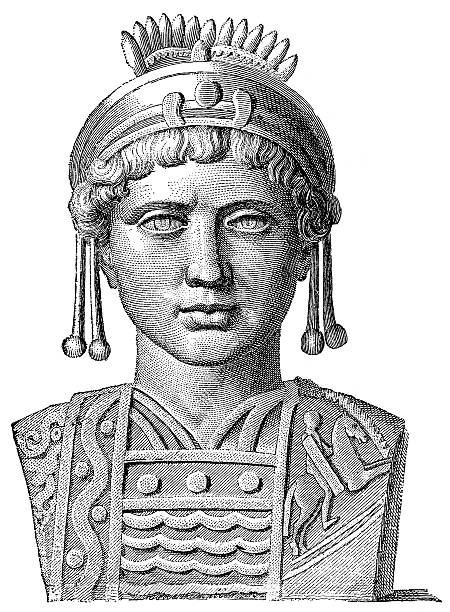

Justinian I (circa 482-565 CE) was Byzantine Emperor from 527 to 565, renowned for his ambitious efforts to restore the Roman Empire’s former glory and his significant contributions to Byzantine law and architecture. His reign is marked by the codification of Roman law, resulting in the Corpus Juris Civilis (Body of Civil Law), which profoundly influenced the development of legal systems in Europe. Justinian also undertook an extensive program of architectural renovation, including the construction of the Hagia Sophia, a masterpiece of Byzantine architecture. His military campaigns aimed to reconquer lost Western territories, achieving temporary success in North Africa and Italy. Despite facing internal challenges, such as the Nika riots, and external pressures from various barbarian groups, Justinian’s reign left a lasting impact on the Byzantine Empire, shaping its legal, cultural, and architectural heritage. His efforts helped to sustain the Byzantine Empire for centuries after his death.

Early Life and Background

Flavius Petrus Sabbatius Justinianus, commonly known as Justinian I, was born in 482 CE in the small village of Tauresium, located in what is today the Republic of North Macedonia. Although he rose to become one of the most powerful and influential emperors of the Byzantine Empire, his origins were quite humble. Justinian’s family was of Illyrian or Thracian descent, and they were not part of the Roman aristocracy. His father, Sabbatius, was a peasant, and his mother, Vigilantia, was the sister of Justin I, a man who would play a crucial role in Justinian’s rise to power.

Justinian’s early life was characterized by his rural upbringing, far from the political and cultural centers of the empire. Despite his modest beginnings, Justinian was a bright and ambitious young man. His uncle, Justin, had joined the Roman army and steadily climbed the ranks, eventually becoming a member of the imperial guard in Constantinople. Recognizing his nephew’s potential, Justin brought Justinian to the capital when he was still a young boy.

In Constantinople, Justinian received a formal education that was both comprehensive and rigorous. He studied a wide range of subjects, including theology, law, history, and philosophy, all of which would greatly influence his later reign. He also received military training, which was customary for young men of the time, particularly those with ambitions of leadership. Justinian’s intellectual and military education, combined with his natural abilities, prepared him well for the challenges that lay ahead.

Justinian’s relationship with his uncle was crucial to his future success. Justin was a shrewd and ambitious man who managed to position himself as one of the leading figures in the Byzantine court. When the Emperor Anastasius I died in 518 CE, Justin, despite his relatively low birth, was able to secure the throne, largely through his connections within the military and the support of key factions within the capital. As emperor, Justin I adopted Justinian, who was his sister’s son, and brought him into the inner circles of power.

This period marked the beginning of Justinian’s ascent within the Byzantine political hierarchy. Under Justin’s tutelage, he was given increasing responsibilities in the administration of the empire. His uncle’s elevation to the throne provided him with the opportunity to observe the workings of imperial power closely and to establish connections with important figures in the government and the church.

Despite his relatively young age, Justinian quickly gained a reputation for his intelligence, work ethic, and dedication to the empire. He was involved in various aspects of governance, from military campaigns to legal reforms, even before he officially became emperor. Justinian was also known for his piety, which endeared him to the religious establishment and the people alike. His deep Christian faith would later play a significant role in his policies as emperor.

During these years, Justinian also met and married Theodora, a woman of humble origins who would become one of the most powerful and influential empresses in Byzantine history. Theodora’s background was even more modest than Justinian’s; she was the daughter of a bear trainer and had worked as an actress, a profession that was often looked down upon in Byzantine society. However, Theodora was a woman of great intelligence, charm, and political acumen. Her marriage to Justinian was a partnership of equals, and she played a key role in his reign, offering advice and influencing decisions on a wide range of issues, from religious policy to social reforms.

The early life and background of Justinian I laid the foundation for his future achievements. His rise from a small village in the Balkans to the pinnacle of power in the Byzantine Empire is a testament to his abilities and the opportunities provided by his uncle’s position. However, it was Justinian’s own talents, his education, and his determination that ultimately allowed him to become one of the most significant figures in Byzantine history.

Rise to Power

Justinian’s rise to power was not merely a result of his uncle’s influence but also due to his own capabilities and strategic acumen. After Justin I ascended to the throne, Justinian quickly became his uncle’s most trusted advisor and confidant. Justin’s reign was characterized by a focus on securing the stability of the empire and preparing Justinian to succeed him. During this period, Justinian began to take on more significant roles within the government, including diplomatic missions, military campaigns, and administrative reforms.

One of the earliest demonstrations of Justinian’s influence was his involvement in the resolution of the Acacian Schism, a religious dispute that had divided the Eastern and Western branches of Christianity. The schism had arisen over theological differences and the appointment of certain bishops, leading to a rift between the Patriarch of Constantinople and the Pope in Rome. Justinian played a key role in negotiating a settlement that restored communion between the two churches in 519 CE. This achievement not only demonstrated his diplomatic skills but also reinforced his reputation as a devout Christian leader, a reputation that would be central to his reign.

As Justin aged and his health began to decline, Justinian’s influence in the empire grew even stronger. He was appointed co-emperor in April 527 CE, a clear indication that Justin intended for his nephew to succeed him. Just a few months later, on August 1, 527 CE, Justin died, and Justinian was proclaimed emperor. His rise to power was smooth and uncontested, a testament to the careful planning and preparation that had gone into securing his succession.

Justinian’s accession to the throne marked the beginning of a new era for the Byzantine Empire. He was determined to restore the glory of the Roman Empire and embarked on an ambitious program of military, legal, and architectural reforms. His reign would be characterized by his relentless pursuit of these goals, despite the significant challenges he faced.

One of Justinian’s first major challenges as emperor was the Nika Riots of 532 CE. The riots were sparked by political and social tensions within Constantinople, particularly among the factions of the Hippodrome, the Blues and the Greens. These factions were originally based on chariot racing teams but had evolved into powerful political groups with significant influence in the city. The riots began as a protest against the government’s harsh treatment of members of the factions but quickly escalated into a full-scale rebellion against Justinian’s rule.

For several days, Constantinople was in chaos as rioters set fire to buildings, including the Hagia Sophia, and demanded the overthrow of Justinian. The situation was dire, and many of Justinian’s advisors urged him to flee the city. However, it was Theodora who famously convinced him to stay and fight, declaring that she would rather die an empress than live in exile. Bolstered by her resolve, Justinian ordered his generals, Belisarius and Mundus, to suppress the revolt. The generals led a brutal crackdown in which thousands of rioters were killed, and the rebellion was crushed.

The Nika Riots were a pivotal moment in Justinian’s reign. The decisive action taken to end the riots not only saved his throne but also demonstrated his determination to maintain order and authority in the empire. The destruction of the Hagia Sophia also provided Justinian with the opportunity to embark on one of his most famous architectural projects: the rebuilding of the Hagia Sophia, which would become the crowning achievement of Byzantine architecture.

Following the Nika Riots, Justinian was more determined than ever to strengthen his rule and achieve his vision for the empire. He embarked on a series of military campaigns aimed at reclaiming former Roman territories in the West, which had been lost to various barbarian kingdoms following the fall of the Western Roman Empire. His military efforts were led by his two most capable generals, Belisarius and Narses, who would achieve significant victories in North Africa, Italy, and Spain.

At the same time, Justinian also focused on internal reforms, particularly in the legal and administrative spheres. He was determined to create a unified and coherent legal system for the empire, which led to the creation of the Corpus Juris Civilis, or the Code of Justinian. This monumental legal code would have a lasting impact on the development of law in Europe and beyond.

Justinian’s rise to power was marked by his ability to navigate the complex political landscape of the Byzantine Empire, his strategic use of military force, and his commitment to his vision of a revitalized Roman Empire. Despite the challenges he faced, including the Nika Riots, Justinian emerged as a strong and determined leader who would leave an indelible mark on the history of the Byzantine Empire.

Reforms and Legal Legacy

One of Justinian I’s most enduring legacies is his comprehensive legal reform, encapsulated in the Corpus Juris Civilis, or the Code of Justinian. This monumental project aimed to streamline and codify centuries of Roman law into a coherent and accessible system, reflecting Justinian’s vision of a unified and orderly empire.

When Justinian ascended the throne, Roman law was a complex and fragmented collection of statutes, decrees, legal opinions, and traditions accumulated over nearly a thousand years. The sheer volume of laws and the inconsistencies among them created confusion and inefficiency, both in the courts and in the administration of the empire. Justinian recognized that legal reform was essential not only for the effective governance of the state but also for the realization of his broader goal of restoring the grandeur of the Roman Empire.

In 528 CE, Justinian appointed a commission of legal experts, headed by the eminent jurist Tribonian, to undertake the monumental task of revising and codifying Roman law. The work was divided into three main parts: the Codex Justinianus, the Digesta or Pandects, and the Institutiones. Together, these formed the Corpus Juris Civilis, which would become the foundation of legal systems in many European countries and influence legal thought for centuries.

The Codex Justinianus was the first part of the project and was completed in 529 CE. It was a compilation of imperial constitutions and decrees issued by Roman emperors from the time of Hadrian (117-138 CE) up to Justinian himself. The Codex sought to eliminate outdated or contradictory laws and to organize the remaining statutes into a coherent and logical system. This collection was intended to serve as the primary legal reference for judges and administrators throughout the empire.

The second part of the Corpus Juris Civilis, the Digesta or Pandects, was completed in 533 CE. This massive work consisted of extracts from the writings of Roman jurists, compiled into fifty books. The Pandects were intended to provide a comprehensive summary of legal principles and precedents, covering every aspect of Roman law, from contracts and property to criminal law and procedure. The compilation process involved selecting and organizing legal opinions from over 2,000 books written by prominent Roman jurists, a task of immense complexity and importance.

The Institutiones, also completed in 533 CE, served as a legal textbook for students and those new to Roman law. It was designed to introduce the basic principles of law in a clear and systematic manner, making it easier for future generations of lawyers, judges, and officials to understand and apply the law. The Institutiones were divided into four books, covering topics such as the legal status of persons, property law, obligations, and actions.

In 534 CE, the Codex Justinianus was revised and updated to incorporate the new laws and legal principles that had been established during the codification process. This revised version, known as the Codex Repetitae Praelectionis, was intended to be the definitive legal code of the Byzantine Empire, ensuring that all citizens and officials were governed by the same set of laws.

The Corpus Juris Civilis was more than just a legal code; it was a reflection of Justinian’s vision for his empire. He saw the law as a tool for promoting justice, order, and unity, and he believed that a well-organized legal system was essential for the stability and prosperity of the state. The legal reforms he enacted were intended not only to address the immediate needs of the empire but also to ensure its long-term survival and success.

Justinian’s legal reforms had a profound and lasting impact on the development of law, both within the Byzantine Empire and beyond. The Corpus Juris Civilis became the foundation of the legal systems in many European countries during the Middle Ages and the Renaissance. It influenced the development of canon law, which governed the Christian church, and it served as a model for the legal codes of many modern nations.

In addition to his work on the Corpus Juris Civilis, Justinian also undertook reforms in other areas of governance. He sought to improve the administration of justice by appointing competent and honest judges and by taking measures to combat corruption and abuse of power. He also implemented financial reforms aimed at stabilizing the empire’s economy, including measures to improve tax collection and to regulate the currency.

However, Justinian’s reforms were not without their critics. Some viewed his legal codification as overly rigid and inflexible, arguing that it stifled legal innovation and adaptation. Others criticized the emperor’s heavy-handed approach to governance, particularly his use of legal and administrative reforms to centralize power in the hands of the emperor and to suppress dissent.

Despite these criticisms, Justinian’s legal legacy is undeniable. The Corpus Juris Civilis remains one of the most important legal texts in history, and its influence can be seen in the legal systems of many countries around the world today. Justinian’s vision of a unified and orderly empire, governed by a coherent and just legal system, continues to resonate with legal scholars and practitioners centuries after his death.

Military Campaigns and Expansion

Justinian I’s reign is often characterized by his ambitious and extensive military campaigns, which were aimed at restoring the territorial integrity of the Roman Empire. His vision of Renovatio Imperii—the restoration of the Roman Empire—drove him to embark on a series of wars that sought to reclaim lost territories in the West and secure the empire’s borders against external threats. Under the leadership of his brilliant generals, particularly Belisarius and Narses, Justinian managed to achieve significant, though temporary, military successes that extended Byzantine influence across the Mediterranean.

One of the earliest and most successful of Justinian’s military campaigns was the Vandalic War in North Africa. The Vandals, a Germanic tribe, had established a kingdom in the former Roman provinces of North Africa, including the wealthy city of Carthage. The Vandals were notorious for their piracy in the Mediterranean and their persecution of Catholics, who looked to Constantinople for support. In 533 CE, Justinian sent a formidable expeditionary force under the command of General Belisarius to North Africa. The campaign was a resounding success. Belisarius quickly defeated the Vandal king, Gelimer, at the Battle of Ad Decimum near Carthage, and by March 534 CE, the Vandal kingdom was dismantled, and North Africa was reintegrated into the Byzantine Empire as the Praetorian Prefecture of Africa.

This victory not only restored North Africa to imperial control but also secured the grain supply to Constantinople, a crucial factor for the city’s sustenance. It also bolstered Justinian’s reputation as a restorer of Roman lands, setting the stage for further conquests.

Following the success in North Africa, Justinian turned his attention to Italy, where the Ostrogoths had established a kingdom following the fall of the Western Roman Empire. The Gothic War (535-554 CE) was one of Justinian’s most prolonged and challenging campaigns. Once again, Belisarius was at the forefront of the conflict, leading a series of campaigns that saw the Byzantines capture key cities, including Rome, Naples, and Ravenna, the Ostrogothic capital. Despite these successes, the war dragged on due to the resilience of the Ostrogoths and the difficulty of maintaining control over a war-torn Italy.

The Gothic War was marked by numerous setbacks, including a severe outbreak of the plague in 541 CE, which devastated the population of the empire, including its military forces. The war also placed a tremendous strain on the Byzantine treasury, as the costs of sustaining military operations in Italy mounted. However, by 554 CE, the Byzantine forces, now under the command of the general Narses, had finally subdued the Ostrogoths, and Italy was once again under Roman control. This victory was formalized with the Pragmatic Sanction of 554, which reorganized Italy as part of the Byzantine Empire.

The reconquest of Italy was seen as the crowning achievement of Justinian’s military efforts, as it symbolized the restoration of Roman rule over the Western heartland. However, the prolonged conflict left much of Italy in ruins, and the Byzantine hold on the peninsula was fragile and short-lived, eventually succumbing to the Lombard invasions in the later 6th century.

Simultaneously, Justinian’s forces were also active in the Iberian Peninsula, where the Visigoths had established a kingdom. In 552 CE, Justinian sent a force under the command of the general Liberius to conquer parts of southern Spain. The Byzantines succeeded in capturing several coastal cities, including Cartagena and Córdoba, and established the province of Spania. While this foothold was small compared to Justinian’s conquests in Africa and Italy, it represented the westernmost extent of Byzantine power and a symbolic link to the Roman past.

In addition to these Western campaigns, Justinian also had to contend with threats to the eastern borders of the empire, particularly from the Sassanian Empire. The Byzantine-Sassanian War of 540-562 CE was a protracted conflict that saw both sides suffer heavy losses. The Sassanians, led by King Khosrow I, invaded and sacked the city of Antioch in 540 CE, dealing a severe blow to Byzantine prestige. However, Justinian managed to stabilize the situation through a combination of military resistance and diplomacy, eventually concluding a truce with the Sassanians in 562 CE, which secured the eastern borders of the empire for a time.

Throughout these campaigns, Justinian demonstrated a remarkable commitment to his vision of restoring the Roman Empire. However, his military endeavors came at a great cost. The empire’s finances were severely strained by the constant warfare, and the heavy taxation needed to fund the military campaigns led to unrest and dissatisfaction among the population. The heavy financial burden placed on the empire by Justinian’s wars exacerbated social tensions and contributed to various revolts and uprisings during his reign. The high taxes were particularly resented in the newly reconquered territories, where the population had already suffered from years of warfare and instability.

In Italy, for example, the prolonged Gothic War devastated the economy, leaving much of the countryside depopulated and the cities in ruins. The Byzantine administration, seeking to recoup the costs of the war, imposed heavy taxes on the Italian population. This created resentment among the local aristocracy and common people alike, leading to a lack of popular support for the Byzantine rulers and making the region more vulnerable to later invasions by the Lombards.

Similarly, in North Africa, the initial enthusiasm for liberation from Vandal rule quickly faded as the local population faced the realities of Byzantine governance. The heavy tax demands, coupled with the corrupt practices of some Byzantine officials, led to widespread dissatisfaction. This unrest made it difficult for the Byzantines to maintain control over the region and contributed to a series of rebellions, including the Moorish uprisings, which further destabilized the province.

In addition to the financial strain, Justinian’s military campaigns also stretched the empire’s resources and military manpower to their limits. The constant need to defend and secure the newly reconquered territories meant that the Byzantine army was often overextended, leading to difficulties in responding to new threats. The plague that struck the empire in 541 CE, known as the Plague of Justinian, further depleted the population and weakened the empire’s ability to sustain prolonged military campaigns.

Despite these challenges, Justinian’s military campaigns did achieve significant territorial gains and temporarily restored the Roman Empire’s influence over much of the Mediterranean. However, the cost of these victories was immense, both in terms of human lives and economic resources. The financial and social strains caused by the wars would have long-lasting effects on the Byzantine Empire, contributing to its vulnerability in the years following Justinian’s death.

Ultimately, while Justinian’s military ambitions succeeded in expanding the empire’s borders, they also left the state in a precarious position. The heavy toll of constant warfare, combined with the strain on the empire’s finances and the dissatisfaction of the populace, would contribute to the decline of Byzantine power in the centuries to come. Justinian’s dream of a restored Roman Empire was, in many ways, fleeting, as the territories he reconquered would eventually be lost, and the challenges he left behind would continue to haunt his successors.

Religious Policy and Ecclesiastical Affairs

Religion played a central role in Justinian I’s reign, and his policies in this area were driven by his deep Christian faith and his desire to unify the empire under a single, orthodox belief system. Justinian viewed himself as a defender of the faith, and his reign was marked by efforts to strengthen the position of the Orthodox Church, combat heresy, and assert the emperor’s authority over ecclesiastical matters.

One of the most significant aspects of Justinian’s religious policy was his commitment to enforcing Orthodox Christianity as the state religion of the Byzantine Empire. This commitment was reflected in his vigorous persecution of various religious groups deemed heretical or pagan. Among the heresies Justinian targeted was Monophysitism, a theological doctrine that held that Christ had a single divine nature rather than two natures, one divine and one human. Monophysitism had a strong following in regions such as Egypt and Syria, and Justinian saw it as a threat to the unity of the empire.

Throughout his reign, Justinian sought to suppress Monophysitism and other heresies through a combination of legal measures and ecclesiastical actions. He issued edicts condemning heretical beliefs, ordered the closure of heretical places of worship, and exiled or imprisoned prominent heretical leaders. At the same time, he attempted to reconcile with the Monophysite communities by promoting theological dialogue and seeking compromises, although these efforts were often met with resistance from both sides.

In 553 CE, Justinian convened the Second Council of Constantinople, which is considered the Fifth Ecumenical Council by the Orthodox Church. The council was intended to resolve the ongoing theological disputes and reaffirm the decisions of the previous councils, particularly the Council of Chalcedon, which had defined the doctrine of Christ’s two natures. The council condemned certain writings and theologians associated with Nestorianism, another heresy that emphasized the distinction between Christ’s divine and human natures, and it sought to address the concerns of the Monophysites. However, the council’s decisions did not fully satisfy either side, and the religious divisions within the empire persisted.

Justinian’s religious policies were not limited to combating heresy; he also took measures to strengthen the Orthodox Church and its institutions. He was a prolific builder of churches, with the most famous being the reconstruction of the Hagia Sophia in Constantinople. This magnificent cathedral, completed in 537 CE, was a symbol of the emperor’s devotion to Christianity and his desire to glorify God through architecture. The Hagia Sophia became the centerpiece of Orthodox worship in the empire and remains one of the most iconic structures in the world.

In addition to his architectural contributions, Justinian sought to increase the authority of the patriarchate of Constantinople and to bring the church under closer imperial control. He enacted laws that regulated the appointment of bishops, the administration of church property, and the conduct of clergy. Justinian believed that the emperor had a God-given duty to oversee the church and to ensure that it remained true to Orthodox teachings. This belief in imperial authority over the church, known as Caesaropapism, was a defining feature of his religious policy and would influence the relationship between church and state in the Byzantine Empire for centuries.

Justinian’s religious zeal also extended to his dealings with other Christian communities outside the Byzantine Empire. He sought to establish his authority as a protector of Christians beyond the empire’s borders, particularly in the Eastern Christian communities under Sassanian rule. Through diplomatic efforts and financial support, Justinian aimed to strengthen the position of Christians in Persia and other regions, asserting his role as the defender of the faith.

Despite his efforts to promote religious unity, Justinian’s policies often led to tension and conflict. His persecution of heretical groups and pagans created resentment and resistance, particularly in regions with strong non-Orthodox traditions. In some cases, these policies exacerbated existing divisions and contributed to unrest, as seen in the Monophysite strongholds of Egypt and Syria. Moreover, Justinian’s attempts to assert imperial control over the church sometimes put him at odds with the clergy, particularly when his policies were seen as infringing on the independence of the church.

The impact of Justinian’s religious policies was profound and long-lasting. His efforts to enforce Orthodox Christianity helped to shape the religious landscape of the Byzantine Empire and to define the role of the emperor as a religious as well as a political leader. However, his policies also highlighted the challenges of achieving religious unity in a diverse and multi-ethnic empire. The religious divisions that persisted after Justinian’s reign would continue to be a source of tension and conflict in the Byzantine Empire for centuries.

Cultural and Architectural Contributions

Justinian I’s reign was marked by significant cultural and architectural achievements that left a lasting legacy on the Byzantine Empire and the wider world. His patronage of the arts, literature, and architecture was driven by his desire to glorify the empire and to establish a lasting testament to his rule. Among his many contributions, the construction of the Hagia Sophia stands out as the crowning achievement of his architectural endeavors.

The Hagia Sophia, which means “Holy Wisdom,” was originally built by Emperor Constantine I in the 4th century and later expanded by Emperor Theodosius II. However, the original structure was destroyed during the Nika Riots of 532 CE. In the aftermath of the riots, Justinian decided to rebuild the cathedral on a grander scale, reflecting the glory of the empire and the Christian faith. The new Hagia Sophia, designed by the architects Isidore of Miletus and Anthemius of Tralles, was completed in 537 CE and became the largest cathedral in the world for nearly a thousand years.

The Hagia Sophia is renowned for its massive dome, which at the time was considered an engineering marvel. The dome appears to float above the central space, supported by a series of pendentives and hidden buttresses that distribute its weight. The interior of the cathedral was richly decorated with mosaics, marble, and precious stones, creating a sense of awe and reverence for those who entered. The Hagia Sophia not only served as the principal church of the Byzantine Empire but also as a symbol of the empire’s spiritual and temporal power. It would later influence the design of many other churches and mosques, particularly in the Islamic world, after Constantinople fell to the Ottomans in 1453.

In addition to the Hagia Sophia, Justinian undertook the construction of numerous other churches, monasteries, and public buildings throughout the empire. Among these were the Church of San Vitale in Ravenna, the Church of Saints Sergius and Bacchus in Constantinople, and the Basilica of Saint Catherine at Mount Sinai. These buildings were not only places of worship but also served as expressions of the emperor’s piety and his commitment to the Christian faith. Justinian’s architectural projects extended beyond religious buildings to include the construction of fortifications, aqueducts, bridges, and roads, all of which contributed to the infrastructure and defense of the empire.

Justinian’s patronage also extended to the arts and literature. During his reign, there was a revival of classical learning and a flourishing of Byzantine culture. The emperor supported the work of historians, theologians and scholars, whose writings helped to preserve and transmit the knowledge of the ancient world to future generations. Among the most notable figures of this period was Procopius, the official court historian, who documented Justinian’s reign in a series of works that provide invaluable insights into the era.

Procopius’ major works include the Wars of Justinian, which chronicles the military campaigns of Justinian’s generals, particularly Belisarius, and the Buildings of Justinian, which celebrates the emperor’s extensive architectural projects throughout the empire. However, Procopius is perhaps best known for his Secret History, a scathing and critical account of Justinian, Empress Theodora, and the court. This work, written in secret, reveals the darker aspects of Justinian’s reign, including allegations of tyranny, corruption, and moral depravity. Together, these works provide a complex and multifaceted picture of Justinian’s rule, reflecting both his achievements and the controversies that surrounded him.

Justinian’s reign also saw a significant contribution to theological literature. The emperor was deeply involved in religious debates and sought to influence the development of Christian doctrine. He commissioned theological treatises and supported the work of prominent theologians who defended Orthodox Christianity against heresies. Justinian himself authored several works on theology, including letters and edicts addressing various doctrinal issues. His commitment to theological scholarship was part of his broader effort to strengthen the Orthodox Church and to establish a unified Christian doctrine that would support the spiritual and political unity of the empire.

The arts flourished under Justinian’s patronage, particularly in the form of mosaic art, which became one of the most distinctive features of Byzantine culture. Mosaics were used to decorate churches, palaces, and public buildings, depicting religious scenes, imperial portraits, and symbolic imagery. The mosaics of the Hagia Sophia, for example, were renowned for their intricate designs and vibrant colors, which conveyed both the spiritual grandeur of the Christian faith and the political power of the emperor.

In addition to mosaics, Justinian’s reign saw the continuation and refinement of iconography, the practice of creating religious images or icons that played a central role in Orthodox Christian worship. These icons were believed to serve as windows to the divine, and they were venerated in both public and private devotions. The production of icons became a highly developed art form during Justinian’s reign, with artists adhering to strict conventions that ensured the theological accuracy and spiritual efficacy of their work.

Justinian’s architectural and cultural achievements were not limited to Constantinople; they extended throughout the empire, from the newly reconquered territories in the West to the distant provinces in the East. This widespread patronage helped to disseminate Byzantine culture and to establish a common artistic and architectural language that would endure for centuries. The influence of Justinian’s cultural policies can be seen in the development of Byzantine art and architecture in subsequent centuries, as well as in the cultural traditions of the Eastern Orthodox Church.

However, Justinian’s cultural legacy was also marked by challenges and contradictions. While his patronage of the arts and learning contributed to a flourishing of Byzantine culture, his religious policies, particularly his persecution of heretics and pagans, led to the destruction of many works of classical literature and art that were deemed incompatible with Christian orthodoxy. This tension between cultural revival and religious orthodoxy was a defining feature of Justinian’s reign, reflecting the complex relationship between tradition and innovation in the Byzantine Empire.

In summary, Justinian’s contributions to culture and architecture were among the most enduring aspects of his legacy. His ambitious building projects, particularly the Hagia Sophia, transformed the architectural landscape of the empire and set new standards for ecclesiastical and public architecture. His support for the arts and literature helped to preserve the knowledge of the ancient world and to foster a vibrant Byzantine culture that would influence the development of Christian art and thought for centuries. Despite the challenges and controversies that accompanied his reign, Justinian’s cultural and architectural achievements remain a testament to his vision of a restored and unified Roman Empire.

The Plague of Justinian and Its Impact

One of the most devastating events during Justinian I’s reign was the outbreak of the Plague of Justinian, a pandemic that struck the Byzantine Empire and much of the known world in the mid-6th century. The plague, which first appeared in Constantinople in 541 CE, is considered one of the deadliest pandemics in history, causing widespread mortality and profoundly affecting the social, economic, and political fabric of the empire.

The Plague of Justinian is believed to have been caused by the bacterium Yersinia pestis, the same pathogen responsible for the later Black Death in the 14th century. The disease spread rapidly through the empire, likely carried by fleas that infested black rats, which were common on ships and in urban areas. The origins of the plague are thought to have been in the regions around the Nile River, and it spread along trade routes, reaching Constantinople and other major cities with alarming speed.

The outbreak in Constantinople was particularly severe, with contemporary accounts describing the city as overwhelmed by the sheer number of dead. The historian Procopius, who witnessed the plague firsthand, provided a vivid and harrowing description of its impact. According to Procopius, thousands of people died each day, and the city’s infrastructure was unable to cope with the mass burials required. Bodies were piled up in the streets, and the stench of decay filled the air. The scale of the death toll was such that many homes were left vacant, and the economy ground to a halt as people fled or succumbed to the disease.

The impact of the plague on the Byzantine Empire was catastrophic. It is estimated that the plague killed between 25% and 50% of the population of Constantinople, with similarly high mortality rates reported in other parts of the empire. The loss of such a large portion of the population had immediate and long-term consequences for the empire. The labor force was decimated, leading to shortages in agricultural production, a decline in trade, and a rise in food prices. The resulting economic downturn exacerbated the financial strains already imposed by Justinian’s military campaigns and building projects.

In addition to its economic impact, the plague also weakened the Byzantine military, which was already stretched thin by Justinian’s wars of reconquest. The loss of soldiers to the disease, coupled with the difficulty of recruiting new troops from a reduced population, left the empire vulnerable to external threats. The Goths in Italy and the Persians on the eastern front both took advantage of the empire’s weakened state, leading to renewed conflicts that further drained the empire’s resources.

The plague also had a profound psychological impact on the population. The sheer scale of the death and the apparent randomness with which it struck led many to believe that the plague was a sign of divine wrath. Religious responses to the plague varied, with some viewing it as a call to repentance and others seeing it as a test of faith. The church played a central role in providing spiritual comfort to the afflicted, and many turned to prayer and religious rituals in an attempt to ward off the disease.

The Plague of Justinian continued to recur in waves for several years, with outbreaks reported as late as the 570s CE. These repeated outbreaks further eroded the stability of the empire and hindered its recovery from the initial shock of the pandemic. The cumulative effect of the plague was a significant weakening of the Byzantine Empire, making it more difficult for Justinian and his successors to maintain control over the territories he had reconquered and to defend the empire’s borders from external threats.

In the long term, the Plague of Justinian had far-reaching consequences for the history of the Mediterranean world. The dramatic population decline contributed to the weakening of the Byzantine Empire and the eventual loss of its western territories. The economic disruption caused by the plague also had a lasting impact on trade and commerce, contributing to the decline of urban centers and the shift towards a more rural, agrarian economy in many parts of the empire.

Moreover, the social and political instability caused by the plague created opportunities for the rise of new powers in the region. In the West, the Lombards took advantage of the weakened Byzantine control in Italy to establish their own kingdom, while in the East, the Sassanian Empire continued to challenge Byzantine authority. The long-term demographic and economic effects of the plague also set the stage for the rise of Islam in the 7th century, as the weakened Byzantine and Sassanian empires were unable to effectively resist the rapid expansion of the Arab Caliphates.

In conclusion, the Plague of Justinian was a catastrophic event that had a profound impact on the Byzantine Empire and the broader Mediterranean world. The pandemic not only caused immense loss of life but also contributed to the economic, military, and political decline of the empire. The challenges posed by the plague tested Justinian’s leadership and ultimately revealed the limits of his ambitious vision for the restoration of the Roman Empire. The legacy of the Plague of Justinian serves as a reminder of the vulnerability of even the most powerful empires to the forces of nature and the fragility of human societies in the face of pandemics.

Justinian’s Legacy and Evaluation

Justinian I, often referred to as “Justinian the Great,” is remembered as one of the most significant and complex figures in Byzantine history. His reign, marked by ambitious projects, military campaigns, religious controversies, and monumental achievements, has been the subject of both admiration and criticism by historians and scholars. Evaluating Justinian’s legacy involves weighing his accomplishments against the challenges and controversies that defined his time on the throne.

One of the most enduring aspects of Justinian’s legacy is his legal reform, embodied in the Corpus Juris Civilis. This monumental codification of Roman law has had a profound and lasting impact on the development of legal systems around the world. The Corpus Juris Civilis served as the foundation of Byzantine law and influenced legal traditions in Western Europe, the Middle East, and beyond. It became the basis for many modern legal systems, particularly in continental Europe, where it was rediscovered and studied during the Middle Ages and the Renaissance. The principles enshrined in Justinian’s code, including the concepts of justice, equity, and the rule of law, have shaped the development of civil law traditions and continue to resonate in legal thinking to this day.

The Corpus Juris Civilis is divided into four main parts: the Codex Justinianus (a collection of imperial constitutions), the Digest or Pandects (a compilation of legal writings and opinions from Rome’s greatest jurists), the Institutes (a textbook for law students), and the Novellae (new laws enacted during Justinian’s reign). This comprehensive legal code was intended to clarify and consolidate the complex and often contradictory body of Roman law that had accumulated over centuries. By organizing and systematizing the law, Justinian sought to create a legal framework that would bring order and stability to the Byzantine Empire.

Justinian’s legal reforms extended beyond the codification of laws; they also reflected his vision of a just and orderly society. The emperor believed that the law was a divine instrument for governing the empire and that it was his duty to ensure that it was administered fairly and effectively. This belief in the importance of law as a tool for maintaining social order and justice is one of the reasons why Justinian’s legal legacy has endured.

However, while the Corpus Juris Civilis was a remarkable achievement, it was not without its challenges. The implementation of the code across the diverse and far-flung territories of the Byzantine Empire was a complex and often contentious process. Local customs and legal traditions sometimes clashed with the new imperial laws, leading to resistance and difficulties in enforcement. Moreover, the heavy taxation and strict legal measures introduced under Justinian’s reforms contributed to social unrest in some regions, exacerbating tensions between the central government and provincial populations.

Beyond his legal reforms, Justinian’s legacy is also shaped by his ambitious military campaigns aimed at reconquering the western territories of the former Roman Empire. While these campaigns achieved significant territorial gains, including the temporary restoration of imperial control over Italy, North Africa, and parts of Spain, they also placed a tremendous strain on the empire’s resources. The cost of maintaining these conquests, combined with the financial burdens of Justinian’s extensive building projects, such as the Hagia Sophia, led to economic difficulties and discontent among the populace.

Justinian’s religious policies further complicate his legacy. His efforts to enforce Orthodox Christianity and suppress heretical beliefs, while intended to unify the empire under a single faith, often led to religious tensions and conflicts. The emperor’s harsh treatment of heretical groups, particularly the Monophysites, created deep-seated resentment in regions like Egypt and Syria, which contributed to the later weakening of Byzantine control in these areas. Justinian’s religious zeal, while admirable in its intent, sometimes undermined the stability and cohesion of the empire.

The Plague of Justinian, which struck the empire in 541 CE, also had a profound impact on Justinian’s reign and his legacy. The pandemic decimated the population, weakened the economy, and left the empire vulnerable to external threats. Although Justinian’s leadership during this crisis was characterized by resilience and determination, the long-term effects of the plague contributed to the decline of the Byzantine Empire in the years following his death.

In evaluating Justinian’s legacy, it is important to recognize both his remarkable achievements and the challenges that he faced. On one hand, Justinian was a visionary leader whose legal, cultural, and architectural contributions had a lasting impact on the Byzantine Empire and the broader world. His efforts to restore the Roman Empire’s glory, through military conquests and the codification of Roman law, were ambitious and far-reaching. On the other hand, his reign was also marked by significant difficulties, including economic strain, social unrest, religious conflicts, and the devastating effects of the plague.

Ultimately, Justinian’s legacy is a complex and multifaceted one. He is remembered as a great lawgiver, a patron of the arts and architecture, and a determined ruler who sought to revive the Roman Empire. At the same time, his reign serves as a cautionary tale about the limits of imperial ambition and the challenges of maintaining a vast and diverse empire in the face of external and internal pressures. Justinian’s contributions to law, culture, and statecraft continue to be studied and admired, but his legacy also invites reflection on the challenges of leadership and the consequences of pursuing grandiose visions in a world fraught with uncertainties.