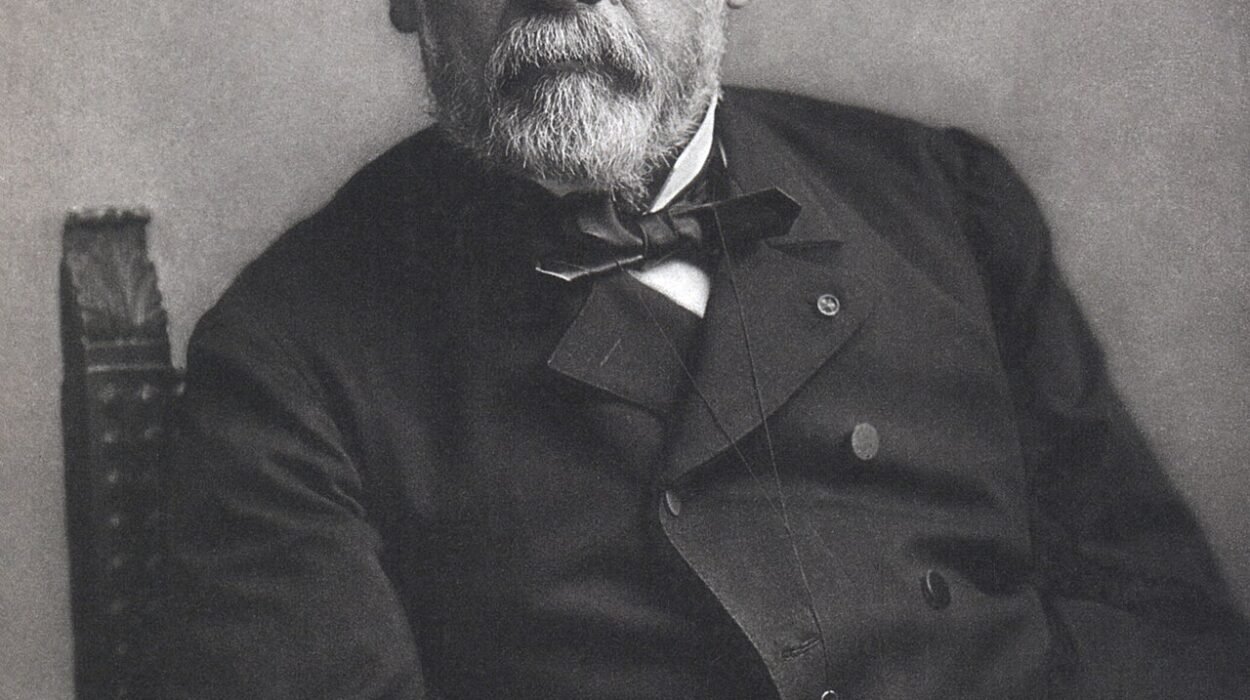

Sheikh Mujibur Rahman (1920–1975) was a prominent Bangladeshi political leader, often revered as the “Father of the Nation” for his pivotal role in the country’s independence. Born in Tungipara, then part of British India, Mujib was deeply involved in the struggle for political autonomy from an early age. As a leader of the Awami League, he championed the cause of Bengali nationalism and fought against the oppressive policies of West Pakistan. His leadership during the 1971 Liberation War was instrumental in the creation of Bangladesh as an independent nation. On March 7, 1971, his historic speech galvanized the Bengali people to seek independence, leading to the declaration of independence later that month. After Bangladesh gained independence, Mujib became the country’s first Prime Minister and later its President, working to rebuild the war-torn nation. His legacy as the founding leader of Bangladesh continues to influence the country’s politics and identity.

Early Life and Education

Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, often revered as the “Father of the Nation” in Bangladesh, was born on March 17, 1920, in the village of Tungipara, within the Gopalganj District, which was part of the British Raj at the time. His family belonged to a modestly well-off landowning Muslim community. Mujib was the third child among six siblings in the family of Sheikh Lutfur Rahman, a serestadar (court clerk) in the Gopalganj civil court, and Sayera Khatun, a homemaker. His early life was influenced by the rural, agrarian setting of Tungipara, which imbued in him a deep connection to the land and the common people.

Mujib’s education began at the local Gopalganj Public School, where he showed promise as a student, particularly in subjects like Bengali and English. However, his education was interrupted due to an eye operation at the age of fourteen, which caused him to miss several years of schooling. Despite this setback, Mujib was determined to continue his education, and he eventually completed his secondary education from the Gopalganj Missionary School in 1942. It was during this period that he developed a strong interest in politics, inspired by the anti-colonial movements that were gaining momentum across India.

After completing his secondary education, Mujib moved to Kolkata (then Calcutta) to pursue higher studies. He enrolled at the Islamia College (now Maulana Azad College), where he became actively involved in student politics. The early 1940s were a tumultuous time in the Indian subcontinent, marked by the Quit India Movement and the growing demand for Pakistan by the Muslim League. Mujib was deeply influenced by these events and became a member of the All India Muslim Students Federation, an organization aligned with the Muslim League. His involvement in student politics sharpened his leadership skills and introduced him to the larger political landscape of India.

In 1943, Sheikh Mujibur Rahman first met Huseyn Shaheed Suhrawardy, a prominent politician and the then Premier of Bengal, who would become a significant influence in his political career. Suhrawardy recognized Mujib’s potential and mentored him, helping to shape his early political ideology. Mujib’s activism grew during the Bengal Famine of 1943, a catastrophic event that claimed the lives of millions in Bengal. He organized relief efforts and became increasingly critical of British colonial policies that had exacerbated the famine. This experience deepened his commitment to the welfare of the common people and solidified his resolve to fight against oppression and injustice.

Mujib’s political activities during this period also brought him into contact with other leaders of the Muslim League, including Mohammad Ali Jinnah. However, Mujib’s views began to diverge from the League’s leadership, particularly on issues related to the rights and autonomy of Bengal. He was deeply concerned about the marginalization of Bengali Muslims within the broader Muslim League framework, which was increasingly dominated by leaders from West Pakistan. These early experiences laid the foundation for Mujib’s later advocacy for Bengali nationalism and autonomy.

In 1947, as the subcontinent was partitioned into India and Pakistan, Mujib returned to East Bengal, which became part of Pakistan. The partition was a momentous event, but it also sowed the seeds of future discord, as the new nation of Pakistan was divided into two geographically and culturally distinct regions—West Pakistan and East Pakistan (now Bangladesh). Despite their numerical majority, Bengalis in East Pakistan found themselves politically and economically marginalized by the ruling elite in West Pakistan.

Sheikh Mujibur Rahman continued his education at the University of Dhaka, where he studied law. However, his academic pursuits were soon overshadowed by his growing involvement in politics. In 1948, he was expelled from the university for leading protests demanding the recognition of Bengali as one of the state languages of Pakistan. This event marked the beginning of Mujib’s lifelong struggle for the rights of the Bengali people.

The early years of Mujib’s political career were marked by his dedication to the cause of Bengali language and culture. He became a key figure in the Language Movement of 1952, which sought to establish Bengali as an official language of Pakistan. The movement reached its peak on February 21, 1952, when police opened fire on peaceful protesters in Dhaka, killing several students. This event, known as the Language Martyrs’ Day, had a profound impact on Mujib and further strengthened his resolve to fight for the rights of Bengalis.

Mujib’s commitment to Bengali nationalism grew as he witnessed the increasing political and economic discrimination faced by the people of East Pakistan. He became a close associate of Suhrawardy, who had by then become a leading advocate for greater autonomy for East Pakistan within the Pakistani federation. Mujib’s political activities during this period led to multiple arrests and imprisonments, but these experiences only deepened his determination.

By the early 1950s, Mujib had emerged as a prominent leader within the Awami League, a political party founded by Suhrawardy and other leaders to represent the interests of East Pakistan. Mujib’s leadership within the Awami League was characterized by his ability to connect with the masses and articulate their aspirations. His vision of a secular, democratic, and inclusive Bengal resonated with a broad cross-section of the population, including students, workers, and peasants.

Political Awakening and Leadership in the Awami League

Sheikh Mujibur Rahman’s political awakening and subsequent rise to leadership in the Awami League were deeply intertwined with the socio-political dynamics of East Pakistan during the late 1940s and 1950s. As the newly formed state of Pakistan struggled to define its identity and governance structure, the disparity between East and West Pakistan became increasingly apparent. This period of political flux provided the backdrop for Mujib’s emergence as a key figure in the struggle for Bengali rights and autonomy.

In the late 1940s, following the partition of India and the creation of Pakistan, East Bengal (later East Pakistan) found itself politically subordinate to West Pakistan, despite its larger population. The central government in Karachi (the then-capital of Pakistan) was dominated by leaders from West Pakistan, who often disregarded the linguistic, cultural, and economic needs of the Bengali-speaking population in the east. This neglect was most acutely felt in the realm of language policy, where Urdu was promoted as the sole national language, sidelining Bengali, which was spoken by the majority in East Pakistan.

Mujib’s involvement in the Language Movement of 1952 marked his first major political engagement and set the stage for his future leadership. The movement was sparked by the Pakistani government’s refusal to grant Bengali equal status as a national language. As tensions escalated, Mujib became increasingly active in organizing protests and mobilizing public opinion. His role in the movement earned him recognition as a defender of Bengali culture and language, and he quickly became a prominent figure within the Awami League, which was at the forefront of the movement.

The Language Movement culminated in the tragic events of February 21, 1952, when police in Dhaka fired on unarmed protesters, killing several students. This day, now commemorated as International Mother Language Day, was a turning point in the struggle for Bengali rights. The deaths of the students galvanized public opinion and intensified demands for autonomy and recognition. Mujib’s involvement in the movement solidified his reputation as a committed leader who was willing to confront the central government on behalf of his people.

Following the Language Movement, Mujib’s political activities continued to focus on the broader issue of East Pakistan’s autonomy. He became an advocate for greater economic and political rights for Bengalis, who were increasingly marginalized under the central government’s policies. The economic disparity between East and West Pakistan was stark, with East Pakistan contributing the majority of the country’s export earnings through its jute production, yet receiving only a fraction of the benefits in terms of infrastructure development and public services.

In 1953, Sheikh Mujibur Rahman was elected as the General Secretary of the Awami League, a position that gave him greater influence within the party and allowed him to shape its agenda. Under the leadership of Huseyn Shaheed Suhrawardy and Maulana Abdul Hamid Khan Bhashani, the Awami League began to evolve into a powerful political force advocating for the rights of East Pakistan. Mujib’s role as General Secretary involved organizing grassroots support, particularly among students, laborers, and peasants, who were the backbone of the party’s constituency.

Mujib’s political philosophy during this period was heavily influenced by his belief in social justice, democracy, and nationalism. He was deeply concerned about the growing economic inequality between East and West Pakistan, as well as the lack of political representation for Bengalis in the central government. His speeches and writings from this time reflect a commitment to the idea of a secular and democratic state where the rights of all citizens, regardless of religion or ethnicity, would be protected.

The 1954 provincial elections in East Pakistan were a significant milestone in Mujib’s political career. The United Front, a coalition of parties including the Awami League, won a landslide victory, defeating the Muslim League, which was seen as representing the interests of West Pakistan. This victory was a clear mandate from the people of East Pakistan, demanding greater autonomy and recognition of their cultural and economic rights.

However, the victory was short-lived. The central government in West Pakistan, alarmed by the electoral success of the United Front and its demands for greater autonomy, dismissed the provincial government within two months and imposed direct rule. Mujib, along with other leaders of the United Front, was arrested. This event further fueled the growing resentment in East Pakistan and deepened the divide between the two wings of the country.

After his release from prison, Sheikh Mujibur Rahman continued to play a central role in East Pakistan’s struggle for autonomy. The dismissal of the United Front government and the subsequent imposition of martial law in Pakistan in 1958 by General Ayub Khan marked the beginning of a period of political repression. Ayub Khan’s regime was characterized by its attempts to suppress dissent and centralize power, which included the banning of political parties and the imposition of a highly centralized system of governance.

During this period, Mujib’s political activities were severely restricted. However, his commitment to the cause of Bengali nationalism remained undiminished. In the early 1960s, he began to reorganize the Awami League, which had been weakened by the political repression under Ayub Khan’s regime. Mujib focused on building a strong grassroots organization, reaching out to students, workers, and peasants, and articulating their demands for greater autonomy.

One of Mujib’s most significant contributions during this period was the articulation of the Six-Point Movement in 1966. The Six-Point Movement was a political and economic program that called for greater autonomy for East Pakistan. The six points were:

- A federal structure of government with a parliamentary system where the central government would have limited powers, focusing mainly on defense and foreign affairs.

- A separate currency for East Pakistan, or if there was a single currency, provisions to stop capital flight from East to West Pakistan.

- Control over taxation and revenue collection to rest with the provinces, ensuring that East Pakistan would have more control over its financial resources.

- The right of the provinces to maintain their own paramilitary forces.

- Control of trade, especially foreign trade, by the provinces, allowing East Pakistan to manage its own economic policies.

- A separate foreign exchange account for East Pakistan, ensuring that its foreign earnings would not be used disproportionately by West Pakistan.

The Six-Point Movement was a bold and radical departure from the existing structure of the Pakistani state. It was essentially a demand for a confederation, with East Pakistan having substantial autonomy. The movement resonated deeply with the people of East Pakistan, who saw it as a solution to their political and economic grievances.

Mujib’s leadership of the Six-Point Movement made him the undisputed leader of the Bengali nationalist movement. However, it also made him a target for the central government. In 1968, Mujib was arrested on charges of conspiracy against the state in what became known as the Agartala Conspiracy Case. The government accused Mujib and several others of conspiring with India to secede from Pakistan. The trial was widely seen as politically motivated, and it further inflamed tensions in East Pakistan.

The Agartala Conspiracy Case became a rallying point for the Bengali nationalist movement. Mass protests erupted across East Pakistan, demanding Mujib’s release. The trial turned Mujib into a symbol of resistance against the central government’s oppression. Under immense public pressure, the government eventually dropped the charges and released Mujib in 1969. His release was greeted with massive public celebrations, and he was bestowed with the title “Bangabandhu,” meaning “Friend of Bengal,” by the people.

Following his release, Mujib intensified his campaign for the Six-Point Movement. The political situation in Pakistan continued to deteriorate, with growing demands for autonomy in East Pakistan. In 1970, Pakistan held its first general elections, and the Awami League, under Mujib’s leadership, won a landslide victory in East Pakistan, securing 160 out of 162 seats allocated to the region in the National Assembly. This victory gave the Awami League an overall majority in the National Assembly, making Mujib the de facto leader of Pakistan.

However, the central government in West Pakistan, led by President Yahya Khan and supported by Zulfikar Ali Bhutto, the leader of the Pakistan People’s Party, refused to transfer power to Mujib. Negotiations between the two sides broke down, leading to a political deadlock. The refusal of the central government to recognize the democratic mandate of the people of East Pakistan set the stage for the subsequent conflict.

Mujib’s leadership during this period was characterized by his commitment to non-violence and his efforts to achieve a peaceful resolution to the crisis. However, as tensions escalated and the central government continued to resist the demands for autonomy, the situation in East Pakistan became increasingly volatile. In March 1971, after a series of failed negotiations, President Yahya Khan launched a military crackdown in East Pakistan, known as Operation Searchlight. The operation targeted political activists, students, and the general population, resulting in widespread atrocities.

In the face of this brutal crackdown, Mujib declared the independence of Bangladesh on March 26, 1971, just before being arrested and taken to West Pakistan. His declaration marked the beginning of the Bangladesh Liberation War, a nine-month-long conflict that would eventually lead to the creation of the independent state of Bangladesh. Mujib’s leadership during the liberation struggle, even in his absence, remained a source of inspiration for the people of Bangladesh.

The Road to Independence

The road to Bangladesh’s independence was a tumultuous and violent journey, marked by immense suffering and sacrifice. After Sheikh Mujibur Rahman’s declaration of independence on March 26, 1971, the people of East Pakistan, under the leadership of the Awami League, embarked on a full-scale struggle for liberation from the oppressive regime of West Pakistan. This section delves into the key events, strategies, and challenges that defined the road to independence for Bangladesh.

Following the declaration of independence, the Pakistani military launched a brutal crackdown on Dhaka and other major cities in East Pakistan as part of Operation Searchlight. The operation, which began on the night of March 25, 1971, was intended to crush the burgeoning independence movement. The military targeted students, intellectuals, and Awami League leaders, alongside widespread attacks on civilians. The scale of the atrocities was staggering, with estimates of those killed during the initial phase of the crackdown ranging into the thousands.

The immediate aftermath of the crackdown saw the emergence of the Mukti Bahini (Liberation Army), a guerrilla resistance force composed of Bengali military personnel, students, and civilians. The Mukti Bahini launched attacks on Pakistani military installations, communications, and supply lines, operating primarily in rural areas where they had the support of the local population. The guerrilla tactics employed by the Mukti Bahini were crucial in keeping the resistance alive, despite the overwhelming military superiority of the Pakistani forces.

As the conflict escalated, millions of refugees fled to neighboring India, seeking safety from the violence in East Pakistan. The refugee crisis put immense pressure on India, which had to contend with the influx of millions of people. India’s Prime Minister, Indira Gandhi, was initially reluctant to intervene directly in the conflict, but the scale of the humanitarian crisis, coupled with the growing international awareness of the atrocities being committed by the Pakistani military, eventually led India to take a more active role in the conflict.

In April 1971, the Provisional Government of Bangladesh, also known as the Mujibnagar Government, was formed in exile in India. The government was headed by Acting President Syed Nazrul Islam and Prime Minister Tajuddin Ahmad, with Sheikh Mujibur Rahman recognized as the President of Bangladesh, even though he was imprisoned in West Pakistan. The Mujibnagar Government served as the official representative of the Bangladeshi liberation movement and coordinated efforts to gain international recognition and support.

One of the key challenges faced by the Mujibnagar Government was securing international recognition for Bangladesh’s independence. The global response to the conflict was initially muted, with many countries hesitant to recognize the new state due to geopolitical concerns, including their relationships with Pakistan and its allies. However, as reports of the atrocities committed by the Pakistani military spread, international opinion began to shift. The role of the global media, particularly journalists who reported on the situation in East Pakistan, was crucial in raising awareness of the human rights violations taking place.

India’s decision to intervene militarily in the conflict was a turning point in the road to independence. In December 1971, after months of providing covert support to the Mukti Bahini, India formally entered the war following a series of border skirmishes with Pakistan and the bombing of Indian airfields by Pakistani forces. The Indo-Pakistani War of 1971, as it came to be known, saw the Indian military join forces with the Mukti Bahini in a coordinated campaign against the Pakistani military in East Pakistan.

The combined Indian and Mukti Bahini forces quickly gained the upper hand in the conflict. The Pakistani military, already stretched thin and demoralized by months of guerrilla warfare, was unable to effectively resist the coordinated offensive. The war culminated in the fall of Dhaka on December 16, 1971, when the Pakistani military, led by General A.A.K. Niazi, surrendered to the joint Indian-Bangladeshi forces. This surrender marked the end of the war and the official birth of the independent state of Bangladesh.

Sheikh Mujibur Rahman’s leadership during the Liberation War, even from imprisonment, was symbolic and crucial in rallying the Bengali people and garnering international support. His declaration of independence on March 26, 1971, was broadcast to the world, rallying the Bengali population and setting the stage for the international community to recognize the legitimacy of the struggle. Despite being imprisoned in West Pakistan, Mujib’s leadership remained a powerful source of inspiration for the resistance fighters and the civilian population enduring the war.

The victory of the joint Indian-Bangladeshi forces on December 16, 1971, was a moment of immense jubilation and relief for the people of Bangladesh. It marked not only the end of a brutal conflict but also the beginning of a new era for the nation. The unconditional surrender of the Pakistani military and the subsequent independence of Bangladesh were seen as the culmination of years of struggle and sacrifice.

In the wake of the war’s end, the newly independent Bangladesh faced the monumental task of rebuilding a war-torn country. The economic, social, and political infrastructure had been severely damaged by the conflict, and the challenges of establishing a functioning government and a stable economy were immense. The international community, recognizing the new nation’s struggles, began to extend aid and support, helping Bangladesh in its efforts to recover and rebuild.

Sheikh Mujibur Rahman returned to Dhaka in January 1972, having been released from imprisonment in West Pakistan. His return was met with overwhelming enthusiasm from the Bengali population, who saw him as the leader who had guided them through the struggle for independence. Mujib’s triumphant return marked the beginning of his leadership in the newly independent Bangladesh.

The newly formed government, with Mujib at its helm, focused on several key areas: consolidating national sovereignty, rebuilding the economy, and addressing the humanitarian needs of the population. Mujib’s government worked to establish a democratic framework, draft a new constitution, and lay the foundations for a functioning state. The constitution adopted in 1972 enshrined principles of democracy, secularism, and social justice, reflecting Mujib’s vision for Bangladesh.

Despite these efforts, the early years of Bangladesh’s independence were fraught with challenges. The country faced severe economic difficulties, including food shortages, infrastructure damage, and a lack of industrial development. Additionally, the political landscape was unstable, with various factions and political groups vying for influence. Mujib’s government had to navigate these complexities while striving to maintain national unity and promote economic development.

The challenges of leadership during this period were compounded by internal divisions and political unrest. While Mujib remained a popular and charismatic figure, his government faced criticism from various quarters for its handling of the country’s issues. The political atmosphere became increasingly polarized, with tensions between the ruling Awami League and opposition parties.

Liberation War and the Birth of Bangladesh

The Liberation War of 1971 was a defining period in the history of Bangladesh, marking the end of colonial oppression and the birth of a new nation. The conflict was characterized by intense struggles, both military and diplomatic, as the people of East Pakistan fought for their independence from West Pakistan. This section explores the key events, strategies, and diplomatic efforts that shaped the Liberation War and led to the establishment of Bangladesh.

The Liberation War was precipitated by the deep-seated grievances of the people of East Pakistan against the central government in West Pakistan. The denial of political representation, economic exploitation, and cultural marginalization were key issues that fueled the demand for independence. The political situation reached a boiling point in early 1971 when the central government in West Pakistan, led by President Yahya Khan, launched a brutal crackdown on the population in East Pakistan, aiming to quell the growing independence movement.

The military operation, known as Operation Searchlight, began on the night of March 25, 1971. The Pakistani military targeted Dhaka and other major cities, carrying out widespread atrocities against civilians. The operation aimed to suppress the independence movement by using force against political activists, students, and the general population. The scale of the violence was staggering, with reports of mass killings, rapes, and destruction of property.

In response to the crackdown, the Mukti Bahini (Liberation Army) was formed as a resistance force. Composed of Bengali military personnel, students, and civilians, the Mukti Bahini engaged in guerrilla warfare against the Pakistani military. The guerrilla tactics employed by the Mukti Bahini included hit-and-run attacks, sabotage of military supply lines, and disruption of communications. The resistance fighters operated primarily in rural areas, where they had the support of the local population.

The humanitarian crisis resulting from the conflict was severe. Millions of refugees fled to neighboring India to escape the violence, placing a significant burden on the Indian government. The influx of refugees, along with the reports of atrocities, drew international attention to the situation in East Pakistan. The global response to the crisis was initially slow, but as the scale of the violence became apparent, international pressure on the Pakistani government increased.

India’s role in the conflict became increasingly prominent as the war progressed. Prime Minister Indira Gandhi, initially cautious about direct intervention, was eventually compelled to act due to the growing humanitarian crisis and the threat posed by the conflict to regional stability. In December 1971, India formally entered the war following a series of border skirmishes with Pakistani forces and the bombing of Indian airfields by Pakistan.

The Indo-Pakistani War of 1971 was marked by a coordinated campaign by the Indian military and the Mukti Bahini against the Pakistani forces in East Pakistan. The combined forces made significant advances, capturing key cities and military installations. The Pakistani military, already stretched thin and demoralized, was unable to effectively resist the offensive. The war culminated in the fall of Dhaka on December 16, 1971, when Pakistani General A.A.K. Niazi surrendered to the joint Indian-Bangladeshi forces.

The surrender of the Pakistani military and the subsequent victory of the joint forces were momentous events in the history of Bangladesh. The liberation of Dhaka marked the end of the conflict and the beginning of a new era for the nation. The international community recognized Bangladesh’s independence, and the new country was admitted to the United Nations as a sovereign state.

The establishment of Bangladesh as an independent nation was a result of the immense sacrifices made by the Bengali people and their determination to achieve self-determination. The Liberation War was a struggle for justice, equality, and freedom, and the victory represented the realization of these aspirations.

In the aftermath of the war, the newly independent Bangladesh faced significant challenges in rebuilding and establishing a functional government. The country was left with extensive damage to its infrastructure, an economy in shambles, and a population in need of humanitarian assistance. The task of nation-building required both internal efforts and international support.

Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, who had been a central figure in the independence movement, returned to Bangladesh as the leader of the new nation. His leadership was crucial in navigating the complexities of post-war reconstruction and establishing the foundations of a democratic and inclusive state. Mujib’s vision for Bangladesh was centered on the principles of democracy, secularism, and social justice, reflecting the aspirations of the Bengali people.

Nation-Building and Challenges as Prime Minister

After the successful Liberation War and the establishment of Bangladesh as an independent nation in December 1971, Sheikh Mujibur Rahman faced the monumental task of rebuilding the country and addressing its myriad challenges. As the first Prime Minister of Bangladesh, Mujib’s leadership was pivotal in shaping the early years of the nation and laying the groundwork for its future.

The immediate post-war period was characterized by a sense of euphoria and relief among the population, but it was also marked by the harsh realities of rebuilding a war-torn country. Bangladesh faced extensive damage to its infrastructure, including roads, bridges, schools, and hospitals. The economic impact of the war was severe, with widespread disruptions to agriculture, industry, and trade. The new government had to address these pressing issues while also dealing with the humanitarian needs of the population.

One of Mujib’s first priorities as Prime Minister was to establish a functional government and restore order. He focused on drafting a new constitution for Bangladesh, which was adopted in 1972. The constitution enshrined principles of democracy, secularism, and social justice, reflecting Mujib’s vision for the country. It established a parliamentary system of government with a strong emphasis on the protection of fundamental rights and freedoms.

The new government faced several immediate challenges, including the need to provide relief and rehabilitation to war-affected communities. Mujib’s administration worked to address the urgent needs of displaced persons, provide medical care, and rebuild infrastructure. The government also sought international assistance to support its reconstruction efforts, and the international community responded with humanitarian aid and development assistance.

Economic development was another critical focus of Mujib’s government. The war had left Bangladesh with a devastated economy, and the government faced the challenge of restoring economic stability and promoting growth. Mujib’s administration initiated various economic reforms and development projects aimed at revitalizing key sectors such as agriculture, industry, and infrastructure.

One of the government’s significant initiatives was the emphasis on agricultural development, which was crucial given that the majority of the population depended on farming for their livelihood. The government introduced programs to increase agricultural productivity, provide support to farmers, and ensure food security. These efforts were aimed at achieving self-sufficiency in food production and reducing dependence on foreign aid.

In addition to agricultural reforms, Mujib’s government sought to develop the industrial sector to stimulate economic growth. The administration focused on rebuilding industries that had been damaged during the war and attracting foreign investment. Efforts were made to modernize infrastructure, including transportation and communication networks, to facilitate trade and economic activities.

Despite these efforts, the early years of Bangladesh’s independence were marked by significant challenges and difficulties. The country faced political instability, with internal divisions and tensions between various political factions. The Awami League, while dominant in the political landscape, faced criticism from opposition parties and segments of society dissatisfied with the government’s performance.

Economic hardships and governance issues also contributed to the challenges faced by Mujib’s administration. The country struggled with inflation, shortages of essential goods, and a lack of financial resources. The complexities of managing a newly independent nation with a damaged economy and infrastructure added to the difficulties faced by the government.

Mujib’s leadership was also tested by allegations of corruption and mismanagement within his administration. Critics accused the government of failing to effectively address the country’s economic problems and questioned the integrity of its policies. The political environment became increasingly polarized, with growing dissent and calls for reform.

In 1974, the government faced a severe crisis when the country experienced a devastating famine. The famine was caused by a combination of natural factors, including flooding and cyclones, and economic mismanagement. The crisis resulted in widespread suffering, with millions of people facing food shortages and starvation. The government’s response to the famine was criticized as inadequate, leading to further discontent and criticism of Mujib’s leadership.

The political situation continued to deteriorate as opposition parties and dissident groups mobilized against the government. In August 1975, Sheikh Mujibur Rahman and his family were tragically assassinated in a military coup. The coup marked a dramatic and tragic end to Mujib’s leadership and had profound consequences for Bangladesh.

The assassination of Sheikh Mujibur Rahman was a turning point in the history of Bangladesh. It led to a period of political instability and military rule, as the country grappled with the aftermath of the coup and the loss of its founding leader. Mujib’s legacy, however, endured as a symbol of the struggle for independence and the aspirations of the Bangladeshi people.

Assassination and Aftermath

On August 15, 1975, Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, the founding leader of Bangladesh and its first Prime Minister, was assassinated in a military coup. The political environment in Bangladesh had been increasingly unstable, characterized by economic difficulties, political unrest, and dissatisfaction with Mujib’s government. Amid this turmoil, a faction within the military orchestrated the coup.

The plotters, disenchanted with Mujib’s leadership, initiated their plan on the night of August 14, 1975. Early in the morning of August 15, they launched a well-coordinated attack on Mujib’s residence in Dhaka, known as Dhanmondi 32. The soldiers breached the security of the house with minimal resistance and took control of the premises. Sheikh Mujib, along with his wife, Sheikh Fazilatunnesa Mujib, and three of their children—Sheikh Kamal, Sheikh Jamal, and Sheikh Russel—were brutally murdered during the raid. Only Mujib’s two daughters, Sheikh Hasina and Sheikh Rehana, who were abroad at the time, survived the attack.

The military officers behind the coup justified their actions by accusing Mujib’s administration of corruption and inefficiency. They aimed to establish a new regime that they believed would better address the country’s problems. Following the coup, General Ziaur Rahman emerged as a prominent leader and took control of the government, marking the end of Mujib’s leadership and leading to a period of significant political and social upheaval.

The assassination shocked the nation and the international community. The brutal nature of the killings and the circumstances of the coup were met with widespread condemnation. The loss of Mujib, a central figure in the struggle for Bangladesh’s independence and early nation-building, was a severe blow to the country’s sense of stability and identity.

In the immediate aftermath, General Ziaur Rahman and the new regime began consolidating their power. The political landscape of Bangladesh shifted dramatically, leading to a period of military rule and ongoing instability. The new government implemented changes to the political and administrative structures, but the coup’s impact continued to resonate.

The assassination’s long-term effects were profound. Bangladesh experienced several changes in government and periods of political turbulence in the years following Mujib’s death. Despite the turmoil, Sheikh Mujibur Rahman’s legacy endured. His role in the independence movement and his vision for Bangladesh remained influential. His daughter, Sheikh Hasina, later returned to Bangladesh and became a prominent political leader, continuing many of the policies and ideals associated with Mujib.

The murder of Sheikh Mujibur Rahman remains a deeply traumatic event in Bangladesh’s history. Efforts to preserve his legacy include various memorials, museums, and public commemorations that honor his contributions to the country. His leadership and vision for a democratic and inclusive Bangladesh continue to be celebrated and remembered, reflecting his lasting impact on the nation.

Legacy and Impact

Sheikh Mujibur Rahman’s legacy is deeply intertwined with the history and identity of Bangladesh. As the central figure in the country’s struggle for independence and its early years as a sovereign nation, Mujib’s impact is felt across various aspects of Bangladeshi society and politics. This section explores his enduring legacy, the influence of his leadership, and the ways in which his vision has continued to shape the nation.

Mujib’s role in the struggle for independence has solidified his status as the “Father of the Nation” in Bangladesh. His leadership during the Liberation War, despite his imprisonment, and his pivotal role in the declaration of independence, are central to his legacy. The sacrifices made by Mujib and the people of Bangladesh during the war are commemorated annually on Independence Day, March 26, and in the celebrations surrounding Victory Day, December 16. These events honor the achievements of the liberation movement and reaffirm the values of freedom and self-determination that Mujib championed.

As the first Prime Minister of Bangladesh, Mujib’s vision for the country was grounded in principles of democracy, secularism, and social justice. His efforts to draft a new constitution and establish a democratic framework were foundational to the development of the Bangladeshi state. Although his administration faced significant challenges, including economic difficulties and political instability, Mujib’s commitment to building a democratic and inclusive society left a lasting imprint on the country’s political culture.

Mujib’s impact on Bangladeshi politics extends beyond his tenure as Prime Minister. His leadership style and political philosophy influenced subsequent generations of political leaders and activists. The Awami League, the party he led, remains a dominant political force in Bangladesh and continues to uphold many of the principles that Mujib espoused. His legacy is also reflected in the continued struggle for social justice, economic development, and democratic governance in the country.

In addition to his political legacy, Mujib’s contributions to the cultural and national identity of Bangladesh are significant. His speeches, writings, and public appearances have been preserved as important historical documents and sources of inspiration. The iconic image of Mujib, often depicted in statues, portraits, and commemorative events, symbolizes the spirit of the nation and the ideals for which he fought.

Mujib’s assassination in August 1975 marked a tragic end to his leadership and ushered in a period of political turmoil. However, his legacy endured through the continued efforts of his party, his family, and the people of Bangladesh. His daughter, Sheikh Hasina, has played a prominent role in Bangladeshi politics, serving as Prime Minister and continuing many of the policies and initiatives associated with Mujib’s vision.

In recent years, there has been a renewed focus on preserving and promoting the legacy of Sheikh Mujibur Rahman. Efforts to document his life and achievements, along with the establishment of museums and memorials dedicated to his memory, reflect the ongoing importance of his contributions to the nation. The celebration of his life and work serves as a reminder of the principles and values that guided his leadership and the enduring impact of his vision for Bangladesh.