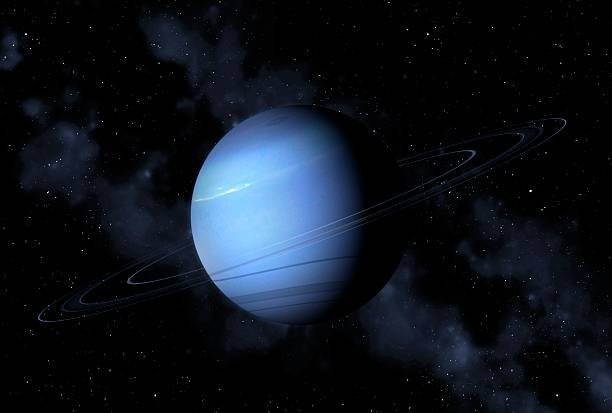

Far beyond the warmth of the Sun, where light fades into twilight and the solar wind slows to a whisper, there drifts a world of astonishing beauty and violence. Neptune—the eighth and farthest known planet from the Sun—is a mysterious, majestic giant wrapped in deep blue storms and roaring winds faster than any on Earth. To gaze upon it is to look into the heart of the unknown.

From over 4.5 billion kilometers away, Neptune glows like a sapphire in the cosmic sea, its color the result of sunlight scattered through its frigid atmosphere of hydrogen, helium, and methane. To the naked eye, it appears serene, calm, and distant—but beneath that calm lies a world of unimaginable ferocity. Winds race across the planet at supersonic speeds, massive dark storms rise and vanish without warning, and the deep interior remains hidden beneath layers of ice and gas that defy comprehension.

Neptune is a world of contradictions. It is both peaceful and violent, silent and thunderous, frozen and boiling with energy. It is the last planet in the Solar System, a sentinel on the edge of darkness, and a reminder that beauty often hides power.

Discovery in the Shadows

Unlike all other planets visible to ancient astronomers, Neptune was not discovered by sight. It was discovered by mathematics—by human reason reaching farther than human eyes could see.

After the discovery of Uranus in 1781 by William Herschel, astronomers noticed something strange. Uranus did not move exactly as Newton’s laws predicted. It seemed to wobble and stray, as if tugged by an unseen companion. Two mathematicians, working independently—John Couch Adams in England and Urbain Le Verrier in France—calculated where such a planet must be to cause Uranus’s deviations.

Their calculations pointed to a patch of sky in the constellation Aquarius. In 1846, Johann Galle of the Berlin Observatory turned his telescope there—and within one degree of Le Verrier’s prediction, he found Neptune.

It was a triumph of human intellect, proof that mathematics could uncover worlds before eyes ever saw them. Neptune became the first planet discovered through the power of calculation alone—a symbol of the precision and beauty of celestial mechanics.

The Cold Frontier

Neptune lies at an average distance of about 4.5 billion kilometers from the Sun—30 times farther than Earth. At such a distance, sunlight is only one nine-hundredth as strong as it is on Earth. The planet receives so little warmth that its upper atmosphere sits at a frigid −214°C.

Yet despite this bitter cold, Neptune radiates more than twice as much energy as it receives from the Sun. Something deep within the planet burns with invisible heat—perhaps the slow contraction of its core, or the remnants of formation energy trapped since the dawn of the Solar System.

This internal heat gives Neptune its restless nature. It drives its immense winds and monstrous storms, fueling a churning atmosphere unlike any other. The contrast between its distant, frozen environment and its dynamic weather makes Neptune one of the most paradoxical worlds ever studied—a cold planet of incredible motion.

The Azure Beauty of Methane Skies

When spacecraft and telescopes look at Neptune, the first thing they see is its mesmerizing blue color. This hue, more intense than that of its neighbor Uranus, comes from methane gas in the upper atmosphere. Methane absorbs red light but reflects blue, creating a tone that evokes calm oceans and distant horizons.

But Neptune’s blue is not just methane. Observations suggest that something else—perhaps unknown aerosols or haze particles—enhances the richness of its color, giving it that deep sapphire glow. Scientists have compared the visual experience to gazing through a window of tranquility into a storm of unimaginable power.

Beneath the upper layers of atmosphere, Neptune’s composition is roughly 80% hydrogen, 19% helium, and 1% methane, with traces of water, ammonia, and other compounds. As we descend deeper, the pressure rises and the gases compress into exotic states—liquid, supercritical, and possibly even metallic. Somewhere far below the visible clouds lies an ocean of hot, dense water and ammonia, thousands of kilometers deep, surrounding a rocky core.

It is a world where chemistry and physics dance at the edge of the possible.

The Realm of Supersonic Winds

If there is one defining feature of Neptune’s atmosphere, it is wind. The planet’s storms move faster than any other in the Solar System—winds roaring at more than 2,100 kilometers per hour, faster than the speed of sound on Earth. These winds whip across the planet’s atmosphere, shaping vast bands of clouds and massive vortices that appear and vanish in months.

How can such a distant, cold world generate such ferocity? Scientists believe that Neptune’s internal heat plays a key role. While Uranus, similar in size and composition, is oddly still, Neptune’s interior seems alive with convection—hot material rising, cool material sinking, driving massive circulation patterns in the atmosphere.

The result is chaos on a planetary scale. At the equator, winds blow westward at tremendous speeds, while near the poles, they reverse direction, creating immense shear zones where storms form. White methane clouds streak across the atmosphere like wisps of frost in a hurricane.

This endless motion makes Neptune a living storm—a world where the wind never stops.

The Great Dark Spot: A Storm Larger Than Earth

When Voyager 2 flew past Neptune in 1989—the only spacecraft ever to visit—it captured images that astonished scientists. Among the planet’s swirling blue bands was a vast, dark oval the size of Earth itself. It was the Great Dark Spot, a storm so immense that it could swallow continents whole.

Like Jupiter’s Great Red Spot, this was a high-pressure system, an anticyclone spinning in the upper atmosphere. But unlike Jupiter’s centuries-old storm, Neptune’s was transient. When the Hubble Space Telescope looked again a few years later, the Great Dark Spot had vanished—only to be replaced by new dark ovals forming elsewhere.

This impermanence reveals the dynamic nature of Neptune’s weather. Storms rise, rage, and die within years, reshaped by the planet’s restless winds. The Great Dark Spot was accompanied by a bright companion cloud, nicknamed the “Scooter,” racing around the planet every 16 hours—a reminder of the constant, unseen turbulence beneath the serene blue facade.

Today, telescopes continue to spot new dark spots forming and dissipating. Each one is a mystery—an echo of the planet’s internal energy bursting through the clouds.

The Invisible Ocean of Ice and Fire

Beneath Neptune’s atmosphere lies a realm unlike anything on Earth. Here, under pressures millions of times greater than our atmosphere and temperatures thousands of degrees hot, hydrogen and oxygen molecules combine into exotic materials.

Scientists believe Neptune hides a vast “mantle” of water, ammonia, and methane in supercritical form—neither gas nor liquid, but something in between. This layer behaves like an ocean, though calling it water would be misleading; it is a dense, hot, electrically conductive fluid capable of generating magnetic fields and heat.

Deeper still, at the planet’s center, lies a rocky core perhaps ten times the mass of Earth. This core, compressed by unimaginable gravity, may reach temperatures around 7,000°C—hotter than the surface of the Sun. It is this heat that seeps upward, driving the winds and storms of Neptune’s visible atmosphere.

In recent years, scientists have speculated about the formation of “diamond rain” within this deep interior. Under extreme pressure, methane may break apart, and carbon atoms could crystallize into diamonds, falling like glittering stones through the depths. In Neptune’s eternal twilight, it might quite literally rain diamonds—a surreal beauty forged by crushing physics.

The Magnetic Field from Another World

Neptune’s magnetic field is as strange as its storms. Unlike Earth’s neatly aligned dipole, Neptune’s field is tilted by about 47 degrees from its rotation axis and offset from the planet’s center by thousands of kilometers. This means that its magnetic poles are not opposite each other and wander unpredictably.

The cause of this oddity likely lies in the planet’s unique structure. Instead of a solid core generating magnetism, Neptune’s magnetic field probably arises from fluid motions in its electrically conductive mantle of water and ammonia. These turbulent flows produce a lopsided magnetic field that twists and wobbles as the planet rotates.

As Voyager 2 passed Neptune, it recorded dramatic variations in the magnetic field, showing that it flickers like a heartbeat—a magnetic pulse from a deep, unseen ocean. This complexity gives scientists clues about how planetary magnetic fields form, and why gas and ice giants differ so greatly from rocky planets like Earth.

The Dance of Moons and Rings

Orbiting this windy blue world are 14 known moons and a faint system of dusty rings. The moons vary from tiny captured asteroids to the enormous and enigmatic Triton—the crown jewel of Neptune’s system.

The rings, first suspected in the 1980s and later confirmed by Voyager 2, are composed of dark, icy particles mixed with dust. They are faint and incomplete, forming arcs rather than continuous circles—a mystery that still puzzles scientists. These arcs may be gravitationally stabilized by nearby moons, preventing them from dispersing into full rings.

But the true wonder of Neptune’s realm is Triton.

Triton: The Captured World

Triton, Neptune’s largest moon, is unlike any other in the Solar System. It orbits the planet backward—retrograde—suggesting it was not born there, but captured long ago. Most likely, Triton was once a dwarf planet in the Kuiper Belt, similar to Pluto, until Neptune’s gravity snared it eons ago.

Triton is a world of frozen nitrogen, methane, and water ice. Its surface is sculpted by cryovolcanoes—geysers that erupt with nitrogen gas instead of molten rock. These eruptions suggest that Triton is geologically active, powered by tidal forces and internal heat.

Voyager 2’s images revealed a landscape of smooth plains, ridges, and strange “cantaloupe terrain,” unlike anything else in the Solar System. At −235°C, it is one of the coldest places known, yet paradoxically alive with motion.

Triton’s capture likely destabilized Neptune’s original moons, scattering them and reshaping the system. It is both a fossil of the early Solar System and a living example of how gravity sculpts destiny.

In the distant future, Triton will spiral closer to Neptune and eventually be torn apart, forming a magnificent new ring system. Even in death, it will transform beauty into another form.

Voyager 2: Humanity’s Glimpse into the Blue Unknown

Only one spacecraft has ever visited Neptune: NASA’s Voyager 2, which flew by in August 1989 after a 12-year journey through the outer Solar System. The encounter lasted just a few hours, yet it revealed an entire world.

Voyager 2 discovered the Great Dark Spot, measured the planet’s winds, mapped its rings, and unveiled Triton’s icy wonders. It found lightning in the atmosphere, detected a magnetic field tilted and twisted beyond expectation, and captured the most haunting images of the blue planet ever seen.

After passing Neptune, Voyager 2 continued into the depths of interstellar space, carrying humanity’s message engraved on its golden record. Its visit to Neptune remains one of our species’ greatest achievements—a moment when we reached the edge of sunlight and looked into the deep blue heart of the unknown.

The Enigma of Internal Heat

One of Neptune’s greatest mysteries is its internal heat. Despite being far from the Sun and receiving little radiation, Neptune emits more than twice the energy it absorbs. In contrast, its near-twin Uranus radiates almost no extra heat at all.

Why is Neptune so warm inside? Several theories exist. Perhaps its formation trapped more heat, or its core releases gravitational energy as it slowly contracts. Another idea suggests that methane deep within separates into carbon and hydrogen, releasing latent heat and forming diamond rain that warms the planet from within.

Whatever the cause, this heat is the lifeblood of Neptune’s storms. It rises from the depths, fueling the turbulence that shapes the planet’s ever-changing face. Neptune’s invisible fire is what makes its outer cold so alive.

The Rhythm of the Blue Giant

Neptune’s rotation period is about 16 hours, but because the planet has no solid surface, different parts of its atmosphere rotate at different speeds. The equatorial regions spin more slowly than the poles, creating a dynamic interplay of jets and bands.

This differential rotation drives turbulence and helps explain the planet’s violent weather patterns. As winds interact with these rotating zones, massive storms form, migrate, and dissipate. The result is a planet in constant motion—a restless sea of gas and ice.

To observers, Neptune’s ever-changing patterns give it an almost living quality. Its clouds drift and twist, its spots appear and vanish. It is a planet that never stops breathing.

The Seasons of the Far Cold

Like Earth, Neptune is tilted on its axis—by about 28 degrees—which means it experiences seasons. But a Neptunian year lasts 165 Earth years, so each season endures for more than four decades.

Because sunlight is so faint at its distance, seasonal changes are subtle and slow. Yet modern telescopes have detected variations in Neptune’s brightness and storm activity that may correspond to these long, distant seasons. As the planet moves through its elliptical orbit, slight changes in solar energy may trigger shifts in atmospheric circulation, awakening or quieting storms.

Imagine a single summer lasting forty years, a winter lasting forty more—a world where change comes not in months, but in centuries. Neptune’s seasons unfold in the tempo of eternity.

The Symphony of the Outer Solar System

Neptune does not exist in isolation. Beyond it lies the Kuiper Belt—a vast realm of icy bodies, comets, and dwarf planets. In many ways, Neptune is the gatekeeper of this region. Its gravity shapes the orbits of countless objects, creating resonances that sculpt the outer Solar System.

Pluto, for instance, is in a 3:2 orbital resonance with Neptune, meaning it orbits the Sun twice for every three orbits of Neptune. Despite this, the two bodies never collide; their paths are locked in a graceful celestial dance choreographed by gravity itself.

Through its gravitational influence, Neptune defines the structure of the distant frontier. It stands as the last major planet before interstellar space—a sentinel marking the edge of the Sun’s domain.

The Future of Neptune Exploration

For more than three decades, Voyager 2’s brief encounter has remained our only direct glimpse of Neptune. But that is beginning to change. New proposals aim to return to this enigmatic world with orbiters and atmospheric probes that can study it in detail.

NASA’s proposed Trident mission, for example, would explore Neptune and Triton, searching for signs of active geysers and measuring the planet’s magnetic field and atmosphere. The European Space Agency and other groups have discussed similar missions, hoping to unlock the secrets of the deep blue giant.

Future explorers may one day drop probes into Neptune’s upper atmosphere, sampling its composition, measuring its winds, and witnessing its storms firsthand. Others may fly by Triton, watching its icy geysers erupt beneath the faint light of a distant Sun.

The scientific rewards would be immense—not only for understanding Neptune itself, but for interpreting exoplanets beyond our solar system. Many of the planets discovered around other stars are Neptune-like—icy giants cloaked in thick atmospheres. By understanding Neptune, we understand the universe.

Neptune and the Worlds Beyond

In the age of exoplanet discovery, Neptune has gained new importance. Thousands of planets have been found orbiting other stars, and a surprising number are “Neptune-sized”—roughly the same mass and composition as our distant blue giant.

These exoplanets, often called “mini-Neptunes” or “sub-Neptunes,” dominate our galaxy’s population. Yet Neptune remains our only nearby example, a laboratory for studying their nature. By understanding its storms, chemistry, and structure, scientists can infer the behavior of countless distant worlds we can only glimpse through faint starlight.

Thus, Neptune is not just a planet—it is a key, unlocking the mysteries of planetary formation across the cosmos.

The Poetry of a Distant World

There is something deeply poetic about Neptune. It lies at the edge of the Sun’s warmth, in a realm of cold shadows and endless silence. Yet within it burns energy, motion, and color. It is a paradox—the most distant planet, yet one of the most alive.

Its storms roar unseen, its clouds swirl in graceful arcs, its winds sing songs of speed and fury that no ear will ever hear. To imagine standing there—floating in its upper clouds, beneath an indigo sky streaked with ice crystals—is to imagine an alien beauty beyond words.

Neptune embodies the mystery of the universe itself: distant, cold, and indifferent, yet achingly beautiful.

The Eternal Blue Sentinel

As Voyager 2 looked back one last time after its flyby, Neptune appeared as a small, glowing orb fading into darkness. It was the last planet humanity had ever visited—the final chapter in our first great journey through the Solar System.

And yet, in that fading light, there was something eternal. Neptune stands as a symbol of exploration, of how far curiosity can reach. It whispers of the unknown worlds still waiting beyond, of storms yet unimagined, of beauty yet undiscovered.

Beneath its endless winds and deep blue storms, Neptune carries the story of the cosmos—of creation, destruction, and the fragile balance of forces that shape every world.

It is the last light before the stars. The windy world of deep blue storms, forever turning at the edge of our Sun’s embrace, forever reminding us that the universe is vast, mysterious, and full of wonder.

And though no human eyes may ever see its surface, Neptune will continue to dance through the darkness—silent, powerful, and endlessly alive—an eternal sapphire in the infinite night.