The Moon has always been humanity’s most intimate celestial companion. Suspended in the vast expanse of the night sky, it has guided travelers, inspired poets, and stirred the curiosity of scientists for millennia. Its pale, silent glow has watched over the rise and fall of civilizations, marking the passage of time and igniting our longing to reach beyond the confines of Earth. The Moon is more than a rock orbiting our planet—it is a mirror of our own story, a witness to the cosmic and human journey alike.

Every culture has woven myths around the Moon. To ancient peoples, it was a deity, a guardian, a clock that governed tides and time. To modern science, it is a relic of cosmic creation—a fragment of Earth’s early history, torn from its body billions of years ago. Yet whether viewed through the lens of myth or microscope, the Moon remains an eternal symbol of connection between heaven and Earth, between what we know and what we yearn to discover.

As our nearest neighbor in space, the Moon invites both familiarity and mystery. Its cratered face is visible even to the naked eye, yet its origins and inner secrets took centuries to uncover. It is both constant and changing, its phases shaping calendars, rituals, and tides. And though it seems tranquil, the Moon is a world of extremes—where searing heat and freezing cold alternate with the turn of a long lunar day.

The Birth of the Moon

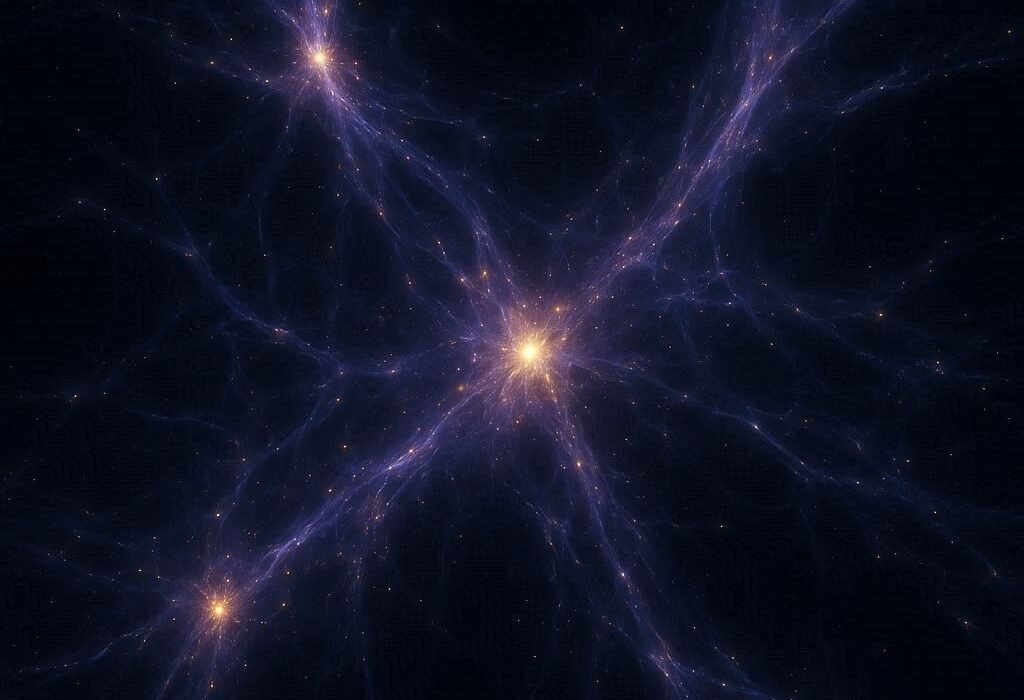

The story of the Moon’s birth begins nearly 4.5 billion years ago, in the fiery infancy of the Solar System. At that time, Earth was still molten, bombarded by debris left over from planetary formation. Then came a cataclysm—a collision so immense that it reshaped both worlds.

According to the prevailing giant impact hypothesis, a Mars-sized protoplanet named Theia struck the young Earth. The collision vaporized huge portions of both bodies, ejecting molten rock and metal into orbit. Over time, this debris coalesced under gravity to form the Moon. Evidence for this violent origin comes from the striking similarity between the isotopic compositions of lunar rocks and Earth’s mantle, suggesting a shared heritage.

This cataclysmic event was not merely destructive; it was transformative. The impact likely tilted Earth’s axis, giving rise to the seasons, and helped stabilize the planet’s rotation. The Moon, born from fire, became a guardian of Earth’s equilibrium—a silent partner ensuring that life could one day emerge and flourish.

A World of Dust and Stone

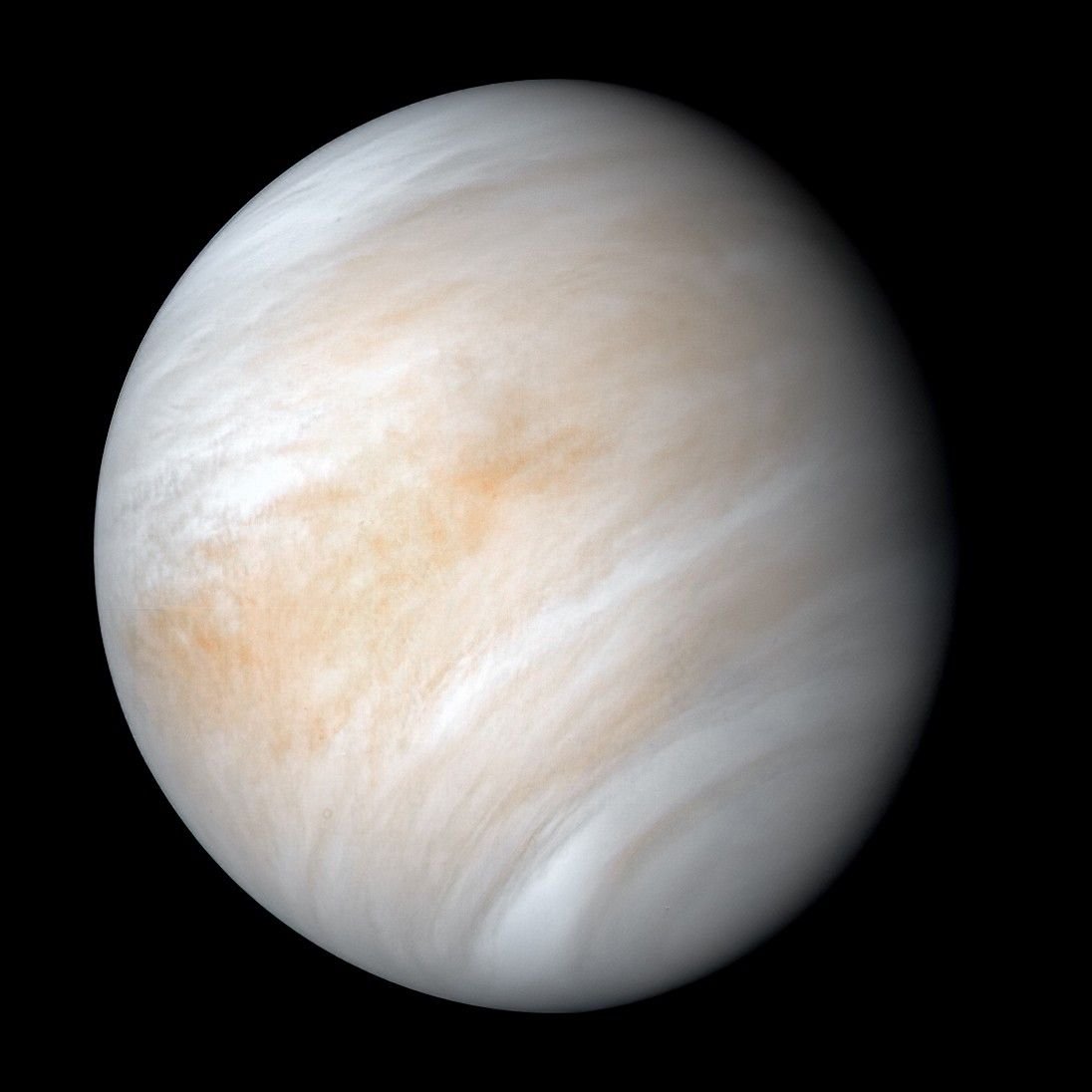

To the unaided eye, the Moon appears serene and unchanging, but its surface tells a tale of violence and time. Seen up close, it is a landscape of contrasts—vast plains, jagged mountains, and deep craters etched into ancient rock. These features are the scars of a billion impacts, frozen in time because the Moon has no atmosphere to erase them.

The large, dark patches we see from Earth are the maria—Latin for “seas.” Early astronomers thought they were oceans, but they are actually basaltic plains formed by volcanic eruptions billions of years ago. The lighter, more rugged highlands are older still, remnants of the Moon’s primordial crust. Craters such as Tycho and Copernicus gleam with bright rays of ejected material, reminders of more recent impacts that reshaped the surface.

Beneath its dusty exterior lies a complex interior. The Moon has a crust, mantle, and small metallic core, much like Earth’s, but with one crucial difference—it lacks the convective energy that drives plate tectonics. Its geological activity ended billions of years ago. Today, the only “weather” on the Moon comes from micrometeorites and solar radiation. The fine lunar dust, or regolith, formed by countless impacts, clings to everything—an abrasive, electrified powder that future explorers must contend with.

Yet the Moon is not completely inert. Tiny “moonquakes,” triggered by tidal stresses from Earth’s gravity, occasionally ripple through its crust. These subtle tremors remind us that even a seemingly dead world is still connected to the living planet it orbits.

The Dance of Light and Shadow

The Moon’s ever-changing face has captivated humanity since time immemorial. Its phases—new, crescent, quarter, gibbous, and full—arise from its orbit around Earth and the interplay of sunlight and shadow. In one lunar month, about 29.5 days, the Moon completes a full cycle of phases, waxing and waning as it travels across the sky.

The rhythm of the Moon’s phases has shaped human culture profoundly. Ancient calendars were based on its cycle, religious festivals were timed by its light, and harvests were planned according to its glow. The word “month” itself derives from “moon,” a linguistic echo of this ancient dependence.

Yet this cycle also reveals the Moon’s subtle secrets. The same side of the Moon always faces Earth—a phenomenon known as synchronous rotation or tidal locking. This occurs because Earth’s gravity slowed the Moon’s rotation over millions of years until its spin matched its orbit. As a result, one hemisphere perpetually gazes upon us while the other, the far side, remained unseen until spacecraft revealed it in the 20th century.

The far side of the Moon is not truly “dark,” but it is markedly different. Its surface is heavily cratered and lacks the vast maria that dominate the near side. This asymmetry likely arose from differences in crustal thickness and thermal evolution during the Moon’s early history. The far side is also shielded from much of Earth’s radio interference, making it an ideal site for future radio astronomy observatories.

The Power of Tides

The gravitational bond between Earth and the Moon is a dance of mutual influence. The Moon’s gravity tugs at Earth’s oceans, raising bulges that move around the globe as tides. These tides are not mere curiosities—they have shaped our planet’s ecosystems, coastlines, and even the evolution of life itself.

As the Moon pulls on Earth’s oceans, friction slows the planet’s rotation slightly, while the Moon drifts away at about 3.8 centimeters per year. This delicate exchange of energy has been ongoing for billions of years. In Earth’s early history, days were shorter—only about 18 hours long—and the Moon was much closer, looming large in the sky.

Tides also reveal the profound interdependence between Earth and its satellite. The lunar tides mix nutrients in coastal waters, influence biological rhythms in marine life, and create intertidal zones—unique habitats that may have nurtured the first steps of life from sea to land. Without the Moon’s steadying influence, Earth’s tilt could wobble chaotically, leading to extreme climate shifts. The Moon is not only a companion but a stabilizer, a quiet architect of our planet’s habitability.

The Moon in Human Imagination

Long before telescopes, the Moon captured humanity’s imagination. Its changing phases and mysterious glow made it a symbol of transformation, fertility, and time. Ancient Sumerians associated it with Nanna, the god of wisdom. The Greeks called it Selene and Artemis, radiant deities of night and purity. In Chinese mythology, the Moon is home to Chang’e, the goddess who drinks the elixir of immortality.

The Moon’s influence permeates art, literature, and religion. Poets have likened it to a lover, a mirror, a muse. Painters captured its light on water and stone. Even in science, the Moon’s pull was once seen as mystical—giving rise to the word lunacy, from luna, the Latin for Moon, reflecting the belief that it affected human behavior.

When Galileo turned his telescope skyward in 1609, he shattered the illusion of perfection that philosophers once ascribed to the heavens. He saw mountains, valleys, and shadows—proof that the Moon was a world, not a divine orb. That realization forever changed humanity’s place in the cosmos. The Moon was no longer a distant symbol; it was a destination.

The Age of Exploration

The mid-20th century marked the dawn of a new chapter in humanity’s relationship with the Moon—the era of space exploration. In 1959, the Soviet probe Luna 2 became the first human-made object to impact the Moon, followed by Luna 3, which sent back the first images of the far side. These milestones ignited a space race that culminated in one of humanity’s greatest triumphs.

On July 20, 1969, Apollo 11 astronauts Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin set foot on the lunar surface, while Michael Collins orbited above. Armstrong’s words—“That’s one small step for man, one giant leap for mankind”—echoed across the planet. The Moon, once a symbol of unreachable beauty, became a place touched by human hands.

Between 1969 and 1972, six Apollo missions successfully landed twelve astronauts on the Moon. They conducted experiments, collected rocks, and left behind instruments that still send data to Earth. The lunar soil they brought back revealed that the Moon’s surface is rich in oxygen, silicon, iron, and titanium—materials that could one day support lunar industry.

The Apollo era ended, but the fascination never did. In recent years, renewed interest has emerged. Robotic missions from China, India, Japan, and the United States have mapped the Moon in unprecedented detail, discovered water ice in shadowed craters, and tested technologies for future human return. The Moon, it seems, is once again within reach.

The Science of the Moon

Modern lunar science, or selenology, explores the Moon’s origin, geology, and potential resources. The samples returned by the Apollo missions transformed our understanding of planetary evolution. Lunar rocks, nearly devoid of water and atmosphere-derived compounds, bear witness to a world untouched by weather. Their isotopic ratios mirror those of Earth, reinforcing the idea of a shared origin.

Recent discoveries have added new layers of intrigue. Water, once thought absent, has been detected as ice in permanently shadowed regions near the poles. These reserves, preserved in cold traps for billions of years, could provide fuel and drinking water for future missions. The Moon also holds valuable elements such as helium-3, a rare isotope with potential for fusion energy.

By studying the Moon, scientists also peer into the Solar System’s past. Its unaltered surface preserves the record of asteroid impacts, solar radiation, and volcanic activity stretching back billions of years. Unlike Earth, whose surface renews through tectonics and erosion, the Moon is a time capsule—a geological library of cosmic history.

The Lunar Environment

Life on the Moon is a formidable challenge. Its environment is hostile to human survival—airless, waterless, and subject to brutal extremes. Daytime temperatures soar above 120°C, while nighttime plunges below -170°C. Without an atmosphere, the sky remains black even at noon, and cosmic radiation bombards the surface unabated.

Dust poses a serious hazard as well. Lunar regolith is composed of sharp, glassy particles that cling to equipment and spacesuits, causing abrasion and respiratory risks. Future missions will need to devise ways to manage this dust, perhaps through electrostatic systems or sealed habitats.

Yet amid these challenges lie opportunities. The Moon’s low gravity, about one-sixth that of Earth’s, makes it an ideal base for launching missions deeper into space. Its poles, with near-constant sunlight on some ridges and eternal darkness in nearby craters, offer potential sites for both solar power and resource extraction. The Moon could become humanity’s first true stepping stone beyond Earth.

The Return to the Moon

In the 21st century, a new wave of lunar exploration has begun. NASA’s Artemis program aims to return humans to the Moon and establish a sustainable presence. The first woman and the next man are planned to walk its surface in coming years, building upon the legacy of Apollo with advanced technology and international collaboration.

Other nations, too, are reaching for the Moon. China’s Chang’e missions have landed rovers and returned samples. India’s Chandrayaan-3 achieved a historic soft landing near the lunar south pole. Private companies, spurred by partnerships and competition, are developing landers, rovers, and habitats. Humanity is no longer merely visiting the Moon—it is preparing to live and work there.

The Moon’s role in this new era extends beyond exploration. It offers a proving ground for technologies needed to reach Mars and beyond. Lunar habitats will teach us how to survive in low gravity, recycle air and water, and harness local materials. The Moon is, in a sense, our cosmic laboratory for the future.

The Moon and Earth: A Cosmic Relationship

The connection between Earth and Moon is profound, extending far beyond gravity. They are bound by their shared past and mutual evolution. The Moon stabilizes Earth’s axial tilt, moderates climate, and shapes biological rhythms. In return, Earth’s gravity sculpts the Moon’s orbit, causing its face to always look toward us.

The Moon’s distance from Earth slowly increases, changing the dynamics of tides and the length of our days. In hundreds of millions of years, total solar eclipses—those perfect alignments of Sun, Moon, and Earth—will cease to occur as the Moon drifts farther away. Even the cosmic dance has an end.

And yet, for as long as it remains, the Moon will continue to shape life on our planet. It has been our calendar, our muse, our mirror. Its light has guided migrations, inspired religions, and synchronized the cycles of countless living things. In every sense, the Moon is part of what makes Earth home.

The Moon in the Human Soul

Why does the Moon move us so deeply? Perhaps because it embodies both constancy and change. It is always there, yet always different—waxing, waning, vanishing, and returning. Its glow evokes both loneliness and comfort, its silence both distance and intimacy.

To gaze at the Moon is to confront the duality of existence: permanence and impermanence, stillness and motion, solitude and connection. It reminds us that even in darkness, light endures. It whispers of cycles beyond our control, of a universe that moves in rhythm with unseen laws.

When the Apollo astronauts looked back at Earth from the Moon, they saw our planet as a fragile blue sphere suspended in blackness. That image, known as the “Earthrise,” transformed how humanity saw itself—not as nations divided, but as one species beneath a shared sky. The Moon, our silent witness, became the mirror through which we recognized our unity.

The Future Awaits

As humanity prepares to return to the Moon, the questions it holds grow ever more profound. Can we live sustainably beyond Earth? Can lunar resources support future colonies? Can the Moon serve as a launchpad for journeys to Mars and beyond?

The Moon’s past and future intertwine with our own. Its creation from Earth’s flesh, its guardianship of our tides and stability, its role as the first world humans ever touched—all make it both our child and our ancestor. To explore it again is not just an act of science, but a continuation of an ancient bond.

In the decades ahead, lights may once again gleam on the Moon’s horizon—human settlements, observatories, and laboratories. The Moon, once only a dream, will become a home for those who dare to extend the reach of life itself. And when they look back upon Earth, glowing softly in the lunar sky, they will see the world that gave birth to both them and the Moon, bound forever in a cosmic embrace.

The Eternal Companion

The Moon is more than a celestial body; it is a testament to the interconnectedness of all things. It teaches us that even separation is a form of unity—that in drifting away, it still shapes our fate. Its light is ancient sunlight, reflected across the abyss, whispering that distance can never diminish connection.

For billions of years, the Moon has watched Earth’s oceans surge and life evolve, continents drift, and civilizations rise beneath its glow. Long after our species has moved on, its pale light will still sweep across the darkened plains, faithful as ever.

The Moon is the memory of our beginnings and the beacon of our future. It is Earth’s eternal companion in the night—a silent partner in the cosmic waltz, reminding us that in every orbit, in every reflection of light and shadow, lies the timeless truth of belonging.