In the silent depths of space, stars live long and radiant lives. They are born from clouds of gas and dust, they shine for millions or billions of years, and they die in ways that are as spectacular as they are violent. Among all cosmic events, few rival the power, beauty, and mystery of a supernova—the explosive death of a star so immense that it can outshine entire galaxies for a brief, blazing moment.

A supernova is not just the death of a star. It is also a rebirth—a cosmic recycling of matter that forges the elements of planets, oceans, and life itself. Every atom of iron in your blood, every bit of gold in a wedding ring, every trace of calcium in your bones—all were born in the heart of a dying star. The story of a supernova, then, is also the story of us.

To understand what a supernova is, we must first understand the life of a star—how it burns, evolves, and ultimately collapses under its own weight.

The Life Before the Explosion

Every star begins as a whisper in a vast nebula—a cold cloud of hydrogen and helium drifting through the galaxy. Over time, gravity pulls the gas inward until pressure and heat at the center become so immense that hydrogen atoms fuse into helium. In that moment, a star is born.

For millions to billions of years, the star exists in a delicate balance. Gravity tries to crush it, but the nuclear fusion in its core pushes outward. This balance, known as hydrostatic equilibrium, keeps the star stable and glowing.

The more massive a star, the faster it burns its fuel. A star like our Sun will live for about 10 billion years. A star many times heavier than the Sun might live for only a few million. These colossal stars shine brilliantly but burn out quickly—cosmic titans destined for a dramatic death.

As a massive star exhausts its hydrogen fuel, fusion in its core ceases. The outward pressure fades, gravity gains the upper hand, and the core begins to collapse. But the star is not done fighting. The core becomes hot enough to ignite helium, fusing it into heavier elements like carbon and oxygen. This process continues in stages, with the star fusing successively heavier elements—neon, magnesium, silicon, sulfur—until finally, iron forms at its center.

Iron is the end of the line. Fusing iron consumes energy rather than releasing it. When a star’s core fills with iron, no further fusion can sustain it. The balance is broken, and the inevitable collapse begins.

The Cataclysmic Collapse

In the last moments of a massive star’s life, the drama unfolds on a scale that defies imagination. The core of the star—once thousands of kilometers across—collapses in less than a second to the size of a small city. Temperatures soar to over a hundred billion degrees, and the density becomes greater than an atomic nucleus.

As the core collapses, the outer layers of the star fall inward, slamming into the dense center and rebounding in a titanic shockwave. This shockwave blasts outward, tearing the star apart in one of the most powerful explosions in the universe—a core-collapse supernova.

For a brief period, the light from this explosion can rival that of an entire galaxy containing billions of stars. The energy released in that instant is so vast that it exceeds the total output of the Sun over its entire 10-billion-year lifetime.

The core left behind becomes either a neutron star—a city-sized object made entirely of neutrons—or, if the star was massive enough, a black hole, where gravity crushes all matter and even light into an infinitely dense point.

A Flash Across the Universe

When a supernova erupts, it sends waves of light and energy across the cosmos. For ancient civilizations, these sudden “new stars” appearing in the night sky were seen as omens, divine messages, or cosmic mysteries.

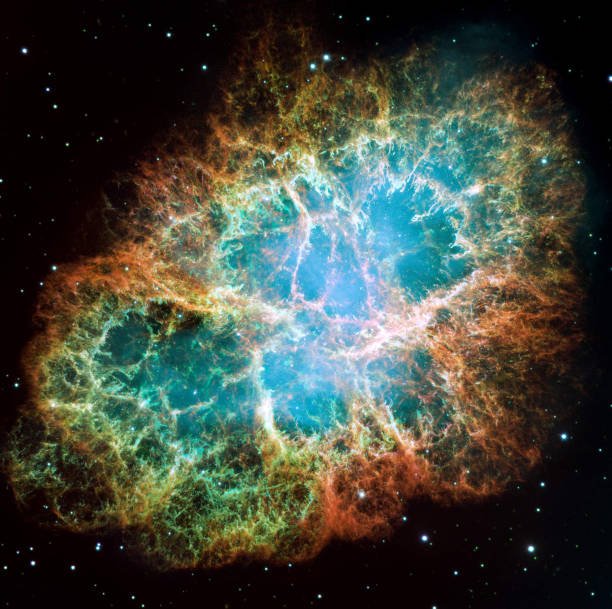

One of the most famous examples occurred in 1054 AD, when Chinese astronomers recorded a “guest star” bright enough to be visible in daylight for weeks. That explosion was the birth of the Crab Nebula, a cloud of expanding gas and dust still visible today through telescopes, glowing from the energy of the neutron star at its heart.

Supernovae are so bright that astronomers can use them to measure cosmic distances. Certain types—known as Type Ia supernovae—explode with consistent brightness, making them cosmic “standard candles.” By comparing their observed brightness to their known intrinsic luminosity, scientists can calculate how far away they are. This method was key to one of the greatest discoveries in modern cosmology: that the universe is expanding at an accelerating rate, driven by something mysterious we call dark energy.

The Two Great Paths to Explosion

Not all supernovae are born the same way. In fact, there are two main types, each telling a different story of cosmic destruction.

The first path is the core-collapse supernova, which occurs in massive stars—those at least eight times the mass of the Sun. As described earlier, these stars exhaust their nuclear fuel, collapse under their own gravity, and explode in a violent burst that leaves behind a neutron star or black hole.

The second path involves a more subtle cosmic partnership—a white dwarf in a binary system. When a Sun-like star dies, it sheds its outer layers and leaves behind a small, dense core called a white dwarf. This remnant is no longer undergoing fusion, but it still has gravity. If it orbits close to another star, it can steal material from its companion, slowly accumulating mass.

When the white dwarf grows too heavy—reaching about 1.4 times the Sun’s mass—it can no longer support itself. In an instant, runaway nuclear reactions ignite throughout the star, consuming it entirely in a Type Ia supernova. Unlike core-collapse explosions, these leave no remnant—just a cloud of glowing debris expanding into space.

These two paths—one from the death of massive stars, the other from the cannibalism of smaller ones—together create the fireworks that seed the universe with heavy elements.

The Forge of Elements

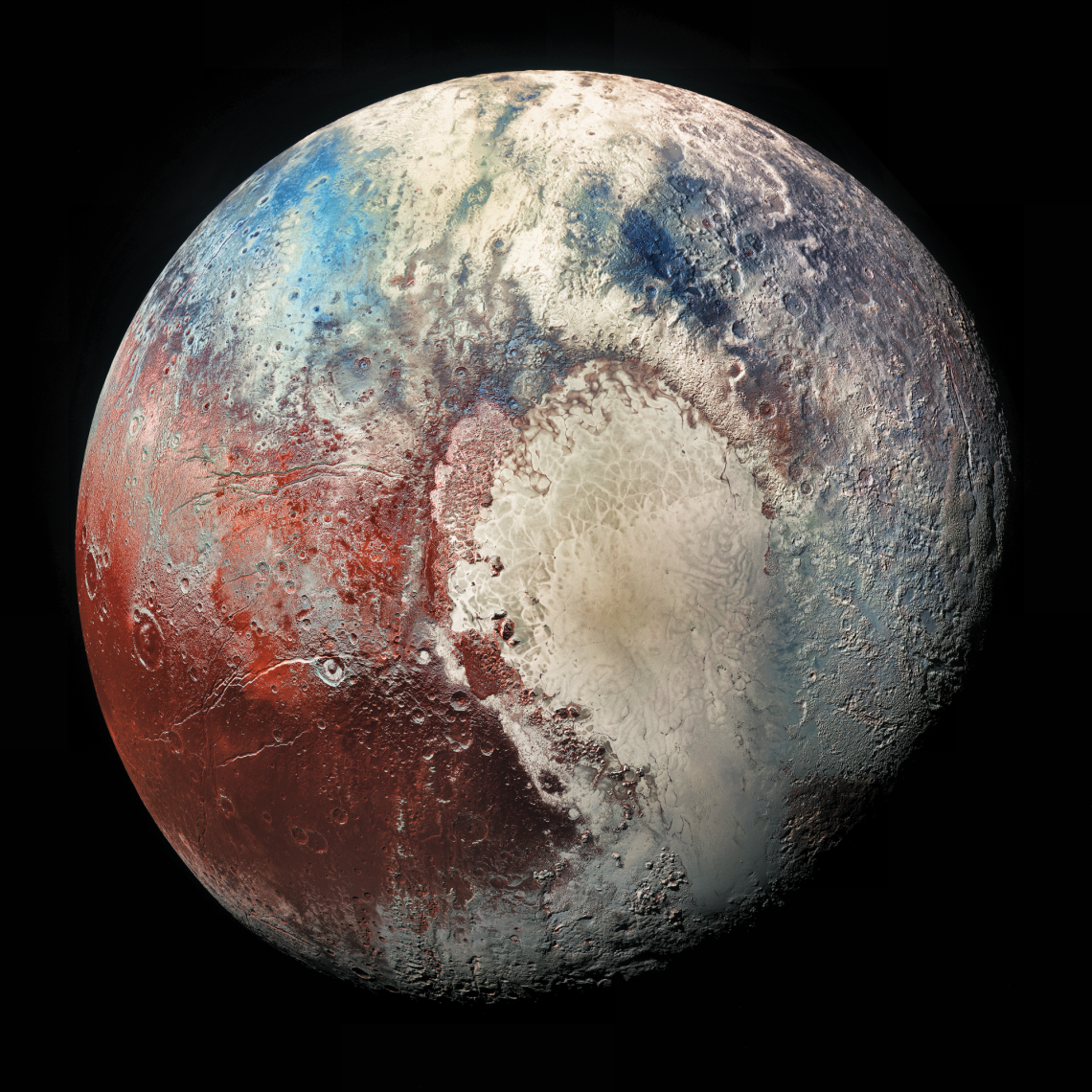

Perhaps the most profound truth about supernovae is that they are creators as much as destroyers. The tremendous heat and pressure of a supernova forge elements heavier than iron—gold, platinum, uranium, and others that could not form in normal stellar fusion.

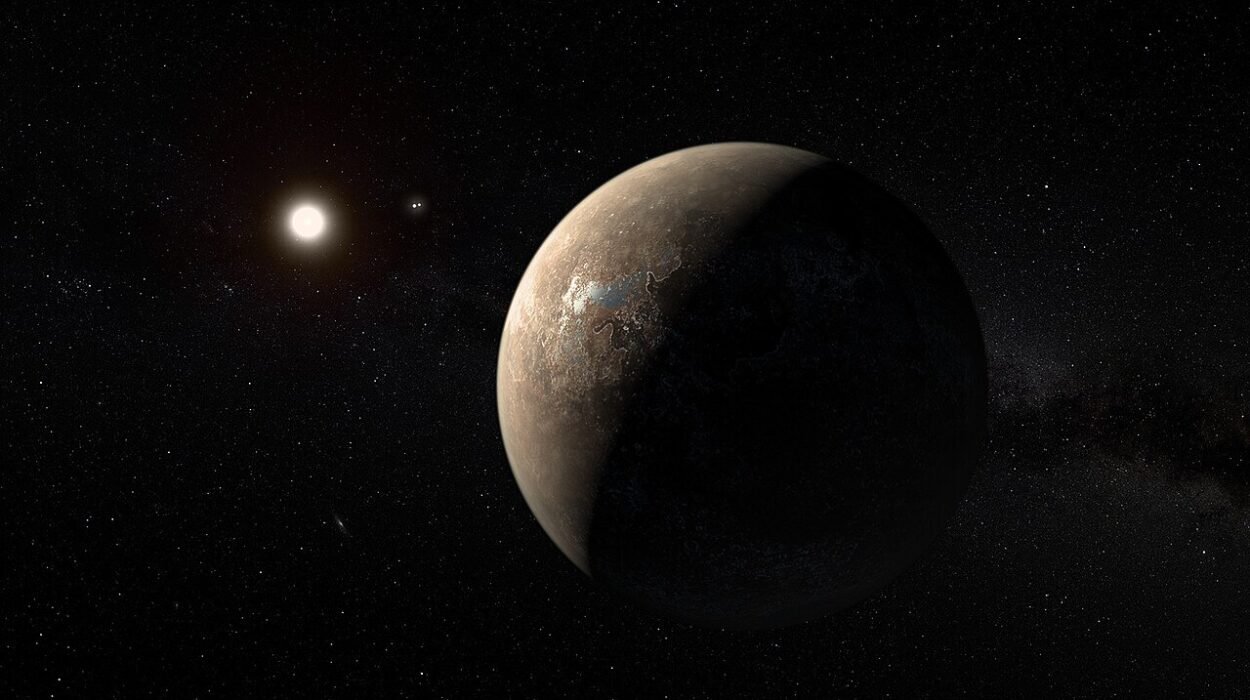

When a star explodes, it scatters these newly forged elements into space, enriching the interstellar medium. Future generations of stars and planets form from this enriched material. In this way, supernovae act as cosmic gardeners, spreading the seeds of chemistry throughout the galaxy.

Every molecule in your body carries the legacy of this stellar alchemy. The oxygen you breathe, the iron in your blood, the calcium in your bones—all were born in the nuclear furnace of a supernova billions of years ago. You are, quite literally, made of stardust.

The Remnants of a Cosmic Death

After the explosion fades, what remains is a hauntingly beautiful shell of gas and dust expanding outward into space. These supernova remnants glow with the light of shock waves colliding with interstellar material, producing intricate filaments and clouds of glowing color.

The Crab Nebula, Cassiopeia A, and the Vela Supernova Remnant are some of the most studied examples. Within these remnants, the physics of extreme conditions plays out—temperatures of millions of degrees, magnetic fields millions of times stronger than Earth’s, and particles accelerated to near-light speed.

In the heart of many remnants lies a neutron star—a stellar corpse of unimaginable density. A teaspoon of its material would weigh billions of tons. Some neutron stars spin rapidly and emit beams of radiation, becoming pulsars, cosmic lighthouses that flash across space with clocklike precision.

If the original star was massive enough, its core collapses beyond even the neutron stage, forming a black hole. These invisible remnants warp spacetime itself, pulling everything, even light, into their dark embrace.

Supernovae and the Cycle of Creation

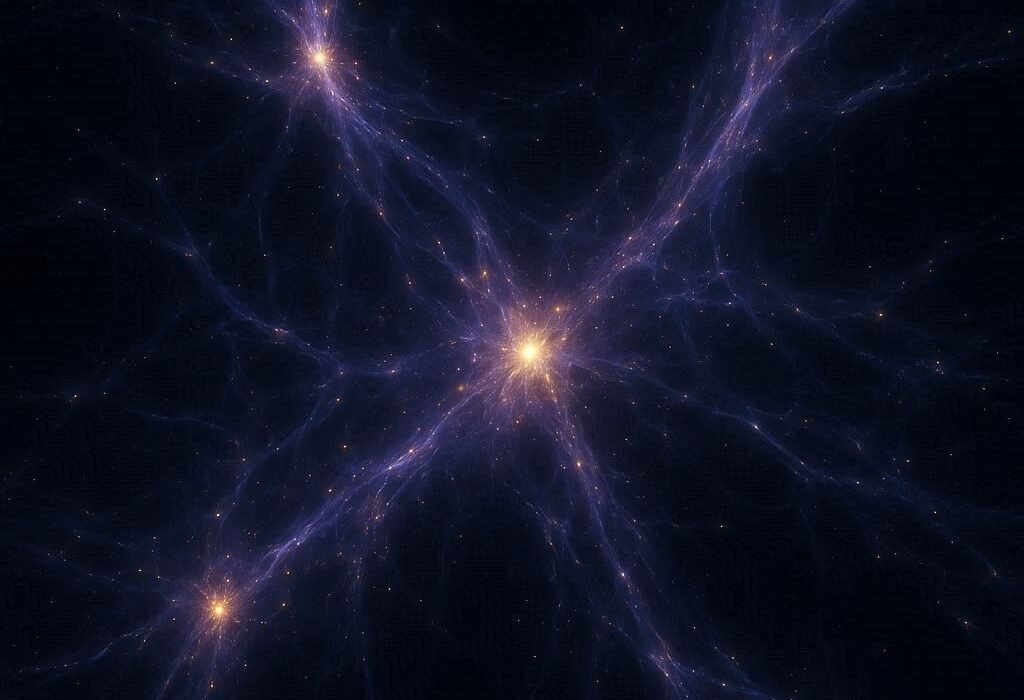

Though they mark an end, supernovae also mark beginnings. The shock waves from these explosions compress nearby clouds of gas and dust, triggering the birth of new stars. Thus, the death of one generation of stars gives rise to the next.

Galaxies are shaped and nourished by these events. Without supernovae, the universe would be sterile—a monotonous expanse of hydrogen and helium. It is through the explosions of stars that complexity, diversity, and life itself emerge.

In a very real sense, supernovae are the heartbeat of cosmic evolution. They regulate the chemistry of galaxies, drive the formation of planets, and even influence the conditions that make life possible.

When the Light Reaches Us

When the light of a supernova reaches Earth, it has traveled across millions, sometimes billions, of years. We witness not a current event, but a message from the distant past—a celestial postcard from a dying star.

In 1987, astronomers witnessed Supernova 1987A in the Large Magellanic Cloud, a nearby galaxy. It was the closest observed supernova in centuries and became a laboratory for modern astrophysics. Scientists detected not only the light from the explosion but also the burst of neutrinos—tiny, nearly massless particles that streamed out from the collapsing core. This was the first direct evidence that a collapsing star produces an immense flood of neutrinos, carrying away most of the energy.

The observation of Supernova 1987A confirmed many theories and opened new mysteries. Its light revealed rings of material surrounding the star, suggesting a turbulent history of mass loss before death. Even decades later, astronomers still watch its expanding remnant, studying how the debris interacts with the surrounding space.

Each new supernova we detect tells a slightly different story, adding to the cosmic narrative of creation and destruction.

The Role of Supernovae in Cosmic History

Supernovae have shaped the evolution of the universe from its earliest epochs. In the first billion years after the Big Bang, the very first stars—known as Population III stars—were massive and short-lived. When they exploded, they seeded the young cosmos with the first heavy elements, enabling the formation of rocky planets and complex chemistry.

Without those primordial supernovae, the universe would contain only hydrogen and helium. There would be no oxygen to breathe, no carbon for life, no silicon for rocks or computers. Every structure we see—from galaxies to living organisms—is a direct consequence of supernova explosions enriching the cosmic environment.

Even now, supernovae continue to sculpt galaxies. Their shock waves stir and mix interstellar gas, while their radiation and particles influence the birth rate of new stars. Some astronomers call this process feedback—a self-regulating system that keeps galaxies dynamic and alive.

The Human Connection to Cosmic Death

There is something profoundly emotional about supernovae. They remind us of the impermanence of all things, even stars. They reveal that destruction and creation are intertwined, that endings can give rise to beginnings.

When you look at the night sky, every twinkling star carries within it the promise of such a future. Some of the stars we see may already have exploded, but their light is still on its way to us. We are witnessing ghosts of the past, frozen in time by the finite speed of light.

In this way, supernovae are both a scientific phenomenon and a philosophical mirror. They remind us that we, too, are temporary flashes in a vast cosmic timeline. Yet just like the elements scattered by a dying star, our existence contributes to something greater—a continuation of the universe’s endless cycle of renewal.

The Search for the Next One

Astronomers today are constantly scanning the skies, waiting for the next nearby supernova. In our own galaxy, the Milky Way, such events occur roughly once every hundred years, though dust and distance often hide them from view.

The last visible one, Kepler’s Supernova, appeared in 1604 and was observed by Johannes Kepler himself. Since then, no naked-eye supernova has been seen within our galaxy, though remnants tell us they have occurred.

Many eyes now turn toward the red supergiant Betelgeuse in the constellation Orion. This massive star, nearing the end of its life, will one day explode as a supernova. When it does, it will be visible even in daylight, a celestial event that will echo across human history. It could happen tomorrow—or in 100,000 years. The uncertainty only adds to the anticipation.

Modern observatories like the Vera C. Rubin Observatory and the James Webb Space Telescope are poised to catch future supernovae in exquisite detail. They will allow scientists to study these explosions from their first moments, unlocking the physics of extreme matter and energy.

The Mathematics of Immortality

At the heart of every supernova lies an elegant balance of equations. They describe how gravity, pressure, and nuclear forces struggle and collapse, how matter transforms into radiation, and how energy flows through the cosmos.

From Einstein’s relativity to the equations of nuclear physics, these mathematical descriptions capture the soul of the event. They allow scientists to simulate supernovae on supercomputers, recreating their light curves, spectra, and remnants in breathtaking accuracy.

Yet even with all this knowledge, there remains a mystery—why do some stars explode in spectacular fashion while others collapse silently into black holes? What tiny variations in rotation, magnetic fields, or composition decide a star’s final fate? These are questions still being explored, questions that remind us how much there is left to learn.

Supernovae and the Future of Humanity

As humanity looks toward the stars, supernovae hold both danger and promise. A nearby explosion could flood Earth with radiation, stripping away our atmosphere or disrupting ecosystems. Thankfully, there are no known stars close enough to pose such a threat in the foreseeable future.

On the other hand, understanding supernovae may one day help us harness new forms of energy or guide interstellar exploration. The same principles that govern these stellar deaths—nuclear fusion, extreme pressure, and radiation—lie at the heart of the technologies we dream of mastering.

Moreover, by studying the light from distant supernovae, we can measure the expansion of the universe itself, tracing its history and ultimate fate. In this sense, supernovae are cosmic signposts pointing the way toward our understanding of eternity.

The Eternal Flame

Every supernova is both an end and a beginning—a heartbeat of the cosmos. When a star dies in fire, it sows the seeds for new suns, new worlds, and perhaps new forms of life. In its light, we see the beauty of impermanence, the grandeur of creation, and the intimate connection between the smallest atom and the grandest galaxy.

To witness a supernova is to glimpse the engine of the universe at work. It is to see death transformed into art, chaos into creation, silence into song. The universe is not static—it breathes, evolves, and renews itself through these fiery bursts of transformation.

You are living proof of that cosmic process. The atoms that form your body were once part of stars that died in supernovae billions of years ago. Their light and ashes became the building blocks of your world.

When you look up at the night sky and see a star twinkling, remember this: you are looking into the eyes of your ancestors—not human ancestors, but stellar ones. The universe lives through you, as you live because of it.

And someday, far in the future, when our own Sun fades and the Milky Way merges with Andromeda, new stars will be born from the remnants of old ones. The cycle will continue, endless and eternal.

The story of the supernova is the story of everything—the rise and fall, the birth and death, the light and darkness that together form the heartbeat of existence.

It is the universe’s way of saying that even in destruction, there is creation. Even in death, there is life. And in every explosion, there is the promise of something new waiting to be born.