At the edge of dawn, on a world closer to the Sun than any other, the horizon glows with a pale, silvery light. The ground shimmers under a skyless dome. Rocks burn, metal would melt, and silence reigns—absolute and eternal. This is Mercury, the smallest planet in the Solar System, a scorched and battered relic of the Sun’s creation. Yet within its extremes lies one of the strangest riddles in the cosmos: on Mercury, a single day—the time it takes for the Sun to rise and set—lasts almost as long as two of its years.

To understand Mercury is to step into a world where time itself feels distorted. The Sun climbs slowly into the black sky, halts, reverses, and then resumes its path, performing a dance of light never seen elsewhere. Day and night stretch beyond imagination, and heat and cold war in an endless cycle of extremes. It is a planet where time moves differently, both in perception and in the mechanics of celestial motion. Mercury’s day truly lasts a year—an astonishing cosmic coincidence born of physics, gravity, and the subtle harmonies of orbital resonance.

The Swift Messenger of the Gods

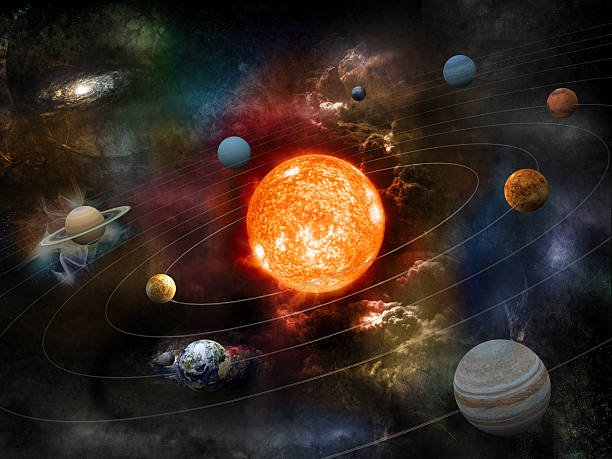

Mercury takes its name from the Roman god of speed, the winged messenger who moved swiftly between realms. The choice is fitting, for Mercury races around the Sun faster than any other planet—completing an orbit in just 88 Earth days. Yet despite this rapid journey through space, its rotation is surprisingly sluggish. It spins once on its axis every 59 Earth days.

This creates one of the most fascinating relationships in the Solar System: a 3:2 spin–orbit resonance. For every three rotations Mercury makes, it completes two orbits around the Sun. This resonance is no mere accident; it is the product of billions of years of gravitational tug-of-war between Mercury and the Sun. Over eons, solar tides slowed the planet’s spin until it became locked in this stable rhythm—a delicate balance between rotation and revolution.

The result is extraordinary. Because of this interplay, a single “solar day” on Mercury—the time from one sunrise to the next—lasts about 176 Earth days, or two Mercury years. In other words, if you stood on Mercury’s surface, you would see the Sun rise only once every two orbits. A year passes before the next dawn comes.

A Sky of Fire and Ice

The Mercurian day begins not with gentle light but with a blinding surge of radiance. As the Sun creeps above the horizon, it swells to more than twice the apparent size it has from Earth, flooding the barren landscape with fierce brilliance. Temperatures soar to 430 degrees Celsius (about 800 degrees Fahrenheit)—hot enough to melt lead. But with no atmosphere to trap heat, the night side plunges to -180 degrees Celsius (-290 degrees Fahrenheit). This dramatic contrast between fire and frost makes Mercury one of the most extreme environments in the Solar System.

The sky itself is pure black, even at noon. Without an atmosphere, there are no clouds, no scattering of sunlight, no blue. The stars remain visible even as the Sun glares overhead. Shadows are sharp-edged and absolute, etched in silver and darkness. It is a place of silence so complete that the concept of sound loses meaning—no wind, no rustle, only the slow ticking of cosmic time.

The Sun’s motion across the sky defies expectation. Because Mercury’s orbit is highly elliptical—more stretched out than that of any other planet—the speed of its motion around the Sun varies dramatically. Near perihelion, when Mercury is closest to the Sun, it races forward so fast that it temporarily outpaces its own rotation. To an observer standing on the surface, the Sun would appear to rise, pause, reverse direction for a time, and then resume its normal path. A sunrise that rewinds—a phenomenon found nowhere else in the cosmos.

The Shape of Time

Time on Mercury is not only strange—it is complex. There are three kinds of “days” that astronomers use to measure planetary motion: the sidereal day, the solar day, and the orbital period. Mercury’s unique 3:2 resonance makes these measurements deeply intertwined.

A sidereal day is the time it takes for a planet to rotate once relative to the background stars. For Mercury, that is about 59 Earth days. Its orbital period—the time it takes to complete one circuit around the Sun—is 88 Earth days. But because the planet rotates more slowly than it orbits, the Sun takes longer to return to the same position in the sky. This is the solar day—and on Mercury, it stretches to 176 Earth days, twice its orbital period.

This relationship produces an uncanny rhythm. If you lived on Mercury and stood at sunrise, you would watch the Sun climb, halt, and reverse as the planet sped through perihelion. Then, months later, you would watch it sink again below the horizon. Two Mercurian years would pass before another sunrise. The very concept of day and year, so simple on Earth, collapses into a strange symmetry on this little world.

The Making of a Planet of Paradoxes

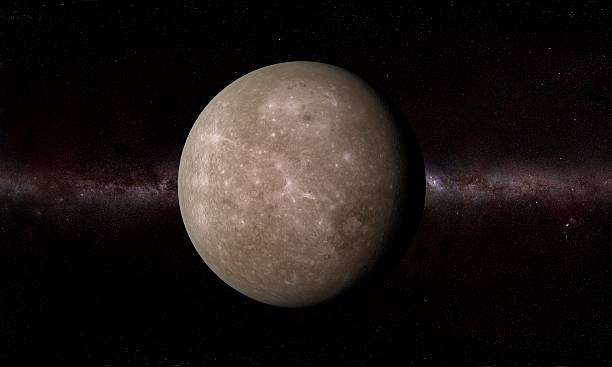

Mercury is both ancient and enigmatic—a world of paradoxes carved by cosmic violence. It is the smallest planet in the Solar System, barely larger than our Moon, yet it possesses an oversized metallic core that makes up nearly 85 percent of its radius. This dense interior gives Mercury one of the highest mean densities of any planet, second only to Earth.

How such a small world acquired so large a core remains a mystery. One theory suggests that Mercury was once much larger, but early in its history, a colossal impact stripped away much of its outer rock, leaving a metal-rich remnant. Another proposes that solar radiation during the Sun’s fiery youth vaporized lighter elements from the inner Solar System, leaving behind only dense materials like iron.

Whatever the cause, Mercury became a world of extremes—dense yet small, hot yet frozen, ancient yet restless. Its surface is a mosaic of craters, ridges, and plains, each marking an episode in its tumultuous past. The great Caloris Basin, a 1,550-kilometer-wide scar formed by a massive asteroid impact, stands as testimony to that violence. On the opposite side of the planet, shock waves from the collision created chaotic terrain—hills and valleys twisted as if melted and refrozen.

Mercury’s crust bears the wrinkles of time itself. As its metallic core cooled and contracted, the surface buckled, forming long cliffs called lobate scarps. Some of these stretch for hundreds of kilometers, towering like ancient walls over the plains. They reveal that the planet is still slowly shrinking—a process that continues even today.

The Dance of Resonance

The strange length of Mercury’s day is not random but the result of a cosmic balance. Over billions of years, the Sun’s gravity exerted tidal forces on the planet, gradually slowing its rotation. Initially, Mercury may have spun much faster—perhaps once every few hours. But tidal friction, the same process that locked Earth’s Moon to us, drained its rotational energy.

For a time, scientists believed Mercury was tidally locked to the Sun, always showing the same face. It was only in the 1960s, when radar observations revealed its true rotation rate, that the 3:2 resonance was discovered. This resonance is a stable equilibrium: when Mercury spins three times for every two orbits, the gravitational tugs from the Sun reinforce, rather than disrupt, its motion.

This delicate rhythm gives Mercury its slow, languid day—a day that lasts two of its years. No other planet in the Solar System exhibits such a relationship, making Mercury’s rotation one of the most elegant examples of orbital mechanics in nature.

The Heat of the Sun and the Cold of the Shadows

If you could stand on Mercury’s surface, time would not only move strangely—it would feel strange. During the long day, temperatures soar high enough to vaporize metal, yet with no atmosphere to conduct heat, even a few steps into shadow could plunge you into bitter cold.

The lack of atmosphere also means there are no winds, no clouds, and no erosion in the familiar sense. The landscape remains nearly frozen in time, its craters and plains preserved for billions of years. The only change comes from meteorite impacts and the relentless bombardment of solar radiation.

Yet not all parts of Mercury bake in sunlight. At its poles lie deep craters so shadowed that sunlight has never reached them. In these eternal dark zones, temperatures stay below -170°C, cold enough to trap volatile substances. Radar observations from Earth and spacecraft like MESSENGER have revealed deposits of water ice within these craters—gleaming relics of comets or perhaps of ancient volcanic gases. The hottest world near the Sun, paradoxically, harbors ice at its frozen poles.

The Elusive Atmosphere

Mercury’s gravity is too weak to hold a substantial atmosphere, and its proximity to the Sun constantly strips away gases. Instead, it possesses a tenuous exosphere—an ultra-thin veil of atoms blasted from its surface by solar wind and micrometeorites. This exosphere is composed mainly of oxygen, sodium, hydrogen, helium, and potassium, all of which escape rapidly into space.

Although almost imperceptible, this ghostly envelope gives Mercury a faint glow. Sodium atoms, excited by sunlight, produce a subtle yellow emission that can be detected by telescopes. The exosphere also forms long tails of atoms trailing behind the planet, reminiscent of a comet’s tail, visible in ultraviolet light.

Mercury’s surface is also continually reshaped by solar wind—streams of charged particles from the Sun that carve patterns in its magnetic field. Despite its small size, Mercury has an active global magnetic field, about one percent as strong as Earth’s, generated by a partially molten core. This magnetic shield deflects some solar particles, creating miniature auroras that flicker faintly across its skyless poles.

A Planet of Long Shadows

Because Mercury’s day lasts so long, its shadows move with glacial slowness. A rock might cast the same shadow for weeks before the Sun’s motion shifts it noticeably. This slow drift of light and shadow creates an uncanny sense of suspended time.

If an astronaut stood near the equator, the Sun’s rise would be an almost imperceptible event. Days would pass before it cleared the horizon, climbing higher each week until the long noon, when the Sun seems to stop, reverse, and pause once again. Night would return just as slowly, creeping across the land like a tide of darkness.

Under the faint starlight of the Mercurian night, Earth would sometimes be visible as a bright morning or evening star, casting a steady blue glow—a reminder of the world from which time itself once seemed simpler.

The Exploration of Mercury

For centuries, Mercury was the most elusive of the planets. Its closeness to the Sun made it difficult to observe, always hidden in twilight glare. Ancient astronomers thought it was two separate objects—Hermes, the morning star, and Apollo, the evening star—before realizing they were one.

Modern exploration of Mercury began only in the space age. NASA’s Mariner 10 mission, launched in 1973, became the first spacecraft to visit Mercury. It revealed a cratered, airless world resembling the Moon, but with hints of volcanic plains and magnetic activity. Because of its trajectory, Mariner 10 only photographed about 45 percent of the planet’s surface, leaving much of Mercury shrouded in mystery.

Three decades later, the MESSENGER spacecraft transformed our understanding. Entering orbit in 2011, it mapped the entire surface, analyzed its chemistry, and discovered water ice at the poles. It found evidence of volcanic vents and tectonic features that hinted at Mercury’s shrinking interior. MESSENGER also revealed that Mercury’s magnetic field is offset from its center—an asymmetry that may offer clues to the dynamics of its molten core.

In 2018, the joint European–Japanese mission BepiColombo began its journey to Mercury. Set to arrive in the mid-2020s, it carries two orbiters designed to study the planet’s magnetosphere, surface, and composition in greater detail than ever before. Each mission brings us closer to understanding how this small, searing world defies expectations and endures.

The Relativity of Time

On Mercury, time does not simply stretch—it bends under the weight of proximity to the Sun. According to Einstein’s general theory of relativity, time runs slightly slower in stronger gravitational fields. Because Mercury is so close to the Sun, clocks there would tick more slowly than on Earth, by about 1.6 milliseconds per day. Though imperceptible to the human mind, this difference reminds us that even time itself is shaped by gravity.

In a poetic sense, Mercury exists in a different rhythm of time—one molded by both celestial mechanics and relativity. Its long days, short years, and altered flow of seconds make it a world where human intuition fails. The planet becomes a natural laboratory for understanding not only orbital dynamics but also the profound connection between motion, mass, and the fabric of spacetime.

Mercury’s Role in Cosmic History

Mercury is not just an isolated curiosity—it is a relic of the Solar System’s birth. Its composition and orbit preserve clues about the violent processes that shaped the inner planets. By studying Mercury, scientists can piece together the story of how matter condensed from the solar nebula, how collisions sculpted worlds, and how proximity to the Sun influenced planetary evolution.

Its dense core and depleted silicate mantle tell of extreme conditions. Its scarred surface records the bombardment that marked the Solar System’s youth. Even its peculiar orbit—tilted and eccentric—hints at gravitational encounters with Venus and Jupiter long ago. Mercury is the fossil of planetary formation, a survivor from a time when the Solar System was a chaotic sea of collisions and migrations.

The Paradox of Permanence

For all its extremes, Mercury remains strangely constant. Its features endure across eons, unaltered by wind or rain. A crater that formed a billion years ago looks as fresh as one formed yesterday. Time, in a geological sense, moves slowly here. The planet’s very stillness becomes a kind of endurance—a defiance of entropy in a cosmos of change.

And yet, Mercury is not entirely silent. It quivers with occasional seismic tremors, contracts with the slow cooling of its core, and interacts with the solar wind in a dance of magnetic energy. Beneath its apparent stillness, it is alive with the quiet motions of physics, the slow ticking of cosmic time.

The Human Perspective

For humans, Mercury is both unreachable and profoundly symbolic. It reminds us of speed and stillness, heat and cold, motion and time. It embodies the paradoxes that define existence: a planet racing around the Sun yet turning slowly, a world both ancient and ever-new.

Were we to stand there, watching a sunrise that takes weeks to unfold, we might feel the enormity of time differently. A single day on Mercury would span nearly half a year on Earth. Birth, aging, and death—all the measures of human life—would stretch and warp in the stillness of that alien dawn.

Perhaps that is Mercury’s greatest lesson: that time, which we treat as absolute, is a construct of motion and perspective. The universe does not keep time for us; we impose meaning upon its rhythms. Mercury simply moves, turning and orbiting in its silent, perfect cadence.

The Future of Exploration

In the coming decades, Mercury will continue to draw the curiosity of explorers and scientists alike. Missions such as BepiColombo aim not only to study its surface but to understand how planets form and evolve near their stars—knowledge that extends far beyond our Solar System to the thousands of exoplanets discovered around distant suns.

The data Mercury provides could help us decipher the behavior of rocky worlds orbiting close to their stars—so-called “super-Mercuries” that burn under relentless light. By studying this small, resilient planet, we glimpse the possible futures of others. Mercury thus becomes a key to understanding both our cosmic past and the diversity of worlds beyond.

The Planet Where Time Stands Still

In the end, Mercury remains one of the Solar System’s most poetic enigmas—a world where time folds upon itself, where days outlast years, where sunlight lingers as if reluctant to leave. Its rhythms challenge our sense of normalcy, revealing how the universe shapes time differently for every world.

As the Sun burns overhead in its immense and patient arc, Mercury endures, locked in its eternal dance. Two years pass between dawns, yet nothing truly changes. The craters remain, the rocks shimmer, and the shadows move so slowly that a human life could fit between sunrise and sunset.

Mercury teaches us humility in the face of cosmic scale. It shows that time is not a universal constant but a rhythm played differently on every world. On this small, swift, and strangely slow planet, a day that lasts a year is not a paradox—it is a reminder that the universe moves according to laws both simple and sublime.

Mercury, the swift messenger of the gods, carries not only the story of motion but the story of time itself—a tale of a world where the Sun rises once every two years and where the very concept of day and night dissolves into the endless music of the cosmos.