Long before written language shaped civilizations, humans sat beneath open skies and beside flickering fires, telling stories. These stories weren’t merely entertainment—they were explanations, warnings, memories, and dreams. They told of gods hurling lightning, serpents coiled beneath the earth, great floods, cosmic eggs, and trees that touched the heavens. From the Aboriginal Dreamtime to the Greek pantheon, from Norse sagas to the epics of India, mythology has remained a mirror to the human soul.

But what are myths, really? Are they ancient truths passed down in symbolic form? Are they poetic metaphors to explain the inexplicable? Or are they collective memories—fragments of real events distorted by time and imagination?

This question has haunted philosophers, historians, archaeologists, and psychologists alike. To understand the origin of myths is to understand the origin of the human imagination. And that journey takes us deep into the oldest layers of civilization—and perhaps even beyond recorded history.

The Myth as Metaphor: Ancient Psychology in Disguise

One of the most enduring theories about the origin of myths is that they are metaphors—beautiful, symbolic stories that convey truths too complex or abstract to be stated plainly. Just as a poem uses imagery to express emotion, myths use gods, monsters, and epic quests to explore the mysteries of existence.

The psychoanalytic tradition, led by figures like Sigmund Freud and Carl Jung, saw myths as expressions of the human subconscious. For Freud, myths were collective expressions of repressed desires and fears. The Oedipus myth, he argued, wasn’t just a tale of patricide and incest—it was a mirror of universal psychological conflicts. Jung took this further, suggesting that myths were manifestations of “archetypes”—innate, universal patterns that exist within the collective unconscious of humanity.

Under this lens, the dragon becomes not just a fire-breathing beast, but a symbol of inner demons. The hero’s journey isn’t merely a narrative arc—it’s the symbolic path of self-discovery. Myths become metaphors for human psychology, morality, and identity.

This metaphorical view explains why similar myths arise independently in distant cultures. The archetypes are shared because the human mind is shared. We all fear death, yearn for love, and seek meaning. Myth, then, is the language of the soul, expressed through the grammar of gods.

The Myth as Memory: Echoes of a Forgotten Past

Yet myths may also carry something older and more literal—fragments of real events, catastrophes, or migrations preserved through oral tradition.

Consider the myth of a great flood, found in cultures from Mesopotamia to Mesoamerica, from China to Australia. Is it coincidence, or memory? Geological evidence shows that the end of the last Ice Age saw massive flooding events—glacial lakes bursting, sea levels rising, coastlines drowning. Could these have left such an impression on early humans that they were preserved as stories of divine judgment and watery apocalypse?

The destruction of Atlantis, described by Plato as a once-great island that sank beneath the sea, has long fascinated scholars and dreamers. While some see it as a moral allegory, others believe it may be a memory of a real sunken landmass or advanced culture lost to catastrophe—perhaps the Minoans of Thera, devastated by volcanic eruption.

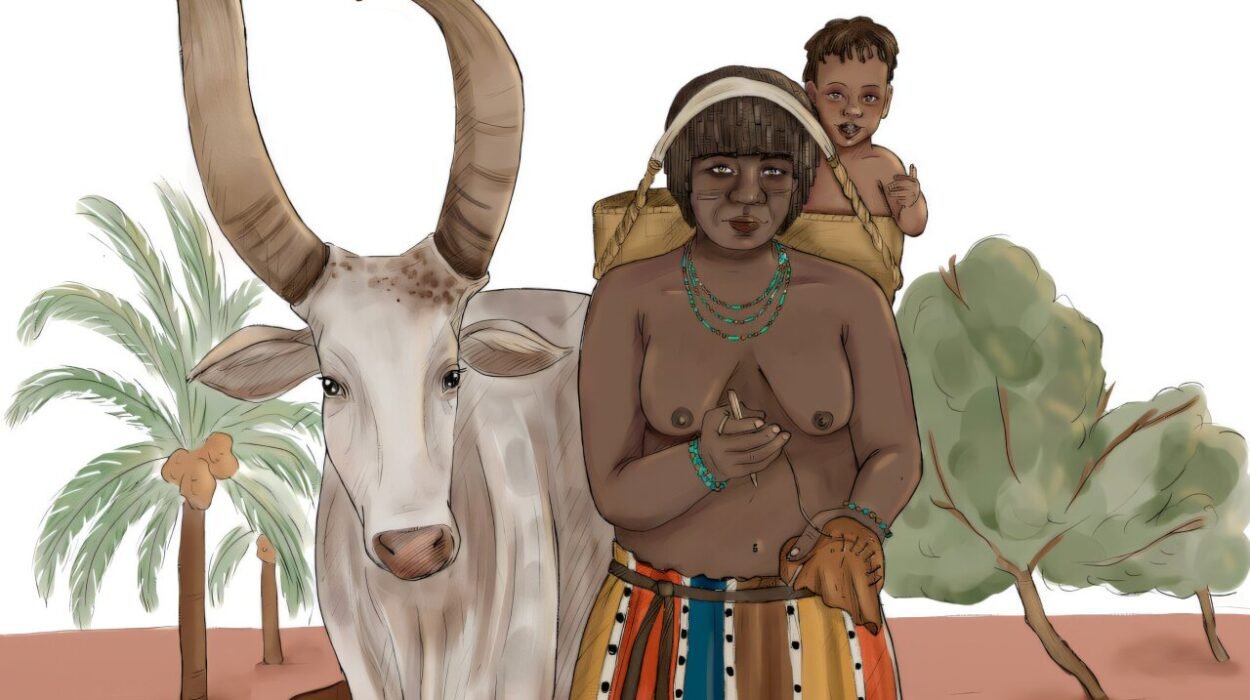

There are other tantalizing examples. The Maori of New Zealand speak of ancestral migrations from a sunken homeland called Hawaiki. The Dogon of Mali tell of star systems and cosmology that some argue they couldn’t have known without ancient contact. Aboriginal myths describe landscapes that match Ice Age geography.

In these myths, memory hides beneath metaphor. They are like old photographs blurred by the years, their subjects barely visible, but still recognizable if we look closely enough.

The Myth as Truth: Cosmologies and the Quest for Meaning

Many ancient peoples would not have seen their myths as metaphors or memories. They would have considered them truths—sacred, divine revelations that explain the origin of the world and humanity’s place in it.

The Rigveda of ancient India, composed over 3,000 years ago, speaks of a primordial being whose sacrifice created the cosmos. The ancient Egyptians believed in a sun god who sailed a celestial barque across the sky, fighting the serpent of chaos each night to ensure the dawn. For the Norse, the world was born from the body of a slain giant, and its fate is to end in a fiery battle called Ragnarök.

To dismiss these myths as mere stories is to misunderstand them. For their creators, they were cosmologies—explanations of why the world exists, what laws govern it, and how humans should live within it. Myth and religion were intertwined, and truth was not limited to material facts. Mythical truth operated on a different level: symbolic, spiritual, existential.

This kind of truth still resonates today. Many people continue to find meaning in the parables of the Bible, the lessons of the Bhagavad Gita, or the teachings of the Quran. These stories are not validated by archaeology, but by their ability to move hearts and shape cultures. They are mythic truths, passed from generation to generation, enduring through faith and ritual.

The Myth as Social Code: Constructing Civilization

Myths do more than explain the cosmos—they define the rules of society. They justify hierarchies, sanction laws, and encode moral values. In this sense, myths are the DNA of culture.

The Code of Hammurabi, one of the oldest legal documents in the world, begins with a mythic preamble: the gods chose Hammurabi to rule and bring justice. Similarly, the divine right of kings in medieval Europe drew from Christian mythos to legitimize power. The myths of Rome—Romulus and Remus, descended from Mars—provided sacred origins for empire.

In tribal societies, myths often define the roles of men and women, the boundaries between clans, the taboos that must not be broken. The mythic ancestors of the Australian Aboriginal Dreamtime created the land, named its creatures, and established laws that still govern behavior.

Even modern societies are not immune. Nations craft founding myths to bind people together. The American Revolution is remembered not just as a historical event, but as a mythic struggle for liberty. The French Revolution gave birth to the myth of universal rights. Political ideologies, from capitalism to communism, are built upon narrative myths—stories of progress, struggle, and destiny.

In this way, myth is not just ancient—it is always present, shaping how we think, how we belong, and how we act.

Common Threads: The Shared Myths of Humanity

One of the most fascinating aspects of mythology is the recurrence of similar themes across cultures that had no apparent contact. Why do so many cultures speak of a great flood? Why do so many mythologies feature a trickster figure, a dying god, a sacred tree, or a hero who journeys to the underworld?

These shared motifs may point to universal psychological patterns, as Jung believed. Or they may be remnants of a common ancestral mythology, carried by migrating humans across the globe. The field of comparative mythology, pioneered by scholars like Joseph Campbell, explores these parallels to uncover a “monomyth”—a single, archetypal narrative structure behind the myths of the world.

The hero’s journey, for example, appears in stories from Gilgamesh to Hercules to Luke Skywalker. It begins with a call to adventure, leads through trials and revelations, and ends in transformation and return. This pattern, Campbell argued, reflects the structure of human growth itself.

The serpent is another recurring symbol. Sometimes it is evil, as in Genesis. Sometimes wise, as in Mesoamerican and Hindu mythology. Sometimes it guards treasure, sometimes it brings death and rebirth. It slithers through the human subconscious like a hidden riddle.

These shared symbols suggest that myths are not arbitrary. They arise from deep currents within the human mind and shared experiences across cultures. They connect us, even when we speak different languages and worship different gods.

Lost Myths: Voices from the Silent Past

For every myth that survives, countless others have been lost. Oral traditions fade, temples are buried, languages die. The myths of the Etruscans, the Scythians, the Indus Valley peoples—these are whispers in the dust, known only through fragments or speculation.

Sometimes, we rediscover these lost myths through archaeology. Clay tablets unearthed in Mesopotamia revealed the Epic of Gilgamesh, a story lost for over two millennia. The deciphering of Egyptian and Mayan hieroglyphs opened doors to forgotten pantheons and cosmic battles.

Yet many myths remain locked in silence. The Linear A script of the Minoans has never been deciphered. The pre-Incan myths of the Andes are only partially reconstructed from colonial records. Entire mythologies may be buried under our feet, waiting for a trowel or a spark of insight to awaken them.

This sense of loss adds a poignancy to the study of myth. We are heirs to a fragmented inheritance—scraps of wisdom from ancient minds, echoing across time.

Myth in the Modern World: Echoes in the Age of Science

In the modern world, myth has not vanished. It has evolved.

Science fiction and fantasy, far from being escapist entertainment, are often the new myths of our time. They grapple with identity, morality, technology, and the future. Characters like Superman, Neo, and Frodo Baggins fulfill archetypal roles. Worlds like Star Wars, Harry Potter, and the Marvel Universe function as shared mythologies for global audiences.

Even science itself sometimes adopts mythic language. The Big Bang, black holes, the multiverse—these are awe-inspiring concepts that border on the mythic in their scale and mystery. Science may not require gods, but it still seeks answers to the same cosmic questions: Where did we come from? Why are we here? What is our destiny?

Myth also survives in ritual, symbol, and art. Weddings, funerals, national anthems, and sporting events all carry mythic weight. They reaffirm our values, our identities, and our connection to something larger than ourselves.

In an age of algorithms and automation, the myth remains a human heartbeat. It reminds us that logic is not the only path to truth—and that imagination is a force as ancient as fire.

Conclusion: Myth as the Soul’s Compass

So what, in the end, is a myth? Is it truth, metaphor, or memory?

Perhaps it is all three—and more. A myth is a vessel, a mirror, a map. It holds fragments of forgotten cataclysms, encoded in the language of gods. It speaks in riddles, but its meaning is clear to those who listen with heart as well as mind. It comforts the dying, inspires the living, and guides the seeker through the dark.

In a world driven by data and dominated by facts, myths remind us that not all truths can be measured. Some must be dreamed, sung, and remembered.

And perhaps, in every myth we tell, we are not just recalling the past—we are shaping the future.