Mahavira (c. 599–527 BCE) was a significant figure in ancient Indian philosophy and the 24th Tirthankara in Jainism. Renowned for his teachings on non-violence, non-possessiveness, and self-discipline, Mahavira is considered a reformer and key proponent of Jain principles. His life was marked by a rigorous asceticism and a quest for spiritual liberation, which he achieved through years of meditation and self-denial. Mahavira’s doctrines emphasized the importance of karma and the path to achieving moksha (liberation) through ethical living, truthfulness, and non-attachment. His teachings have profoundly influenced Jain philosophy and ethics, stressing the significance of non-violence (ahimsa) and respect for all living beings. Mahavira’s contributions helped establish Jainism as a major philosophical and religious tradition in India, and his principles continue to be central to Jain practice and belief.

Early Life and Background

Mahavira, originally named Vardhamana, was born around 599 BCE in Kundagrama, a village near Vaishali in present-day Bihar, India. His birth was an auspicious event for his family, as he was born into the noble Kshatriya caste, part of the royal Ikshvaku dynasty. His father, Siddhartha, was the chief of the Naya tribe, and his mother, Trishala, was from the powerful Lichchhavi clan. Both his parents were followers of Parshvanatha, the 23rd Tirthankara of Jainism, which influenced Mahavira’s early religious inclinations.

Vardhamana grew up in the lap of luxury, surrounded by the comforts of palace life. From an early age, he exhibited remarkable physical strength, courage, and a profound sense of detachment. His childhood was marked by acts of valor and bravery, which earned him the name “Mahavira” or “Great Hero.” This name symbolized his exceptional qualities of mind and spirit that were to define his later life.

Despite the luxuries of royal life, Mahavira exhibited a deep inclination toward spiritual pursuits. The influence of his parents’ religious beliefs, particularly the teachings of Parshvanatha, played a significant role in shaping his worldview. From a young age, Mahavira showed an interest in understanding the nature of the self, suffering, and the world beyond material existence.

At the age of 28, after the death of his parents, Mahavira decided to renounce worldly life in pursuit of spiritual enlightenment. This decision was not sudden but the result of years of contemplation. He believed that the material world, with its pleasures and attachments, was transient and that true happiness could only be achieved through renunciation and spiritual discipline. His renunciation marked the beginning of a life of extreme austerity and meditation, leading him on a journey to discover the eternal truths of existence.

Mahavira’s early life was marked by the internal conflict between the duties of a prince and the pull toward asceticism. Eventually, his spiritual calling triumphed, setting the stage for his journey toward enlightenment and the spread of his teachings. This renunciation would later serve as the foundation for his significant contributions to Jainism and Indian spiritual thought.

The Path of Renunciation and Asceticism

Upon renouncing his royal life, Mahavira embarked on a life of rigorous asceticism. At the age of 30, he left behind his family, wealth, and comforts to seek the truth of existence through self-discipline, meditation, and detachment from worldly desires. He embraced the life of an ascetic, dedicating himself to the practice of extreme austerity.

Mahavira practiced non-violence (Ahimsa), non-attachment (Aparigraha), and truthfulness (Satya) as key principles of his asceticism. He wandered through forests and villages, enduring physical hardships and remaining indifferent to the comforts of life. He practiced deep meditation, even under harsh conditions, and maintained silence (Mauna) for long periods, reflecting his detachment from worldly distractions.

For twelve years, Mahavira wandered as a solitary ascetic, rejecting all forms of material comfort. He faced countless challenges, including physical discomfort, extreme weather conditions, and even the hostility of people who did not understand his path. Despite these hardships, he remained steadfast in his commitment to self-discipline and spiritual progress.

One of the central practices during this period was fasting. Mahavira practiced severe fasting, sometimes going without food or water for extended periods, to purify his mind and body. He believed that such practices helped to overcome the passions and desires that bind individuals to the cycle of birth and death (Samsara).

In his quest for liberation (Moksha), Mahavira adhered to the principle of Ahimsa with extreme rigor. This non-violence extended not only to human beings but to all living creatures. He carefully avoided causing harm to any form of life, whether it be insects, animals, or plants. His commitment to Ahimsa became one of the most significant contributions to Jain philosophy and a cornerstone of his teachings.

During his period of asceticism, Mahavira followed the path laid down by previous Tirthankaras, especially Parshvanatha. However, Mahavira refined and expanded these teachings, emphasizing the importance of complete renunciation and non-violence in every aspect of life. His teachings would later form the foundation of Jainism as it is known today.

After twelve years of rigorous asceticism, Mahavira attained Kevala Jnana, or omniscience, under a Sal tree in the village of Jrimbhikagrama. This enlightenment marked the culmination of his spiritual journey, as he realized the ultimate truths of the universe and transcended the cycle of birth and death. From this moment on, Mahavira became known as the Jina, or conqueror, and dedicated the rest of his life to spreading his teachings of non-violence, truth, and renunciation.

Teachings and Philosophy

Mahavira’s teachings form the core of Jainism, a religion that emphasizes non-violence, truth, and asceticism. His philosophy is deeply rooted in the principles of Ahimsa (non-violence), Anekantavada (non-absolutism), and Aparigraha (non-possession), which guide the moral and ethical conduct of Jain followers.

Ahimsa, or non-violence, is the central tenet of Mahavira’s teachings. He believed that all living beings, no matter how small or insignificant, possess a soul and are entitled to live without fear of harm. This principle of non-violence extends beyond physical actions to include thoughts and words. Mahavira emphasized that violence in any form, whether intentional or unintentional, leads to the accumulation of negative karma, which binds the soul to the cycle of rebirth.

Mahavira expanded the concept of Ahimsa to include not only humans and animals but also plants, microorganisms, and even the elements of nature. For him, the protection of life in all its forms was a sacred duty, and this belief is reflected in the strict vegetarianism and environmental consciousness observed by Jain communities.

Anekantavada, or non-absolutism, is another key aspect of Mahavira’s philosophy. This doctrine teaches that reality is complex and multifaceted, and no single perspective can fully capture the truth. According to Mahavira, every viewpoint is valid from its own perspective, and understanding the full truth requires considering multiple perspectives. This principle of non-absolutism fosters tolerance and open-mindedness, encouraging individuals to respect different opinions and beliefs.

Aparigraha, or non-possession, is the third pillar of Mahavira’s teachings. He believed that attachment to material possessions creates desires and cravings that bind the soul to the cycle of birth and death. By practicing non-possession, individuals can free themselves from the bondage of materialism and achieve spiritual liberation. Aparigraha also promotes a simple and contented lifestyle, where one’s needs are minimized, and the focus is on inner growth rather than external accumulation.

Mahavira’s teachings are encapsulated in the Five Great Vows (Mahavratas), which are the foundation of Jain ethical conduct:

- Ahimsa: Non-violence in thought, word, and deed.

- Satya: Truthfulness in speech and actions.

- Asteya: Non-stealing, or not taking anything that is not willingly offered.

- Brahmacharya: Celibacy or chastity, which includes control over one’s desires and passions.

- Aparigraha: Non-attachment to material possessions and relationships.

These Five Vows are observed by both Jain monks and lay followers, though the level of observance differs. Monks and nuns follow these vows with extreme rigor, while laypeople are encouraged to practice them to the best of their ability in their daily lives.

Mahavira also taught the doctrine of karma, which holds that every action, whether good or bad, has consequences that affect the soul. The accumulation of karma binds the soul to the cycle of Samsara, or rebirth, and the only way to achieve liberation is by purifying the soul through right conduct, knowledge, and meditation.

Mahavira’s teachings emphasized self-discipline, mindfulness, and compassion as essential elements of the spiritual path. He believed that by practicing these principles, individuals could attain Kevala Jnana, or omniscience, and ultimately achieve Moksha, the liberation of the soul from the cycle of birth and death.

Spread of Jainism and Mahavira’s Disciples

After attaining enlightenment, Mahavira spent the remaining 30 years of his life spreading his teachings across the Indian subcontinent. He traveled extensively, accompanied by a group of disciples, delivering sermons and establishing monastic orders. His teachings attracted a wide following, and he is credited with organizing the Jain community into a structured religious order.

Mahavira’s followers were divided into two main groups: monks and laypeople. The monks, also known as ascetics, took rigorous vows of renunciation and followed strict rules of conduct. They dedicated their lives to the pursuit of spiritual liberation through meditation, austerity, and self-discipline. The laypeople, while not renouncing worldly life, were encouraged to follow the Five Great Vows to the best of their ability and support the monastic community.

Mahavira’s teachings were spread through the efforts of his eleven chief disciples, known as the Ganadharas. These Ganadharas were highly learned and spiritually advanced monks, and they played a crucial role in spreading Mahavira’s teachings across various regions of India. The most prominent among them was Indrabhuti Gautama, who later became Mahavira’s first disciple. Indrabhuti was initially a scholar with doubts about Mahavira’s teachings but was deeply influenced by Mahavira’s wisdom and eventually accepted Jainism.

Mahavira’s ability to attract a diverse range of followers contributed to the spread of Jainism across the subcontinent. His disciples included people from different walks of life—royalty, merchants, scholars, and common people—all drawn by the promise of liberation and the emphasis on ethical conduct. Mahavira encouraged people to practice his teachings in accordance with their capacity, making Jainism accessible to both ascetics and householders.

Jainism’s appeal extended to women as well, which was significant in a society where religious practice was often male-dominated. Mahavira established a monastic order for women, who took vows of renunciation and lived as nuns under the guidance of female leaders. This inclusivity helped Jainism gain a broad following and played a part in the religion’s resilience over the centuries.

Mahavira’s influence wasn’t limited to religious teachings alone. His emphasis on non-violence and compassion had social and political ramifications as well. Jain kings and rulers who adopted his teachings implemented policies that reflected the principles of Ahimsa and Anekantavada. For instance, many Jain rulers promoted vegetarianism, animal welfare, and tolerance toward other faiths, helping to create a more peaceful and harmonious society.

The organization of the Jain community during Mahavira’s lifetime laid the foundation for the religion’s longevity. He established a structured monastic order known as the Sangha, which consisted of monks (Sadhus), nuns (Sadhvis), and lay followers (Shravakas and Shravikas). The Sangha became the institution through which Jainism was preserved and transmitted across generations. Mahavira’s disciples played a pivotal role in organizing this community and ensuring that his teachings were passed down accurately through oral tradition.

The spread of Jainism was not without challenges. Mahavira and his followers faced opposition from orthodox Brahminical traditions, which resisted the egalitarian and ascetic ideals of Jainism. Despite this, Mahavira’s teachings continued to spread due to his charisma, the dedication of his disciples, and the profound appeal of his message of non-violence and liberation.

After 30 years of teaching and traveling, Mahavira attained Nirvana at the age of 72 in 527 BCE in the town of Pava, near modern-day Patna, Bihar. His death is commemorated as Diwali by Jains, a festival that marks not only the end of Mahavira’s earthly journey but also the attainment of eternal bliss and liberation from the cycle of birth and death.

Following his Nirvana, Mahavira’s teachings were preserved by his disciples, particularly Indrabhuti Gautama, who became the head of the Jain Sangha. Jainism continued to flourish, with the teachings being passed down through generations of monks and lay followers. The oral tradition eventually gave way to written scriptures, ensuring that Mahavira’s teachings were codified and preserved for future generations.

The legacy of Mahavira’s teachings and the Jain community he established would go on to shape Indian culture and spirituality in significant ways, influencing not only Jainism but also other religious traditions such as Buddhism and Hinduism. His teachings on non-violence, in particular, resonated deeply and had a profound impact on figures like Mahatma Gandhi, who adopted Ahimsa as a guiding principle in the struggle for Indian independence.

Jain Scriptures and the Preservation of Mahavira’s Teachings

After Mahavira’s Nirvana, his teachings were preserved through oral transmission by his disciples and later compiled into Jain scriptures. This process of preserving and codifying the teachings was critical to maintaining the integrity of Jainism and ensuring that Mahavira’s message could be passed down to future generations.

The early Jain scriptures, known as the Agamas, are believed to be the direct teachings of Mahavira, as remembered by his disciples, particularly Indrabhuti Gautama. These scriptures cover a wide range of topics, including ethical conduct, metaphysics, cosmology, and the path to liberation. The Agamas were originally transmitted orally, following the tradition of recitation and memorization. This oral tradition was maintained for several centuries before the scriptures were eventually written down.

The process of compiling the Jain scriptures was complex and occurred over several centuries. The earliest written versions of the Agamas were composed in Prakrit, an ancient Indian language that was accessible to a broader audience compared to Sanskrit, the language of the Vedic texts. This linguistic choice reflects Jainism’s emphasis on inclusivity and its appeal to people from diverse backgrounds.

The compilation of the Jain scriptures was not without challenges. Over time, different sects of Jainism emerged, leading to variations in the scriptural canon. The two main sects of Jainism, the Digambaras and the Svetambaras, have slightly different interpretations of Mahavira’s teachings, and this is reflected in their respective scriptural traditions.

The Svetambaras, who wear white robes, believe that the Agamas contain the authentic teachings of Mahavira and have preserved a collection of 45 scriptures that form the basis of their religious practices. The Digambaras, who practice more austere asceticism, including the practice of nakedness, believe that the original Agamas were lost over time and that their current scriptures are based on later interpretations of Mahavira’s teachings.

Despite these differences, both sects agree on the core principles of Jainism, such as non-violence, truth, non-attachment, and the pursuit of liberation. The preservation of Mahavira’s teachings through these scriptures has ensured that Jainism remains a vibrant and living tradition, with millions of followers around the world who continue to practice his teachings in their daily lives.

In addition to the Agamas, Jain literature also includes a vast body of philosophical and ethical texts written by later scholars and monks. These texts delve deeper into Mahavira’s teachings, offering commentaries and interpretations that help followers understand and apply Jain principles in different contexts. Some of the most important texts in Jain literature include the Tattvartha Sutra, a comprehensive summary of Jain philosophy, and the Kalpasutra, which recounts the life of Mahavira and other Tirthankaras.

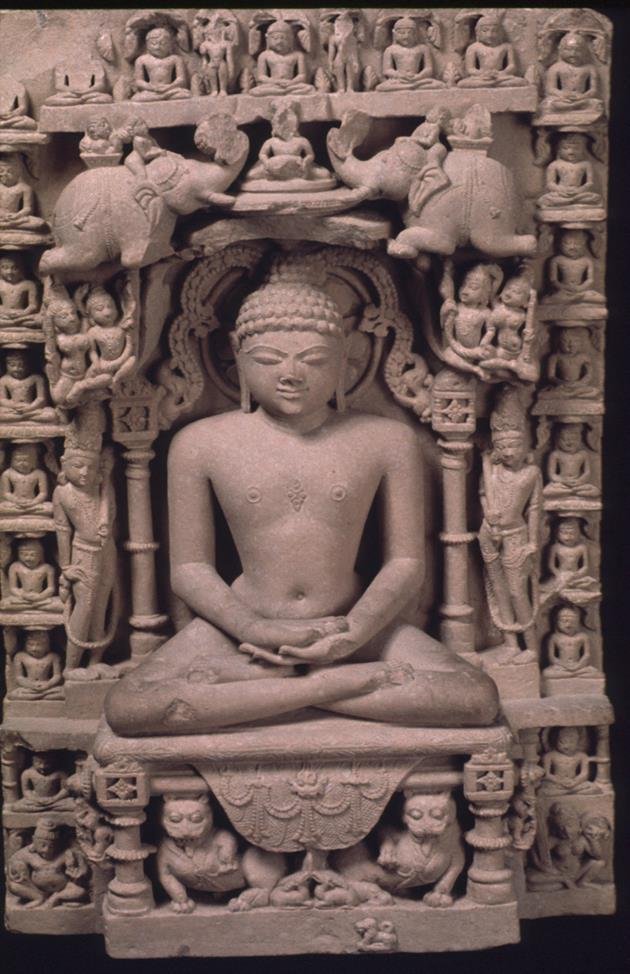

The preservation of Jain teachings has not only been a religious endeavor but also a cultural and artistic one. Jain temples, manuscripts, and art have played a significant role in preserving the religion’s heritage. Jain temples, with their intricate carvings and architectural grandeur, often depict scenes from the life of Mahavira and other Tirthankaras, serving as visual representations of Jain teachings. Jain manuscripts, written on palm leaves and adorned with delicate illustrations, are prized for their beauty and historical significance.

Through the efforts of monks, scholars, artists, and laypeople, Mahavira’s teachings have been preserved and transmitted across generations, allowing Jainism to thrive as one of the world’s oldest living religions. The emphasis on non-violence, respect for all forms of life, and the pursuit of spiritual liberation remains central to Jain practice, reflecting the enduring legacy of Mahavira’s life and teachings.

Mahavira’s Legacy and Influence on Indian Thought

Mahavira’s influence extends far beyond the Jain community, impacting Indian culture, philosophy, and spirituality in profound ways. His teachings on non-violence, compassion, and respect for all forms of life have resonated across religious boundaries, shaping the moral and ethical landscape of India for centuries.

One of the most significant aspects of Mahavira’s legacy is his contribution to the concept of Ahimsa, or non-violence, which became a cornerstone of not only Jainism but also other Indian religious traditions, including Buddhism and Hinduism. The idea of non-violence as a moral and ethical imperative was revolutionary in a society that, at the time, was often marked by violence and conflict. Mahavira’s insistence on the sanctity of all life and the need to avoid harm in thought, word, and deed inspired generations of spiritual leaders and thinkers.

Ahimsa became a guiding principle for Mahatma Gandhi in his non-violent struggle for India’s independence from British rule. Gandhi’s adoption of non-violence as both a personal ethic and a political strategy was deeply influenced by Jainism, particularly the teachings of Mahavira. Gandhi often referred to Ahimsa as the highest moral virtue, and he credited Jainism with shaping his understanding of compassion and ethical living. Through Gandhi, Mahavira’s teachings on non-violence gained global recognition and influenced movements for social justice and peace around the world.

Beyond non-violence, Mahavira’s emphasis on Anekantavada, or non-absolutism, has contributed to the development of pluralistic thought in India. The idea that reality is complex and multifaceted, and that no single viewpoint can capture the full truth, has encouraged a culture of tolerance and intellectual humility. This philosophical outlook has allowed for the coexistence of diverse religious traditions in India and has fostered dialogue and understanding among different communities.

Mahavira’s teachings on non-attachment and asceticism have also left a lasting impact on Indian spiritual practices. His advocacy for Aparigraha, or non-possession, has influenced the monastic traditions of various Indian religions, including Buddhism and Hinduism. The ideal of renunciation, as a path to spiritual liberation, is a common theme in Indian spirituality, and Mahavira’s life serves as a model for those seeking to transcend worldly attachments in pursuit of higher truths.

Mahavira’s legacy extends into the cultural and artistic realms as well. Jain art, architecture, and literature are significant contributions to Indian heritage, reflecting the profound impact of his teachings. Jain temples, with their intricate carvings and elaborate structures, often depict scenes from Mahavira’s life and the lives of other Tirthankaras. These temples not only serve as places of worship but also as repositories of Jain history and philosophy.

The Jain tradition of manuscript preservation has resulted in a wealth of historical and philosophical texts that continue to be studied and revered. Jain manuscripts, written in ancient languages and adorned with detailed illustrations, are considered valuable cultural artifacts. They offer insights into the religious and intellectual life of ancient India and have been crucial in maintaining the continuity of Jain thought.

Mahavira’s influence is also evident in the broader Indian philosophical tradition. His ideas on non-violence, truth, and ethical living have been incorporated into various philosophical schools and have inspired many Indian thinkers. The principles of Jainism, particularly Ahimsa and Anekantavada, have contributed to the development of Indian ethics and metaphysics, shaping the discourse on morality, reality, and human conduct.

In modern times, Jainism continues to thrive as a vibrant and dynamic tradition. The global Jain community actively promotes the principles of Mahavira through education, social service, and interfaith dialogue. Jain organizations and temples around the world work to preserve Mahavira’s teachings and apply them to contemporary issues, such as environmental conservation, animal rights, and social justice.

Mahavira’s life and teachings remain a source of inspiration for millions. His dedication to non-violence, his commitment to truth, and his pursuit of spiritual liberation offer timeless lessons on how to live a meaningful and ethical life. As a revered spiritual leader and reformer, Mahavira’s impact on Indian culture and spirituality endures, demonstrating the lasting relevance of his message in today’s world.

Mahavira’s legacy, therefore, is not just a historical phenomenon but a living tradition that continues to influence and inspire people across cultures and generations. His teachings serve as a reminder of the power of compassion, the importance of ethical conduct, and the pursuit of spiritual enlightenment, making him a timeless figure in the history of human thought.