Since the earliest whispers of myth, humanity has looked beneath the ground and imagined another world. In the dark hollows of caves, in the depths of the earth where roots twist and rivers vanish, people believed there was a shadowy kingdom where the souls of the dead journeyed. In Greek mythology, this domain was Hades, named after its ruler—the stern god who governed all who passed from life into death.

The Greek Underworld was not merely a place of fear; it was also a place of order, reflection, and the natural cycle of existence. The Greeks imagined it as a vast, complex realm, not a simplistic hell of punishment but a place where every soul had its destiny. At the heart of this imagined world flowed its most striking features: five mythical rivers that wound like veins through the land of the dead.

These rivers were not merely boundaries of geography but boundaries of meaning. Each carried symbolic weight, embodying aspects of life, death, memory, and the divine. To cross them was to pass from the mortal to the eternal. To name them was to recognize the deepest human emotions—fear, grief, hatred, forgetfulness, and solemn vows.

To understand Hades and his rivers is to enter the heart of Greek myth itself, where death was not an end but a continuation, and where every soul traveled along the waters of fate.

Hades: The Lord of the Dead

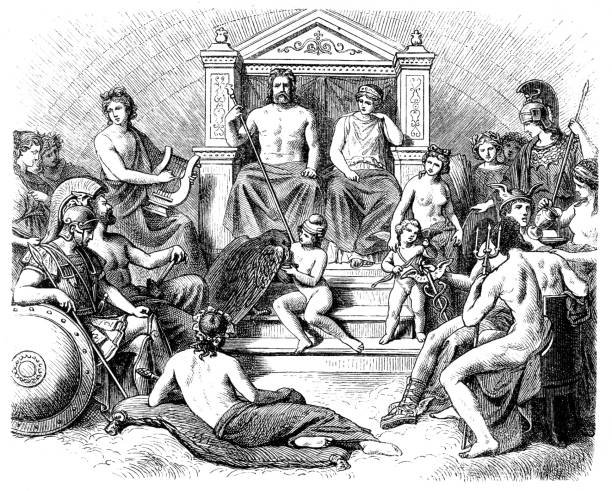

In Greek mythology, Hades was both the name of the Underworld and of the god who ruled it. The god Hades was the brother of Zeus and Poseidon, sons of the mighty Titan Cronus. When the three brothers overthrew their father and divided the cosmos, Zeus took the heavens, Poseidon took the sea, and Hades was given the realm beneath the earth.

Though often feared, Hades was not considered evil. He was not a devil in the Christian sense, but a solemn and impartial ruler. He was stern, unyielding, and just. His realm was a place of inevitability, where no soul could escape, and no bribe could sway judgment. Because of this, he was sometimes called Plouton, or “the wealthy one,” since all the treasures of the earth and all mortal souls eventually belonged to him.

Hades ruled alongside his queen, Persephone, who had been taken from the world above to become his bride. With her presence, the Underworld gained both dread and beauty, and the cycle of the seasons was forever bound to her yearly descent and return. Together, Hades and Persephone presided over the vast kingdom of the dead, a land both feared and revered.

But Hades’ realm was not uniform. It was divided into regions—the shadowy plains of Asphodel, the blissful Elysian Fields, the gloomy Tartarus, and the meadows of Lethe. And binding these regions together, shaping the paths of souls, flowed the great rivers of the Underworld.

The Rivers of the Underworld

The Greeks described five rivers flowing through the land of the dead. These rivers were not just waters but symbols, carrying the emotions and metaphysical forces that defined existence beyond life. They were the arteries of the Underworld, each with its own purpose and power.

Styx: The River of Hatred

Perhaps the most famous of the Underworld’s rivers was Styx, whose name means “hatred” or “abhorrence.” It was said to be the boundary between the living and the dead, the first river that every soul encountered after death. To cross Styx was to leave behind the world of the living and enter the shadowed kingdom of Hades.

The river Styx carried a sacred power unlike any other. Even the gods feared it. The Olympians swore their oaths upon its waters, for to break a vow made by the Styx was to invite ruin. A god who broke such a promise would be struck down, deprived of nectar and ambrosia for years, and cast into silence.

According to myth, Styx was also the mother of powerful children, such as Nike (Victory) and Kratos (Strength), who fought alongside Zeus in his war against the Titans. Her waters were so deadly that even a drop could kill a mortal. This deadly quality became central in myths such as that of Achilles, whose mother Thetis dipped him into the Styx to make him invulnerable—except for the heel she held him by, which remained his one weakness.

The Styx was not just a river but a sacred force that bound oaths, marked boundaries, and revealed the harsh absolutes of fate.

Acheron: The River of Woe

If Styx was the river of hatred, then Acheron was the river of sorrow. Its name means “river of woe” or “river of pain.” It was often described as a dark, sluggish river, carrying the grief of the dead who had not found peace.

The Acheron was the river most often associated with Charon, the ferryman of the dead. Souls of the newly departed would approach his boat, and only those who had been properly buried with a coin placed beneath their tongue could pay him to cross. Those who lacked payment wandered the shores of the Acheron, restless and forlorn, unable to reach the lands beyond.

The Acheron embodies the weight of mourning. It was believed to flow not only in the Underworld but also in certain places on earth, such as a river in Epirus in northwestern Greece, where people said the boundary between life and death grew thin. To stand near its waters was to feel the veil between worlds tremble.

Lethe: The River of Forgetfulness

Of all the rivers, Lethe is perhaps the most haunting. Its name means “oblivion” or “forgetfulness.” Souls who drank from its waters lost all memory of their earthly lives. In the Underworld, forgetfulness was not a cruelty but a necessity, for to carry the weight of mortal sorrows into eternity would be unbearable.

The River Lethe was also tied to the mysteries of rebirth. In some traditions, souls destined for reincarnation drank from Lethe so that they would not remember their past lives. To be reborn required forgetting the shadows of what had come before.

Yet Lethe carried both loss and mercy. To forget was to surrender identity, but it was also to find peace. Philosophers such as Plato imagined that the soul’s journey through Lethe was part of a cosmic cycle, where memory and forgetting balanced one another in the great wheel of existence.

Phlegethon: The River of Fire

Unlike the sluggish currents of Acheron or Lethe, the Phlegethon blazed with flames. Its name means “burning” or “fire-stream,” and it was described as a river of boiling fire that roared through the depths of the Underworld.

The Phlegethon embodied both torment and purification. In some accounts, it ran through Tartarus, the prison of the wicked, where it burned and seared the damned. In others, its flames were not destructive but cleansing, consuming impurities and leaving the soul bare.

Dante, in his Divine Comedy, centuries after the Greek myths, reimagined the Phlegethon as a river of boiling blood, fitting punishment for the violent. Yet in Greek thought, the Phlegethon’s fire was less about eternal punishment and more about the raw, elemental power of destruction and transformation.

It symbolized the flames of passion, wrath, and suffering—the fires that both destroy and renew.

Cocytus: The River of Lamentation

The final river was Cocytus, the river of wailing. Its name comes from the Greek kokytos, meaning “lamentation” or “crying.” It was said to be the river of tears, where the cries of the damned echoed forever.

The Cocytus was sometimes imagined as a frozen river, its still waters reflecting sorrow without release. Souls condemned to wander its banks were those who had been traitors, oath-breakers, or those guilty of great sins. Their eternal punishment was to dwell in despair, their cries mingling with the river’s mournful flow.

Yet Cocytus was not only about punishment. It symbolized the grief inherent in death itself—the cries of the living for the dead, and the sorrow of the dead for the life they had lost.

The Geography of the Dead

The five rivers were not separate streams but part of a vast and interconnected system. Ancient poets described them twisting and merging, circling the Underworld like veins around a heart.

Some traditions placed the Styx as a boundary at the edge of the Underworld, while Acheron flowed deeper inside. Lethe wound its way through the meadows of the dead, where souls wandered in oblivion. Phlegethon roared through Tartarus, while Cocytus formed the chilling boundary of sorrow.

Together, they created a landscape not only of geography but of emotion. The Underworld was not a flat, empty place but a realm structured by the rivers of memory, passion, grief, hatred, and forgetfulness. To journey through Hades was to journey through the deepest truths of the human condition.

The Symbolism of the Rivers

The Greeks, with their love of myth and metaphor, understood that these rivers were more than imaginary waters. They were reflections of universal forces:

- Styx represented the absolutes of loyalty and hatred.

- Acheron embodied sorrow and mourning.

- Lethe reflected the mercy and danger of forgetting.

- Phlegethon revealed the fiery nature of suffering and renewal.

- Cocytus gave voice to the cries of despair.

These rivers were the emotions and forces that flow through every human life. To imagine them as rivers in the realm of the dead was to externalize the inner landscape of the soul.

Hades and the Balance of Life

Through the image of Hades and his rivers, Greek mythology gave shape to humanity’s greatest mystery: what happens after death? The Greeks did not reduce the afterlife to punishment or reward alone. Instead, they created a world that reflected the complexity of existence itself.

Hades was stern but fair. His realm was dark but not without order. The rivers brought both pain and release, sorrow and peace. Death was not an enemy but a passage, and the Underworld was the place where all passages converged.

The Enduring Legacy of the Rivers

Even today, the names of these rivers echo in language and literature. To “cross the Styx” is still a metaphor for death. To “drink from Lethe” is to forget. Writers from Dante to modern novelists have drawn upon the imagery of Phlegethon’s fire or Cocytus’ wailing to describe human suffering.

These rivers endure because they touch something eternal in us. They are not just relics of Greek myth but living metaphors for the emotions we all encounter—anger, grief, passion, despair, and the longing to forget. They remind us that death, like life, is woven with meaning.

The Soul’s Journey

To imagine the journey of a soul through the Underworld is to imagine a passage across rivers of human experience. A soul arrives at the Styx, leaving behind the living. It crosses the Acheron, bearing the sorrow of loss. It wanders by Lethe, where memory fades. It encounters the fire of Phlegethon, where pain is burned away, and the wailing of Cocytus, where despair echoes.

And finally, it finds its place—whether in the meadows of Asphodel, the joys of Elysium, or the depths of Tartarus. Each river, each step, is part of the greater cycle.

In this way, the mythology of Hades and the rivers of the Underworld is not a tale of terror alone but a mirror of the human condition. It tells us that death is not merely an ending but a journey, a transformation, a passage through the waters that define what it means to live and to die.