eternal tension between order and chaos, light and darkness, healing and plague.

Apollo was born of Zeus, the mighty king of the gods, and Leto, a Titaness whose grace and endurance were tested before she could deliver her children. His twin sister Artemis, goddess of the hunt and the moon, shared his celestial nature but embodied a wilder, more untamed aspect of divinity. Together, Apollo and Artemis represented two halves of the natural world: the luminous sun and the silvery moon, civilization and wilderness, music and silence, prophecy and instinct.

The Greeks revered Apollo as a god who was close to human ideals yet beyond mortal grasp. He was young but eternal, beautiful yet dangerous, inspiring yet fearsome. In him, the Greeks saw their deepest yearnings for knowledge, beauty, balance, and divine order.

The Birth of a God

Apollo’s birth itself is one of the most dramatic myths of Greek mythology. His mother, Leto, was pursued by the wrath of Hera, queen of the gods, who was enraged by Zeus’s unfaithfulness. As a result, Hera forbade any land to shelter Leto, leaving the pregnant goddess to wander endlessly in search of a safe place to give birth.

Finally, the barren, floating island of Delos offered refuge. There, amidst hardship and divine opposition, Leto gave birth to her radiant twins. Artemis was born first, helping her mother deliver her brother. Then came Apollo, bathed in light and destined to shine eternally over the world. The moment he was born, the island of Delos blossomed with golden light, flowers, and music—a sign of the god’s brilliance and future dominion.

This myth of birth on a once-desolate island carried deep symbolic meaning. Apollo was a god who transformed barrenness into abundance, chaos into order, and silence into song. Delos became one of the most sacred sites of Greece, and Apollo’s birth there was celebrated as a turning point in the divine order of the cosmos.

Apollo the Archer and Slayer of Serpents

Though Apollo is most often remembered as a god of beauty and music, his early myths emphasize his destructive power. His first great feat after birth was to slay the monstrous serpent Python, a primordial creature that guarded the sacred oracle at Delphi. Python was a symbol of ancient, chaotic powers of the earth—serpentine, dangerous, and deeply tied to the dark forces of fate.

Apollo, armed with his golden bow and arrows, challenged Python and defeated the beast. With this victory, he claimed the oracle of Delphi as his own, establishing himself as the god of prophecy and divine truth. The slaying of Python symbolized the triumph of order over chaos, of reason over primal instinct, and of light over shadow.

Yet Apollo was not only a slayer of monsters—he was also known to unleash plagues upon mortals when angered. In Homer’s Iliad, Apollo strikes the Greek army with disease after his priest, Chryses, is insulted by Agamemnon. His arrows of plague brought swift suffering, reminding mortals that Apollo’s radiant beauty could easily turn into destructive wrath.

Lord of Prophecy and the Oracle at Delphi

Perhaps no aspect of Apollo was more revered in the ancient world than his role as god of prophecy. After slaying Python, Apollo established his great temple at Delphi, where the famous oracle, the Pythia, delivered cryptic messages inspired by the god. Kings, generals, and ordinary citizens alike traveled from across Greece and beyond to consult the oracle before making decisions.

The Pythia, a priestess seated upon a tripod within the temple, would enter a trance induced by vapors rising from the earth. Her utterances, often mysterious and ambiguous, were believed to be Apollo’s words. These oracles shaped Greek history, influencing wars, colonization, and politics.

Apollo’s association with prophecy was deeply symbolic. He represented not just foresight of events but the search for higher truth and wisdom. His oracle was both a gift and a challenge—it gave glimpses of divine knowledge but in riddles that mortals had to interpret carefully. Through Delphi, Apollo became not only a god of light but also of hidden truths, guiding humanity toward deeper understanding while testing their wisdom.

Apollo and the Music of the Spheres

Apollo’s most enchanting and enduring image is as the god of music. Often depicted with a golden lyre given to him by Hermes, Apollo was believed to play melodies that resonated with the harmony of the cosmos itself. His music was not merely entertainment—it was an expression of divine order and balance.

The Greeks believed in the concept of the “music of the spheres,” the idea that the movements of the heavens created a kind of perfect, inaudible harmony. Apollo, as god of music, embodied this cosmic order. His melodies were said to soothe hearts, heal souls, and inspire poets and artists.

He presided over the Muses, the goddesses of art, poetry, history, and science, guiding their work and granting inspiration to mortals. Festivals in his honor often included musical competitions, where bards and musicians sought to channel Apollo’s spirit.

Yet Apollo’s music also carried a sharp edge. In myths where mortals dared to challenge him musically, such as Marsyas the satyr or King Midas, Apollo’s victories were merciless. When Marsyas boasted that he could outplay the god on his flute, Apollo not only defeated him but flayed him alive as punishment for hubris. The lesson was clear: divine beauty and harmony could not be rivaled by mortals.

Apollo and Healing: Light as Medicine

Another vital aspect of Apollo was his connection to health and healing. Known as a bringer of plague, he was equally celebrated as a god of medicine and recovery. His son, Asclepius, became the god of healing and medicine, worshipped in temples across Greece where the sick sought cures through dreams and rituals.

Apollo’s dual nature as both healer and destroyer reflected the Greeks’ understanding of balance in life. Just as sunlight can both nourish crops and scorch the earth, Apollo’s power could bring either health or suffering. His worshippers often invoked him to ward off epidemics and to guide physicians in their work.

In this way, Apollo was not only a celestial god but also one deeply tied to human survival. His presence lingered in the hope for recovery and in the art of medicine, which blended science and spirituality in the ancient world.

Apollo’s Love Affairs: Beauty and Tragedy

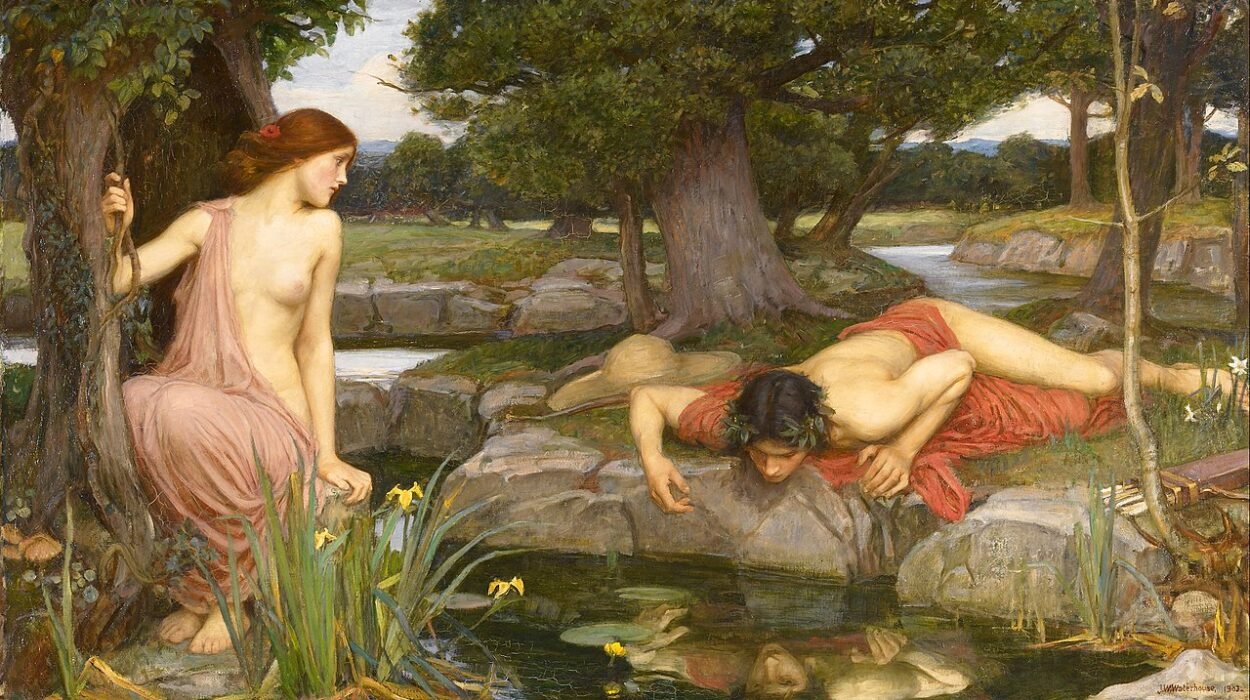

Like many gods, Apollo’s myths are filled with tales of love—yet unlike others, his stories often end in heartbreak. His pursuit of mortal women, nymphs, and even young men rarely brought him happiness, and more often led to sorrow, transformation, or tragedy.

One of the most famous tales is that of Daphne, a river nymph who fled Apollo’s advances. Desperate to escape, she prayed to her father, a river god, who transformed her into a laurel tree. Heartbroken, Apollo declared the laurel sacred, wearing its leaves as a crown in remembrance of his lost love.

Another tragic story is that of Hyacinthus, a beautiful Spartan youth whom Apollo loved dearly. While the two played a game of discus, the wind god Zephyrus, jealous of their bond, blew the discus off course, striking and killing Hyacinthus. From his blood sprang the hyacinth flower, forever commemorating Apollo’s grief.

These myths painted Apollo as a figure of longing and unfulfilled desire, whose perfection and brilliance could never fully connect with mortal love. They revealed his deeply human side—capable of passion, jealousy, and sorrow.

Apollo and the Balance of Civilization

Apollo was more than just a personal god of prophecy, music, and healing—he was also a cultural symbol of civilization itself. Where Dionysus represented wild passion, ecstasy, and chaos, Apollo stood for clarity, rationality, order, and restraint. The tension between these two gods became a central theme in Greek thought and later in philosophy, art, and literature.

Apollo represented the structured beauty of architecture, the measured rhythms of poetry, the discipline of medicine, and the harmony of music. He was the guiding light of logic and reason, qualities that the Greeks deeply valued as the foundation of their society. Yet his myths also warned that too much Apollonian order without balance could become harsh and destructive. The Greeks saw in Apollo both the promise of civilization and the danger of divine pride.

The Radiance of Apollo Beyond Greece

Apollo’s influence did not end with the fall of Greek civilization. His image and myths were adopted by the Romans, who revered him as one of their most important gods. In Roman times, he retained his roles as a healer, musician, and prophet, and his worship spread throughout the empire.

Later, during the Renaissance, Apollo became a symbol of beauty, enlightenment, and artistic inspiration. Painters, poets, and musicians depicted him as the embodiment of divine creativity. His image as the radiant archer and lyre-player echoed through centuries of European art, symbolizing the eternal pursuit of knowledge, balance, and perfection.

Even today, Apollo’s name endures—in literature, in art, and even in science. The American space program that first carried humans to the moon was named “Apollo,” linking the ancient god of light and prophecy to humanity’s bold leap into the heavens.

The Eternal God of Light

Apollo remains one of mythology’s most enduring figures because he embodies so many of humanity’s deepest longings. He is the radiant god who shines with beauty and youth, yet his arrows bring sudden death. He is the divine musician whose lyre fills the cosmos with harmony, yet he punishes those who challenge his art. He is the healer who brings relief, yet also the bringer of plague. He is the prophet who reveals divine truths, yet in riddles that test human wisdom.

In Apollo, the Greeks recognized the paradox of life itself: the balance of joy and sorrow, order and chaos, health and sickness, creation and destruction. He was not a one-dimensional god but a reflection of the complexity of existence.

To study Apollo is to step into the heart of Greek mythology and into the eternal dance of light and shadow. He remains, even now, a symbol of the radiant beauty and perilous power of the divine.

In the myths of Apollo, humanity has always found both guidance and warning, inspiration and fear. And perhaps that is why he has never truly faded from memory. For Apollo is not just a god of the Greeks—he is the eternal sun that shines on all who seek beauty, truth, and the mysteries of existence.