To the ancient Greeks, death was not an end but a passage—a crossing into a hidden realm that existed beneath the living world. This was the Underworld, the mysterious kingdom where the souls of mortals traveled once their earthly lives had ended. Unlike later visions of heaven and hell, the Greek Underworld was not simply a place of reward or punishment. It was a shadowy domain, shaped by myth, fear, and imagination, where the dead lingered as shades and where the living sometimes dared to venture.

The Underworld was not seen as a place of fire or eternal torment, nor as a paradise of light and peace. Instead, it was a mirror of human uncertainty about death: part solemn, part terrifying, part wondrous. In its depths lay rivers of forgetfulness and sorrow, gates guarded by monsters, and halls ruled by gods as stern as the fate they oversaw. To speak of the Greek Underworld is to speak of humanity’s oldest attempt to understand the greatest mystery of all—what happens after we die.

The Structure of the Underworld

The Greeks imagined the Underworld as vast and layered, a subterranean realm hidden deep beneath the earth. It was not uniform but divided into regions, each with its own purpose and population. The journey of a soul was thought to follow a path from the world of the living into the dominion of the dead, through rivers, gates, and judges who determined the soul’s fate.

At its center stood the palace of Hades, god of the Underworld, and his queen Persephone. Around them sprawled different regions: the Asphodel Meadows, where most souls wandered in forgetful shadows; the Elysian Fields, a place of beauty and reward; and Tartarus, a prison of torment reserved for the wicked and the enemies of the gods.

This geography was not rigid or uniform. Different poets and storytellers described it differently, adding new details or altering old ones. Yet the essence remained: the Underworld was a realm beneath the earth, divided by rivers, guarded by spirits, and ruled by inevitability.

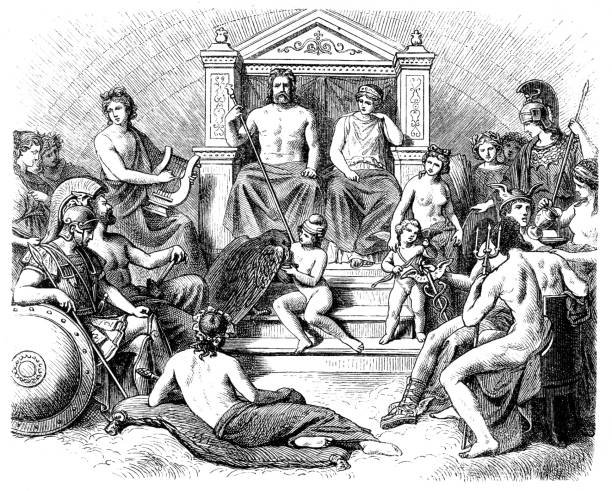

Hades: Lord of the Dead

The ruler of the Underworld was Hades, sometimes called Pluto by the Romans. Unlike his brothers Zeus and Poseidon, who commanded the sky and the sea, Hades presided over the hidden, silent kingdom of the dead. His name itself became synonymous with his realm, blurring the line between god and place.

Hades was not a devil figure. The Greeks did not see him as evil or malicious but as stern, inevitable, and impartial. His role was not to punish but to ensure that the order of life and death was maintained. He rarely left his dark kingdom, and when he did, myths often portrayed those journeys as moments of great consequence.

Though feared by mortals, Hades was not hated. He represented the unescapable truth of mortality. Unlike other gods who could be tricked or swayed, Hades was unyielding. Once a soul entered his realm, there was little chance of return.

Beside him stood Persephone, his queen, whose presence brought both fear and hope to the Underworld. Abducted from the earth, she became a goddess of both life and death, embodying the cycle of seasons and the eternal link between the living and the dead.

Persephone: The Queen of Both Worlds

The myth of Persephone is one of the most powerful in Greek mythology. She was the daughter of Demeter, goddess of the harvest, and her abduction by Hades became one of the defining tales of the Underworld. When Persephone was taken, Demeter’s grief caused the earth to wither, bringing famine to humankind. To restore balance, a compromise was struck: Persephone would spend part of the year with Hades in the Underworld and part with her mother in the world above.

This myth explained the cycle of the seasons—her return bringing spring and summer, her descent bringing autumn and winter. But beyond agriculture, Persephone became a figure of duality: she was both the maiden of flowers and the queen of shadows, both life-bringer and death’s consort.

Her presence gave the Underworld a deeper complexity. It was not only a place of endings but also of renewal. Persephone embodied the idea that death and life are bound together, inseparable, eternal.

The Five Rivers of the Dead

The journey into the Underworld was marked by rivers—natural boundaries between the world of the living and that of the dead. These rivers were more than physical features; they embodied the emotions and states of death itself.

The Styx, the most famous river, was sacred even to the gods. Its waters symbolized hatred and unbreakable oaths. To swear by the Styx was to bind oneself to a promise that could not be broken without dire consequences.

The Acheron was the river of sorrow or woe, across which souls were ferried into the realm of the dead. The ferryman Charon, grim and silent, carried souls across its waters—but only if they could pay him with a coin placed in their mouths at burial. Those without payment wandered the banks, restless and forlorn.

The Lethe, river of forgetfulness, offered oblivion. Souls who drank from it lost their memories of life, drifting into shadow without the burdens of their past. Philosophers later suggested that the Lethe might be linked to reincarnation, a cleansing before rebirth.

The Phlegethon, river of fire, burned with flames that did not consume. It flowed through the depths of Tartarus, symbolizing purification and eternal torment.

Finally, the Cocytus, river of lamentation, echoed with the cries of the unburied and forgotten, a river of tears that revealed the sorrow of neglected souls.

Together, these rivers painted the Underworld as a place of emotion and symbolism—hate, sorrow, forgetfulness, fire, and lamentation flowing eternally in its depths.

The Judges of Souls

Upon entering the Underworld, souls were thought to stand before judges who determined their fates. The most often named were Minos, Rhadamanthus, and Aeacus, once mortal kings who became judges after death.

Rhadamanthus judged the souls of Asia, Aeacus judged those of Europe, and Minos had the final say, settling disputes and making the ultimate decision. They were not gods but elevated mortals, chosen for their wisdom and fairness.

This judgment did not always mean punishment or reward. For many souls, the judgment simply determined whether they would wander the Asphodel Meadows or ascend to the Elysian Fields. For the wicked, however, Tartarus awaited.

The idea of judgment reflected a growing moral dimension in Greek thought: life’s deeds mattered, and death did not erase accountability.

The Asphodel Meadows: Realm of the Ordinary

The majority of souls did not experience torment or reward. Instead, they were believed to dwell in the Asphodel Meadows, a vast, shadowy plain where the dead wandered without passion or memory.

This realm was not cruel, but it was bleak. Souls here were shades—pale reflections of their former selves, stripped of desires and ambitions. It was a vision of death as quiet emptiness, a state neither blessed nor cursed.

The choice of asphodel flowers, which grew in Greek graveyards, as the symbol of this realm is telling. The plant was hardy, simple, and enduring—just as the Meadows represented the common fate of ordinary mortals.

The Asphodel Meadows remind us that in Greek thought, immortality and glory were rare. For most, death was simply a continuation of existence in muted shadow.

The Elysian Fields: Isles of the Blessed

For a select few, death led to the Elysian Fields, also called the Isles of the Blessed. This was the Greek vision of paradise, a realm of eternal springtime, gentle breezes, and endless joy. Here, the heroic and the virtuous dwelled after death, free from suffering and sorrow.

The Elysian Fields were not reserved for the wealthy or powerful but for those favored by the gods or remembered for their virtue. Heroes like Achilles or Orpheus were imagined to wander here, enjoying an afterlife of peace and honor.

Later traditions expanded the idea, imagining cycles of reincarnation where souls could achieve Elysium after living three virtuous lives. In this way, Elysium became not only a paradise but a reward for wisdom, courage, and justice.

The Fields reveal the Greeks’ yearning for hope beyond death, a dream of beauty and rest in contrast to the shadows of the Meadows.

Tartarus: The Pit of Torment

If Elysium was paradise, then Tartarus was the abyss. Far below even the Underworld, Tartarus was a place of punishment for the wicked, the impious, and the enemies of the gods. It was both prison and pit, surrounded by walls of bronze and gates of iron.

Here, the Titans who once battled Zeus were chained in eternal darkness. Here, figures like Sisyphus, condemned to roll his boulder forever, and Tantalus, eternally thirsty and hungry, suffered punishments that matched their crimes.

Unlike later concepts of hell, Tartarus was not for all sinners but for those whose crimes offended the gods or disrupted the order of the cosmos. It was divine justice in its most terrifying form, a place of endless punishment that reinforced the power of Olympus.

The horrors of Tartarus were vivid reminders to mortals that defiance of divine order had eternal consequences.

Guardians of the Underworld

The Underworld was not unguarded. At its gates stood Cerberus, the monstrous three-headed dog, loyal to Hades and fierce in his duty. His task was not to keep souls out but to keep them in—ensuring that once the dead entered, they did not escape.

Other guardians included the Furies (Erinyes), avenging spirits who pursued wrongdoers even into death. The Hecatoncheires, hundred-handed giants, were said to guard Tartarus itself. Even the rivers served as barriers, preventing escape or intrusion.

These guardians made the Underworld a fortress as much as a kingdom, emphasizing that death was final and that the boundaries between life and death could rarely be crossed.

Mortal Journeys into the Underworld

Despite its fearsome barriers, myths tell of mortals and even gods who dared to descend into the Underworld. Heroes such as Orpheus, who sought to bring back his beloved Eurydice, or Heracles, who captured Cerberus as one of his labors, became legendary for their journeys into death’s realm.

These stories reveal both the terror and fascination the Greeks felt toward the Underworld. Such journeys were not only physical descents but also symbolic ones—encounters with mortality, courage, and the limits of human power.

Even Odysseus, in Homer’s Odyssey, visited the land of the dead, seeking wisdom from the prophet Tiresias. His journey portrayed the Underworld as a place of knowledge, where the shades of the past held secrets for the living.

These myths reflected the universal human longing: to understand, to conquer, or to escape death.

The Underworld in Greek Religion and Culture

The belief in the Underworld was not merely myth but an integral part of Greek religion and daily life. Funerary rituals—burial, offerings, and libations—were essential to ensure that the soul could pass peacefully into Hades’ realm. To neglect these rites was to condemn a soul to wander restlessly, cut off from both worlds.

Mystery cults, such as those of Orpheus and Eleusis, promised initiates secret knowledge of the afterlife and the hope of a better fate beyond death. These cults reveal how deeply the Underworld shaped Greek spirituality, offering not only fear but also the possibility of hope.

Even philosophy engaged with the Underworld. Plato used myths of judgment and reincarnation to explore ethics, justice, and the immortality of the soul. The Underworld was not just a mythic place—it was a canvas upon which Greeks projected their deepest questions about morality, destiny, and existence.

The Psychological Landscape of the Underworld

Beneath its geography and myths, the Greek Underworld is also a psychological map of human attitudes toward death. The rivers reflect emotions—hatred, sorrow, forgetfulness, lamentation—while the regions embody the possibilities of mortality: emptiness, reward, or punishment.

In this way, the Underworld is less a physical place than a mirror of the human soul. It expresses the fear of oblivion, the desire for justice, the hope for paradise, and the dread of eternal punishment. To enter its myths is to explore the depths of the human psyche, where mortality shapes meaning.

The Legacy of the Greek Underworld

Though centuries have passed since the Greeks worshiped their gods, the imagery of the Underworld endures. From Dante’s Inferno to modern films and novels, the idea of a shadowy realm of the dead continues to inspire. Cerberus guards video games as fiercely as he once did myth. Rivers like Styx and Lethe still flow through poetry and literature.

The Greek Underworld shaped Western ideas of the afterlife, justice, and the soul. Even when reinterpreted by later religions and philosophies, its core ideas remain: that death is a journey, that the soul persists, and that what we do in life echoes beyond the grave.

Death, Mystery, and Meaning

The Greek Underworld was never just a place of fear. It was a place of mystery, reflection, and meaning. For the Greeks, to imagine death was also to imagine life—its fragility, its value, and its purpose.

In Hades’ silent halls, in Persephone’s dual role as maiden and queen, in the rivers that carried sorrow and oblivion, the Greeks expressed both terror and wisdom. The Underworld taught them that mortality is inescapable, but it also invited them to live with courage, virtue, and remembrance.

To speak of the Greek Underworld is to step into humanity’s oldest meditation on mortality. It is a realm not of demons but of shadows, not of flames but of memories, not of despair but of eternal questions.

And in its depths, we see reflected our own unending search to understand what lies beyond the veil of death.