Among the countless myths of ancient Greece, few gleam as brightly as the story of Perseus and the slaying of Medusa. It is a tale carved into the bedrock of Western imagination, passed down for thousands of years in poetry, sculpture, and whispered legend. It is the story of a young hero born into peril, armed with divine gifts, and sent on an impossible mission against a monstrous being whose very gaze turned men into stone.

This is no mere bedtime story. It is a myth that pulses with the essence of ancient Greek culture—the tension between mortality and divinity, the weight of fate, the cunning of gods, and the fragile yet unyielding courage of a human being standing before the abyss. The myth of Perseus is at once a coming-of-age narrative, a meditation on destiny, and an allegory for the triumph of ingenuity over chaos.

To dive into the story of Perseus and Medusa is to wander into the very heart of Greek mythology, where the boundary between human and divine blurs and where monsters are not just creatures of nightmare but symbolic mirrors of humanity’s deepest fears.

The Birth of Perseus: A Child of Fate

The story of Perseus begins not with the hero himself, but with his grandfather, King Acrisius of Argos. Acrisius was a ruler troubled by prophecy. The Oracle of Delphi, that enigmatic voice of destiny, foretold that he would one day be slain by his daughter’s son. Fearful of losing his life, Acrisius sought to defy fate. He locked his daughter, Danaë, in a bronze chamber beneath the earth—a prison of shining metal designed to prevent her from ever bearing a child.

But in Greek myth, no mortal barrier could resist the will of the gods. Zeus, king of Olympus, saw Danaë and was enchanted by her beauty. Transforming himself into a shower of golden light, he descended through the bronze walls and into her chamber. From this divine union, Perseus was conceived—a child born not in freedom, but in captivity, destined to fulfill a prophecy that had already sealed his grandfather’s fate.

When Acrisius discovered the infant, terror gripped him. Yet he dared not spill the blood of his own kin, for the ancient Greeks believed such an act would draw down divine wrath. Instead, he placed Danaë and the child in a wooden chest and cast them into the sea, leaving fate to decide their end.

But the sea, though vast and merciless, was also under the watch of the gods. The chest drifted to the island of Seriphos, where it was found by a kind fisherman named Dictys. He brought mother and child ashore, raising Perseus as his own and setting the stage for the hero’s destiny.

The Shadow of Polydectes

On Seriphos, Perseus grew into a young man of remarkable strength and courage. But his peaceful life did not last. Dictys’s brother, King Polydectes, grew lustful for Danaë. She, however, resisted his advances. Enraged, Polydectes devised a plan to rid himself of the son who stood between him and his desires.

Polydectes announced a grand banquet, declaring that each guest must bring a gift fit for a king. Perseus, poor and without wealth, had nothing to offer. Mocked and pressured, he swore that he would bring back the head of Medusa, one of the terrifying Gorgons whose gaze could turn flesh to stone.

The court laughed at this boast, for no man had ever faced Medusa and lived. But Polydectes seized upon it. He demanded Perseus make good on his promise, sending him on what seemed a death sentence. To survive, Perseus would need more than strength—he would need the favor of the gods themselves.

The Monster Known as Medusa

Before following Perseus’s journey, it is worth pausing to understand the terror that awaited him. Medusa was one of the three Gorgon sisters, born of ancient, primal deities. Unlike her immortal siblings, Medusa was mortal, and thus vulnerable. Yet she was the most feared of them all.

In early Greek tradition, the Gorgons were described as monstrous beings with scales, wings, tusks, and serpents for hair. Later retellings softened Medusa’s image, painting her as a tragic figure—a beautiful maiden cursed by Athena for being violated in her temple by Poseidon. Her punishment was cruel: her hair transformed into writhing snakes, her face into a mask of horror, and her gaze imbued with the power to petrify.

Thus Medusa became a symbol of both terror and sorrow. She was not just a monster to be slain but an embodiment of divine wrath, injustice, and the fragility of mortal beauty under the shadow of gods.

For Perseus to confront Medusa was to stand before the ultimate test: to face the very image of death itself.

The Divine Allies

In Greek mythology, heroes are never alone. They walk with the aid of gods, for no mortal can defeat monsters born of chaos unaided. For Perseus, salvation came in the form of Athena, goddess of wisdom and war, and Hermes, messenger of the gods.

Athena guided him to the path he must take, while Hermes gifted him a curved blade sharp enough to cut through stone and scale. To find Medusa, Perseus first had to seek the Graeae—three ancient sisters who shared a single eye between them. By cunning, he seized their eye and forced them to reveal the way to the Nymphs of the North, guardians of items crucial for his quest.

From the Nymphs, Perseus received three sacred gifts:

- A cap of invisibility, to conceal him from Medusa’s sisters.

- A polished bronze shield, not just for defense but as a mirror, so he could avoid her deadly gaze.

- A magical pouch, capable of holding Medusa’s severed head without harm.

Armed with these treasures and guided by divine will, Perseus embarked on the most perilous journey of his life.

The Slaying of Medusa

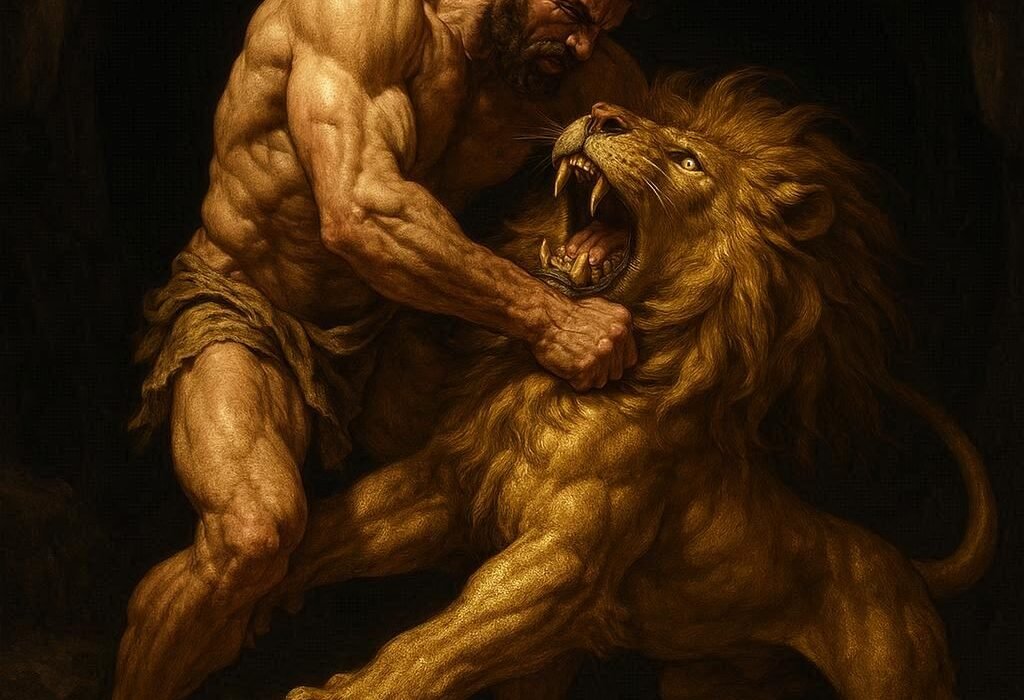

The moment came at last when Perseus entered the lair of the Gorgons, a place shrouded in terror. There lay Medusa, her serpent hair hissing, her breath echoing like wind in a cavern. Around her stood the statues of warriors and creatures who had once dared to face her, their final moments frozen in stone.

To look upon Medusa directly was death. Perseus, remembering Athena’s counsel, lifted his bronze shield and gazed only at her reflection. Step by careful step, he approached. His heart thundered, for even in reflection, Medusa’s visage was terrifying.

With Hermes’s blade raised high, Perseus struck. The sword severed her neck in one swift motion, and from the wound leapt forth Pegasus, the winged horse, and Chrysaor, a warrior born fully armed. They were the children of Poseidon and Medusa, released at the moment of her death.

Quickly, Perseus placed the head into his pouch. But Medusa’s immortal sisters awoke in fury, their cries shaking the earth. Donning his cap of invisibility, Perseus vanished from their sight, escaping into the shadows of the world with his prize.

The impossible had been achieved. Perseus had slain the monster that none before him could face.

The Journey Home

Yet Perseus’s story did not end with Medusa’s death. The journey home became a tale in itself, filled with trials that further tested the hero’s courage.

On his way back, he encountered the Titan Atlas, who bore the weight of the heavens upon his shoulders. When Atlas, weary of prophecy, denied him shelter, Perseus revealed the head of Medusa. At once, Atlas was turned into a towering mountain, his body forming the very Atlas range that still stands today.

Further still, Perseus came upon the coast of Ethiopia, where the maiden Andromeda was chained to a rock as sacrifice to a sea monster. Her mother, Queen Cassiopeia, had boasted that her daughter’s beauty surpassed that of the Nereids, enraging Poseidon, god of the sea. In wrath, he sent a beast to ravage the land.

Perseus, moved by her plight, swooped down from the sky. With Medusa’s head as weapon, he turned the monster into stone, rescuing Andromeda. In gratitude, the two were wed, and Andromeda became his queen—a union that bound heroism with love.

The Return to Seriphos

When Perseus finally returned to Seriphos, he found his mother still tormented by King Polydectes. The tyrant had long believed Perseus would never return, yet now the hero stood before him with proof of his triumph.

In the great hall of the court, Perseus revealed Medusa’s head. Polydectes and his followers, mocking one moment, were stone the next. Justice had been served, not through swordplay, but through the very terror the king had sent Perseus to face.

Perseus then placed Dictys, the kind fisherman who had saved him as a child, upon the throne of Seriphos. At last, his mother was free, and the cycle of tyranny was broken.

Fate Fulfilled

The prophecy of Acrisius, however, still loomed in the background. Despite all his victories, Perseus could not escape destiny. Years later, during athletic games in Larissa, he accidentally killed his grandfather with a discus, fulfilling the oracle’s words.

Thus the myth of Perseus closes with a reminder of one of Greek mythology’s deepest truths: no matter how mighty a hero may be, no one escapes the hand of fate.

Symbolism and Legacy

The story of Perseus and Medusa is not merely an adventure tale. It is layered with meaning that has echoed through centuries:

- Perseus represents courage, wit, and divine favor working together against impossible odds.

- Medusa, once a maiden, cursed and demonized, represents both the terror of the unknown and the injustice of divine punishment.

- The head of Medusa itself became a protective symbol, the Gorgoneion, placed upon shields, armor, and temples to ward off evil.

Artists, poets, and sculptors across millennia have been captivated by this myth. From ancient vase paintings to Renaissance masterpieces, the image of Perseus standing triumphant with Medusa’s head remains one of the most iconic symbols of Greek mythology.

Even today, Medusa’s face appears in art, fashion, and literature. She has been reinterpreted not only as a monster but also as a symbol of feminine rage, resilience, and power. Perseus, likewise, embodies the eternal human struggle against fear, chaos, and the shadows within ourselves.

The Timeless Power of Myth

The myth of Perseus and Medusa endures because it touches something universal. It speaks to the fear of death, the hope of courage, and the belief that even the most terrifying trials can be overcome with ingenuity and strength.

It is a story that has been told for over two thousand years, yet it still feels alive. Each retelling breathes new meaning into its characters. Perseus is not just a hero of ancient Greece—he is every human who dares to face the unfaceable. Medusa is not only a monster of the past—she is every terror that looms in the dark, waiting for us to confront it.

In the end, the myth is not about gods or monsters, but about humanity itself. It is about standing before the gaze of death and refusing to turn to stone.