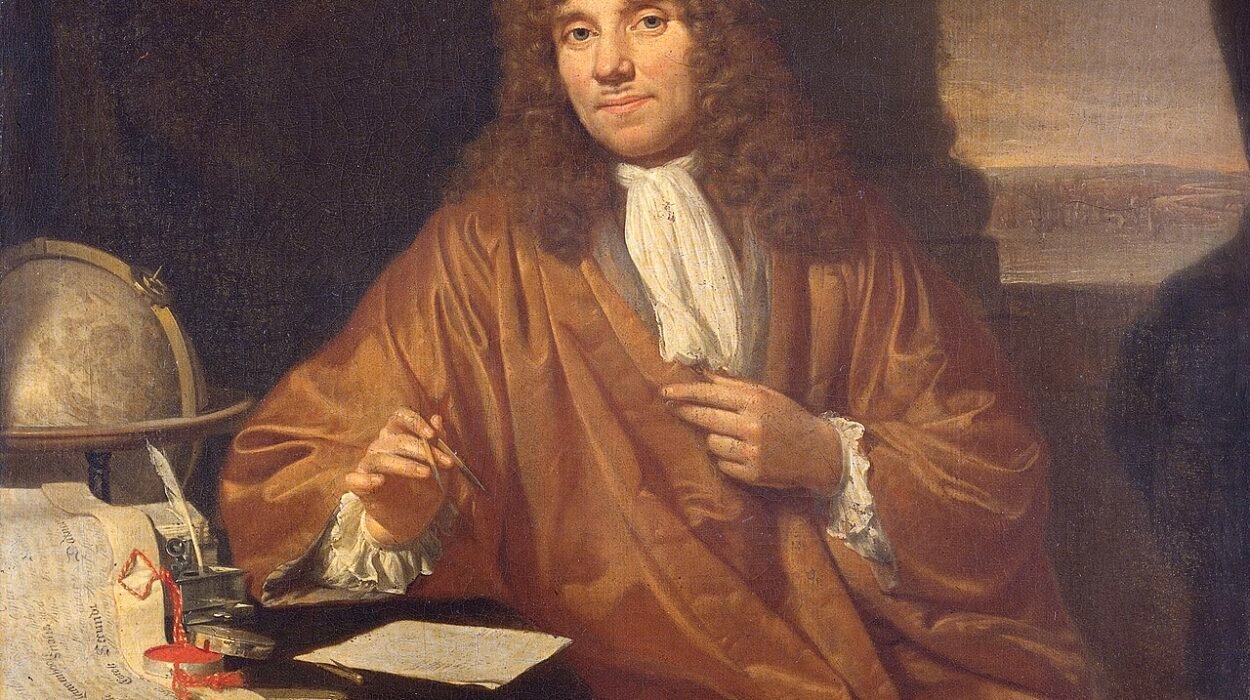

William Harvey (1578–1657) was an English physician whose groundbreaking work fundamentally transformed the understanding of the circulatory system. Born in Folkestone, England, Harvey studied medicine at the University of Padua, where he was exposed to advanced anatomical research. His most notable contribution, detailed in his 1628 work De Motu Cordis (On the Motion of the Heart and Blood), was the first comprehensive description of the heart’s role in pumping blood through a closed circulatory system. Harvey’s discovery that blood circulates continuously through the body, driven by the heart, challenged the prevailing Galenic theories of the time. This revolutionary insight laid the foundation for modern physiology and significantly advanced the field of medicine. Harvey’s meticulous research and experimental approach earned him a lasting legacy as one of the pioneers of modern medical science.

Early Life and Education (1578-1602)

William Harvey was born on April 1, 1578, in Folkestone, Kent, a picturesque coastal town in southeastern England. His father, Thomas Harvey, was a prosperous yeoman and businessman, known for his work as a farmer and merchant. William’s mother, Joan Halke, hailed from a well-regarded family with strong ecclesiastical ties, giving young William a blend of both mercantile and clerical influences during his formative years.

As the eldest of nine children, William Harvey was likely expected to set an example for his younger siblings. From a young age, he exhibited an insatiable curiosity about the natural world, a trait that his parents nurtured. They recognized his academic potential and ensured that he received a solid education, which was somewhat uncommon for children of his social standing during the late 16th century.

In 1588, at the age of 10, Harvey was sent to The King’s School in Canterbury, a prestigious institution that had been educating boys since the early medieval period. The curriculum at The King’s School focused heavily on the classical education that was typical of the Renaissance period, emphasizing Latin, Greek, rhetoric, and philosophy. These subjects were considered essential for a young man who would later pursue a professional career in law, the church, or medicine. Harvey excelled in his studies, demonstrating a particular aptitude for languages and logical reasoning, both of which would serve him well in his later medical career.

The intellectual climate of England during Harvey’s youth was one of both tradition and transformation. The country was in the midst of the Elizabethan era, a time of great cultural flourishing. The works of Shakespeare, the exploration of new lands, and the clash of religious ideas all contributed to an environment where questioning old assumptions and seeking new knowledge was increasingly encouraged. However, the medical practices of the time were still heavily influenced by the works of ancient authorities like Galen and Aristotle, whose teachings had gone largely unchallenged for over a millennium.

In 1593, at the age of 15, Harvey matriculated at Gonville and Caius College, Cambridge. His admission to this prestigious university marked a significant step in his academic journey. At Cambridge, he continued his classical studies while also being introduced to the natural sciences. The college, founded in 1348, had a long tradition of producing scholars who would go on to make significant contributions to various fields, and it provided Harvey with a rigorous academic environment.

While at Cambridge, Harvey was exposed to the works of contemporary thinkers and scientists who were beginning to challenge the dogmas of the past. The university’s curriculum was increasingly influenced by the ideas of the Renaissance, a cultural movement that emphasized the rediscovery of classical knowledge and the application of empirical observation to understand the natural world. This period in Harvey’s life was crucial, as it laid the foundation for his later rejection of traditional medical doctrines in favor of a more experimental and observational approach.

After completing his Bachelor of Arts degree in 1597, Harvey faced a crucial decision about the direction of his future career. Although he had a strong interest in the natural sciences, it was medicine that ultimately captured his imagination. The desire to understand the inner workings of the human body, combined with a sense of duty to help others, led him to pursue a medical career. In 1599, seeking the best education available, Harvey enrolled at the University of Padua in Italy, a decision that would profoundly influence the course of his life.

The University of Padua was one of Europe’s leading centers for medical education. It was renowned for its progressive approach to teaching, which emphasized hands-on dissection and the direct observation of anatomical structures. Padua was also a hub of intellectual exchange, attracting students and scholars from across Europe who were eager to study with its esteemed faculty. Harvey’s time in Padua, particularly under the mentorship of the great anatomist Girolamo Fabricius, was instrumental in shaping his scientific approach and his eventual discoveries about the circulatory system.

Early Career and the Pursuit of Knowledge (1602-1628)

Upon completing his studies at the University of Padua in 1602, William Harvey returned to England, equipped with a Doctor of Medicine degree and a new, more empirical approach to the study of the human body. His education at Padua had not only provided him with advanced knowledge of anatomy and physiology but had also instilled in him a deep respect for the scientific method, which emphasized observation, experimentation, and the questioning of established ideas.

Harvey began his medical practice in London, a city that was rapidly growing in size and importance. London in the early 17th century was a bustling metropolis, with a population approaching 200,000 people. It was a city of contrasts, where wealth and poverty, tradition and innovation, existed side by side. The medical profession was still largely unregulated, and physicians often competed with barber-surgeons, apothecaries, and folk healers for patients. Despite these challenges, Harvey quickly established himself as a capable and compassionate physician.

In 1604, just two years after his return to England, Harvey was admitted as a fellow of the Royal College of Physicians. This prestigious institution, founded in 1518, played a crucial role in the professionalization of medicine in England. As a member of the College, Harvey gained access to a network of influential colleagues, as well as to the latest medical literature and discussions. The College also provided him with opportunities to lecture and to engage in the ongoing debates about medical theory and practice.

Harvey’s appointment as a physician at St. Bartholomew’s Hospital in 1607 marked another significant milestone in his career. St. Bartholomew’s, founded in 1123, was one of London’s oldest and most respected hospitals. Working at such an institution gave Harvey access to a wide range of patients, many of whom presented with complex and challenging cases. This experience was invaluable for a physician with Harvey’s ambitions, as it allowed him to hone his diagnostic and therapeutic skills while also deepening his understanding of human anatomy and physiology.

In 1609, Harvey married Elizabeth Browne, the daughter of Lancelot Browne, a prominent London physician who had served as the personal physician to Queen Elizabeth I. The marriage brought Harvey into contact with some of the most influential figures in English society, and it likely helped to further his career. Elizabeth was known for her intelligence and her interest in Harvey’s work, and their marriage appears to have been a supportive partnership, although they had no children.

During the early years of his career, Harvey was increasingly drawn to the study of the circulatory system, a topic that had fascinated him since his days in Padua. He began conducting a series of experiments on animals, carefully dissecting their bodies to observe the flow of blood through the heart and blood vessels. These experiments led him to question the prevailing medical theories of the time, particularly the Galenic model, which held that blood was continuously produced by the liver and then consumed by the body’s tissues.

Harvey’s experiments suggested a different model, one in which blood circulated through the body in a closed loop, driven by the pumping action of the heart. This idea was revolutionary, as it challenged the authority of Galen, whose teachings had dominated medical thought for over a thousand years. However, Harvey was cautious about making his findings public, knowing that they would likely provoke controversy.

In 1615, Harvey was appointed Lumleian Lecturer in Anatomy and Surgery at the Royal College of Physicians, a position that allowed him to share his ideas with a select audience of medical professionals. In his lectures, he began to outline his theory of blood circulation, although he continued to refine his ideas through further experimentation. Harvey’s work during this period laid the foundation for his most significant contribution to medical science, the publication of “De Motu Cordis” in 1628.

The Discovery of Blood Circulation (1628)

The publication of “Exercitatio Anatomica de Motu Cordis et Sanguinis in Animalibus,” commonly known as “De Motu Cordis” (An Anatomical Exercise on the Motion of the Heart and Blood in Animals), in 1628 marked a turning point in the history of medicine. In this groundbreaking work, William Harvey presented his theory of blood circulation, a discovery that would revolutionize the understanding of the human body and challenge centuries of established medical thought.

Harvey’s work was the culmination of over a decade of meticulous experimentation and observation. He had dissected numerous animals, including mammals, birds, and reptiles, to study the movement of blood within their bodies. Harvey’s experiments were guided by a careful, methodical approach that emphasized the importance of direct observation and empirical evidence. He was determined to understand the true nature of the circulatory system, even if it meant questioning the long-accepted teachings of Galen.

One of the most significant insights in Harvey’s work was the concept of the circulatory system as a closed loop. Harvey demonstrated that the heart acted as a pump, propelling blood through the arteries to the rest of the body and then returning it to the heart through the veins. He showed that the amount of blood being pumped by the heart was far greater than the amount that could be produced by the liver and consumed by the tissues, as suggested by the Galenic model. This led him to conclude that the blood must be circulating continuously, rather than being constantly produced and consumed.

Harvey’s observations also provided a new understanding of the function of the heart and blood vessels. He described the heart as a muscular organ that contracts and relaxes in a rhythmic cycle, propelling blood through the body with each beat. He also explained the role of the valves in the heart, noting how they prevented the backflow of blood, ensuring that it flowed in one direction through the circulatory system. These insights were revolutionary, as they directly contradicted the prevailing views of the time, which were based on Galen’s teachings from the 2nd century.

One of the key experiments Harvey conducted to support his theory involved tying off blood vessels to observe the effects on blood flow. For example, by applying a tourniquet to the arm, Harvey demonstrated that the veins would swell with blood, but the arteries would not, proving that blood flowed from the arteries into the veins. This experiment, along with others, provided clear, empirical evidence for his theory of circulation.

Despite the strength of his evidence, Harvey was aware that his findings would be controversial. The medical community in the early 17th century was deeply conservative, and many physicians were reluctant to abandon the teachings of Galen, who had been revered as the ultimate authority on medicine for over a millennium. Harvey’s challenge to this orthodoxy was bold and risky, and he knew that it would be met with skepticism and resistance.

Indeed, when “De Motu Cordis” was published, it sparked intense debate within the medical community. Some of Harvey’s contemporaries praised his work as a groundbreaking contribution to medical science, while others dismissed it as heresy. The opposition was particularly strong among older physicians who had built their careers on Galenic principles. They accused Harvey of being disrespectful to tradition and of promoting dangerous ideas that could undermine the entire foundation of medical knowledge.

Harvey, however, was undeterred by the criticism. He continued to defend his theory through lectures and debates, always relying on the strength of his empirical evidence. He was confident that his findings were correct and that, over time, they would be accepted by the broader scientific community. Harvey’s approach to science—his reliance on observation, experimentation, and logical reasoning—was a precursor to the modern scientific method, and it set a new standard for how medical research should be conducted.

Over the years, Harvey’s theory of circulation gradually gained acceptance, particularly among the younger generation of physicians and scientists who were more open to new ideas. His work laid the groundwork for further advances in physiology and medicine, including the discovery of the capillaries by Marcello Malpighi in 1661, which provided the missing link in Harvey’s theory by showing how blood moved from the arteries to the veins.

In addition to its impact on medicine, Harvey’s discovery of blood circulation had broader implications for the understanding of life itself. By showing that the body operated as a complex, interconnected system with the heart as its central engine, Harvey’s work helped to shift the perception of the human body from that of a static, unchanging entity to a dynamic, self-regulating organism. This new perspective would influence not only medicine but also biology, philosophy, and even the emerging field of mechanical engineering.

“De Motu Cordis” remains one of the most important works in the history of science. It represents the culmination of Harvey’s lifelong dedication to understanding the natural world and his willingness to challenge established ideas in the pursuit of truth. Through his work, Harvey not only revolutionized medicine but also demonstrated the power of the scientific method as a tool for uncovering the mysteries of nature.

Later Life and Contributions to Medicine (1629-1657)

Following the publication of “De Motu Cordis” in 1628, William Harvey’s reputation as one of the leading physicians and scientists of his time was firmly established. Despite the initial controversy surrounding his theory of blood circulation, Harvey continued to practice medicine and to make significant contributions to the field.

One of Harvey’s most notable appointments came in 1630 when he was named Physician Extraordinary to King Charles I. This prestigious position placed him at the heart of the English court, where he had the opportunity to treat members of the royal family and other high-ranking officials. Harvey’s role as the king’s personal physician further enhanced his status and provided him with access to the latest medical knowledge and resources.

Harvey’s association with the royal court also had its challenges, particularly during the tumultuous period leading up to the English Civil War (1642-1651). As a royalist, Harvey remained loyal to King Charles I throughout the conflict, a decision that would have significant consequences for his personal and professional life. During the war, Harvey accompanied the king on several military campaigns, serving as his physician and providing medical care to wounded soldiers.

One of the most dramatic episodes of Harvey’s life occurred during the Battle of Edgehill in 1642, the first major battle of the Civil War. According to contemporary accounts, Harvey was present on the battlefield, tending to the king’s sons, who had been entrusted to his care. While the battle raged around him, Harvey reportedly sat under a tree with the young princes, calmly reading a book, a testament to his composure under pressure. Although the battle ended in a stalemate, it marked the beginning of a long and bloody conflict that would have profound implications for England and for Harvey himself.

The war took a heavy toll on Harvey’s fortunes. As a supporter of the royalist cause, he faced hostility from the victorious Parliamentarians, who seized much of his property. Despite these hardships, Harvey remained committed to his medical practice and continued to conduct research. However, the political and social upheaval of the time made it difficult for him to focus on his scientific work, and he published little after “De Motu Cordis.”

In the later years of his life, Harvey turned his attention to other areas of medicine and natural philosophy. One of his lesser-known but still significant contributions was his work on embryology, the study of the development of embryos. Harvey’s research in this area was influenced by his mentor at Padua, Girolamo Fabricius, who had studied the development of animals. In his book “Exercitationes de Generatione Animalium” (Exercises on the Generation of Animals), published in 1651, Harvey presented his observations on the development of embryos in various species.

Harvey’s work in embryology was groundbreaking for its time, as it challenged the prevailing belief in preformationism, the idea that organisms develop from miniature versions of themselves. Instead, Harvey argued for epigenesis, the theory that embryos develop gradually through a series of stages. Although his ideas were not immediately accepted, they laid the foundation for future research in developmental biology and influenced later scientists such as Karl Ernst von Baer and Charles Darwin.

Harvey’s contributions to medicine and science were recognized during his lifetime, and he was honored by many of his contemporaries. In 1651, he was elected as a Fellow of the Royal Society, an institution that would later become one of the most prestigious scientific organizations in the world. The Royal Society was founded in 1660, shortly after Harvey’s death, and it represented the growing importance of scientific inquiry and experimentation in English intellectual life.

In his later years, Harvey also became increasingly interested in the philosophical implications of his work. He engaged in correspondence with leading thinkers of his time, including René Descartes, who was fascinated by Harvey’s discovery of blood circulation. Harvey’s ideas about the body as a machine, with the heart as its central pump, resonated with Descartes’ mechanistic philosophy, which sought to explain natural phenomena in terms of physical laws and processes.

Despite the many challenges he faced, including the loss of property and the political turmoil of the Civil War, Harvey remained dedicated to the pursuit of knowledge until the end of his life. He continued to practice medicine and to mentor younger physicians, passing on his empirical approach to the next generation. Harvey’s legacy as a physician, scientist, and thinker would endure long after his death, influencing the development of modern medicine and science.

William Harvey’s Death and Final Years

William Harvey’s final years were marked by continued dedication to his work, despite the political and social upheavals of his time. As the English Civil War came to a close and the monarchy was temporarily abolished, Harvey retreated from public life, focusing on his research and writing. He remained in close contact with the scientific community, offering advice and mentoring younger physicians, but he increasingly withdrew from active practice.

Harvey spent his last years living with his brothers, particularly Eliab Harvey, who had become a successful merchant. The Harvey family was well-off, which allowed William to live comfortably in his retirement. Although he was no longer directly involved in the political and courtly life that had characterized much of his earlier career, he maintained his intellectual interests and continued to write.

In 1651, Harvey published his second major work, “Exercitationes de Generatione Animalium,” in which he explored the processes of reproduction and embryonic development. This work further demonstrated Harvey’s commitment to understanding the natural world through observation and experimentation, and it solidified his reputation as one of the foremost scientists of his time.

Harvey’s health began to decline in his later years. By the early 1650s, he suffered from bouts of gout and other ailments that gradually weakened him. Despite these challenges, he remained mentally sharp and continued to correspond with colleagues and engage in scientific discussions.

On June 3, 1657, William Harvey passed away at the age of 79. He died peacefully at his brother Eliab’s house in Roehampton, London. His death marked the end of an era in medicine, but his legacy would live on through his groundbreaking work and the generations of physicians and scientists he had influenced.

Harvey was buried in the family vault in the church of St. Andrew’s in Hempstead, Essex, where his tomb can still be seen today. His epitaph, written in Latin, honors him as the man who discovered the nature of the blood and the motion of the heart, a fitting tribute to a life dedicated to the pursuit of knowledge.

In the centuries since his death, William Harvey has been celebrated as one of the most important figures in the history of medicine. His discoveries laid the foundation for modern physiology and cardiology, and his methods helped to establish the scientific approach that continues to drive medical research. Harvey’s influence is still felt today, not only in the field of medicine but also in the broader scientific community, where his commitment to observation, experimentation, and critical thinking remains a guiding principle.

Legacy and Influence on Modern Medicine

William Harvey’s discovery of blood circulation is often regarded as one of the most important milestones in the history of medicine. His work not only revolutionized the understanding of the human body but also laid the groundwork for the development of modern physiology, cardiology, and medical science as a whole.

One of the most significant aspects of Harvey’s legacy is his pioneering use of the scientific method. By emphasizing the importance of observation, experimentation, and logical reasoning, Harvey set a new standard for how medical research should be conducted. His empirical approach to the study of the body helped to shift the focus of medicine from reliance on ancient authorities to a more dynamic and evidence-based practice. This shift was instrumental in the eventual development of modern medical science, which relies on rigorous testing and experimentation to advance knowledge and improve patient care.

Harvey’s work also had a profound impact on the field of physiology, the study of how the body functions. Before Harvey’s discovery, the prevailing view of the body was largely static, with little understanding of how its various systems interacted. Harvey’s concept of the circulatory system as a closed loop, with the heart acting as a central pump, introduced the idea of the body as an interconnected, self-regulating system. This new perspective paved the way for further discoveries about the body’s various functions, including respiration, digestion, and the nervous system.

In addition to his contributions to physiology, Harvey’s work also laid the foundation for the field of cardiology, the study of the heart and its functions. His detailed observations of the heart’s structure and its role in pumping blood through the body provided the first accurate understanding of how the heart works. This knowledge has been crucial for the development of treatments for heart disease, one of the leading causes of death worldwide. Today, cardiologists continue to build on Harvey’s work, using advanced technology to study the heart and develop new therapies for cardiovascular conditions.

Harvey’s influence extended beyond the medical field, inspiring advancements in other areas of science and philosophy. His idea of the body as a machine, governed by physical laws and processes, resonated with the emerging mechanistic worldview of the 17th century. This perspective, which sought to explain natural phenomena in terms of mechanical principles, was central to the scientific revolution and the development of modern science. Thinkers like René Descartes and Isaac Newton were influenced by Harvey’s work, as it provided a model for understanding the natural world through empirical observation and experimentation.

Harvey’s legacy also includes his contributions to the development of medical education. His empirical approach to medicine emphasized the importance of hands-on experience and direct observation, principles that became central to the training of future physicians. Medical students today continue to learn from Harvey’s methods, as they are taught to observe patients, conduct experiments, and critically evaluate evidence.

One of the most enduring aspects of Harvey’s influence is the way he challenged and ultimately overturned long-standing medical doctrines. His work exemplifies the power of questioning established ideas and seeking new knowledge, even in the face of opposition. This spirit of inquiry and skepticism is at the heart of scientific progress, and Harvey’s willingness to challenge the status quo serves as an inspiration to scientists and physicians to this day.

Harvey’s impact on medicine is also evident in the numerous honors and commemorations that have been bestowed upon him. Hospitals, medical schools, and research institutions around the world bear his name, reflecting the deep respect and admiration that the medical community holds for his contributions. In the UK, the William Harvey Hospital in Ashford, Kent, stands as a tribute to his legacy, providing care to thousands of patients each year.

Moreover, Harvey’s work has been the subject of numerous books, articles, and studies, highlighting his role as a central figure in the history of medicine. Scholars continue to explore his life and work, shedding light on his methods, discoveries, and the broader context in which he lived. Harvey’s story is often used as a case study in the history of science, illustrating how new ideas can emerge from careful observation, rigorous experimentation, and a willingness to challenge prevailing beliefs.

In addition to his scientific contributions, Harvey is remembered for his character and personal qualities. Described by contemporaries as modest, diligent, and deeply committed to his work, Harvey embodied the ideals of a true scientist. He was not driven by the desire for fame or recognition, but by a genuine curiosity and a passion for understanding the natural world. This humility, combined with his intellectual rigor, made him a respected and admired figure among his peers.

Harvey’s influence on medicine and science cannot be overstated. His discovery of blood circulation was a turning point in the history of medicine, opening the door to new ways of thinking about the human body and its functions. His methods laid the groundwork for the development of modern scientific practices, and his legacy continues to inspire generations of scientists and physicians.

As we reflect on Harvey’s contributions, it is important to recognize the broader impact of his work on our understanding of life itself. By revealing the inner workings of the circulatory system, Harvey helped to demystify the human body, showing that it operated according to natural laws that could be observed, understood, and manipulated. This realization was a crucial step in the development of modern biology and medicine, and it has had far-reaching implications for how we approach health, disease, and the study of life.