Among the many gods of Greek mythology, none embodies contradiction and paradox quite like Dionysus. He is the god of joy and terror, of liberation and destruction, of creativity and madness. To speak of Dionysus is to speak of transformation—the intoxication of wine, the rapture of dance, the ecstasy of music, and the frenzy that blurs the boundary between mortal and divine.

Dionysus is not a god who stays confined to the heights of Olympus. He descends to forests, mountains, and villages. He touches shepherds, kings, and commoners alike. He is as much at home in the rustic vineyards as in the grand halls of gods. His presence is intoxicating: at once sweet like grapes ripening in the sun and terrifying like a storm tearing through a hillside.

To understand Dionysus is to confront the deepest desires and fears within humanity—the longing for freedom, the danger of excess, and the strange beauty of surrender. He is a mirror of the human soul, reflecting both its light and its darkness.

The Birth of a Twice-Born God

Dionysus was no ordinary child. His story of birth alone reveals his extraordinary destiny. He was the son of Zeus, king of the gods, and Semele, a mortal princess of Thebes. But Hera, Zeus’s jealous wife, would not tolerate this union. Consumed by envy, she tricked Semele into demanding that Zeus reveal himself in his full divine glory. Bound by oath, Zeus complied. Yet the sight of his godly form was too much for a mortal to endure. Semele perished in flames, leaving her unborn child vulnerable.

In an act of desperation and love, Zeus saved the fetus by sewing him into his thigh until he was ready to be born. Thus Dionysus became the twice-born god—a being who crossed the threshold of death before even entering life. This unusual birth would mark his entire existence. He belonged neither fully to Olympus nor fully to Earth, but existed between boundaries: between life and death, order and chaos, joy and madness.

This dual nature made Dionysus a god of liminality—a figure who blurred categories and overturned conventions. He was at once divine and mortal, civilized and wild, male and effeminate, joyous and terrifying.

The Wandering God

Unlike many Olympians who reigned from fixed thrones, Dionysus was a wandering deity. His myths often portray him as a restless traveler, journeying across lands to spread the cultivation of the vine and the mysteries of his worship. From Asia Minor to Thrace, from India to Greece, Dionysus roamed the world, bringing with him the gifts of wine and the frenzy of ecstasy.

His wanderings were not merely geographical but symbolic. Dionysus was always a god of outsiders, a patron of those who lived on the margins of society—women, slaves, foreigners, and the oppressed. Wherever he went, he disrupted the established order. Kings who resisted him often faced ruin, while common people embraced his liberation with open arms.

To encounter Dionysus was to be challenged. He was not a god to be politely worshipped from a distance. He demanded immersion, participation, and surrender. Those who accepted his gifts found joy and freedom; those who resisted found madness and destruction.

The Symbols of Dionysus

Every god of Greece carried emblems that revealed their nature, and Dionysus was no exception. The most famous of his symbols is the vine—the twisting, climbing plant whose fruit transforms into wine. For the Greeks, the vine represented both cultivation and chaos. Wine required skill and labor to produce, yet its effects dissolved restraint and released primal emotions.

The thyrsus, a staff tipped with ivy or a pinecone, was another central symbol. It was not a weapon of violence but a symbol of fertility, abundance, and ecstatic energy. Wielded by Dionysus and his followers, it became an emblem of divine intoxication.

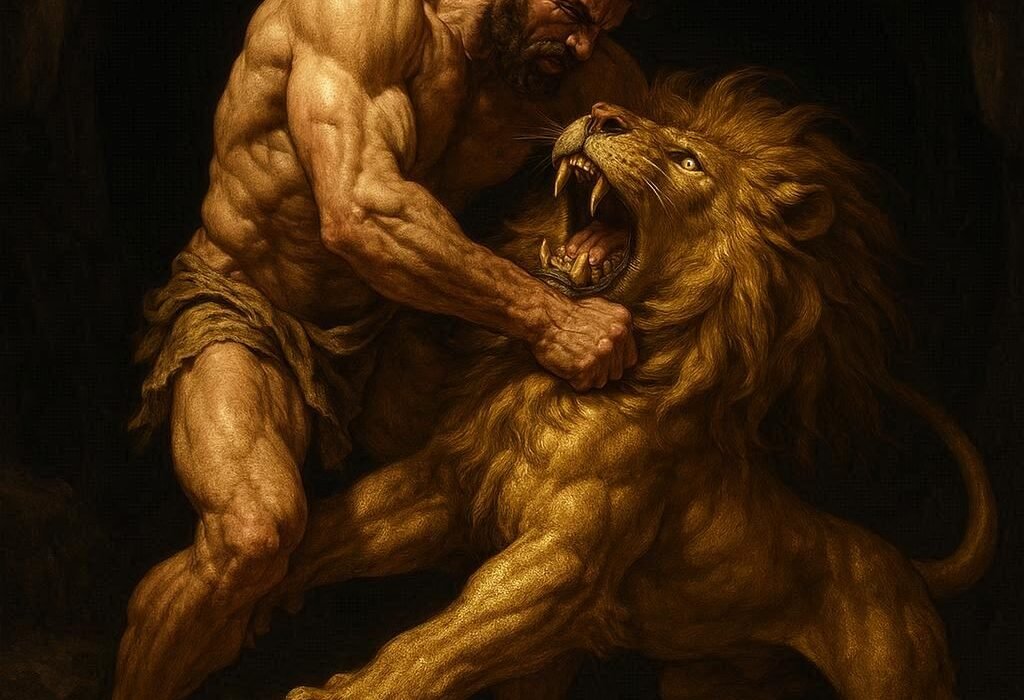

Animals, too, surrounded him: the leopard, the bull, and the serpent—all creatures associated with primal strength and untamed power. Dionysus himself could take animal form, shifting between shapes that unsettled the boundary between human and beast.

Perhaps most importantly, Dionysus was linked to the mask. In theater, his domain, masks represented transformation—the ability to step into another identity, to dissolve the boundaries of self. This reflected the essence of Dionysus: to lose oneself in ecstasy and become something greater.

The Maenads: Women in Ecstasy

No followers of Dionysus were more famous—or infamous—than the Maenads, women who abandoned their homes, families, and duties to join him in wild rituals. Clad in fawn skins, crowned with ivy, and wielding thyrsoi, they roamed mountains and forests, singing, dancing, and entering frenzied states of possession.

The Maenads embodied liberation from social order. In a patriarchal society that confined women to the domestic sphere, the worship of Dionysus gave them a rare outlet for freedom, expression, and power. Yet this liberation carried a darker side. The frenzied women were said to perform acts of extraordinary violence—tearing apart wild animals with their bare hands or even, in myth, dismembering men who resisted the god.

To the Greeks, the Maenads represented both fascination and fear. They revealed the intoxicating power of Dionysus to break chains, but also the danger of losing oneself entirely to frenzy.

The Dual Gifts of Wine

Wine, the most sacred gift of Dionysus, was itself a symbol of duality. It brought joy, laughter, and social bonding. It fueled poetry, music, and theater. In moderation, it was a gift of civilization, turning meals into feasts and gatherings into celebrations.

But wine also carried the seed of chaos. Too much could dissolve reason, awaken aggression, or plunge the drinker into despair. Dionysus, therefore, embodied both the blessing and the curse of intoxication. He was the god who lifted burdens from the soul, but also the god who led mortals into madness.

For the Greeks, this duality reflected the essence of life itself. To drink wine was to risk surrender, but also to taste freedom. To worship Dionysus was to embrace both sides of the coin—ecstasy and terror, joy and destruction.

Dionysus and Theater

Perhaps the most enduring legacy of Dionysus lies in the birth of theater. The great festivals of Dionysus in Athens, particularly the City Dionysia, gave rise to drama as we know it today.

Tragedies and comedies were performed in his honor, and the very act of stepping onto the stage was a ritual of transformation. Actors donned masks, becoming gods, heroes, or fools. The audience, united in collective emotion, experienced catharsis—an emotional purification that mirrored the ecstasy of Dionysian ritual.

In this way, Dionysus was not just the god of wine and madness, but also the god of art, creativity, and imagination. His domain stretched beyond vineyards into the heart of human expression. Theater, music, and poetry all carried his divine spark.

The Wrath of Dionysus

For all his gifts, Dionysus was not a god to be mocked or denied. Those who resisted his divinity often met tragic fates. The myths are full of warnings:

Pentheus, king of Thebes, refused to acknowledge Dionysus and tried to suppress his worship. For his arrogance, he was lured into spying on the Maenads, disguised as a woman. When they saw him, they tore him apart limb by limb in their frenzy.

Similarly, the daughters of King Minyas resisted the call of Dionysus, choosing to stay at their looms instead of joining his rites. In punishment, they were driven mad, slaughtered their own children, and were transformed into bats.

These tales served as cautionary myths. To deny Dionysus was to deny the forces of ecstasy, passion, and transformation within life itself. And those forces, when suppressed, erupted with devastating power.

Dionysus and Death

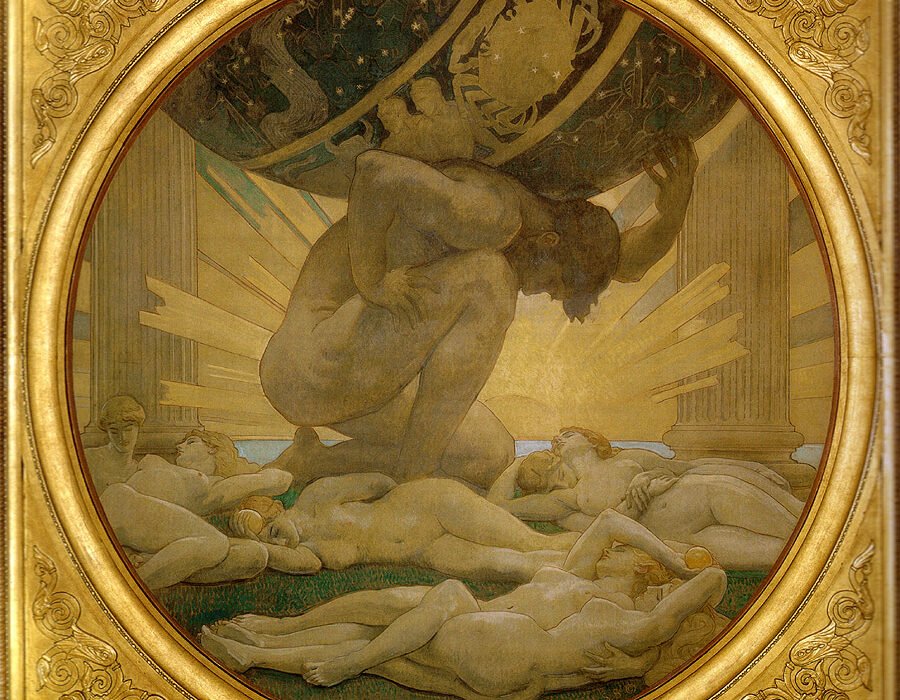

Unlike many other gods, Dionysus was deeply connected to death and rebirth. Some myths describe him as descending into the underworld to rescue his mother, Semele, bringing her back to Olympus as a goddess. Others speak of his dismemberment by the Titans, only to be reborn.

These stories align Dionysus with cycles of nature—the vine that withers in winter but blooms in spring, the grapes that are crushed but yield wine. He was a god of resurrection, of eternal return, of life arising from death.

This made him central to mystery religions, especially the Dionysian Mysteries, which promised initiates not just ecstasy in this life but hope for transformation beyond death.

The Universal Dionysus

Though rooted in Greek mythology, Dionysus transcended cultural boundaries. The Romans adopted him as Bacchus, and his cult spread across the Mediterranean. In India, he was associated with gods of fertility and ecstasy. In later philosophy and literature, from Nietzsche’s exploration of the “Dionysian” spirit to modern art and psychology, he became a symbol of primal energy, creativity, and chaos.

The universality of Dionysus lies in his embodiment of forces that exist in every human society: the tension between order and freedom, restraint and ecstasy, civilization and wilderness. He is not merely a Greek god but a timeless archetype, living wherever humans seek to transcend boundaries and taste something beyond themselves.

The Eternal Spirit of Dionysus

Dionysus is not easily confined to definitions. He is a god of contradictions, a deity of laughter and tears, of life and death, of structure and dissolution. His myths are not just ancient stories but reflections of the human condition.

In every glass of wine raised in celebration, in every song sung in rapture, in every theater performance that transforms reality, Dionysus still lives. He reminds us of the beauty of surrender, the danger of excess, and the mystery of life’s eternal cycle.

To honor Dionysus is to embrace the paradox of existence: that joy and madness are intertwined, that creation arises from chaos, and that to lose oneself is sometimes the only way to truly find oneself.