Since the dawn of human consciousness, we have looked up at the stars and wondered: Is this all there is? For millennia, that question meant asking whether other worlds—other planets—might harbor life. But as science advanced, our curiosity grew more daring. We began to ask something far more profound, even unsettling: Could there be other universes beyond our own?

This question strikes at the very foundation of reality. It forces us to confront the limits of what we can see, what we can test, and even what we can imagine. If the universe we inhabit is not the only one—if ours is but one of many, perhaps infinitely many—then everything we think we know about existence could be just a small chapter in a much grander story.

The idea of parallel universes, or the “multiverse,” might sound like science fiction. Yet it emerges naturally from the mathematics of modern physics, from the strange rules of quantum mechanics to the vast expanses of cosmology. It is both a scientific hypothesis and a philosophical revolution—a concept that invites us to rethink what “reality” truly means.

In exploring this mystery, we are not just asking whether other worlds exist. We are asking whether reality itself might be far bigger, deeper, and stranger than our senses could ever reveal.

Seeds of the Multiverse: When Philosophy Met Science

The idea that reality might not be singular is not new. Ancient philosophers in Greece, India, and China speculated that the cosmos could be one among many. The atomists, like Democritus, imagined infinite worlds forming and dissolving in an eternal void. Hindu cosmology speaks of countless universes arising and perishing in the breath of Brahma.

For centuries, these were poetic musings—metaphysical dreams beyond verification. But in the modern era, as physics uncovered the laws governing our own universe, whispers of other realities began to emerge from the equations themselves.

When Einstein unveiled his general theory of relativity in 1915, he described a universe that could bend, stretch, and evolve. The cosmos was no longer static but dynamic—capable of expansion and transformation. This revelation set the stage for the Big Bang theory, which tells us that our universe began around 13.8 billion years ago in an immense burst of energy and space.

But if space can expand once, why not again? And if cosmic creation can happen once, why not endlessly? The seeds of the multiverse were hidden in that very logic.

The Big Bang and the Cosmic Horizon

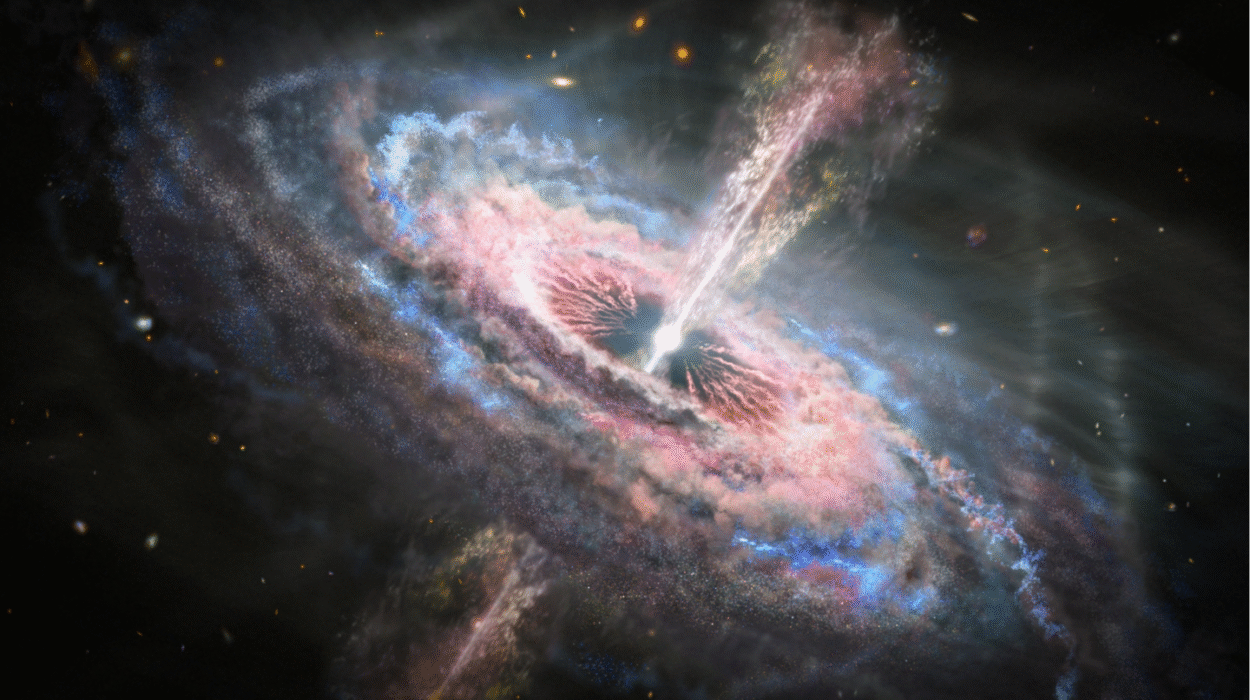

To understand why physicists began taking the idea of multiple universes seriously, we must first grasp what our own universe looks like. The Big Bang model tells us that space itself has been expanding since the beginning. Galaxies are not flying through space; space is stretching, carrying them apart.

But this expansion has limits. Because the universe has a finite age, light from the most distant regions has not yet reached us. That means there are parts of the cosmos forever beyond our sight—a cosmic horizon. Beyond that horizon, space and time continue. There could be galaxies, stars, even civilizations we will never detect because light cannot bridge the gulf between us.

Already, this suggests that what we call “the universe” might be just the visible patch of a much larger whole—a bubble of reality within an incomprehensible expanse.

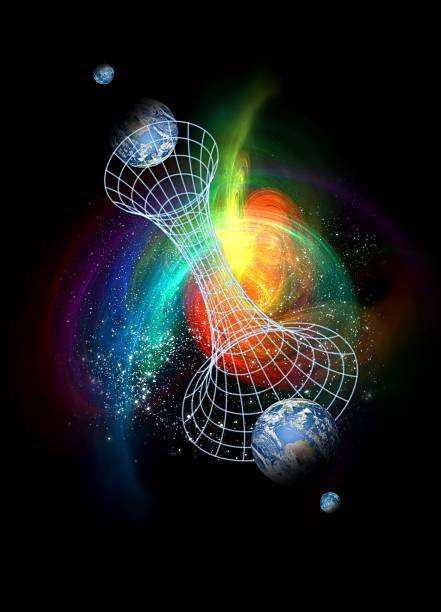

Now, imagine that our bubble is not alone. Imagine an infinite ocean of space where countless other bubbles expand, collide, and drift away. Each bubble could be a universe with its own laws of physics, its own galaxies, perhaps even its own versions of us. This is not fantasy—it is one of the leading interpretations of modern cosmology.

Inflation and the Birth of Cosmic Diversity

In the 1980s, a new theory emerged that transformed our understanding of the Big Bang: cosmic inflation. Proposed by physicist Alan Guth, inflation suggests that in the earliest fraction of a second after the Big Bang, the universe underwent a period of exponential expansion—space itself ballooned faster than the speed of light.

This sudden stretching explains why our universe is so smooth and uniform on large scales. It also predicts the existence of tiny quantum fluctuations—microscopic ripples in energy—that became the seeds of galaxies. But inflation has a startling implication: it may never completely stop.

According to “eternal inflation,” while inflation ends in some regions (creating universes like ours), it continues in others. This leads to a vast cosmic foam—an infinite series of bubble universes, each with its own laws, constants, and forms of matter.

In one universe, gravity might be stronger; in another, atoms might never form. In a few rare bubbles—like ours—the laws of physics allow for stars, planets, and life.

This vision, though breathtaking, is a natural consequence of inflationary theory. If true, our observable universe is just one bubble in an endless multiverse—a single spark in an eternal cosmic firework.

Quantum Mechanics: The Universe of Many Possibilities

If the multiverse of cosmology sounds vast, the multiverse of quantum mechanics is intimate—it lives inside every atom, every decision, every breath.

Quantum physics, which governs the microscopic world, tells us that particles do not exist in definite states until measured. An electron is not in one place or another—it is in a superposition of all possible locations. When we observe it, the wave of probabilities collapses into a single outcome.

But what if it doesn’t collapse at all? In the 1950s, physicist Hugh Everett proposed a radical idea—the Many-Worlds Interpretation. According to Everett, every possible quantum outcome actually occurs, but in separate, branching universes. When you flip a coin, and it can land heads or tails, the universe splits—one where you see heads, another where you see tails.

In this view, the universe is constantly branching at every moment, creating an unimaginable number of parallel realities. There could be versions of you who made different choices, lived different lives, loved different people. Every possibility that could happen does happen—somewhere.

Though this sounds fantastical, the Many-Worlds Interpretation is mathematically consistent with quantum mechanics. It requires no mysterious “collapse” of the wavefunction, only a vast, ever-branching reality.

If true, every moment births infinite versions of existence—a cosmic forest of realities growing endlessly with each quantum breath.

String Theory and Higher Dimensions

To unite the laws of the very large (relativity) and the very small (quantum mechanics), physicists developed string theory—a bold framework that reimagines the universe not as made of point-like particles, but tiny vibrating strings of energy.

In this theory, different vibrations of these strings correspond to different particles. But to make the equations work, string theory requires extra dimensions—perhaps ten or eleven in total. Most of these dimensions are curled up and invisible to us, but their presence may determine the very structure of our universe.

Here’s where things get astonishing: string theory allows for a vast “landscape” of possible universes, each corresponding to a different way the extra dimensions could be folded. The number of possible configurations may exceed 10^500—a number so vast it defies imagination.

Each configuration produces a universe with its own physical laws, constants, and particles. Ours is just one among this inconceivable landscape.

In other words, the equations of physics themselves might predict not one universe, but an infinite diversity of them—a mathematical multiverse.

The Mirror of Mathematics and Reality

When physicists find mathematical frameworks that describe multiple universes, a deep question arises: what makes one of them “real”? If the equations of string theory or quantum mechanics naturally contain many solutions, why should only one correspond to our world?

The more we learn, the more it seems that mathematics itself is not just a tool for describing reality—it is reality. The universe, perhaps, is a structure of pure logic and number, and within that logic, other realities may reside, unseen but no less real.

Some physicists, like Max Tegmark, go further, proposing the Mathematical Universe Hypothesis: that every consistent mathematical structure exists physically somewhere. In this radical view, every universe that can exist does exist. Reality becomes a vast library of all possible worlds.

Shadows of Other Universes in Our Sky

If parallel universes exist, can we ever detect them? Could there be evidence hidden in the cosmic microwave background—the faint afterglow of the Big Bang?

Some cosmologists think so. If our universe is one bubble among many, collisions between bubbles might leave subtle scars—circular patterns or temperature anomalies in the cosmic background radiation.

While no definitive evidence has yet been found, intriguing hints have occasionally appeared—mysterious cold spots, statistical oddities—that ignite scientific and public imagination. These could be chance fluctuations, or they could be the fingerprints of another universe brushing against ours.

Even gravitational waves—ripples in spacetime—could, in theory, carry echoes from beyond our cosmic horizon. Future experiments may reveal whether our universe’s birth was a solitary event or part of a grander multiversal symphony.

The Fine-Tuning Mystery

One of the most compelling arguments for the multiverse arises from the apparent “fine-tuning” of our universe. Many of the physical constants—such as the strength of gravity, the charge of the electron, or the cosmological constant—appear precisely balanced to allow the existence of stars, chemistry, and life.

If gravity were slightly stronger or weaker, the universe might collapse or expand too fast for life to form. If the strong nuclear force were different, atoms would not hold together. It’s as if our universe is delicately tuned for consciousness.

The multiverse offers a natural explanation. If there are countless universes with different physical laws, it’s not surprising that at least one of them—ours—happens to have the right conditions for life. We find ourselves in a universe that allows observers simply because we couldn’t exist anywhere else.

This is known as the anthropic principle—the idea that the universe’s properties appear special because we are here to observe them. It’s a controversial but thought-provoking perspective, merging physics with philosophy.

Beyond Science: The Emotional and Philosophical Echo

The idea of multiple universes is not just a scientific theory—it is a mirror reflecting our deepest hopes and fears. It asks us to confront the possibility that our reality is not unique, that there might be other versions of ourselves living out different stories.

For some, this idea is exhilarating. It means that no decision is truly final, that every path exists somewhere. Every dream unrealized here might be fulfilled elsewhere. In another world, you might have chosen a different love, a different life, and lived it fully.

For others, the multiverse is disquieting. If there are infinite versions of everything, does that make this world, this moment, any less meaningful? Are we just one copy among endless variations?

Yet perhaps meaning arises precisely because this world feels real to us. Even if countless universes exist, the one we inhabit matters profoundly, because it is the one where we feel, love, create, and wonder.

The multiverse may expand our imagination, but it also deepens our sense of awe. It reminds us how precious it is to be aware—to exist at all in a cosmos that could contain endless possibilities.

The Limits of Knowledge

There is a haunting paradox at the heart of the multiverse idea. If other universes exist beyond our cosmic horizon, they may be forever inaccessible. We might never exchange light, energy, or information with them.

That raises a profound question: can we call something “real” if we can never observe it? Science traditionally deals with testable hypotheses, and the multiverse stretches that boundary to its breaking point.

Some physicists argue that even if we cannot see other universes directly, their existence may explain observable phenomena in our own—such as the fine-tuning of constants or patterns in cosmic background radiation. Others caution that the multiverse might lie beyond the scope of empirical science, belonging more to metaphysics than physics.

In truth, the frontier between science and philosophy has always been porous. Every great scientific revolution—from heliocentrism to quantum mechanics—began as a philosophical leap before evidence followed. The multiverse may be the next such leap.

Quantum Dreams and Consciousness

There is another, more mysterious frontier where the multiverse touches human experience: consciousness itself. Some interpretations of quantum mechanics suggest that the act of observation—the awareness of measurement—plays a role in determining outcomes.

If every quantum event spawns new realities, then consciousness may be entangled with the branching of universes. Each choice we make could send the cosmos down divergent paths, creating new worlds with every heartbeat.

This idea, though speculative, resonates deeply with our inner lives. It turns the multiverse from a distant abstraction into something intimate. The infinite may not only surround us—it may unfold through us.

Multiverse in Culture and Imagination

The notion of parallel worlds has captured human imagination for centuries, from ancient myths of mirrored realms to modern science fiction. Literature, film, and art explore the emotional and existential possibilities of other realities.

In these stories, parallel universes serve as mirrors of choice and destiny. They ask: who might we be if we had lived differently? What is the nature of identity in a world where infinite versions of us might exist?

From Borges’s “The Garden of Forking Paths” to modern films like Everything Everywhere All at Once, the multiverse has become both metaphor and science—a poetic language for exploring what it means to be human in an infinite cosmos.

A Universe of Universes

When we speak of the multiverse, we are not talking about something small or local. We are talking about the very architecture of reality itself. Each universe might have its own dimensions, its own physics, its own version of time.

Some might be lifeless voids; others could be teeming with unimaginable forms of life. Some might resemble ours so closely that you could mistake them for home; others might be governed by entirely alien principles.

If the multiverse exists, then the word “universe” itself becomes a misnomer. The totality of existence is not one cosmos, but a vast ocean of possibilities—a pluriverse, where every conceivable variation of reality exists somewhere.

The Search Continues

For now, the multiverse remains a theory—a grand, tantalizing possibility at the edge of our understanding. Yet scientists continue to search for clues: subtle imprints in cosmic radiation, patterns in gravitational waves, or mathematical bridges between quantum mechanics and cosmology.

As technology advances, we may find indirect evidence that points beyond our bubble of space and time. Or we may find that the multiverse, like the horizon, forever retreats as we approach it—a mystery we can approach but never fully grasp.

But even if we never confirm its existence, the idea of parallel universes has already changed us. It has expanded our imagination, humbled our assumptions, and reminded us that reality is far richer than our senses suggest.

The Poetry of Infinity

Perhaps the greatest gift of the multiverse idea is not scientific, but spiritual. It invites us to see existence as infinite in both scale and potential. It suggests that creation is not a single act, but an eternal process—one that births countless realities, each exploring different facets of what it means to be.

In this view, our universe is a poem within a vast cosmic anthology. Every world is a verse, every life a line, every moment a rhyme in the endless song of being.

Whether or not other universes exist, the very fact that we can imagine them reveals something profound about ourselves. The human mind, born of stardust, dares to dream of infinity—and in doing so, becomes infinite.

The Mystery That Defines Us

We may never step across the boundary between universes. We may never meet our other selves or witness worlds where physics takes strange and beautiful forms. Yet the question “Are there parallel universes beyond our own?” will continue to echo through science and philosophy alike, because it is ultimately a question about limits—of knowledge, of imagination, of existence itself.

The multiverse reminds us that reality might be far grander than our narrow experience allows. It humbles us, but it also exalts us, for we are the creatures who can ask such questions at all.

If other universes exist, then somewhere out there, infinite versions of us are asking the same question, gazing into their own night skies, feeling the same wonder.

And if they do not—if this universe is all there is—then it is enough. Because in our brief moment of awareness, we have touched the infinite.

We are, after all, the universe itself, dreaming of what lies beyond.