At first glance, it seems like a paradox — a planet so close to the Sun that its daytime surface can melt lead, yet home to frozen water locked in eternal shadow. This is Mercury, the innermost world of our Solar System, a place of extremes where scorching sunlight and frigid darkness coexist side by side. For centuries, Mercury was thought to be a barren, lifeless rock, baked dry by the relentless solar heat. But as spacecraft began to unveil its secrets, scientists discovered something astonishing: ice.

How can ice survive on a planet where daytime temperatures soar above 430 degrees Celsius? The answer lies in Mercury’s unique dance with the Sun, its rugged terrain, and the profound silence of its polar shadows. Here, in the planet’s deepest craters — untouched by sunlight for billions of years — lies a frozen record of the Solar System’s ancient past.

Mercury is both a world of contradictions and a messenger from the dawn of creation. It is the smallest of the eight planets, yet one of the most mysterious; the fastest to orbit the Sun, yet the slowest to rotate on its axis. To understand Mercury is to glimpse the delicate balance between destruction and preservation that defines the universe itself.

The Swift Messenger of the Sky

Mercury takes its name from the Roman god of speed — the fleet-footed messenger who darted between heaven and Earth. True to its name, Mercury races around the Sun in just 88 Earth days, moving faster than any other planet. Yet from Earth’s surface, this elusive world is difficult to see. It never strays far from the Sun’s glare, appearing only briefly at dawn or dusk, a fleeting spark in the twilight sky.

Ancient civilizations struggled to comprehend its dual appearances. To the Babylonians, it was Nabu, the god of wisdom. The Greeks thought they saw two different stars — Apollo in the morning and Hermes in the evening — until they realized both were the same planet. Mercury’s elusive nature made it a symbol of transformation and transience, a celestial trickster that defied easy observation.

Only with the advent of telescopes and, later, space missions did Mercury begin to yield its secrets. Early astronomers such as Giovanni Schiaparelli and Percival Lowell believed the planet was tidally locked — showing the same face to the Sun, like the Moon to Earth. It wasn’t until 1965, through radar observations from Earth, that scientists discovered the truth: Mercury rotates three times for every two orbits around the Sun. This 3:2 resonance gives the planet its bizarre rhythm of days and nights, creating some of the most extreme temperature contrasts in the Solar System.

A Planet of Extremes

Mercury’s proximity to the Sun subjects it to an environment of staggering contrasts. At high noon, temperatures soar to 430°C, hot enough to vaporize zinc and tin. Yet during the long, airless night, the heat escapes into space, and the surface plummets to -180°C. Such extremes would destroy any semblance of atmosphere, and indeed, Mercury’s is almost nonexistent — a tenuous exosphere made up of atoms blasted from the surface by the solar wind.

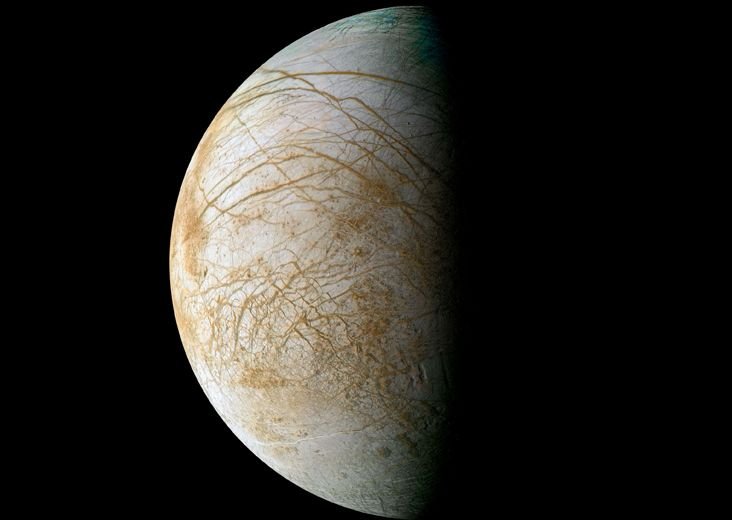

Without an atmosphere to spread heat or shield it from meteoroids, Mercury’s landscape is ancient and scarred. It resembles our Moon in many ways, pocked with craters, ridges, and plains that record billions of years of bombardment. Towering cliffs called lobate scarps stretch for hundreds of kilometers, formed as the planet’s interior cooled and contracted. Mercury, it seems, has been shrinking slowly over geological time — a world tightening its rocky skin as it ages.

Despite its small size — only slightly larger than Earth’s Moon — Mercury is dense, with a massive iron core making up about 85 percent of its radius. This makes it the second densest planet in the Solar System, surpassed only by Earth. The size of its metallic heart suggests a dramatic origin story, perhaps involving a colossal collision that stripped away much of its original crust.

A Fragile Envelope of Atoms

Mercury’s thin exosphere is unlike any atmosphere on Earth. It is so insubstantial that a single breath would scatter its molecules into space. Composed mainly of oxygen, sodium, hydrogen, helium, and potassium, this ghostly envelope is constantly replenished by the solar wind and by micrometeorites striking the surface.

This delicate balance between erosion and renewal gives Mercury a dynamic character despite its apparent stillness. Sodium atoms, for example, are ejected from the surface by sunlight and can form glowing tails that extend thousands of kilometers into space, faintly reminiscent of a comet’s. These ephemeral phenomena remind us that even the smallest worlds are not dead, but alive in their interaction with the cosmic environment.

The solar wind — a stream of charged particles from the Sun — also plays a crucial role. It sculpts Mercury’s magnetic field, compressing it on the dayside and elongating it on the nightside. The result is a magnetosphere that, though small, is surprisingly strong for such a tiny planet. Mercury’s internal magnetic field, about 1 percent as strong as Earth’s, hints at a partially molten core still churning within — a remnant of the planet’s fiery youth.

The Long Day and the Cold Night

One of the most intriguing aspects of Mercury is its day — a single rotation lasts about 59 Earth days, while its year is only 88. This peculiar 3:2 spin-orbit resonance means that a solar day — the time from one sunrise to the next — lasts about 176 Earth days. Imagine standing on Mercury: the Sun would rise slowly, growing larger and brighter until it blazes nearly three times wider than it does from Earth. It would then pause, move backward slightly in the sky due to orbital motion, and continue its slow arc toward the horizon.

During this protracted day, the surface bakes under unfiltered sunlight, while the nightside plunges into frigid darkness for months at a time. These alternating extremes created the conditions that make Mercury’s hidden ice possible. At its poles, where sunlight never touches certain crater floors, temperatures remain below -170°C — cold enough for water ice to persist for billions of years.

The Mystery of Ice on Mercury

For decades, scientists assumed Mercury was utterly devoid of volatiles — substances that easily vaporize, such as water, carbon dioxide, or methane. How could ice survive on a world so close to the Sun? The idea seemed impossible, until the late 20th century brought surprising evidence.

In 1991, radar observations from Earth-based telescopes revealed bright, reflective patches near Mercury’s poles. These radar-bright regions resembled signals seen from icy surfaces elsewhere in the Solar System, such as on the icy moons of Jupiter. The discovery hinted at the unthinkable: Mercury might harbor water ice in permanently shadowed craters.

This suspicion was confirmed decades later by NASA’s MESSENGER spacecraft. Launched in 2004, MESSENGER became the first probe to orbit Mercury in 2011. Using neutron spectrometry and imaging, it detected hydrogen-rich deposits precisely where the radar reflections appeared. These findings confirmed that the bright spots were indeed ice — protected for eons in regions so cold that sunlight never reaches them.

The ice likely originated from comets and asteroids that struck Mercury over billions of years, delivering water and organic compounds. Some may also have come from the planet’s own interior, released by volcanic activity and later trapped in the poles’ deep shadows. This frozen material forms a fragile archive of Solar System history, preserving the chemistry of the early planets.

Shadows of Eternal Night

The key to Mercury’s icy paradox lies in its axial tilt — or rather, the lack of it. Unlike Earth, which tilts about 23.5 degrees, Mercury’s spin axis is tilted by less than one degree. This near-perfect alignment means the Sun’s rays never reach the floors of some polar craters.

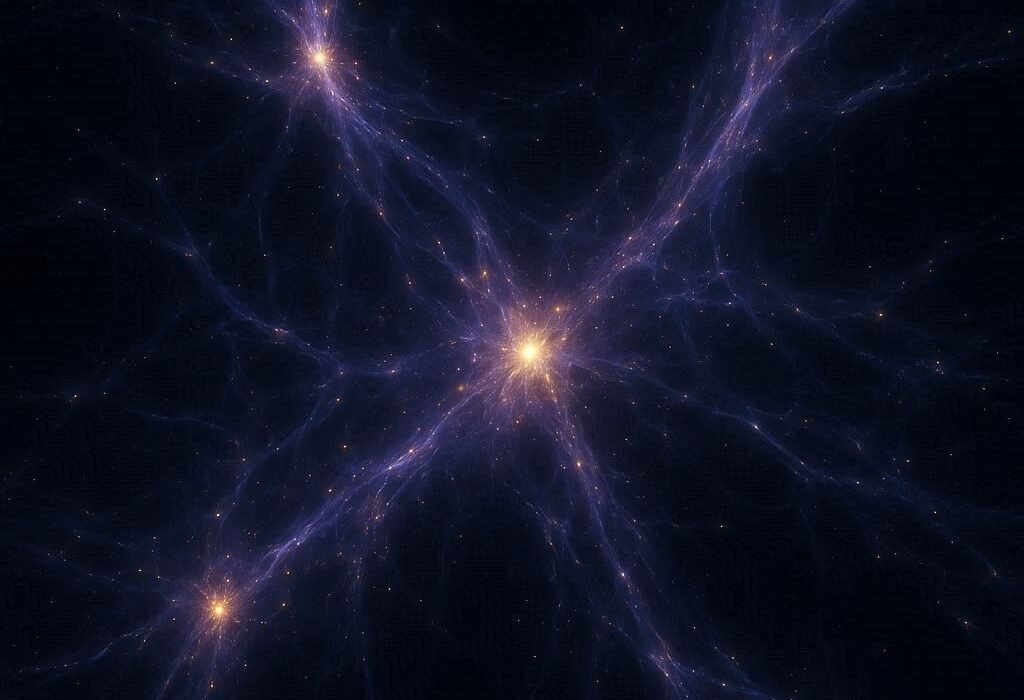

Within these perpetual shadows, sunlight is absent, and heat cannot penetrate. The temperatures there are among the coldest in the Solar System — even colder than the surface of Pluto. These regions, known as “cold traps,” act as natural freezers. Water molecules migrating across Mercury’s surface are captured and held in place, unable to escape into space.

MESSENGER revealed that these cold traps contain thick deposits of nearly pure water ice, covered in some places by a thin layer of dark organic material. This dark mantle may be carbon-rich residue from the same impacts that delivered the water, acting as insulation that helps the ice persist.

The existence of ice on Mercury is not merely a curiosity; it is a profound insight into planetary evolution. It shows that even in the hottest regions of the Solar System, nature finds niches where opposites coexist — heat and cold, light and darkness, destruction and preservation.

A Record of Cosmic History

The ice in Mercury’s polar craters is more than frozen water — it is a time capsule from the early Solar System. Each molecule trapped in those shadows may have journeyed across billions of years, carrying the chemical fingerprints of ancient comets. Studying it could reveal the origins of water on rocky planets, including Earth.

Mercury’s craters also preserve a record of bombardment history. Because the planet has no atmosphere to erode its surface, impact scars remain almost perfectly preserved. Some date back more than four billion years, offering clues about the violent era known as the Late Heavy Bombardment, when the inner planets were pummeled by asteroids and comets.

The presence of water ice raises tantalizing questions. Could similar mechanisms have once operated on other airless bodies, like the Moon or asteroids? Could the ingredients of life have been delivered across the Solar System in this way? Mercury’s frozen craters, silent and dark, may hold the answers.

Mercury’s Volcanic Past

Though Mercury now appears geologically quiet, its surface tells a story of intense volcanic activity in its youth. Vast plains of solidified lava stretch across the planet, filling ancient basins and smoothing over older craters. Some of these lava flows are hundreds of kilometers long, evidence of a time when the planet’s interior was hot and active.

The most famous impact basin, the Caloris Basin, spans 1,550 kilometers — one of the largest in the Solar System. Formed by a colossal impact billions of years ago, it triggered volcanic eruptions that reshaped the surrounding terrain. On the opposite side of the planet lies the “weird terrain,” a chaotic jumble of hills and ridges likely created by shock waves from the same impact.

Volcanism not only shaped Mercury’s surface but may also have helped release volatile compounds, including water, from the planet’s mantle. Although Mercury’s atmosphere is now almost gone, these ancient outgassing events could have contributed to the polar ice we observe today.

MESSENGER and the Age of Discovery

Until recently, Mercury remained the least explored of the inner planets. The first close-up images came from NASA’s Mariner 10 in the 1970s, which flew by the planet three times but imaged only half its surface. For decades afterward, Mercury was a world half-seen, half-unknown.

That changed with MESSENGER (MErcury Surface, Space ENvironment, GEochemistry, and Ranging). This spacecraft orbited Mercury from 2011 to 2015, mapping the entire surface and revolutionizing our understanding. It revealed a world far more diverse and dynamic than expected — with volcanic plains, fault scarps, magnetic anomalies, and, of course, ice.

Among MESSENGER’s most surprising findings was the discovery of hollows — irregular, bright depressions unlike anything seen elsewhere. These features may form when volatile materials sublimate, leaving behind pits and cliffs. Their presence suggests that Mercury’s crust contains more volatile elements than scientists once thought, challenging assumptions about how close-in planets formed.

When MESSENGER finally ran out of fuel, it was deliberately crashed into Mercury’s surface in 2015, becoming part of the planet it had studied so closely. Its mission lives on through the data that continues to reshape planetary science.

BepiColombo: The Next Chapter

The story of Mercury is far from over. In 2018, the European Space Agency (ESA) and the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA) launched BepiColombo, a twin-spacecraft mission named after the Italian scientist Giuseppe “Bepi” Colombo, who first explained Mercury’s spin-orbit resonance.

BepiColombo carries two orbiters: ESA’s Mercury Planetary Orbiter and JAXA’s Mercury Magnetospheric Orbiter. Together, they will study the planet’s magnetic field, surface composition, and polar environment in unprecedented detail. Arriving in 2025, this mission promises to deepen our understanding of how Mercury formed, evolved, and continues to interact with the Sun.

Among its goals is to investigate the mysterious polar ice more closely, mapping its extent and composition. By understanding how this ice survives, scientists hope to refine models of planetary habitability and volatile delivery across the Solar System.

A Planet of Paradoxes

Mercury’s contradictions challenge our assumptions about how planets behave. It is the smallest, yet one of the densest; the hottest, yet home to frozen water; the least atmospheric, yet magnetically alive. It spins slowly but races around the Sun faster than any other world.

These paradoxes make Mercury an invaluable natural laboratory for studying planetary formation. Its giant metal core, volatile-rich crust, and preserved craters hold clues to processes that shaped not only Mercury but also Earth, Venus, and Mars. The discovery of ice in such an unlikely place underscores one of nature’s greatest lessons — that extremes often harbor coexistence, and that even the most inhospitable environments can surprise us with their complexity.

The Poetry of a Frozen World

Beyond its scientific intrigue, Mercury captures something deeply poetic. It is a world that embodies balance — between fire and frost, motion and stillness, death and persistence. To gaze upon its scarred face is to witness endurance itself: a planet battered, baked, and yet still holding on to its ancient ice.

In the gleam of its frozen craters, we glimpse our own origins — for the water that hides there may be the same water that once seeded Earth’s oceans. In this sense, Mercury’s ice connects us to the larger cosmic story of survival amid chaos.

The Messenger’s Legacy

As the closest planet to the Sun, Mercury exists on the frontier between order and destruction. It stands as both a survivor and a messenger, carrying within it the memory of how the inner Solar System came to be. The discovery of ice on such a world reminds us that the universe is full of paradoxes waiting to be understood — that even in places of searing light, shadows can preserve the past.

Mercury is not just a scorched rock orbiting the Sun; it is a monument to endurance and transformation. In its frozen poles lie the whispers of comets, the breath of ancient stars, and the legacy of cosmic time. And in every revolution around the Sun, it continues its eternal message: that creation and destruction are never separate, but two sides of the same cosmic truth.

In the end, Mercury — the planet closest to the Sun, yet full of ice — is a world that teaches us humility. It shows that the universe still holds surprises, that even the smallest worlds can harbor the greatest mysteries, and that the line between fire and ice is as thin and fragile as the balance that sustains us all.