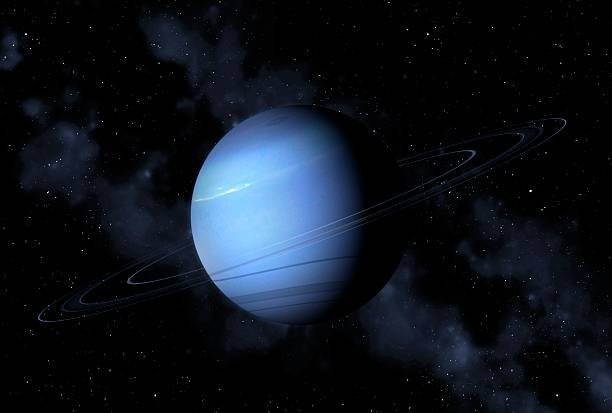

Far beyond the warmth of the Sun, where light is dim and the Solar System fades into frozen silence, orbits a world unlike any other—Triton, Neptune’s largest moon and one of the most enigmatic objects ever discovered. It circles its planet in the cold frontier of our cosmic neighborhood, where the sunlight is a thousand times weaker than on Earth and the temperature hovers near absolute zero. Yet, beneath its icy surface, Triton harbors mystery, motion, and perhaps even the faint whispers of life’s potential.

Triton is a paradox—a moon that moves backward, a frozen sphere that erupts with icy plumes, a captured wanderer that defies every expectation. It is not merely Neptune’s moon; it is a cosmic refugee, a survivor of ancient chaos. Its story tells of capture and transformation, of rebellion against the orderly dance of the planets, and of the forces that shaped the Solar System itself.

In the desolate reaches beyond Saturn, only a few spacecraft have ever dared to venture. Of those, only one—Voyager 2, in 1989—has seen Triton up close. What it revealed was astonishing: a landscape of frozen nitrogen, pinkish ices, dark streaks from erupting geysers, and plains so smooth they seemed freshly formed. Triton was alive, geologically speaking, even in the deep freeze of the outer Solar System.

The Discovery of a Distant Enigma

Triton was discovered on October 10, 1846, by British astronomer William Lassell, just 17 days after the discovery of Neptune itself. Lassell, using a telescope of his own construction, was one of the first to turn his instrument toward the new planet. What he found orbiting it was a faint, starlike point of light—one that would later prove to be Neptune’s largest moon.

At the time, little was known about the outer Solar System. The discovery of Uranus in 1781 and the subsequent detection of Neptune had already expanded humanity’s sense of cosmic scale. Triton, smaller and dimmer than any of the inner moons we knew, was nonetheless a monumental find. Over the next century, astronomers would gradually determine its size, orbit, and peculiar behavior.

What stood out most was Triton’s motion. Unlike most moons, which orbit their planets in the same direction as the planet’s rotation, Triton moves in the opposite direction—a retrograde orbit. This was no trivial quirk; it hinted at an extraordinary past. A retrograde orbit cannot form naturally from a planet’s original disk of material. Triton, it seemed, was not born of Neptune. It was an interloper, a captured body—something that had wandered too close and been ensnared by the giant planet’s gravity.

A Captured Rebel

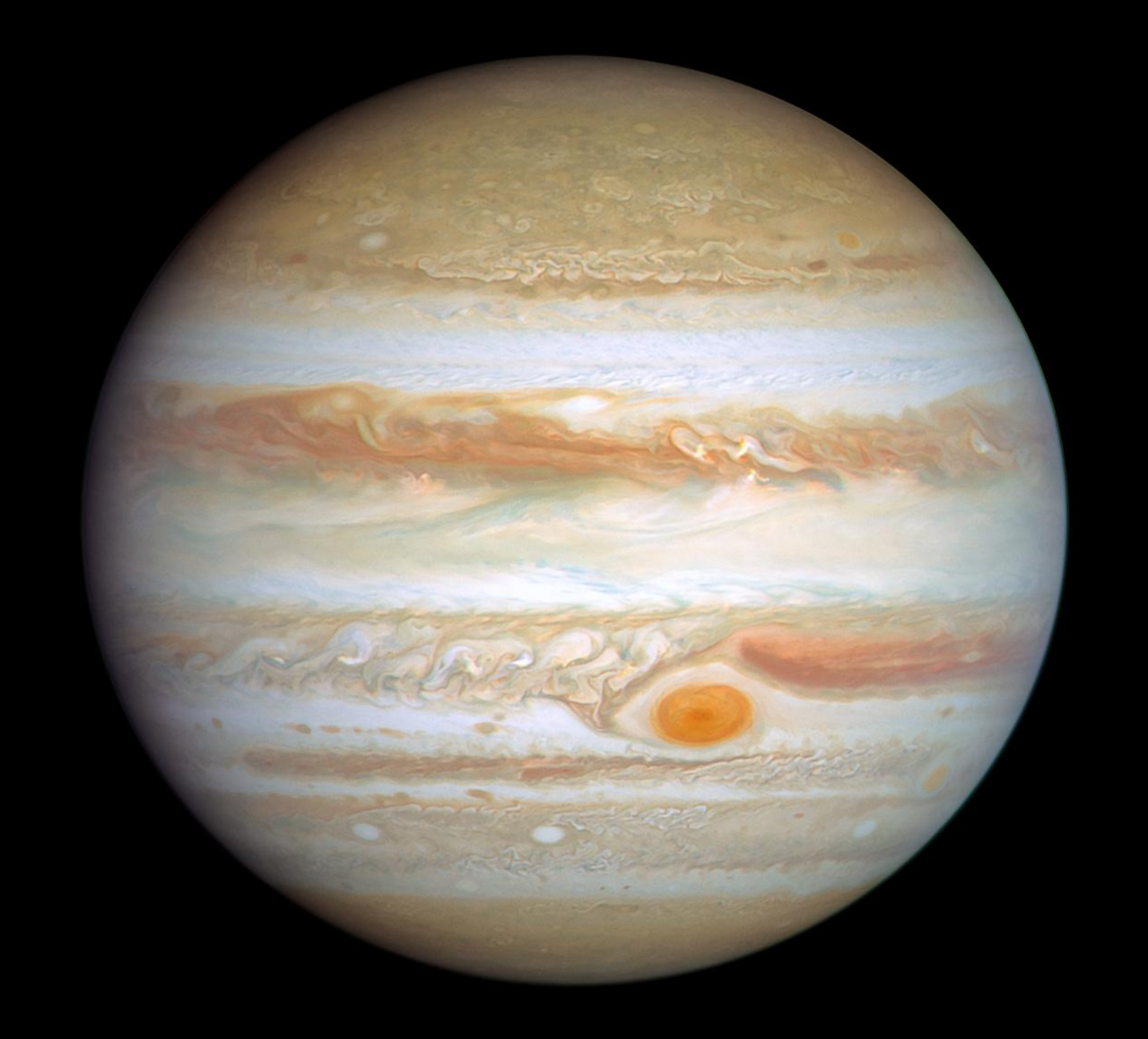

Triton’s orbit remains one of the great clues to its origin. It is tilted at an angle of 157 degrees relative to Neptune’s equatorial plane and circles the planet once every 5.9 Earth days. Such a configuration defies the standard rules of planetary formation. Most moons, like those of Jupiter or Saturn, coalesced from disks of gas and dust surrounding their parent planets. Triton’s retrograde motion, however, implies an entirely different story.

Scientists now believe Triton began its life as a member of the Kuiper Belt—the vast ring of icy objects beyond Neptune that includes Pluto, Eris, and countless smaller bodies. In this distant realm, frozen remnants of the early Solar System still drift in slow, sunless orbits. Triton, it appears, was once one of them—a dwarf planet, large enough to be spherical, possibly with its own moons.

At some point in the deep past, Triton’s path brought it dangerously close to Neptune. A complex gravitational encounter ensued—perhaps involving another moon or binary companion—and Triton was captured. This event would have been catastrophic: the sudden gravitational tug tore away its former companion, locked Triton into a retrograde orbit, and released enormous amounts of heat as the orbit circularized.

The capture transformed both worlds. Neptune’s original moons, if it had any, would have been destabilized and ejected or destroyed by Triton’s arrival. The energy of capture likely melted Triton’s interior, setting the stage for its later geological activity. From that moment onward, Triton became the rebel moon—an adopted child of Neptune, forever moving against the flow of its host planet’s rotation.

The Face of an Alien World

When Voyager 2 flew past Neptune in August 1989, it changed everything we knew about the outer Solar System. For the first time, humanity saw Triton not as a distant point of light but as a world. The spacecraft’s cameras captured sweeping views of a strange and hauntingly beautiful moon—a place both ancient and new, where ice behaved like rock and nitrogen flowed like water.

Triton’s surface is a patchwork of alien terrains. Some regions are smooth and unblemished, others marked by pits, ridges, and frozen rivers. The lack of impact craters suggests that much of the surface is geologically young, perhaps less than 100 million years old. This was an astonishing revelation for a world so far from the Sun, where one might expect only silence and stasis.

The most striking features were the cryovolcanoes—ice geysers erupting from the surface, spewing nitrogen gas and dark dust miles into the thin atmosphere. Voyager captured several plumes rising eight kilometers high, leaving long streaks on the plains as the wind carried the material downrange. These geysers hinted at internal heat, likely generated by the slow gravitational flexing caused by Neptune’s tides.

One vast region, known as the cantaloupe terrain for its wrinkled appearance, consists of domes and pits unlike anything seen elsewhere in the Solar System. Another, called Ruach Planitia, is a smooth, reflective plain of frozen nitrogen, methane, and carbon monoxide. The patterns of ridges and fractures across Triton’s face suggest a history of expansion and contraction, as if the surface were stretched and refrozen repeatedly over time.

Triton’s coloration also sets it apart. Its surface is tinged with pinkish hues, caused by complex organic molecules known as tholins, formed when ultraviolet light and cosmic rays strike frozen methane. These tholins are thought to exist on many icy bodies, including Pluto and Titan, and they lend Triton a delicate rose tint amid the gray-white frost.

The Atmosphere of a Frozen World

Despite its distance from the Sun, Triton possesses a tenuous atmosphere—a whisper of gases suspended above the ice. Voyager 2 detected nitrogen, methane, and carbon monoxide forming a layer only a few microbars in pressure, about 70,000 times thinner than Earth’s. Yet this fragile shroud plays a dynamic role in Triton’s climate and surface activity.

The atmosphere is sustained by the sublimation of nitrogen ice from the surface. As sunlight warms Triton’s sunlit hemisphere, nitrogen turns to vapor and flows toward colder regions, where it refreezes. This cycle of sublimation and condensation drives winds and possibly contributes to the plumes seen by Voyager. Triton’s atmosphere also exhibits seasonal variation, thickening slightly as the Sun’s angle changes during Neptune’s 165-year orbit.

In 2010 and 2017, astronomers using the Hubble Space Telescope and ground-based observatories detected changes in Triton’s brightness, suggesting that the atmosphere may be expanding as it moves toward a warmer season. Even in the deep cold—temperatures hover near 38 Kelvin (−235°C)—Triton remains a world in motion, its frozen nitrogen behaving like Earth’s water in miniature cycles of evaporation and condensation.

The faint haze and clouds observed by Voyager hint at winds moving across the surface, sculpting streaks of dark material that stretch for hundreds of kilometers. These winds, though weak, are evidence that even the farthest moons can breathe, however faintly, in the eternal cold.

The Hidden Ocean Beneath the Ice

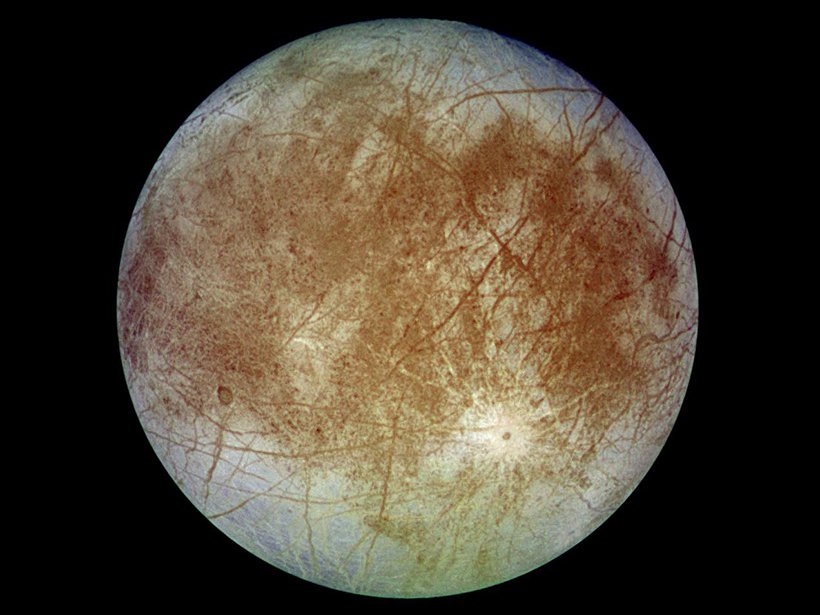

Beneath Triton’s frozen crust may lie one of the most tantalizing secrets of all—a subsurface ocean. In recent years, evidence has mounted that many icy moons, including Europa, Enceladus, and Ganymede, possess liquid water beneath their shells, kept from freezing by tidal heating and the presence of salts or ammonia. Triton, too, fits this pattern.

Models suggest that after its capture, Triton’s interior was heated enough to melt large portions of its ice, possibly forming an ocean that still lingers beneath the surface. The presence of active geysers and tectonic features indicates that internal heat persists, likely generated by radioactive decay and residual tidal flexing.

If such an ocean exists, it could be tens of kilometers below the surface—dark, pressurized, and possibly rich in dissolved gases. Though the chances of life there remain speculative, the ingredients are intriguing. Energy, liquid water, and organic compounds—all essential components for biology—are theoretically present. In this sense, Triton joins the growing list of “ocean worlds” in the Solar System, places where the potential for microbial life lingers beneath ice.

Future missions, perhaps equipped with radar sounders or landers, could confirm the presence of this hidden sea. If discovered, it would reshape our understanding of where life might arise, even in the remotest corners of our cosmic neighborhood.

The March Toward Destruction

Triton’s story is not only one of birth and mystery—it is also one of slow, inevitable doom. Its retrograde orbit, while fascinating, is also its curse. Because it moves against Neptune’s rotation, tidal forces between the two bodies act to shrink Triton’s orbit gradually. Over millions of years, it is spiraling inward, drawing ever closer to its planet.

Eventually—perhaps in 100 million to 500 million years—Triton will cross Neptune’s Roche limit, the distance at which tidal forces exceed its internal gravity. When that moment comes, Triton will begin to break apart, its fragments forming a magnificent ring system around Neptune. The planet, now adorned with faint, dusty arcs, may one day rival Saturn in splendor, its new rings born from the death of its largest moon.

This cosmic fate is a reminder of the impermanence of all celestial structures. Just as Triton was once a wanderer captured by Neptune, so too will it be torn apart by the same gravitational bond that holds it. The story of Triton is thus a story of cycles—capture, transformation, decay—and the eternal reshaping of worlds.

Voyager 2’s Legacy

Our only encounter with Triton came during the fleeting days of Voyager 2’s historic journey through the outer Solar System. In August 1989, after studying Jupiter, Saturn, and Uranus, the spacecraft swept past Neptune at a distance of 4,950 kilometers and captured humanity’s first—and so far only—close views of Triton.

The data sent back transformed our understanding of icy moons. Voyager’s images revealed active geology in one of the coldest environments imaginable, challenging assumptions that distant worlds must be dead and inert. It showed plumes of nitrogen rising like geysers, smooth plains that hinted at resurfacing, and a world sculpted by internal forces despite its frozen state.

The flyby lasted only hours, but its legacy endures. For decades, planetary scientists have dreamed of returning to Triton. NASA has proposed several missions, including Trident, a flyby probe that would map the surface, study the atmosphere, and search for signs of a subsurface ocean. If approved, such a mission could launch in the early 2030s and reach Neptune around 2040, offering a long-awaited second glimpse of this rebel moon.

A Cousin to Pluto

In many ways, Triton is Pluto’s twin separated by fate. Both are similar in size, composition, and surface chemistry. Both are covered in frozen nitrogen and methane and display pinkish hues from organic compounds. Both may harbor internal oceans and experience cryovolcanic activity.

But where Pluto remained free in its orbit around the Sun, Triton was captured and bound to a planet’s gravity. Their shared origin in the Kuiper Belt explains these resemblances, yet their destinies diverged profoundly. Studying Triton thus helps scientists understand the history of other icy worlds—and vice versa. The New Horizons mission, which visited Pluto in 2015, provided context that enriches our interpretation of Triton. Together, these two worlds illustrate the diversity of the outer Solar System and the complex processes that shaped it.

Seasons Under a Distant Sun

Like Neptune, Triton experiences seasons that last more than 40 years each, owing to the planet’s long orbital period around the Sun. As sunlight shifts between hemispheres, ices sublime and refreeze, driving slow, planet-wide changes. During southern summer—when Voyager visited—the south pole was bathed in sunlight, and nitrogen frost was evaporating, feeding the thin atmosphere and creating the observed geysers.

As the seasons shift, this pattern reverses. Northern regions, once dark and frozen, now emerge into light, while the southern plains plunge into darkness. Scientists tracking Triton’s brightness have seen hints of this transition, suggesting a dynamic, evolving surface even in the frozen reaches of space.

These slow, majestic seasons remind us that time flows differently at the edge of the Solar System. A single Tritonian year outlasts a human lifetime several times over. Change comes in centuries, not days—yet it comes nonetheless, written in ice instead of water, and wind instead of rain.

The Allure of the Unknown

Triton remains one of the least-explored yet most fascinating worlds in our Solar System. It challenges our understanding of planetary science, blurring the boundaries between moon and planet, between frozen and alive. Its backward orbit, its geysers, its possible ocean—all defy the expectations of a world so far from the Sun.

For scientists, Triton is a window into the early Solar System and the processes that govern distant icy worlds. For dreamers, it is a symbol of cosmic rebellion—a wanderer that refused to conform, that found a new home by defying the rules. For humanity, it stands as an invitation: to return, to explore, and to discover what secrets lie hidden beneath its ancient ice.

The Meaning of Triton

In mythology, Triton was the son of Poseidon, god of the sea, who calmed the waves by blowing his conch shell. The name suits this distant moon, for it too moves in the realm of a cosmic ocean, circling a planet named for the Roman god of the sea. But there is irony in the mythic parallel—this Triton is no obedient servant but a captured rebel, forever moving against Neptune’s spin.

To study Triton is to witness the tension between order and chaos, gravity and freedom, destiny and defiance. It reminds us that the Solar System is not static but dynamic, a theater of collisions and captures, of creation born from destruction. Triton’s orbit tells of violence, but its surface tells of renewal—a frozen world that still breathes in the dark.

The Future of Exploration

As we look toward the next century of space exploration, Triton beckons as one of the last great frontiers. A mission there could answer fundamental questions: How do captured moons evolve? Can life exist beneath ice in the outer Solar System? What does Triton reveal about Neptune, its atmosphere, and the evolution of distant worlds?

Such a mission would not only advance science but rekindle the spirit of discovery that propelled Voyager 2. It would remind us that even the coldest places can hold warmth in the form of curiosity and wonder. Triton, silent and distant, calls to us across billions of kilometers—not just as an object of study, but as a symbol of resilience and cosmic adventure.

The Rebel’s Legacy

In the end, Triton is a story of contradictions. It is both moon and former planet, both frozen and active, both captive and free. Its backward orbit mocks convention; its hidden ocean whispers of life where none should exist. It is a reminder that even in the farthest reaches of darkness, creation and change persist.

When we gaze into the night sky and imagine Neptune, faint and blue at the edge of vision, Triton is there—circling silently in defiance, its pink frost reflecting the dim sunlight from four billion kilometers away. It is the rebel of the outer darkness, a world stolen from the stars yet still dreaming of the freedom it once knew.

Triton, Neptune’s captured moon, remains one of the universe’s most compelling enigmas—a frozen wanderer that found a home in captivity, a reminder that even in bondage, there can be beauty, motion, and mystery. And as long as Neptune’s blue storms rage beneath it, Triton will continue its lonely, backward dance—a cosmic testament to the strange and wondrous ways the universe shapes its children.