In the Four Corners region of the American Southwest, where Colorado, Utah, Arizona, and New Mexico meet, the sun blazes down upon windswept mesas, sheer cliffs, and ancient ruins etched with secrets. Here, the canyons whisper stories of a once-great civilization—the Ancestral Puebloans—who flourished in this unforgiving landscape for centuries, only to vanish in one of history’s most intriguing disappearances.

The Ancestral Puebloans, often referred to as the Anasazi (a Navajo term that has fallen out of favor due to its controversial meaning), left behind stunning architectural feats: massive stone dwellings, ceremonial chambers called kivas, intricate road systems, and cliffside villages carved with breathtaking precision. Yet by the end of the 13th century, these people who had transformed desert into home had all but disappeared from their central heartlands.

What led to their exodus? Where did they go? And why does their story continue to captivate historians, archaeologists, and modern-day descendants alike?

Let’s journey through time and terrain, piecing together the complex narrative of a people who shaped an entire region—and then walked away from it.

The Rise of a Civilization in Stone and Sky

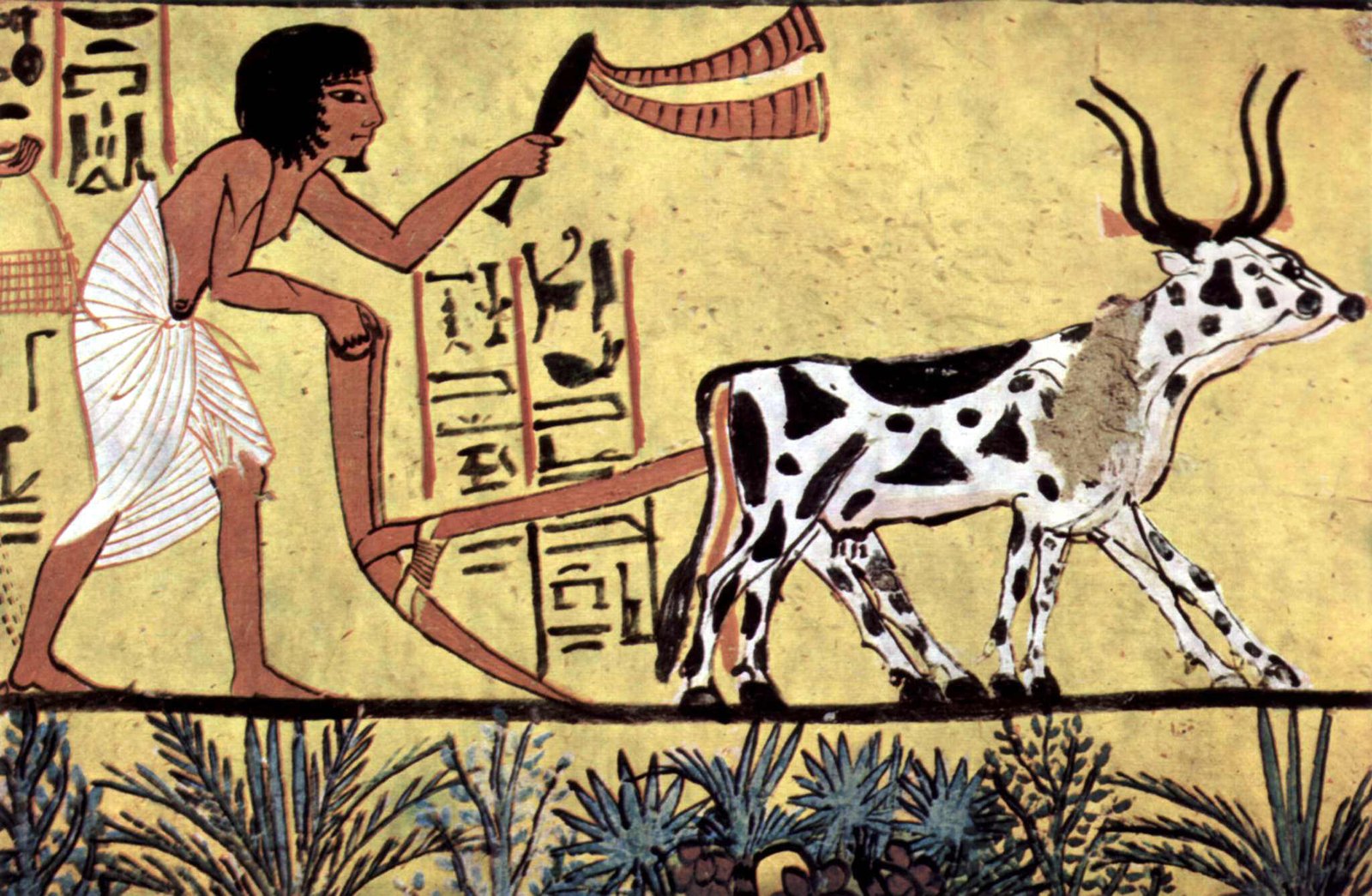

The story of the Ancestral Puebloans begins over 2,000 years ago, as early as 1200 BCE. These early peoples, originally hunter-gatherers, began to settle in the high deserts of the Southwest, slowly shifting toward a more sedentary lifestyle. They were among the first in North America to adopt agriculture, especially the cultivation of maize, which they likely inherited from contact with Mesoamerican cultures far to the south.

This gradual transformation from foraging to farming catalyzed a seismic shift. With agriculture came surplus, and with surplus came villages. The earliest Puebloan homes were simple pit houses dug into the ground, but by around 750 CE, above-ground structures made of adobe and stone began to appear, marking the beginnings of more permanent and sophisticated architecture.

Over the next few centuries, the Ancestral Puebloans evolved into brilliant builders, crafting vast complexes like those found in Chaco Canyon and Mesa Verde. These sites weren’t just villages; they were monumental hubs of culture, trade, and ceremony.

Chaco Canyon, located in modern-day New Mexico, became a cultural epicenter between 900 and 1150 CE. Multi-story “great houses” like Pueblo Bonito, with more than 600 rooms and aligned precisely with solar and lunar cycles, bear witness to the Ancestral Puebloans’ advanced astronomical knowledge and architectural genius. Roads fanned out from Chaco in all directions—straight, wide, and engineered with intent, suggesting a highly organized society with religious and political unity.

Meanwhile, on the steep cliffs of Mesa Verde in present-day Colorado, entire communities clung to rock faces in vertiginous stone villages like Cliff Palace and Spruce Tree House. These cliff dwellings, protected from weather and invaders, reflect a people who understood and adapted brilliantly to their environment.

A Culture Carved in Ceremonial Rhythm

To understand the Ancestral Puebloans is to appreciate the deep spiritual and communal rhythms of their lives. At the center of each community was the kiva—a circular, subterranean ceremonial chamber symbolizing the emergence of life from the underworld. Entered through ladders from above, kivas were sacred spaces where rituals, storytelling, and social gatherings took place. The presence of kivas in nearly every settlement underscores the deeply spiritual nature of Puebloan life.

Pottery, too, reveals a civilization rich in symbolism and connection. Black-on-white and red-on-orange ceramics bore intricate geometric patterns and often held spiritual significance. Their design changed over time and varied across regions, offering archaeologists clues about cultural influences and trade.

Perhaps most importantly, the Ancestral Puebloans weren’t isolated. They were part of a broader tapestry of Native cultures stretching into Mesoamerica. Turquoise, macaws, copper bells, and cacao—all non-native—have been found in Ancestral Puebloan sites, evidence of long-distance trade and exchange.

Signs of Strain: Drought, Depletion, and Division

Despite this golden age of architecture and community, signs of strain began to emerge. The environmental realities of life in the Southwest—arid climate, unpredictable rains, limited arable land—always demanded careful balance. But starting in the late 12th century, that balance tipped.

One of the most cited causes of the Puebloan decline is climate change, specifically the Great Drought, a prolonged dry period that began around 1275 and lasted nearly two decades. Tree-ring data confirms a significant reduction in rainfall during this period, affecting crops and water sources. For an agrarian society reliant on maize, this was catastrophic.

Agricultural output declined, and with it, food security. Malnutrition, especially among children, became more common. As people competed for dwindling resources, social tensions increased. Evidence from some sites suggests that the peaceful image of the Ancestral Puebloans may not tell the whole story. Fortified villages, signs of conflict, and even instances of cannibalism—a highly debated topic—suggest that survival sometimes took desperate forms.

Another factor was deforestation and overuse of natural resources. As populations grew, wood was harvested extensively for fuel and construction. Local ecosystems degraded, and carrying capacity diminished. The very success of the Puebloans may have inadvertently set the stage for their society’s unraveling.

Cultural fragmentation added to the stress. As central authorities like Chaco Canyon waned in power, smaller groups became more insular, and regional identities began to assert themselves. The unified system gave way to tribal diversity, and with diversity came disconnection.

The Great Migration: Disappearance or Dispersal?

By the end of the 13th century, the great cities of the Ancestral Puebloans—Chaco Canyon, Mesa Verde, Hovenweep—were largely abandoned. Homes were left intact, belongings left behind, kivas ritually closed. It wasn’t a haphazard flight; it appeared to be a planned, purposeful migration.

But where did they go?

Today, scholars believe the Ancestral Puebloans did not disappear, but dispersed. Many moved south and east, establishing new settlements in what are now the Rio Grande Valley of New Mexico and the Hopi Mesas of Arizona. Here, their descendants—modern Pueblo peoples such as the Hopi, Zuni, and Taos—continue to live, farm, and worship in ways that echo their ancestors’ traditions.

Archaeological evidence supports this migration theory. Pottery styles, architectural features, and oral traditions all show continuity between the Ancestral Puebloans and today’s Pueblo peoples. While the great stone cities of the canyons were left behind, the cultural heart of the Ancestral Puebloans lived on—adapted, transformed, but never extinguished.

The Legacy Lives On

For centuries, outsiders viewed the ruins of Chaco and Mesa Verde with mystery, sometimes even attributing them to “lost races” or foreign visitors. It wasn’t until Native voices and modern archaeology asserted the clear lineage that the truth became widely accepted: the descendants of the Ancestral Puebloans still live among us.

Today, Pueblo peoples maintain their languages, rituals, agricultural practices, and oral histories. Their dances still mark the seasons; their elders still tell the stories passed down for generations. Their values—community, harmony with nature, spiritual reverence—continue to guide their lives.

Meanwhile, the ruins they left behind are protected as national parks and UNESCO World Heritage Sites. Tourists from around the globe stand in awe before the towering walls of Cliff Palace or walk the silent roads of Chaco Canyon, marveling at a people who thrived in a land that tests the very limits of human endurance.

Reflections on Collapse and Continuity

The disappearance of the Ancestral Puebloans is not a tale of extinction. It is a story of resilience, adaptation, and transformation. It reminds us that civilizations do not always end in fire and ruin; sometimes, they simply move on.

Their exodus prompts important reflections for our modern age. As we face our own challenges of climate change, resource depletion, and social upheaval, the story of the Ancestral Puebloans becomes a cautionary tale—and a hopeful one. They left behind a legacy not of ruin, but of survival through change.

Their disappearance wasn’t the end of their story. It was the beginning of a new chapter, written by the hands of those who refused to vanish, who chose to move forward, and who continue to carry the ancient flame of their ancestors.