Throughout history, humanity has repeatedly redrawn the map of the solar system. Planets have been discovered, celebrated, debated, downgraded, and sometimes erased entirely—not because they physically vanished, but because our understanding of the universe changed. Long before space probes and precision telescopes, astronomers relied on imperfect observations, mathematical predictions, and bold imagination. In that process, several “planets” were proposed, named, and even taught as real worlds, only to later disappear from scientific consensus.

These forgotten planets are not mistakes to be mocked. Each emerged from serious scientific reasoning based on the best knowledge of its time. Each played a role in pushing astronomy forward, forcing better measurements, sharper theories, and deeper humility. Some were hypothesized to explain unexplained motions. Others arose from incomplete data. A few lingered for centuries before finally fading away.

This article explores six such forgotten planets—worlds that once held a place in the solar system but were ultimately removed. Their stories reveal not only how science corrects itself, but how human curiosity, error, and persistence are inseparably linked.

1. Vulcan: The Planet That Lived Inside Mercury’s Orbit

Few forgotten planets have a story as dramatic as Vulcan. For nearly half a century in the nineteenth century, Vulcan was widely believed to exist. It was not a fringe idea; it was proposed by one of the most respected mathematicians and astronomers of the era.

The story begins with Mercury. Astronomers noticed that Mercury’s orbit behaved strangely. Its closest point to the Sun, known as the perihelion, slowly shifted over time. Most of this shift could be explained by the gravitational pull of other planets, but a small portion remained unexplained. This discrepancy was tiny, yet persistent, and it troubled astronomers deeply.

In 1859, the French mathematician Urbain Le Verrier proposed a solution. Just as he had previously predicted the existence of Neptune to explain irregularities in Uranus’s orbit, he suggested that another planet—smaller and closer to the Sun than Mercury—was responsible for Mercury’s anomalous motion. He named this hypothetical planet Vulcan, after the Roman god of fire.

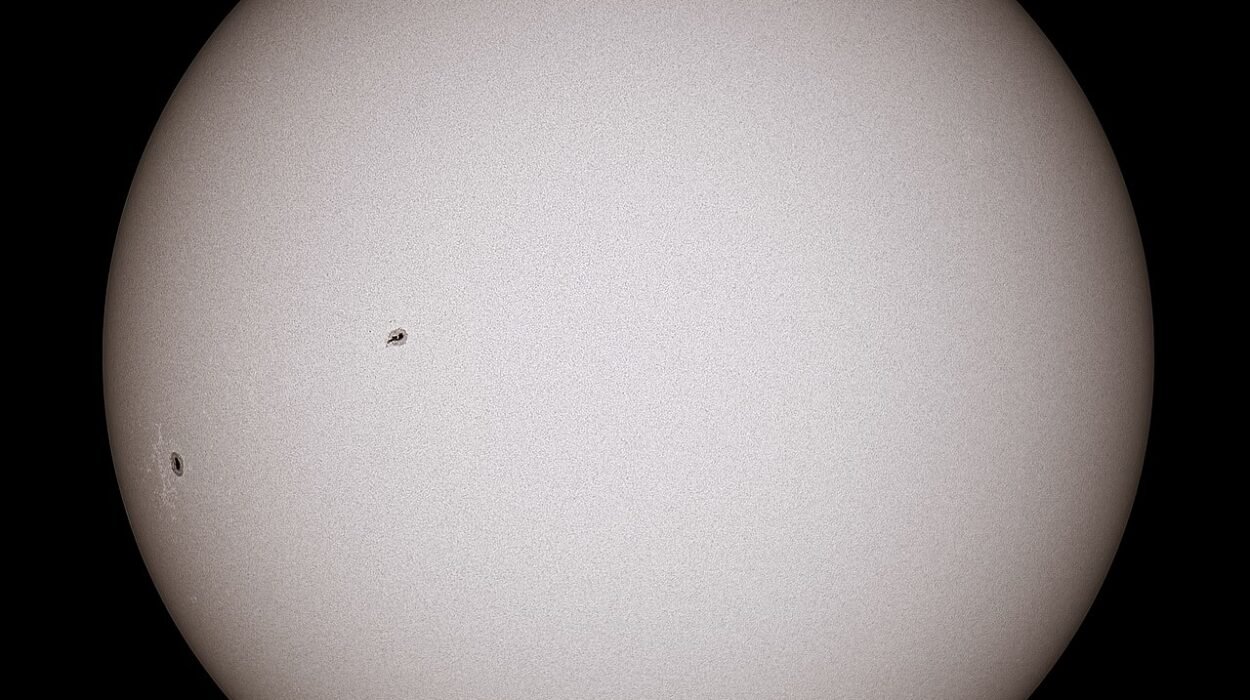

Reports soon followed of dark objects seen transiting the Sun, and several astronomers claimed sightings consistent with Vulcan’s predicted orbit. Some even calculated orbital parameters. Textbooks mentioned Vulcan. Observatories searched for it. For decades, Vulcan was treated as a legitimate member of the solar system.

Yet Vulcan was elusive. Observations were inconsistent, and no single object could be reliably tracked. The turning point came in 1915, when Albert Einstein published his general theory of relativity. Einstein showed that Mercury’s orbital anomaly was not caused by an unseen planet, but by the curvature of spacetime near the Sun. General relativity predicted Mercury’s motion exactly, without invoking Vulcan.

With that, Vulcan vanished—not from space, but from science. It remains a powerful reminder that unexplained data can point either to new objects or to deeper laws. Vulcan’s disappearance marked not a failure, but a triumph of physics.

2. Planet X: The World That Refused to Stay Found

Planet X is unusual among forgotten planets because it was both discovered and undiscovered multiple times. The name refers not to a single object, but to a persistent idea: that something massive lurks beyond the known planets, influencing their orbits.

The concept emerged in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, when astronomers noticed apparent irregularities in the motions of Uranus and Neptune. These anomalies seemed similar to those that had led to Neptune’s discovery, suggesting the gravitational influence of another, more distant planet.

Percival Lowell, an influential American astronomer, devoted years to searching for this hypothetical world, which he called Planet X. After Lowell’s death, his observatory continued the search, and in 1930, Clyde Tombaugh discovered Pluto. Initially, Pluto was celebrated as Planet X, the long-sought ninth planet.

However, as measurements improved, it became clear that Pluto was far too small to account for the supposed orbital discrepancies. Even more unsettling, the discrepancies themselves gradually disappeared as astronomers refined planetary mass estimates and observational data. The mathematical need for Planet X faded away.

Yet the idea refused to die. Throughout the twentieth century, astronomers periodically revived Planet X to explain various anomalies, only to abandon it again when better data resolved the issue. In recent years, the concept has resurfaced in a new form, with the hypothesis of a distant “Planet Nine” proposed to explain unusual clustering in the orbits of distant icy objects.

Whether Planet Nine exists remains unknown. But the original Planet X—the gravitational ghost haunting Uranus and Neptune—has effectively been forgotten. Its story illustrates how scientific hypotheses evolve, merge, and sometimes dissolve entirely as evidence improves.

3. Phaeton: The Planet That Became an Asteroid Belt

Long before the discovery of asteroids, astronomers noticed something curious: a large gap between the orbits of Mars and Jupiter. In the late eighteenth century, this gap seemed suspicious, especially given a numerical pattern known as the Titius-Bode law, which appeared to predict the spacing of planets.

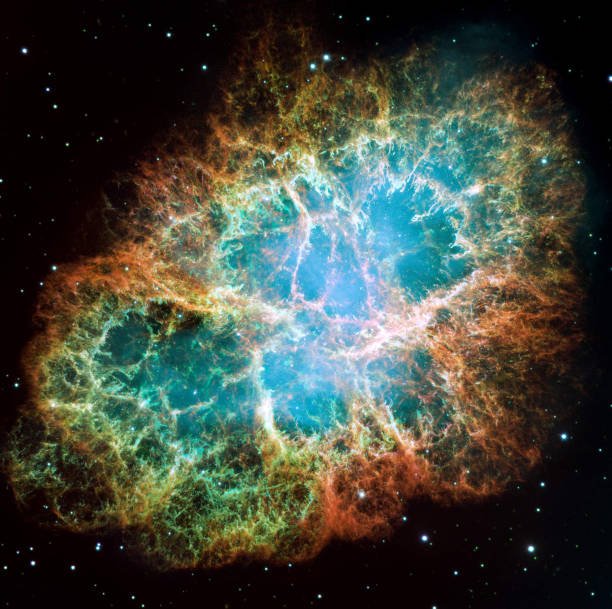

Many astronomers concluded that a planet must once have existed in this region. This hypothetical world was named Phaeton, after the mythological figure who lost control of the Sun’s chariot and was destroyed. The name was fitting, because Phaeton was imagined as a planet that had somehow been shattered.

The discovery of the first asteroids—Ceres, Pallas, Juno, and Vesta—initially strengthened this idea. These objects were seen as fragments of the destroyed planet. For much of the nineteenth century, textbooks and scientific discussions described the asteroid belt as the remains of Phaeton.

Over time, however, this interpretation collapsed. Physics showed that the combined mass of all asteroids is far too small to represent a destroyed planet. Moreover, models of planetary formation demonstrated that Jupiter’s immense gravity likely prevented a planet from ever forming in that region in the first place.

Phaeton was not destroyed because it never existed. The asteroid belt is now understood as primordial debris left over from planet formation, not planetary ruins. Still, Phaeton’s story reflects humanity’s instinct to impose narrative explanations on incomplete data—and the willingness of science to abandon those narratives when evidence demands it.

4. Theia: The Planet That Lives On as the Moon

Unlike most forgotten planets, Theia is not rejected because it was wrong, but because it no longer exists as a separate world. Theia is the name given to a hypothesized planet that played a central role in one of the most important events in Earth’s history: the formation of the Moon.

According to the giant impact hypothesis, a Mars-sized protoplanet collided with the early Earth roughly 4.5 billion years ago. This catastrophic impact ejected enormous amounts of material into orbit around Earth, eventually coalescing to form the Moon. The impacting body has been named Theia.

Theia is “forgotten” in a literal sense. If it existed, it no longer does. Its matter is now part of Earth and the Moon. No direct physical trace of Theia remains as a distinct object, yet its legacy shapes our planet profoundly.

This hypothesis is supported by multiple lines of evidence. The Moon’s composition closely resembles Earth’s mantle, consistent with a violent mixing event. Computer simulations show that such an impact can produce a Moon with the observed mass and orbital properties.

Theia represents a different kind of forgotten planet—a world whose existence is inferred from consequences rather than observation. It reminds us that planets can disappear not only from theory, but from reality itself, leaving behind altered worlds in their wake.

5. Counter-Earth: The Planet Always Hidden Behind the Sun

Counter-Earth is one of the most intriguing forgotten planets because it was rooted as much in philosophy as in observation. Originating in ancient Greek thought, particularly among followers of Pythagoras, Counter-Earth was proposed as a planet that shared Earth’s orbit but always remained on the opposite side of the Sun, permanently hidden from view.

This idea was not based on telescopic evidence, but on a belief in cosmic symmetry and harmony. The universe, it was argued, should be balanced, and Earth alone seemed insufficient. Counter-Earth restored numerical and philosophical order to the cosmos.

As astronomy advanced, the idea persisted sporadically, occasionally revived in speculative discussions. However, physics ultimately ruled it out. A planet sharing Earth’s orbit on the opposite side of the Sun would be gravitationally unstable over long timescales. Moreover, its gravitational effects on Earth and other planets would be detectable.

No such effects have ever been observed. Space probes and solar observations have conclusively eliminated the possibility of a hidden twin world. Counter-Earth survives only as a historical curiosity, illustrating how philosophical aesthetics once shaped scientific models—and how empirical evidence eventually replaced them.

6. Pluto as a Planet That Was, Then Was Not

Pluto occupies a unique position among forgotten planets because it was not hypothetical, nor was it imaginary. It is real, observable, and still orbiting the Sun. Yet in a profound cultural sense, Pluto has been forgotten as a planet.

Discovered in 1930, Pluto was celebrated as the ninth planet for more than seventy years. Generations grew up memorizing its name as the outermost member of the solar system. Yet even early on, Pluto was an oddity—smaller than Earth’s Moon, with a highly eccentric and inclined orbit.

As astronomical surveys expanded, scientists discovered many similar icy objects beyond Neptune. Pluto was no longer unique. It became clear that the solar system contained a vast population of such bodies, now known as the Kuiper Belt.

In 2006, the International Astronomical Union redefined the term “planet.” Under the new definition, Pluto failed to meet one criterion: it had not cleared its orbital neighborhood of other objects. Pluto was reclassified as a dwarf planet.

Scientifically, this decision reflected improved understanding of solar system structure. Emotionally, it was deeply controversial. Pluto’s demotion revealed how attached humans become to scientific categories, even when those categories evolve.

Pluto is not gone, but its planetary status is. It stands as a reminder that scientific classifications are tools, not truths—and that even familiar worlds can be redefined as knowledge grows.

Conclusion: What Forgotten Planets Teach Us About Science

The six forgotten planets explored here never truly existed in the same way Earth or Mars does—or no longer exist at all. Yet each played a meaningful role in the development of astronomy. They motivated observations, refined theories, and exposed the limits of human understanding.

Science advances not by avoiding error, but by confronting it. Forgotten planets are the fossil record of scientific thought, preserving moments when imagination outran evidence, or when evidence pointed in misleading directions. Their disappearance marks progress, not failure.

These lost worlds also remind us that the solar system is not just a physical structure, but a human story—one shaped by curiosity, belief, revision, and humility. As new discoveries await beyond the edges of current knowledge, future generations may look back on today’s certainties as tomorrow’s forgotten planets.

In that sense, forgetting is not the opposite of knowing. It is part of knowing more.