Human beings have always told stories to explain the mysteries of existence—why the sun rises and sets, why rivers flow, why joy and sorrow walk hand in hand. Among these ancient tales, one stands out with particular resonance: the story of Pandora’s Box. This Greek myth has echoed through centuries, retold in poetry, paintings, philosophy, and psychology. It is not merely a tale of gods and mortals; it is an allegory of human curiosity, the burden of suffering, and the flickering light of hope that refuses to be extinguished.

Though told and retold in different forms, the essence of the myth remains the same: Pandora, the first woman, opens a container forbidden to her, and in doing so unleashes the evils that afflict humanity. This moment becomes not only the origin of human misfortune but also a mirror of human nature itself. To understand Pandora’s Box is to look deeply into the heart of what it means to live, to err, to endure, and to hope.

The Birth of Pandora

The story of Pandora begins not with her, but with a theft. According to Greek mythology, the Titan Prometheus defied the mighty Zeus, ruler of the gods, by stealing fire from Olympus and gifting it to humankind. Fire was more than a tool; it was a symbol of knowledge, technology, and independence. With fire, humans no longer depended entirely on divine mercy. They could cook food, forge metal, light the dark, and warm themselves against the cold.

But to Zeus, Prometheus’s act was unforgivable. It was not only defiance but also empowerment of mortals who, in his eyes, should remain weak and dependent. Enraged, Zeus sought punishment—not only for Prometheus but for all humanity who benefitted from his rebellion.

Thus, Pandora was created. Crafted by Hephaestus, the god of fire and forge, from clay and water, she was molded into breathtaking beauty. Each Olympian god bestowed upon her a gift: Athena gave her wisdom and skill, Aphrodite gave her charm and desire, Hermes granted her cunning, and the Graces adorned her with elegance. But hidden within these blessings was a curse, for she was designed as both a wonder and a snare. Her very name, Pandora, means “all-gifted.” Yet the gifts carried consequences.

Zeus offered Pandora as a bride to Epimetheus, Prometheus’s brother. Despite warnings never to accept a gift from Zeus, Epimetheus was enchanted by Pandora’s beauty and took her into his home. With Pandora came a jar—later mistranslated as a box—sealed tightly and left in her possession.

The Forbidden Jar

The jar Pandora carried was no ordinary vessel. It was heavy with divine intention, brimming with mysteries hidden from mortal eyes. Though instructed never to open it, the jar called to her curiosity. The gods had built into her both intelligence and a restless spirit. In this lies one of the most human aspects of her tale: the irresistible pull of curiosity.

For days, perhaps months, Pandora lived with the jar, resisting its lure. Yet, as many myths show, human curiosity is a force as powerful as love or hunger. One day, she lifted the lid.

From the jar burst forth a whirlwind of horrors. Pain, disease, envy, greed, anger, sorrow, toil, famine, death—all the afflictions that plague humanity—escaped into the world. Once released, they could not be recalled. What had been a world of relative peace was now marred by hardship and suffering.

In terror, Pandora slammed the lid shut. But it was too late. Only one thing remained inside the jar: Hope.

The Role of Hope

The ending of the myth is one of its most debated elements. What does it mean that Hope stayed behind? Was it withheld from humanity, trapped forever within the jar, or was it preserved as a gift for mortals to endure the evils loosed upon them?

Many interpretations exist. Some philosophers argue that Hope’s entrapment was cruel, denying humans the one balm against suffering. Others suggest that Hope remained not as a denial but as a safeguard, dwelling within human hearts as the final blessing, enabling endurance amidst suffering.

In this ambiguity lies the genius of the myth. Hope is both fragile and powerful. It can sustain through despair, but it can also deceive, luring with promises that may never be fulfilled. The myth leaves us questioning whether Hope is a blessing or another subtle curse.

Pandora as the First Woman

Pandora’s story cannot be separated from its cultural context. She was the first mortal woman in Greek mythology, created not as a companion but as a punishment. This places her tale within a tradition of myths that portray women as the bringers of trouble, temptation, or downfall—a theme seen across cultures, from Eve in the Garden of Eden to other archetypes of feminine transgression.

In Pandora, we see the anxieties of ancient Greece about women’s role in society. She embodied beauty, intelligence, and charm, but also deception, curiosity, and danger. Her myth reflects patriarchal fears about women’s independence and power. To the Greeks, Pandora symbolized both irresistible attraction and inevitable misfortune.

Yet modern interpretations have reclaimed her story. Rather than viewing her as a curse, some see her as a symbol of human curiosity, creativity, and agency. Without Pandora’s act, humanity would have remained in ignorant bliss, untouched but also stagnant. By opening the jar, she did not merely unleash suffering; she awakened the full range of human experience.

The Jar or the Box?

An intriguing twist in Pandora’s myth lies in the mistranslation that shaped its retelling. The original Greek word used in Hesiod’s writings was pithos, meaning a large storage jar or urn. Such jars were common in Greek households for storing grain, oil, or wine. But when the Renaissance scholar Erasmus translated the story into Latin, he used the word pyxis, meaning a small box. From then on, the myth became known as “Pandora’s Box.”

This small error transformed the image of the myth. A jar is domestic, earthy, and functional, while a box is mysterious, personal, and secretive. The phrase “Pandora’s Box” became a metaphor in Western culture for a seemingly small action that unleashes vast and uncontrollable consequences. Though the detail may have been accidental, it shaped centuries of art, literature, and philosophy.

The Psychological Dimensions

Beyond mythology, Pandora’s Box has entered the realm of psychology and human behavior. The myth can be read as an allegory of curiosity and consequence—the tension between the desire to know and the fear of what knowledge may bring.

Sigmund Freud and later psychologists viewed Pandora’s tale as symbolic of human impulses. The forbidden jar becomes a metaphor for the unconscious mind, holding both repressed desires and hidden fears. Opening it is akin to confronting what is buried within ourselves.

Modern psychology also recognizes the myth as a reflection of resilience. While suffering is inevitable, the presence of Hope—whether seen as real or illusory—demonstrates humanity’s ability to endure. Pandora’s Box becomes not just a story of downfall but also of survival.

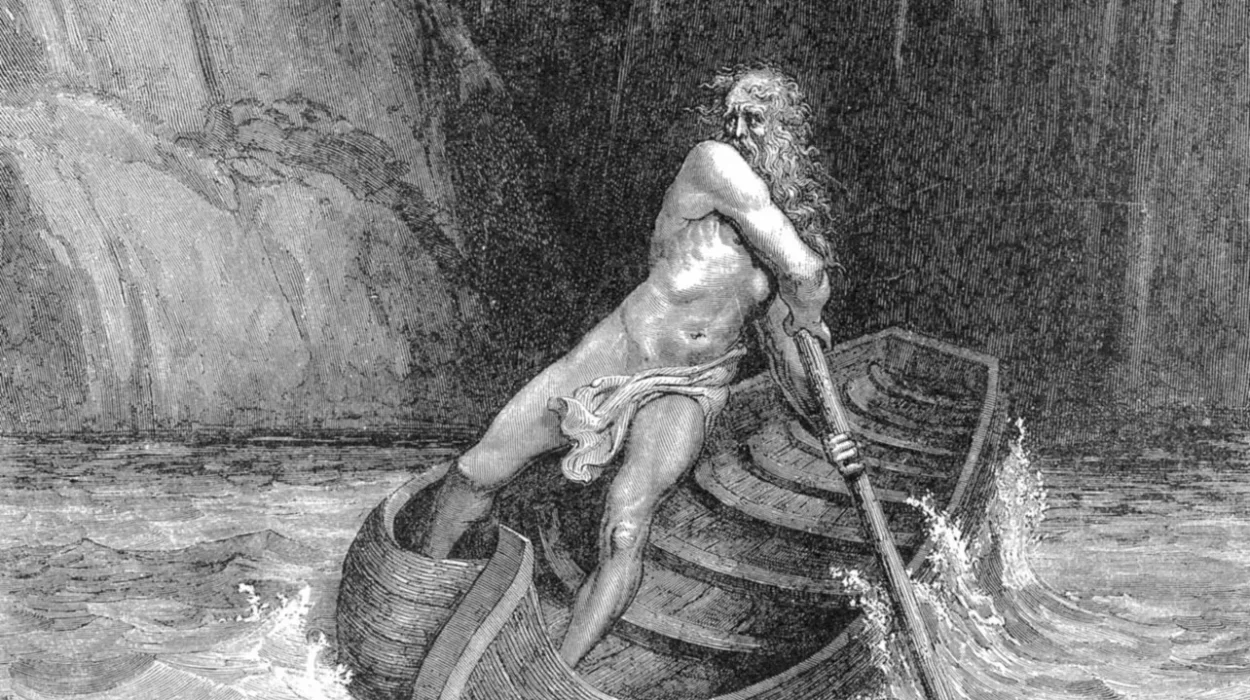

Pandora’s Box in Literature and Art

From ancient pottery to modern novels, Pandora’s Box has captivated artists and writers. In Hesiod’s Works and Days, the earliest account, the myth is told with a tone of warning. Later, dramatists and poets expanded her role, turning her into both a symbol of doom and a figure of tragic beauty.

During the Renaissance, painters often depicted Pandora as a radiant woman, poised in the moment of lifting the lid, her face a mixture of wonder and fear. Romantic poets like John Keats and Percy Bysshe Shelley wove her into their verses, seeing in her both danger and inspiration.

In modern literature, the phrase “Pandora’s Box” has become shorthand for unintended consequences. It appears in novels, films, and political commentary whenever human ambition or curiosity unleashes forces beyond control. From nuclear weapons to artificial intelligence, the metaphor is invoked again and again.

Scientific and Ethical Echoes

Though born of myth, Pandora’s Box resonates deeply with modern science and ethics. Every major technological breakthrough carries the potential for both benefit and disaster. When scientists split the atom, they opened a Pandora’s Box of nuclear power—capable of both electricity and annihilation. Genetic engineering, artificial intelligence, and climate manipulation are similarly described as boxes that, once opened, cannot be closed.

The myth remains a cautionary tale: human curiosity must be balanced with responsibility. To explore and discover is natural, but to do so without foresight risks releasing forces we cannot control. Pandora’s Box reminds us that knowledge is powerful, but wisdom is essential.

A Universal Archetype

What makes Pandora’s Box endure is not only its beauty as a story but its universality. Nearly every culture has a myth of forbidden knowledge, temptation, or a single act that changes the world forever. Eve eating the fruit in Eden, the release of chaos in Mesopotamian myth, the tales of trickster gods—they all echo Pandora’s act.

These stories reveal something deeply human: our desire to understand, to push boundaries, and to explore the unknown, even when warned of the consequences. Pandora is not a villain but a reflection of ourselves. Her curiosity, her mistake, and her legacy are profoundly human traits.

The Feminine Principle of Change

If we look more closely, Pandora is not only the bringer of evils but the bringer of change. Before her, the world of humans was static—fire was stolen, but life remained simple. After her, humanity entered a world of complexity, struggle, and growth.

Suffering, though tragic, also creates resilience. Hardship teaches compassion, endurance, and innovation. Without disease, there would be no healing arts. Without conflict, no justice. Without sorrow, no appreciation of joy.

In this light, Pandora becomes not a curse but a catalyst. She is the spark that propels humanity from innocence into experience, from ignorance into wisdom.

The Enduring Legacy of the Myth

Today, the phrase “opening Pandora’s Box” instantly conjures the idea of small actions unleashing great consequences. Politicians use it, scientists warn of it, and artists draw upon it. Yet beneath the cliché lies a myth still vibrant, still rich with meaning.

Pandora’s story continues to evolve, shaped by each generation’s fears and hopes. In a world facing climate change, technological upheaval, and global uncertainty, the myth feels more relevant than ever. Humanity stands at countless thresholds, holding jars filled with possibilities both wondrous and dangerous.

And yet, in every retelling, one truth remains: at the bottom of the jar, after all the sorrows, after all the evils, Hope waits.

Pandora and the Human Condition

In the end, Pandora’s Box is not just a story about gods punishing mortals. It is a reflection of the human condition itself. We are creatures of boundless curiosity, often reckless, often blind to consequences. We unleash problems we cannot foresee. Yet we also endure.

The myth tells us that suffering is part of life, but so is resilience. That curiosity brings danger, but also progress. That even when the world seems darkened by evils, a spark of hope endures.

Pandora’s Box is our story—of mistakes and endurance, of sorrow and strength, of despair and hope. It reminds us that to be human is to live in a world forever changed by our choices, but never without the possibility of light.