In a remarkable find that bridges archaeology with the chemistry of color, researchers have uncovered what is now believed to be the long-sought industrial center for the production of one of the ancient world’s most prized substances—Tyrian purple dye. This vibrant and luxurious pigment, once worn by kings, emperors, and high priests, had long been associated with mystery. For centuries, scholars had theorized that such a rare and widely distributed dye must have come from a major manufacturing hub. But despite decades of excavation and speculation, its location had remained hidden—until now.

The discovery, detailed in the journal PLOS ONE, was made at the ancient site of Tel Shiqmona, a coastal village near modern-day Haifa in Israel. Known in antiquity as a humble fishing settlement, Tel Shiqmona has suddenly emerged as a place of profound historical and cultural significance. Among the rocky remains of the old village, archaeologists unearthed striking physical evidence of a full-fledged industrial dye workshop: massive vats stained in deep purples, remnants of dye-smeared tools, and a staggering 176 artifacts directly linked to the production of Tyrian purple.

Tyrian purple is no ordinary color. In the ancient world, it was more than just a hue—it was a symbol of power, wealth, and exclusivity. So rare and labor-intensive was its production that garments dyed in Tyrian purple were often worth more than their weight in gold. Royal edicts in the Roman Empire famously forbade anyone but the emperor from wearing it. But the dye’s source is as humble as its symbolism is grand: mucus secreted by certain species of sea snails, particularly the Murex genus. These marine mollusks produce a defensive fluid that is pale yellowish-green when extracted, but transforms into a rich purple upon exposure to air and sunlight—a kind of natural alchemy that enchanted ancient dyers and rulers alike.

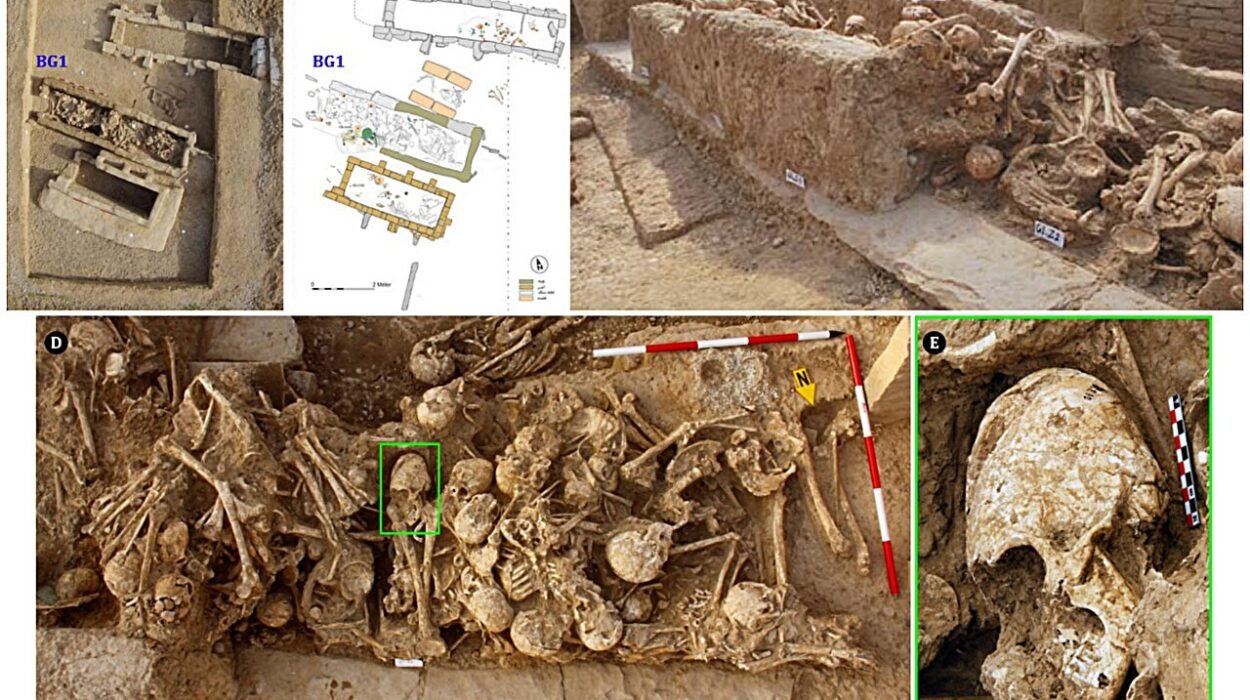

The Tel Shiqmona discovery reveals more than just a clue about the dye’s origin; it paints a vivid picture of early chemical engineering. The vats discovered on-site are particularly telling. Some could hold as much as 350 liters of fluid, indicating large-scale production. Each vat would have served as a stage in the elaborate, multi-step process required to convert the snail secretion into a stable dye that could bond with textiles. This wasn’t a matter of simply soaking fabrics in a colored liquid—making Tyrian purple involved complex chemical treatments to ensure the dye didn’t wash out or fade. Workers would have needed to maintain precise control over pH levels, exposure to sunlight, and the timing of each step.

The presence of so many dye-stained tools and other production equipment underscores how advanced the operation was. Far from being a backyard affair, this was industrial-scale craftsmanship thousands of years before the industrial revolution. Archaeologists estimate that the dyeing facility was operational for much of the Iron Age, starting around 1000 BCE. The site’s development appears to reflect the rise and fall of regional powers. Initially, it seems the facility operated on a small scale, likely supplying local elites. But as the Kingdom of Israel expanded and grew more affluent, demand for the royal dye exploded—and so too did production.

Interestingly, the research team found evidence that dye production waned following the fall of the Kingdom of Israel. But the story doesn’t end there. After the region came under Assyrian control, the dye industry seems to have seen a revival, possibly due to the Assyrians recognizing the commercial and symbolic value of Tyrian purple. This pattern of growth, decline, and resurgence ties the story of the dye to the shifting fortunes of empires, offering a colorful lens through which to view the political and economic tides of the ancient Near East.

Beyond its immediate archaeological significance, the Tel Shiqmona discovery adds a crucial dimension to our understanding of ancient economies and technologies. Tyrian purple was not just a fashion statement—it was a political tool and an economic driver. Controlling its production meant controlling a key element of prestige and power. The workshop at Tel Shiqmona may have been a state-sponsored facility, overseen by administrators who regulated output and protected trade secrets. The dye’s value was so high that rival kingdoms and empires sometimes waged diplomatic or even military campaigns to secure their own access to the precious pigment.

The chemical transformation that lies at the heart of Tyrian purple’s mystique also makes this discovery a treasure trove for the history of science. Long before modern chemistry was formally recognized as a discipline, these ancient artisans had stumbled upon a complex molecular reaction and refined it into a repeatable industrial process. The oxidization of snail secretions into a stable purple dye required a level of empirical knowledge that modern chemists still admire. Even today, recreating Tyrian purple authentically is a challenge, involving not only the extraction of the snail’s mucus but also the management of volatile reactions and prolonged exposure to sunlight to catalyze the transformation.

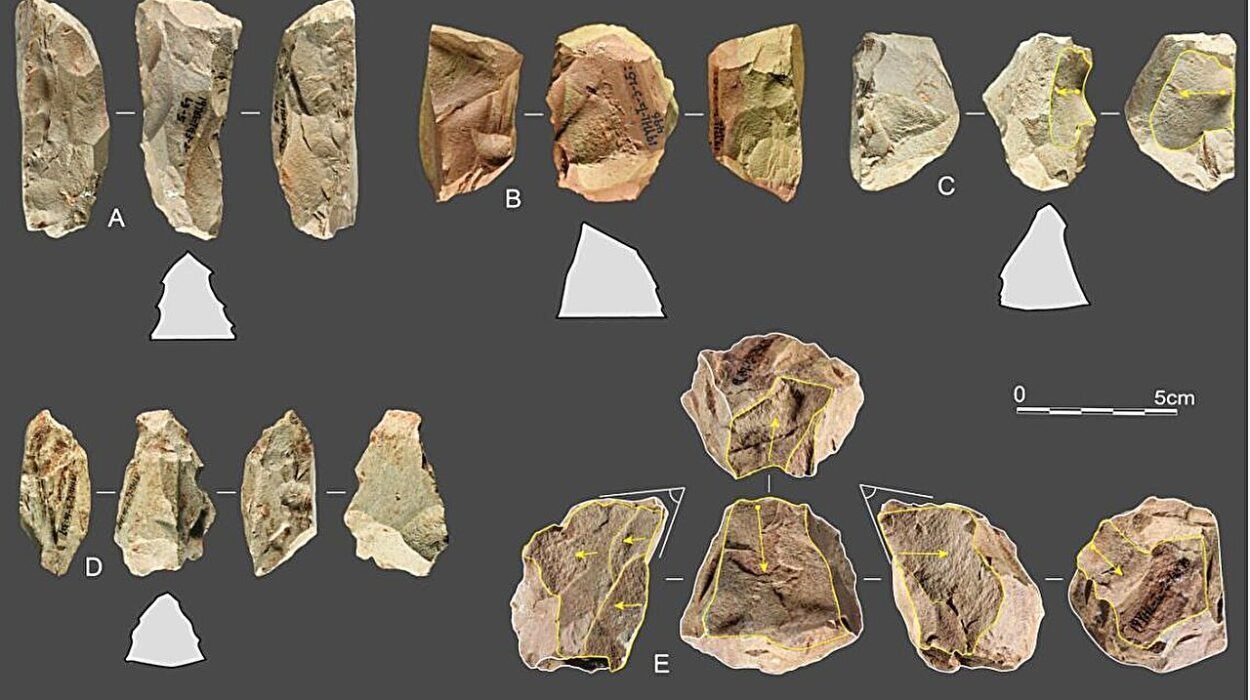

The sheer number of production tools found at the site points to a highly organized operation. These included stone basins, ceramic containers, drainage channels, and implements likely used for stirring, filtering, or heating the dye. Archaeologists also uncovered piles of crushed snail shells—evidence of the raw material in use. To create even a single gram of dye, thousands of snails had to be harvested, cracked open, and drained. The environmental impact of this industry must have been significant. The coastal location of Tel Shiqmona was ideal for such a resource-intensive process. The proximity to the sea made it easy to collect snails, and the Mediterranean climate provided the sunshine necessary for dye activation.

One particularly fascinating detail lies in the purple stains themselves. Chemical analysis of residue inside the vats confirmed the presence of brominated indigo compounds, the key component of true Tyrian purple. This not only validates the site’s function but also establishes Tel Shiqmona as one of the earliest known large-scale production sites of this legendary dye. Until now, the actual evidence of industrial Tyrian purple production had been scant, and while other sites had shown hints—broken shells, colored fragments—none had provided such conclusive and large-scale proof.

The implications of the Tel Shiqmona find ripple far beyond the world of ancient textiles. It reframes historical narratives about trade, technology, and the relationship between fashion and political authority. The dye wasn’t just traded as a finished product; it was part of a broader economic network that included raw materials, skilled labor, technological innovation, and elite consumption. It also highlights the role of coastal villages like Tel Shiqmona, previously overlooked, as critical nodes in this ancient supply chain. What might have seemed a sleepy fishing town now emerges as a center of technological ingenuity and luxury goods production.

The Tel Shiqmona discovery also opens the door for further research into ancient color technologies. Were there other such factories along the Mediterranean that simply haven’t been found yet? How did knowledge of this dyeing process spread across cultures—from the Phoenicians to the Greeks to the Romans? Could there have been secret recipes or guarded trade practices, much like the later Venetian control over glassmaking or the Chinese monopoly on silk?

And what of the workers themselves? The people who spent their days harvesting sea snails, managing stinking vats of fermenting dye, and perfecting the delicate balance of chemistry required to turn slime into splendor? While we may never know their names, the fingerprints they left on the ancient tools, and now on history itself, suggest a legacy of expertise and resilience. They were artists, chemists, and laborers all in one, transforming nature into status and color into power.

In the end, the Tel Shiqmona dye workshop is more than just an archaeological site—it is a portal into the world of ancient innovation. It shows us how people, long before the rise of modern science, harnessed biology and chemistry to create something extraordinary. It reminds us that technology doesn’t always come with wires and screens. Sometimes, it comes in the form of crushed shells, sunlit vats, and a vision for a color that could define an empire.

More information: Golan Shalvi et al, Tel Shiqmona during the Iron Age: A first glimpse into an ancient Mediterranean purple dye ‘factory’, PLOS ONE (2025). DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0321082