From the moment humanity first looked upward, the question has lingered in our collective imagination: what is the shape of everything? We stand on a small blue planet, surrounded by stars that seem to go on forever, and yet our minds hunger to know what lies beyond the horizon of sight. Is the universe infinite—stretching endlessly in all directions? Is it curved back upon itself, forming a vast cosmic loop? Or is it flat, expanding without edge or boundary?

The question is ancient, but the pursuit of its answer is deeply modern. With telescopes that see across billions of light-years, satellites that measure invisible ripples in spacetime, and equations that describe the universe as both wave and geometry, we are closer than ever to understanding what “everything” looks like.

But the truth is stranger, and more beautiful, than anyone could have imagined.

The Cosmic Canvas

Imagine the universe as a vast, ever-expanding painting. Galaxies swirl like brushstrokes across an invisible canvas; stars flicker like splattered light. Yet what we see is only the surface—an image projected on something deeper. The canvas itself, the structure upon which the cosmos is drawn, is the very shape of space.

To understand the universe’s shape, we must first understand space itself. Space is not a passive void, not an empty nothingness waiting to be filled. It is an active entity—a dynamic, elastic fabric that can stretch, bend, and twist. Einstein’s theory of general relativity revealed this truth a century ago: gravity is not a force acting at a distance, but the curvature of spacetime caused by mass and energy.

In this view, everything from the fall of an apple to the orbit of galaxies arises because space tells matter how to move, and matter tells space how to curve. If space can curve locally—around stars and planets—then perhaps it can also curve on the grandest scale. The shape of the universe, then, is the shape of space itself.

The Universe and Its Geometry

Geometry, in the cosmic sense, describes how space behaves on large scales. Does parallel light remain parallel forever, or do the beams eventually converge or diverge? The answer reveals whether the universe is closed, open, or flat.

If the universe is closed, its geometry resembles a sphere. Imagine living on the surface of a balloon: you could travel in a straight line and, given enough time, return to your starting point without ever encountering an edge. In a closed universe, space curves back on itself, and the total volume is finite.

If the universe is open, it is shaped more like a saddle. Parallel lines diverge, and space curves outward. In such a universe, there is no limit—it extends infinitely in all directions, yet has negative curvature, like a vast cosmic canyon that never ends.

Finally, if the universe is flat, it has no overall curvature. Parallel lines remain parallel, triangles add up to 180 degrees, and geometry behaves exactly as Euclid described it thousands of years ago. A flat universe can still be infinite, but its geometry is perfectly balanced—neither curving inward nor outward.

These are not merely abstract possibilities. Each represents a distinct destiny for the cosmos. A closed universe might one day stop expanding and collapse in a “Big Crunch.” An open universe would expand forever, growing ever colder and emptier. A flat universe, poised delicately between these two extremes, could expand eternally—but at a rate finely tuned by its total energy.

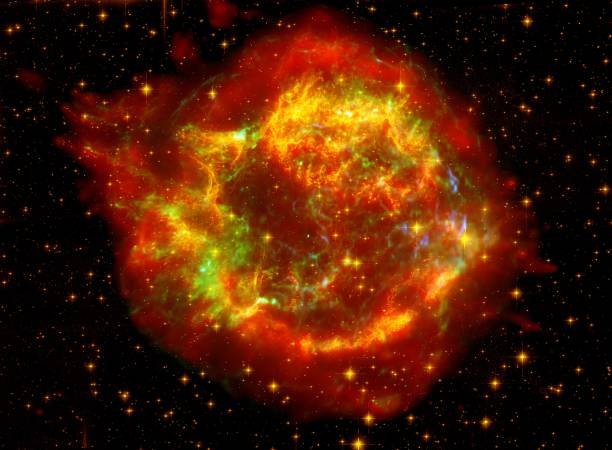

The Echo of the Big Bang

To determine the shape of the universe, astronomers look back in time to its very birth. The Big Bang wasn’t an explosion into space—it was the expansion of space itself, a swelling of the cosmic fabric from an unimaginably hot and dense beginning. As the universe expanded, it cooled, and light began to travel freely for the first time.

That ancient light still fills the cosmos today, though it has stretched into microwaves over billions of years of expansion. This faint glow is the Cosmic Microwave Background, or CMB—a fossilized whisper from the universe’s infancy, just 380,000 years after the Big Bang.

The CMB is one of the most precious sources of information in all of science. It tells us about the universe’s age, composition, and—most crucially—its geometry. When scientists measure the patterns in this cosmic radiation, they can determine whether space bends light one way or another.

What they found was astonishing. The data from satellites like WMAP and Planck show that, to an extraordinary degree of precision, the universe appears flat. The angles of cosmic patterns behave exactly as they would in a Euclidean geometry. Space, it seems, is balanced on the razor’s edge between curvature and chaos.

Flatness and the Fine-Tuning of the Cosmos

A flat universe may sound ordinary, but it is anything but. For space to be flat, the total density of matter and energy must be precisely equal to a critical value. Too much density, and gravity would pull everything inward, curving the universe into a sphere. Too little, and expansion would stretch space into an open saddle.

That the universe today is so nearly flat suggests an incredible fine-tuning. Even a tiny deviation in the early universe would have amplified over time, leading to a very different cosmos. So how did it remain so perfectly balanced?

The answer, many physicists believe, lies in a theory called cosmic inflation. According to inflation, a fraction of a second after the Big Bang, the universe expanded exponentially, faster than the speed of light. This rapid stretching smoothed out any curvature or irregularities, flattening the cosmos much like a balloon that, once inflated enough, appears flat to an observer standing upon it.

Inflation not only explains flatness but also accounts for the uniformity of the CMB and the distribution of galaxies. It suggests that what we see as the “observable universe” is just a tiny patch of a vastly larger, perhaps infinite, cosmos.

The Observable Universe Versus the Whole

When we speak of the universe’s shape, we must make an important distinction: the universe we can see and the universe that is.

The observable universe is limited by light’s finite speed and the age of the cosmos. Light from the most distant galaxies has traveled about 13.8 billion years to reach us, but because space itself has been expanding, the farthest observable regions are now roughly 46 billion light-years away in every direction. Beyond that, light has not had time to arrive.

But the entire universe—the totality of existence—may extend far beyond what we can observe, perhaps infinitely. The shape we infer from our visible bubble may be only a local curvature, not the global truth.

It’s like standing on a calm sea. The water appears flat as far as the eye can see, yet over vast distances, the ocean follows the curve of Earth. Similarly, space might appear flat locally but curve on unimaginable scales.

This leads to one of the most profound realizations in science: we may never be able to measure the universe’s full shape. Our cosmic horizon, set by the speed of light and the passage of time, may forever confine us to a partial view of the whole.

The Strange Possibility of a Finite but Unbounded Universe

One of Einstein’s most beautiful insights was that space could be finite yet unbounded. This idea is counterintuitive but deeply elegant. Imagine a two-dimensional being living on the surface of a sphere. To that creature, space seems to go on endlessly—it can travel in any direction without encountering an edge. And yet the surface is finite; it wraps around itself.

Our universe could be similar in three dimensions. If space is curved positively—like a higher-dimensional sphere—it could be finite in volume but without boundaries. You could, in theory, travel in a straight line and eventually return to your starting point, having circumnavigated the cosmos.

This concept of a finite but unbounded universe challenges our intuition about infinity and edges. It tells us that “endless” does not necessarily mean “infinite.” The universe could have no walls or borders, yet still contain a finite amount of matter and energy.

So far, however, observations do not show any sign of such curvature. If the universe does wrap around itself, it does so on scales far larger than what we can observe.

Beyond Flatness: Exotic Topologies

Even if the universe is geometrically flat, its topology—its connectivity—could be far stranger. Space could be shaped like a torus, a 3D version of a doughnut, where traveling in one direction eventually brings you back from another. It could twist and fold in higher dimensions, forming patterns beyond human visualization.

Some cosmologists have proposed that space might contain repeating structures, like a hall of mirrors, where galaxies and stars reappear in multiple locations due to the looping nature of the cosmos. If true, the night sky might contain copies of the same galaxy, seen from different directions and times.

Though evidence for such exotic topologies remains elusive, the mere possibility reminds us how profoundly mysterious the universe still is. Geometry may describe space, but topology reveals its soul.

Dark Matter, Dark Energy, and the Shape of Fate

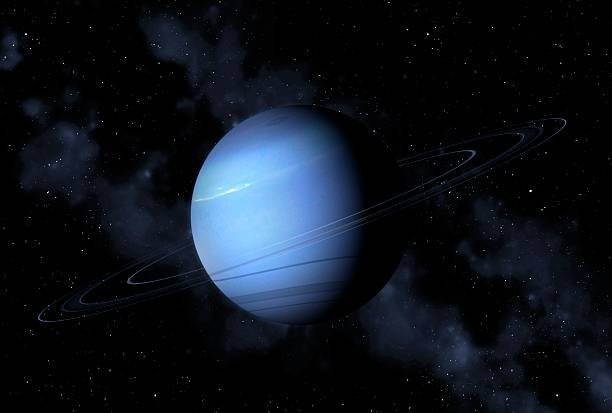

The shape of the universe is intimately tied to its content—what it’s made of and how much of it exists. Yet when we measure the cosmos, we discover a surprising truth: most of it is invisible.

Only about five percent of the universe consists of ordinary matter—the atoms that make stars, planets, and people. Another 27 percent is dark matter, an unseen substance that exerts gravity but does not emit light. And an astonishing 68 percent is dark energy, a mysterious force driving the accelerated expansion of the universe.

It is this dark energy that determines the ultimate destiny—and thus the ultimate shape—of the cosmos. If dark energy remains constant, the universe will continue expanding forever, growing emptier as galaxies drift apart. If it changes over time, the universe could slow, collapse, or even rip itself apart in a “Big Rip,” where space expands faster than matter can hold together.

Our current observations suggest a flat universe dominated by dark energy, expanding eternally into a cold, dark future. But dark energy’s true nature remains one of the deepest puzzles in science. Until we understand it, the universe’s fate—and perhaps its true shape—will remain uncertain.

The Multiverse and Beyond

What if our universe is not the only one? The theory of inflation naturally leads to the idea of a multiverse—a vast collection of universes, each with its own laws, constants, and geometry. In some, space might be closed and finite; in others, open and infinite.

If inflation occurred in many regions of space, then new universes could continually bubble into existence like foam on a cosmic sea. We inhabit just one bubble, whose local shape happens to be nearly flat. Beyond it, other bubbles may curve differently, or not at all.

The multiverse idea is both exhilarating and unsettling. It challenges our sense of uniqueness and raises profound philosophical questions. If countless universes exist, each with different physical laws, what does it mean to say “the universe” has a single shape? Perhaps the concept of “shape” itself becomes too small to describe reality.

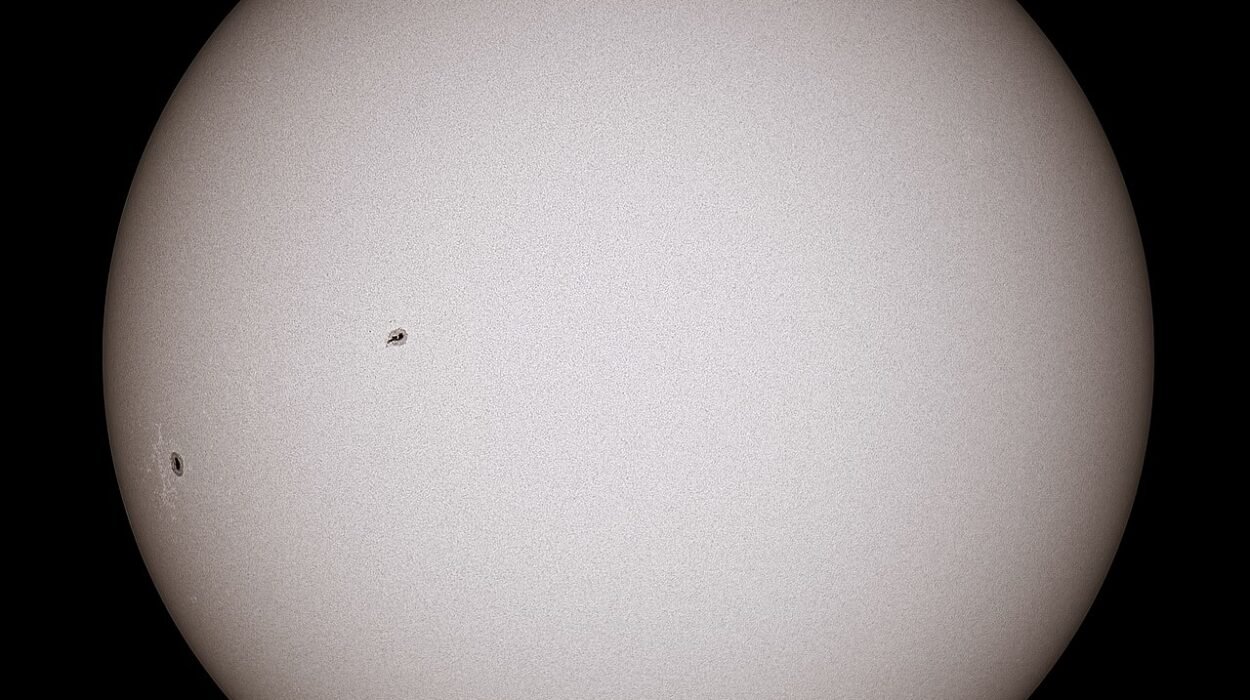

When the Universe Feels Flat—But Isn’t

Even if the universe appears flat, small deviations might exist. Measurements of the CMB have revealed minute fluctuations—ripples of temperature and density frozen from the universe’s earliest moments. These ripples seeded the formation of galaxies and clusters, but they also carry subtle clues about curvature.

Current data suggest that if there is curvature, it is so slight that the radius of curvature must be hundreds of times larger than the observable universe. To us, that would feel indistinguishable from infinite flatness.

It’s like standing on a vast plain so enormous that no matter how far you walk, the horizon always looks flat. You’d never see the curvature—even though it exists. That might be our situation: living on a small patch of a grand cosmic surface, too immense to ever fully comprehend.

The Human Imagination Versus the Infinite

The idea of infinity has always haunted the human mind. We are finite beings, living brief lives on a small planet, yet we dare to conceive of endlessness. To speak of an infinite universe is to confront both awe and insignificance.

If the universe is infinite, then every possible configuration of matter could occur somewhere. There could be another version of you, reading this same sentence, on a planet circling a distant star. In an infinite cosmos, repetition is inevitable. The universe would become not just vast, but recursive—a hall of endless mirrors reflecting all possible realities.

And yet, even if the universe is finite, it remains incomprehensibly large. The observable cosmos alone contains more galaxies than there are grains of sand on all Earth’s beaches. Each galaxy holds billions of stars, each star potentially surrounded by worlds. Whether infinite or not, the universe’s scale transcends imagination.

Measuring the Unmeasurable

How do we measure the shape of something so vast that light itself can barely cross it? Scientists use ingenious techniques, from mapping the cosmic microwave background to studying the distribution of galaxies and gravitational lensing—the bending of light by massive structures.

By combining these measurements, cosmologists construct a picture of the universe’s geometry with astonishing precision. Yet every measurement is limited by distance, time, and uncertainty. We are like fish trying to infer the shape of the ocean from the ripples in our small pond.

Still, even our limited knowledge reveals profound truths. The fact that the universe is so nearly flat tells us something fundamental about its origin. It suggests that the cosmos began in a moment of exquisite symmetry, finely tuned to produce life and structure billions of years later.

The Shape of Time

Perhaps the universe’s shape cannot be separated from time itself. Just as space curves, time, too, can bend and stretch. The universe might not only have a spatial shape but a temporal one—a curvature of history that connects beginning and end in ways we cannot yet perceive.

Some theories propose that time could loop, that the Big Bang might one day mirror a “Big Bounce,” where a previous universe collapsed and rebirthed ours. Others imagine time as a one-way arrow, stretched infinitely forward by entropy.

Whatever the case, the shape of the universe is also the shape of its story—a narrative written across both space and time, from the first flash of creation to the farthest echoes of eternity.

The Universe as an Idea

As our understanding deepens, the universe becomes not just a physical object but an idea—a concept that bridges science and philosophy, mathematics and meaning. Its shape is not merely a matter of geometry but of perspective.

When we ask about the universe’s shape, we are also asking about our place within it. We are seeking the architecture of existence, the blueprint of reality itself. The cosmos, in all its immensity, reflects back our own longing to know where we belong.

And perhaps that’s the most extraordinary thing: that a species on a small planet can even conceive of such questions. That our fragile minds, born of stardust, can reach for the shape of infinity.

The Final Horizon

So, what is the shape of the universe? The best evidence we have tells us it is flat—an immense, expanding sheet of spacetime balanced perfectly between curvature and chaos. Yet this flatness may only be an illusion, a local truth within a grander reality that bends beyond our sight.

It could be infinite, stretching endlessly. It could be finite but unbounded, wrapping around itself in unseen dimensions. Or it could be something stranger still—something that transcends all human geometry.

Whatever its true form, the universe remains the greatest mystery ever encountered. Its shape is not only a question of science but of wonder, a reminder that we live within a cosmos both knowable and unfathomable.

As we gaze deeper into the night, measuring ancient light and tracing the curvature of time, we are not just exploring the universe—we are exploring the boundaries of thought itself.

Perhaps, in the end, the question of the universe’s shape is less about the cosmos and more about us. It is the shape of our curiosity, our imagination, and our endless desire to understand the infinite.

And that, too, is part of the universe’s geometry—the curve of consciousness within the grand expanse of everything.