Around 1200 BCE, a thunderous storm swept across the Mediterranean world—not of nature, but of humanity. Cities burned, empires crumbled, and age-old traditions collapsed into smoke. This was the end of the Bronze Age, a time of monumental progress in art, trade, writing, and governance. But who—or what—triggered this downfall? In the ashes of once-thriving civilizations, a shadowy name appears again and again in the records of desperate kings and scribes: the Sea Peoples.

Neither empire nor kingdom, the Sea Peoples appear like phantoms in the historical record. They arrive suddenly and violently, only to vanish just as mysteriously. To this day, scholars argue over their identity, their origin, and their ultimate fate. Were they barbarian pirates? Climate refugees? Mercenaries turned on their masters? Or perhaps the first signs of a new world order?

This article explores the gripping mystery of the Sea Peoples—an enigma that not only reshaped the ancient world but continues to captivate historians and archaeologists alike.

The Bronze Age World Before the Storm

To understand the impact of the Sea Peoples, one must first appreciate the delicate web of civilizations they tore through.

By the 13th century BCE, the eastern Mediterranean was a vibrant hub of commerce, diplomacy, and culture. Egypt, under the New Kingdom, was a superpower stretching from the Sudan to Syria. The Hittites ruled Anatolia from their capital Hattusa. Mycenaean Greeks built palatial centers like Mycenae, Pylos, and Thebes, whose bureaucrats used an early form of Greek called Linear B. Ugarit, Byblos, and other coastal city-states thrived as trade intermediaries, importing tin and exporting luxury goods.

It was an interconnected world, arguably the first “globalized” economy in history. Bronze, the cornerstone of warfare and agriculture, required copper and tin—often imported from distant lands. Merchant ships plied the sea routes between Cyprus, Crete, and Egypt, carrying metals, textiles, wine, and grain. Letters inscribed on clay tablets reveal treaties and trade agreements, royal marriages, and appeals for aid among kings who called one another “brother.”

But this shimmering world was brittle. Its complexity was also its vulnerability. When disruptions came, they cascaded like dominoes—and into this fragile system, the Sea Peoples surged like a tsunami.

Enter the Sea Peoples: Flames in the Archive

The first chilling clues about the Sea Peoples come from the archives of kings under siege.

In Egypt, Pharaoh Ramesses III carved his victories into the walls of Medinet Habu, where we read of a coalition of strange, fearsome invaders:

“The foreign countries made a conspiracy in their islands. All at once the lands were removed and scattered in the fray. No land could stand before their arms, from Hatti, Kode, Carchemish, Arzawa, and Alashiya on, being cut off [destroyed] at one time.”

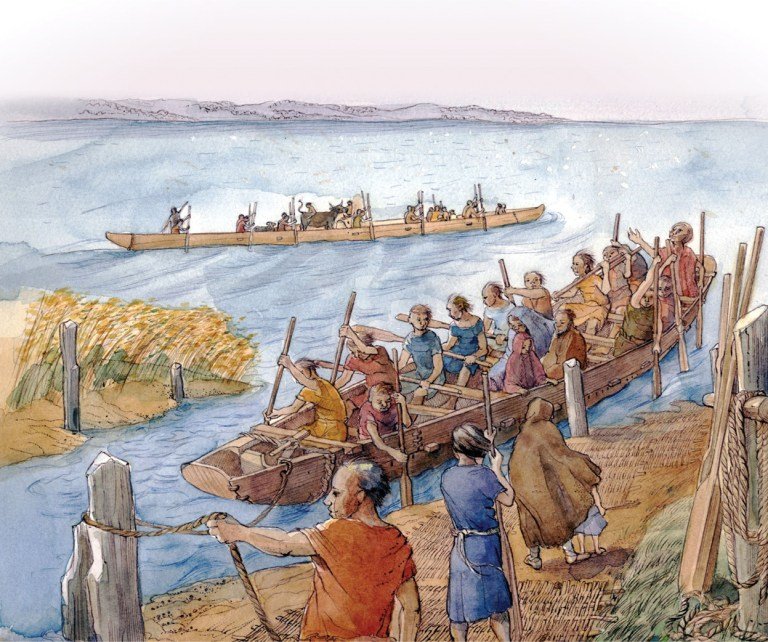

These invaders had names—Sherden, Shekelesh, Lukka, Peleset, Tjekker, Denyen, Weshesh—but no clear homeland. Ramesses III described their arrival by land and sea, with wagons and families in tow, suggesting they weren’t just raiders but migrating populations. Yet they came armed for conquest. Egyptian records describe pitched battles, including a famous naval engagement where Egyptian archers rained arrows down on invaders trying to breach the Nile Delta.

The records of other kingdoms tell similar tales. The Hittites vanish from history shortly after 1200 BCE. Ugarit’s final letters, unearthed centuries later, describe cities ablaze and fleets of enemy ships on the horizon. By the time scribes stopped writing, the Sea Peoples were not only invading—they were erasing.

The Identity Crisis: Who Were the Sea Peoples?

This is where the enigma deepens. The Sea Peoples left no chronicles, no city ruins attributed to them with certainty, no inscriptions boasting of victories. What we know comes from their victims—and those records are as cryptic as they are alarming.

Scholars have tried to match the named groups with known peoples, sometimes with tantalizing results:

- The Sherden may have come from Sardinia.

- The Shekelesh might link to Sicily.

- The Lukka are possibly the ancestors of the Lycians in southwest Anatolia.

- The Peleset are widely believed to be the Philistines, who later settled in Canaan.

- The Denyen may correspond to the Danaans of Greek myth, a term often used for Mycenaean Greeks.

- The Tjekker and Weshesh remain more obscure, though theories abound.

These identifications are speculative. Some scholars argue the Sea Peoples were not a single ethnicity but a patchwork of different groups—warriors, migrants, displaced peoples—united more by circumstance than origin. Like a medieval army of mercenaries, pirates, and vagabonds, they banded together for survival or plunder.

What we do know is that their arrival coincides with immense upheaval. If the Sea Peoples weren’t the cause of the collapse, they were its most visible symptom.

The Collapse of the Bronze Age: Coincidence or Consequence?

The Sea Peoples’ invasions coincided with one of the most dramatic societal breakdowns in human history: the Late Bronze Age Collapse.

Between 1200 and 1150 BCE, nearly every major city between Mycenae and Mesopotamia suffered destruction. The Hittite Empire disintegrated. Egyptian influence in Canaan faded. Mycenaean palaces were abandoned. Ugarit was never rebuilt. Trade networks collapsed, literacy declined, and urban populations shrank or vanished.

Why?

Scholars have proposed a storm of causes:

- Earthquakes ravaged the eastern Mediterranean, with geological evidence confirming seismic activity.

- Climate change and drought may have led to crop failures and famine.

- Internal rebellions and economic crises weakened the great powers from within.

- Technological shifts, including the rise of iron, may have made bronze-based powers obsolete.

- Migrations, possibly due to these other factors, created population pressures and conflict.

The Sea Peoples may have been both victims and aggressors—refugees fleeing collapse and warriors seizing opportunity. They may have destabilized kingdoms already reeling from other shocks, hastening their demise.

In this view, the Sea Peoples weren’t the spark—but they were certainly the fire.

The Philistines: A Glimpse Into Sea Peoples’ Legacy

Most groups linked to the Sea Peoples vanished into history, but one left a tangible footprint: the Peleset, believed to be the Philistines.

By the 12th century BCE, a new culture appears in the coastal cities of Canaan—Gaza, Ashkelon, Ashdod, Ekron, and Gath. These cities bear evidence of foreign influence: Aegean-style pottery, architecture, and dietary practices (like a fondness for pork, unusual in the region).

Biblical accounts describe the Philistines as formidable enemies of Israel, armed with advanced metallurgy and organization. Goliath, of David-and-Goliath fame, was a Philistine champion. Archaeology confirms that they were distinct from their neighbors—and likely descended from migrants who arrived by sea around 1200 BCE.

The Philistines offer a rare window into the Sea Peoples not as destroyers, but settlers. They adapted, assimilated, and endured—until the Babylonian conquest ended their story centuries later.

Modern Discoveries and Theories: Piecing Together the Puzzle

Archaeology continues to shed light on the Sea Peoples, though the puzzle remains incomplete.

Excavations at coastal sites like Dor and Ashkelon reveal destruction layers and sudden cultural shifts around 1200 BCE. Hattusa was abandoned. Ugarit’s final texts, discovered in the 20th century, contain urgent pleas for help—“The enemy ships are here!”—written mere days before the city was reduced to rubble.

Underwater archaeology, including shipwrecks like the Uluburun wreck off Turkey, reveals the immense scope of Bronze Age trade—and how fragile it was. When one link in the chain failed, the whole system crumbled.

In recent years, climate scientists have added another piece: sediment cores from the Mediterranean indicate a severe drought around 1200 BCE. If crops failed and food shortages followed, entire populations might have been forced to migrate—or fight.

Still, the Sea Peoples remain elusive. Some scholars even question whether they were ever a coherent group. Were they merely the name given to many different peoples fleeing or fighting for survival?

The Sea Peoples in Popular Culture and Imagination

Like the Atlantis myth or the Lost Tribes of Israel, the Sea Peoples have fired the imagination of storytellers and theorists.

They’ve appeared in historical novels, documentaries, and even speculative fiction. Some claim they were the Trojan War’s survivors. Others imagine them as early Vikings, or Atlanteans in disguise.

Less fancifully, they symbolize the chaos that follows when civilizations grow too complex, too interdependent, and too rigid. Their story resonates in our own age of climate stress, migration crises, and collapsing systems.

Indeed, the Sea Peoples are often invoked in modern debates about resilience and collapse. They remind us that no civilization—no matter how grand—is immune to disruption. And that history, far from linear, is often cyclical.

Conclusion: Raiders, Refugees, or Revolutionaries?

The Sea Peoples remain one of the great unsolved mysteries of antiquity. They appeared at the crossroads of war, migration, and environmental stress, and in their wake, the world changed forever.

Were they the barbarians at the gates? Perhaps. But they were also people—families, tribes, warriors—caught in a maelstrom not entirely of their own making. They were both destroyers and products of destruction. Their legacy lies not only in the cities they razed but in the new world that emerged from the ashes.

In the aftermath of the Sea Peoples’ invasions, the great empires of the Bronze Age gave way to smaller, more adaptable cultures. Out of this crucible emerged the Iron Age, and with it, the foundations of the modern Mediterranean world.

The Sea Peoples may have come from nowhere—but they helped shape everything that came after.