In the ancient world, death was not seen as an ending but as a passage. For the Greeks, to cross from life into death was to enter another realm entirely, where shadows walked in fields of dusk, and the souls of the departed awaited their fate. Yet the afterlife was not an ungoverned place. It had order, hierarchy, and judgment. The Greeks envisioned a system where even the dead could not escape justice, and at the heart of this vision stood three legendary figures: Rhadamanthus, Aeacus, and Minos, the Judges of the Dead.

These three were not arbitrary figures but kings elevated by their virtue, wisdom, and sense of fairness. After ruling in life, they became the arbiters of souls in death. They weighed the deeds of mortals, decided their destinies, and ensured that the underworld remained a realm not of chaos but of balance. In their court, the greatness and folly of human life found their ultimate reckoning.

Their stories weave together themes of justice, myth, morality, and the timeless question of what it means to live a good life. To study them is to step into the Greek vision of cosmic order—where law and morality extend beyond the grave itself.

The Underworld and Its Mysteries

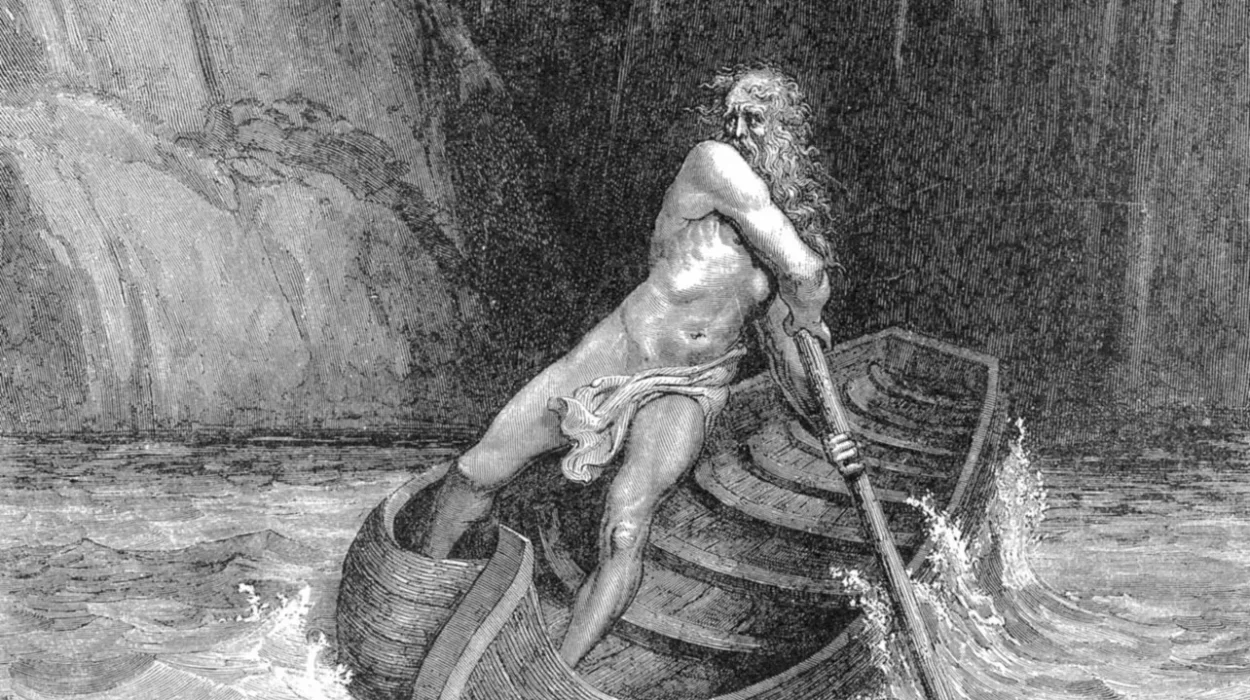

Before we enter the court of the judges, it is essential to understand the stage upon which they preside: the Greek underworld. Governed by Hades, the god of the dead, the underworld was not a place of fiery torment as later cultures imagined. It was instead a vast, shadowy domain beneath the earth, divided into different regions where souls were sent depending on their lives.

The ordinary dead wandered in the Asphodel Meadows, a neutral place where existence was a pale reflection of earthly life. Heroes and the exceptionally virtuous might ascend to the Elysian Fields, a paradise of eternal joy. The wicked, however, were cast into Tartarus, a place of punishment and suffering as dark as it was eternal.

But how did a soul know where it belonged? This is where Rhadamanthus, Aeacus, and Minos entered the myth. They were the judges, the arbiters of human morality, deciding whether a soul would walk in peace, glory, or torment. Their role gave the underworld structure, echoing the Greek belief that justice was not bound to mortal courts but extended into eternity.

Rhadamanthus: The Judge of the Righteous

Among the three, Rhadamanthus was renowned as the embodiment of justice and incorruptibility. A son of Zeus and Europa, and the brother of Minos, he was famed for his fairness long before his death.

In life, Rhadamanthus ruled the Cretan islands and was so respected for his wisdom and laws that later thinkers claimed his decrees inspired the laws of Sparta. His reputation was such that he became a symbol of incorruptible justice. Even Homer refers to the “Elysian plain where Rhadamanthus dwells,” associating him directly with the blessed afterlife.

In the underworld, Rhadamanthus was said to preside over the judgment of souls from Asia. His task was not simply to punish but to reward, to guide those who had lived virtuous lives toward the Elysian Fields. His name became synonymous with righteousness itself, a figure who embodied the ideal that justice should be impartial, swift, and fair.

To be judged by Rhadamanthus was to be weighed against a standard of virtue untarnished by favoritism or corruption. In him, the Greeks placed their highest ideals of law and morality.

Aeacus: The Guardian of the Gates

If Rhadamanthus represented incorruptible justice, Aeacus embodied piety and the role of a faithful guardian. Like his fellow judges, Aeacus was a son of Zeus, born to the mortal woman Aegina. Known for his fairness and devotion to the gods, he was beloved by both mortals and immortals.

In life, Aeacus ruled the island of Aegina. When a devastating plague struck his people, he prayed fervently to Zeus for deliverance. His prayers were answered in a strange and powerful way: Zeus transformed ants into humans, creating a new race of people known as the Myrmidons. This act linked Aeacus forever to themes of survival, renewal, and divine favor.

Because of his extraordinary devotion, Aeacus was made a judge in the afterlife, often depicted as the one who oversaw the keys of Hades and the gates of the underworld. While Rhadamanthus judged souls from Asia, Aeacus judged those from Europe, dividing humanity geographically in their eternal trial.

His role as gatekeeper reinforced the idea of balance and vigilance. Justice was not only about deciding reward or punishment but also about safeguarding the order of the afterlife itself. Aeacus symbolized loyalty to divine will, a reminder that human morality was inseparable from reverence for the gods.

Minos: The King of Final Authority

Of the three judges, Minos was the most complex and formidable. Also a son of Zeus and Europa, Minos was the king of Crete, remembered both as a great ruler and a figure of controversy. In myth, he was the one who demanded the sacrifice of Athenian youths to feed the Minotaur in the Labyrinth, a deed that cast him in a darker light than his brother Rhadamanthus.

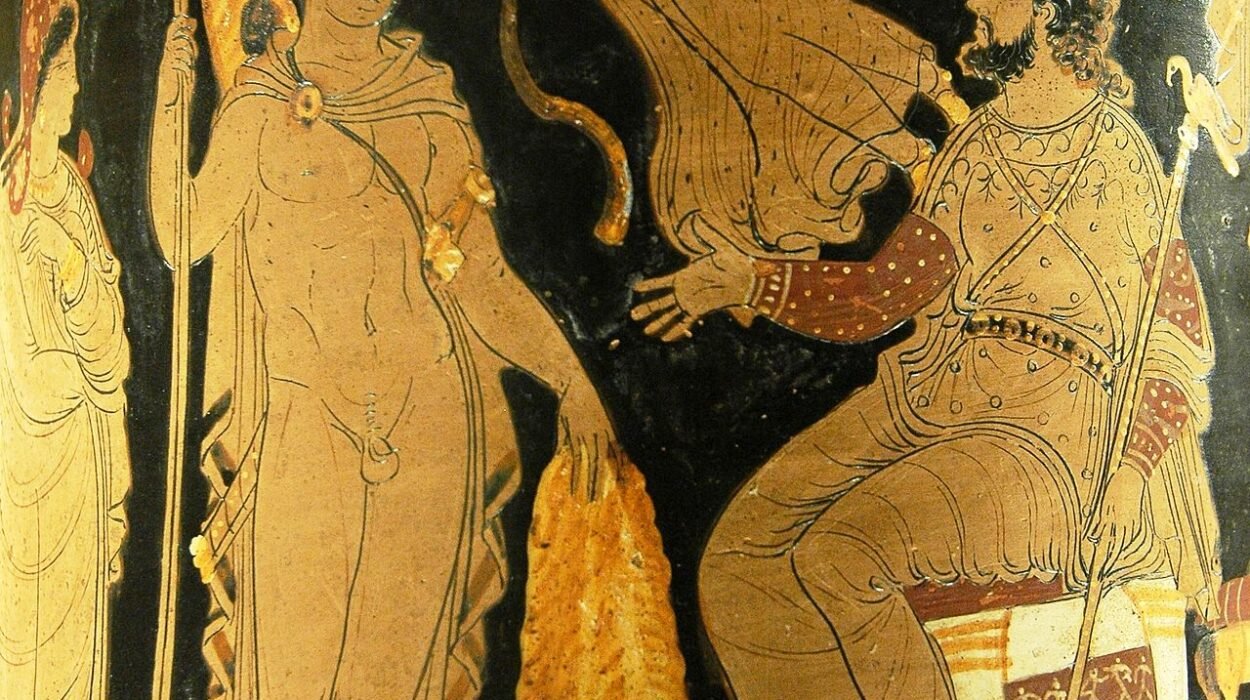

Yet it was Minos who was ultimately given the role of supreme judge in the underworld. While Rhadamanthus and Aeacus each judged their assigned souls, Minos served as the arbiter of appeals, the one whose word was final. His authority was absolute, a reflection of his kingship in life.

In Homer’s Odyssey, Odysseus encounters Minos in the underworld, described as seated on a throne with a golden scepter, passing judgment over the dead. His presence in this scene reinforces his role as the ruler of justice beyond death, an eternal king whose authority transcended mortality.

Minos symbolizes the complex relationship between justice and power. Unlike his brother Rhadamanthus, who is remembered only for fairness, Minos represents the fusion of rulership and judgment. He is not merely a dispenser of law but a sovereign whose decisions carry the weight of command.

Justice Beyond the Grave

The presence of Rhadamanthus, Aeacus, and Minos in Greek mythology reveals how deeply the ancient Greeks valued the concept of justice. In a world where human life was fleeting and often unpredictable, the assurance that one’s deeds would be weighed after death offered both comfort and warning.

For the virtuous, the judges promised eternal reward in the Elysian Fields, a paradise where heroes and the righteous lived in bliss. For the wicked, they guaranteed punishment in Tartarus, a realm of darkness where even kings and tyrants could not escape the consequences of their cruelty.

This vision of posthumous judgment reflected the Greek conviction that morality was universal and enduring. Justice was not merely the law of kings or courts but a cosmic principle that outlasted life itself.

The Symbolism of the Three Judges

The triad of Rhadamanthus, Aeacus, and Minos carries symbolic weight beyond their individual stories. Together, they represent different dimensions of justice:

- Rhadamanthus as incorruptible fairness and the reward of virtue.

- Aeacus as faithful devotion, guardianship, and vigilance.

- Minos as sovereign authority, the final arbiter whose command shaped destiny.

In uniting these figures, Greek myth suggested that justice was not simple but layered. It required fairness, piety, and authority in harmony. To live well was not only to act justly but also to honor the gods and respect rightful authority.

Echoes in Later Thought

The Judges of the Dead did not fade with Greek mythology. Their presence echoed throughout Roman culture, literature, and even into later philosophical and religious traditions. Virgil’s Aeneid speaks of Minos judging the dead, while Aeacus appears in Roman writings as a model of integrity.

In later centuries, the image of judges of the dead resonated with Christian visions of the afterlife, where souls are weighed and judged. Though the names changed, the idea endured: death is not the end, but the threshold of judgment.

The endurance of these myths reveals how deeply humans long for justice that transcends human imperfection. In every culture, the idea persists that the soul must one day answer for its deeds.

The Human Need for Judgment

Why did the Greeks imagine such figures? Why not let death be silence, or the afterlife a place of shadows without consequence? The answer lies in the human need for meaning.

Life, with its chaos, injustice, and fleeting joys, often feels unbalanced. The innocent suffer, the guilty thrive, and justice in the mortal world is often flawed. By envisioning judges in the afterlife, the Greeks created a cosmic balance, a reassurance that no deed would go unanswered.

The figures of Rhadamanthus, Aeacus, and Minos remind us that human beings crave accountability. Whether in this life or the next, we long to believe that justice is real, that morality matters, and that there is a deeper order to existence.

A Legacy Carved in Eternity

Today, the Judges of the Dead remain powerful symbols not just of mythology but of human ideals. They represent the yearning for fairness, the recognition of authority, and the need to honor higher laws. Their stories, passed down through Homer, Hesiod, Plato, and countless later writers, endure because they speak to the timeless human struggle to define justice.

To imagine them seated in the halls of Hades is to glimpse the Greek soul: wise, questioning, reverent, and ever aware that life’s deeds ripple into eternity.

In Rhadamanthus, Aeacus, and Minos, we find more than judges of the dead—we find reflections of humanity’s search for meaning, morality, and truth beyond the grave. They stand as eternal reminders that to live is not only to breathe and act but to prepare for the final court where all actions are weighed.

And perhaps this is the ultimate gift of their myth: not fear of judgment, but inspiration to live with justice, devotion, and honor, knowing that life’s story does not end with death, but continues in the eternal balance of the cosmos.