For as long as humans have looked up at the night sky, we’ve wondered how to reach the stars. The distances between them are almost incomprehensible—light itself, the fastest thing in the universe, takes years, centuries, or even millennia to cross from one to another. Yet deep within the mathematics of general relativity lies a tantalizing possibility: perhaps there are hidden tunnels through the fabric of the cosmos, shortcuts that could link distant corners of the universe.

These hypothetical tunnels are called wormholes—bridges through spacetime that connect two separate regions of the universe, or perhaps even two entirely different universes. The idea sounds like science fiction, and in many ways it is. Yet, remarkably, the concept is rooted in the very real equations of physics.

To imagine a wormhole is to dream of traversing impossible distances in an instant, of stepping through a doorway in space and emerging among alien stars. But it’s also to confront some of the deepest mysteries of existence—what is space? What is time? And can the universe truly allow such miraculous connections to exist?

The Fabric of Spacetime

To understand wormholes, we must first understand the fabric they’re said to tunnel through: spacetime.

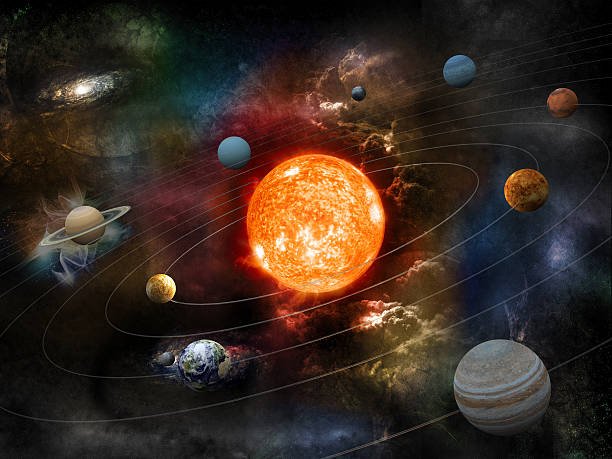

When Albert Einstein published his general theory of relativity in 1915, he redefined gravity not as a force, but as a geometric property of space and time. Massive objects like stars and planets curve spacetime around them, and that curvature tells other objects how to move. In essence, mass tells space how to curve, and curved space tells matter how to move.

If we could see spacetime as a flexible fabric, then a massive object would create a depression in it—like a bowling ball resting on a stretched rubber sheet. A smaller object rolling nearby would follow the curved path around the depression, just as the Moon orbits the Earth or the Earth orbits the Sun.

But if space can bend, twist, and curve under the influence of gravity, then perhaps, under the right conditions, it could fold in such a way that two distant points become connected. A wormhole, in this view, is like a tunnel bored through that fabric—a shortcut between otherwise distant parts of the universe.

The Einstein-Rosen Bridge

The first theoretical hint of wormholes emerged directly from Einstein’s equations themselves. In 1935, Einstein and his collaborator Nathan Rosen were studying the mathematical structure of black holes, those regions of spacetime where gravity becomes so intense that nothing, not even light, can escape.

They found that the equations describing a black hole solution could be extended to include not one, but two connected regions of spacetime. This connection, they realized, resembled a “bridge.” It linked one mouth (the entrance) in one part of the universe to another mouth in a different region, possibly even a different universe.

They called it the Einstein-Rosen bridge.

In essence, a black hole could be imagined as the entrance to a tunnel that leads elsewhere—perhaps to a white hole, a theoretical region that expels matter rather than swallowing it. Together, the black hole and white hole could form the two mouths of a wormhole, connected by a narrow throat.

At first glance, this seemed like a profound revelation—a mathematical doorway between distant realms. Yet there was a problem: Einstein-Rosen bridges, according to their own equations, were not traversable. The moment anything tried to cross, the tunnel would pinch shut too quickly for even light to make the journey. The bridge existed only in theory, an ephemeral connection that collapsed before it could be used.

The Shadow of Black Holes

To truly grasp wormholes, we must venture deeper into the strange world of black holes, where gravity and spacetime reach their most extreme expressions.

A black hole forms when a massive star exhausts its nuclear fuel and collapses under its own gravity. The inward pull becomes unstoppable, compressing the star’s mass into an infinitesimally small point—a singularity—where the laws of physics as we know them break down. Around this singularity forms an invisible boundary called the event horizon, beyond which nothing can return.

Inside a black hole, all paths lead inward. Yet mathematically, solutions to Einstein’s equations suggest that there might be other ways to connect regions of spacetime around these singularities. It is from such extreme geometries that the idea of wormholes arises.

Black holes and wormholes are cousins in the geometry of the cosmos—both bend spacetime to its limits. But while black holes trap everything, wormholes promise escape. One represents the ultimate prison; the other, the ultimate passage.

The Birth of the Traversable Wormhole

In the mid-20th century, physicists began to wonder whether wormholes might be made stable—or even traversable. Could there be a way for a spacecraft, or perhaps even a person, to pass safely through such a tunnel?

In 1955, John Wheeler, one of the great theoretical physicists of the 20th century, coined the term “wormhole.” He imagined spacetime as a kind of quantum foam—an ever-shifting sea of tiny, fluctuating geometries at the smallest scales. Within this foam, minute wormholes might constantly appear and disappear, microscopic tunnels flickering in and out of existence.

But it was not until the late 1980s that physicists Kip Thorne and Michael Morris seriously investigated the possibility of a traversable wormhole—a tunnel that could remain open long enough for a traveler to pass through.

Their research, famously inspired by science fiction writer Carl Sagan’s novel Contact, revealed something astonishing: such a wormhole could, in principle, exist within the framework of general relativity—but it would require a form of matter unlike anything we’ve ever seen.

This matter, they discovered, would need to have negative energy density—it would have to push outward rather than pull inward, counteracting the natural tendency of gravity to make the wormhole collapse. Ordinary matter, with its positive energy, cannot do this. Only exotic matter, with negative energy, could keep the wormhole throat open.

The Role of Exotic Matter

The idea of exotic matter may sound fantastical, but it’s not pure invention. Quantum physics allows for regions of space where the energy density can temporarily dip below zero—this happens, for instance, in the Casimir effect, where two uncharged plates in a vacuum experience an attractive force due to quantum fluctuations.

In this strange quantum world, particles and antiparticles constantly pop in and out of existence, borrowing energy from the vacuum in fleeting moments. These fluctuations suggest that negative energy can exist, though only in tiny amounts and for very short times.

To build a stable, human-sized wormhole, we would need vast quantities of such negative energy—something far beyond our technological or theoretical grasp. Yet the concept is tantalizing, because it bridges the two great pillars of modern physics: general relativity, which governs the large-scale structure of the universe, and quantum mechanics, which rules the subatomic realm.

If wormholes do exist, their stability may depend on the delicate interplay between these two domains—a clue, perhaps, to the long-sought unification of physics.

Wormholes and Time Travel

The most astonishing implication of traversable wormholes is not merely travel across space—but travel across time.

Einstein’s equations link space and time into a single entity: spacetime. If a wormhole connects two points in space, it might also connect two moments in time. By manipulating the wormhole’s geometry—say, by moving one mouth at relativistic speeds or placing it in a strong gravitational field—it’s theoretically possible for time to pass differently at each end.

Imagine one mouth of a wormhole remaining near Earth, while the other is accelerated close to the speed of light and then brought back. Because of time dilation (a consequence of Einstein’s relativity), the traveling mouth would have aged less than the stationary one. Step through the wormhole, and you might emerge in your own past—or far into the future.

In effect, a wormhole could become a time machine.

This idea, while exhilarating, also raises profound paradoxes. What happens if someone travels back in time and prevents their own journey? Do alternate timelines branch off, or does the universe somehow forbid such contradictions?

Stephen Hawking famously proposed the Chronology Protection Conjecture, suggesting that the laws of physics prevent time loops from forming—perhaps through quantum instabilities that destroy the wormhole before it can be used for time travel. In other words, nature may have a built-in safeguard to keep causality intact.

The Geometry of the Impossible

Wormholes stretch not just the imagination, but also the geometry of space itself. To visualize one, imagine taking a sheet of paper and drawing two dots on it. The straight-line distance between them represents ordinary space. Now fold the paper so the two dots touch—if you poke a hole through at the meeting point, you’ve created a shortcut between them.

That shortcut is a wormhole.

In spacetime, however, we’re not dealing with two-dimensional paper but with a four-dimensional continuum. A wormhole would exist as a kind of tunnel in this higher-dimensional structure—a hyperspatial conduit connecting two regions that might otherwise be light-years apart.

The “mouths” of the wormhole are the entry and exit points, while the “throat” is the narrow region in between. Depending on its shape and curvature, the throat might stretch, twist, or even branch into multiple paths. Some theoretical solutions suggest that wormholes could connect not just distant points in our universe, but entirely different universes in a multiverse scenario.

If so, every wormhole could be a gateway not merely through space or time, but between realities themselves.

Wormholes and Quantum Entanglement

In recent years, a fascinating idea has emerged in theoretical physics: that wormholes and quantum entanglement might be two sides of the same coin.

Entanglement is one of the strangest features of quantum mechanics. When two particles become entangled, their states remain correlated no matter how far apart they are. Measure one, and you instantly affect the other, even across vast distances. Einstein derisively called this “spooky action at a distance,” though it has since been confirmed in countless experiments.

In 2013, physicists Juan Maldacena and Leonard Susskind proposed a radical idea known as ER = EPR. The “ER” stands for Einstein-Rosen bridges (wormholes), and “EPR” refers to the Einstein-Podolsky-Rosen paradox about entanglement. Their conjecture suggests that every pair of entangled particles is connected by a microscopic wormhole—so small and fleeting that it cannot be used for communication or travel, but nevertheless real in a geometric sense.

If true, this means spacetime itself could be woven from the threads of quantum entanglement—that the geometry of the universe arises from the very structure of quantum connections. In this view, wormholes aren’t exotic exceptions; they are fundamental features of the universe’s fabric.

The Search for Evidence

Despite decades of speculation, no observational evidence of wormholes has yet been found. Their hypothetical nature makes them difficult to detect, but scientists continue to explore possible signatures they might leave behind.

If a wormhole existed near a massive object, its gravitational effects could mimic or subtly differ from those of a black hole. Light passing near a wormhole might be distorted in unique ways, creating unusual gravitational lensing patterns. Some researchers even suggest that certain mysterious astronomical phenomena—like repeating fast radio bursts or unusual quasars—could hint at wormhole activity, though no conclusive proof exists.

The upcoming generations of telescopes and gravitational-wave detectors may help. The Event Horizon Telescope, which captured the first image of a black hole’s shadow, could one day reveal whether similar shadows conceal something stranger—a wormhole throat rather than a singularity.

If such evidence were ever found, it would revolutionize our understanding of space, time, and the cosmos itself.

The Energy Cost of Crossing the Universe

Even if wormholes exist, using them would be no small feat. The energy required to stabilize and enlarge a wormhole throat could exceed the mass-energy of entire stars. The exotic matter necessary might need to be generated or harvested in ways far beyond our current abilities.

Moreover, traversing a wormhole could expose travelers to intense tidal forces, radiation, and quantum fluctuations. The throat of the wormhole might need to be perfectly engineered to avoid catastrophic collapse. The slightest instability could cause the tunnel to pinch off, trapping or annihilating anything inside.

In essence, the challenge is not just to find a wormhole, but to make one traversable, stable, and survivable—a task that lies far beyond even our most advanced physics and engineering.

The Legacy in Imagination and Art

Though wormholes remain theoretical, they’ve captured the human imagination like few other concepts. From the shimmering portals of Interstellar to the dimensional gateways of Stargate and Doctor Who, they embody our longing to transcend the limits of space and time.

Carl Sagan’s Contact presented one of the most scientifically grounded depictions, thanks to Kip Thorne’s direct input, portraying wormholes not as magic but as the natural outgrowth of Einstein’s universe. These stories resonate because they express a deep truth: that humans are explorers by nature, forever seeking pathways into the unknown.

Wormholes, whether real or imagined, are symbols of that restless curiosity. They represent the possibility that the universe might hold hidden doors, waiting for us to find the keys.

The Edge of Knowledge

At the frontier of modern physics, wormholes occupy a liminal space between the known and the speculative. They are mathematical possibilities, not proven realities—but their study continues to push science forward.

To understand whether wormholes can exist, physicists must grapple with the unification of quantum mechanics and general relativity—a challenge that could ultimately reveal the true nature of spacetime itself.

In this way, wormholes are not just theoretical constructs; they are signposts pointing toward a deeper truth. They force us to ask whether reality is continuous or discrete, whether information can be destroyed or only transformed, whether the cosmos has limits—or infinite doorways hidden in plain sight.

The Philosophy of Passage

Beyond their physics, wormholes touch something profoundly human. They are metaphors for our desire to connect—across distance, across time, across the boundaries of understanding. They remind us that even in the vast emptiness between stars, the mind dares to imagine bridges.

In every wormhole equation lies a reflection of our own yearning: the wish to overcome separation, to reunite what distance has divided. In that sense, the search for wormholes is not just about faster travel—it’s about transcending isolation, about finding unity in a fragmented universe.

When Einstein wrote that imagination is more important than knowledge, he could have been speaking directly to the idea of wormholes. They exist, for now, in the realm of imagination—but it is imagination that leads science forward, transforming dreams into discoveries.

The Infinite Horizon

Perhaps someday, far in the future, when humanity has learned to master the energies of the stars and the fabric of spacetime itself, a traveler will step through a wormhole. Perhaps they’ll emerge beneath a new sun, on a distant world, and look back through the portal at the blue glow of Earth.

In that moment, the ancient dream of crossing the cosmos will be fulfilled—not by breaking the laws of physics, but by embracing their deepest possibilities.

Until that day, wormholes remain the poetry of the universe—a reminder that even the most impossible journeys begin in the mind. They are the echo of a truth we have always felt: that space is not a barrier, but a canvas, and that the universe, vast and mysterious, may yet reveal paths beyond imagination.

Wormholes are more than tunnels through spacetime—they are the embodiment of humanity’s eternal quest to bridge the impossible, to reach beyond what is known, and to find, in the darkness between stars, the hidden doors of the cosmos itself.