In the boundless darkness of the cosmos, where countless worlds spin in silence around distant suns, there are some planets that defy reason itself. These are the cosmic enigmas—the worlds that by all logic should not exist, yet do. They bend the rules of physics, challenge the limits of formation, and force astronomers to rethink what they know about the universe. Among these strange orphans of creation lies a tale both humbling and awe-inspiring: the story of a planet that should never have been.

The story begins, as most cosmic tales do, with a flicker of light detected from afar. A star, faint and unassuming, sits hundreds of light-years away, and yet around it orbits a giant—a massive world that defies every prediction of planetary science. Its mass, composition, and location all scream impossibility. How could such a planet form in such a place? What process could give birth to something so improbable?

This is not just a single planet’s story—it is a reflection of our evolving understanding of the universe. It speaks of how much we still do not know about the birth of worlds, and how the cosmos delights in defying expectations. It reminds us that even our most elegant theories are but fragile scaffolds built against the vast unknown.

The Search for Other Worlds

For most of human history, Earth was the only known planet in the universe. The stars were fixed lights, eternal and distant, and the Sun and Moon were gods. But in the late 20th century, something extraordinary happened: we began to find planets orbiting other stars—exoplanets.

The first confirmed detection came in 1992, when astronomers Aleksander Wolszczan and Dale Frail discovered two planets orbiting a pulsar—a dead, rapidly spinning star that emits beams of radiation like a cosmic lighthouse. These worlds, scorched by deadly radiation, were utterly alien. Yet their existence shattered the long-held assumption that planets could only form around calm, stable stars like the Sun.

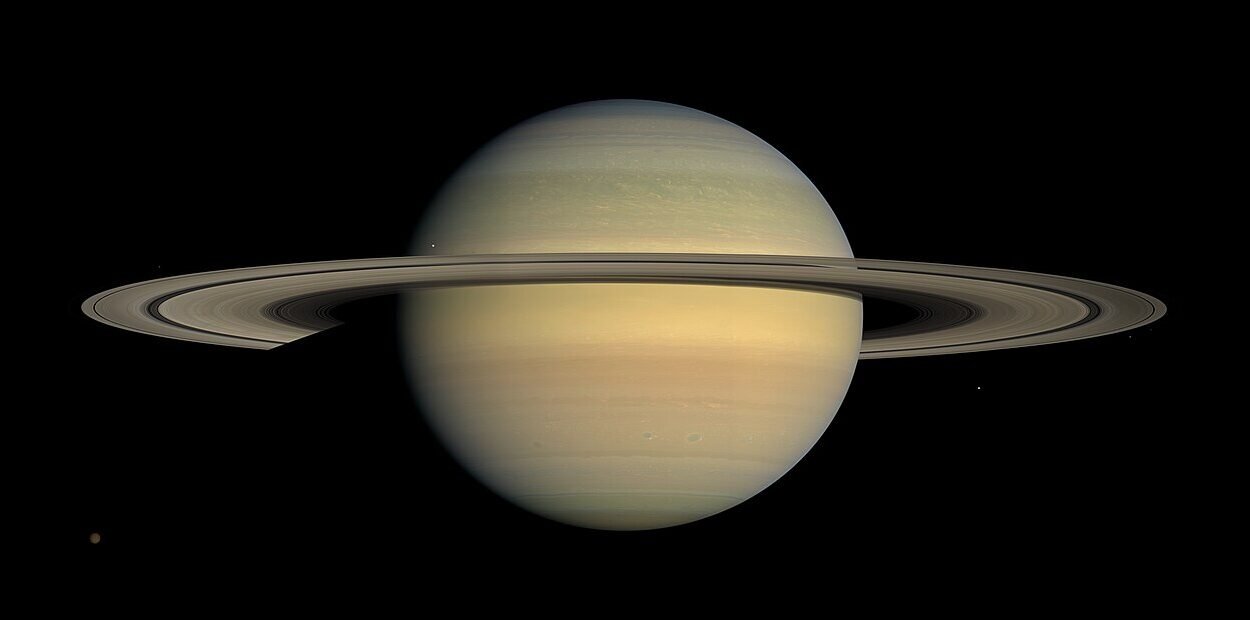

Three years later, a new shock arrived. Michel Mayor and Didier Queloz detected a giant planet orbiting the Sun-like star 51 Pegasi. This planet, named 51 Pegasi b, was unlike anything seen before—a “hot Jupiter,” a gas giant larger than Jupiter but orbiting closer to its star than Mercury does to the Sun. According to existing theories of planetary formation, such a planet should not exist. Gas giants were thought to form far from their stars, beyond the so-called “frost line,” where ices could condense to form massive cores. Yet here was a giant, roasting at a temperature of over 1000°C, circling its sun every four days.

From that moment, the universe began revealing its secrets with dizzying speed. Astronomers soon discovered thousands of exoplanets, each one stranger than the last. Super-Earths larger than our own planet but smaller than Neptune. Ocean worlds with global seas. Planets orbiting twin suns like Tatooine. And even “rogue planets,” drifting freely through space without a star to call home. But among all these wonders, some stood out for their sheer defiance of logic—the planets that, according to our best understanding, simply should not exist.

The Impossible Giant

Imagine a world so large that it dwarfs Jupiter, yet orbiting a star barely massive enough to sustain fusion. This was the puzzle astronomers faced when they discovered planets like HAT-P-2b, WASP-18b, and the aptly named “Planet That Shouldn’t Exist”—a nickname often applied to systems where theory and observation collide.

One of the most striking examples was a planet known as Kepler-88 d, a gas giant several times the mass of Jupiter, orbiting a relatively modest star. The problem was not its existence alone—it was its location. According to prevailing models, such massive planets should form far from their stars, where cold temperatures allow icy materials to build planetary cores. Yet Kepler-88 d and its kind orbit at distances where any such materials would have evaporated long before a planet could take shape.

Astronomers soon realized that nature had outsmarted them again. These “hot Jupiters” and “warm giants” might not have formed where they are now. Instead, they could have been born in the outer reaches of their systems and migrated inward, pulled by interactions with the disk of gas and dust that surrounded their young stars. But this migration raised another question: why didn’t these massive worlds crash into their stars or fling smaller planets away? The answer, still under debate, lies in the subtle ballet of gravity—a cosmic dance where even the slightest imbalance can reshape entire solar systems.

A Planet Around a Pulsar

Among the strangest of all planetary systems is one that defies not only formation theory but survival itself: the planets around the pulsar PSR B1257+12. When the discovery was first announced, many astronomers doubted it could be true. Pulsars are the remnants of massive stars that have exploded in supernovae, leaving behind dense neutron stars spinning at incredible speeds. The shockwaves and radiation from such explosions are so violent that any nearby planets should be obliterated. And yet, orbiting PSR B1257+12 are at least three planets—dead worlds circling a dead star.

How could planets exist around something so destructive? The leading explanation is that these worlds formed after the supernova, from the debris left behind. As material from the explosion fell back toward the pulsar, it may have formed a disk—similar to the one from which ordinary planets emerge. From that disk, new planets coalesced, phoenix-like, from the ashes of their parent star. These are worlds literally born from death, a testament to the universe’s capacity for regeneration.

The pulsar planets forced astronomers to expand their imagination. They showed that planet formation could occur in environments once thought impossible, even in the aftermath of cosmic catastrophe. The universe, it seemed, was far more inventive than human theory could predict.

The Case of the Wandering Worlds

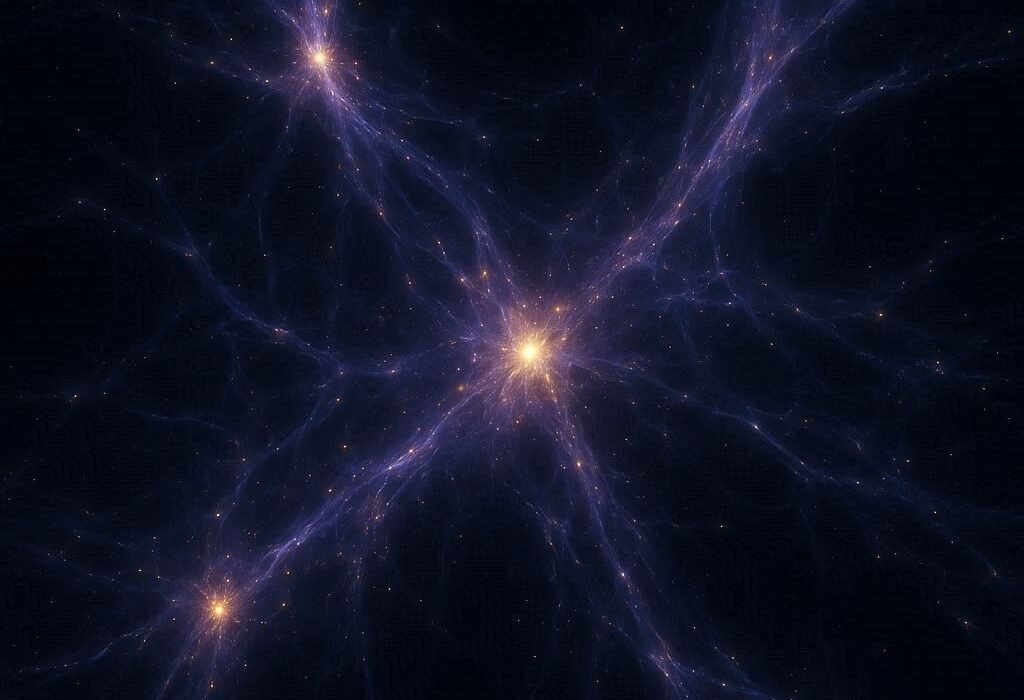

If some planets form too close to their stars, others wander too far—or escape entirely. Over the past two decades, astronomers have discovered “rogue planets,” worlds that drift freely through interstellar space, unbound to any star. Some are massive like Jupiter, others small like Earth. They float in the darkness, frozen and silent, yet still very much alive in the cosmic sense.

These wandering worlds challenge our understanding of planetary birth and death. Were they ejected from their home systems by gravitational chaos? Or did they form independently, like miniature stars that never ignited? Observations suggest that both scenarios may be true. Some rogue planets may be the victims of violent planetary dynamics, thrown out by larger neighbors. Others may have condensed directly from collapsing gas clouds, blurring the line between planets and brown dwarfs.

The existence of billions of rogue planets across the Milky Way reveals another truth: planetary systems are not stable, orderly families—they are dynamic, evolving ecosystems, shaped by collisions, migrations, and expulsions. The universe builds worlds not with precision, but with creative chaos.

The World That Should Have Frozen

Another planetary paradox emerges in the form of “hot Neptunes”—planets roughly the size of Neptune but orbiting perilously close to their stars. According to classical models, such worlds should have lost their atmospheres long ago. The intense stellar radiation at those distances should strip away hydrogen and helium, leaving behind only a rocky core. Yet astronomers have found many of these planets still enveloped in thick gaseous atmospheres, defying both physics and logic.

One particularly puzzling case is Gliese 436 b, a Neptune-sized planet orbiting a red dwarf star just 33 light-years from Earth. Its temperature exceeds 700°C, hot enough to melt lead, and yet it retains a vast atmosphere of hydrogen and helium. Even more astonishingly, Gliese 436 b seems to have an orbit that is not circular but elongated—an eccentricity that should have been smoothed out long ago by tidal forces. Something, perhaps an unseen companion planet, continues to tug on it, maintaining its strange, fiery path.

To explain such worlds, astronomers have proposed a range of exotic possibilities: magnetic shielding, atmospheric replenishment, or hidden layers of exotic ices that trap gases against escape. Each new observation adds a piece to the puzzle, but the full picture remains elusive.

The Planets That Outlive Their Suns

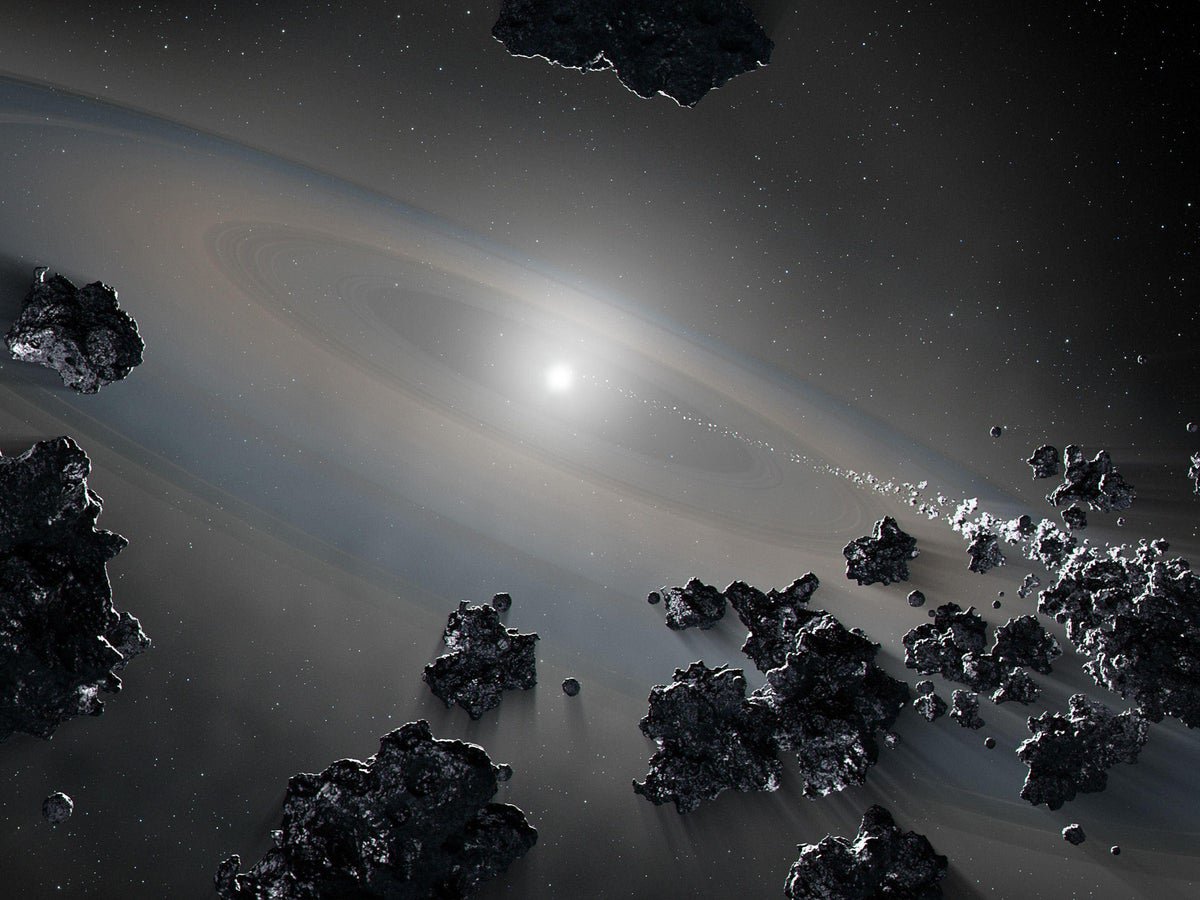

The universe also holds planets that have survived the death of their stars. Around white dwarfs—the dense remnants of Sun-like stars—astronomers have found planets and debris disks that shouldn’t exist. When a star becomes a red giant, it expands to engulf its inner planets, scorching or destroying them. And yet, worlds have been found orbiting within a few million kilometers of white dwarfs, impossibly close to the remnants of their stellar parents.

One such system, WD 1856+534, hosts a Jupiter-sized planet that circles its white dwarf every 34 hours. The planet’s proximity suggests it must have migrated inward after the star’s death, perhaps drawn by gravitational interactions with other bodies. Its survival challenges every model of stellar evolution. The fact that it still exists—intact and stable—demonstrates that planetary systems can endure even the violent death throes of their stars.

These discoveries reveal that planets are not passive bystanders in cosmic evolution. They are resilient survivors, adapting and enduring in ways we are only beginning to understand. Even when their suns die, they find new orbits, new equilibria, and sometimes, new beginnings.

The Chemistry of Impossibility

Beyond questions of size and orbit, some planets defy expectations in composition. Take the so-called “carbon planets,” hypothetical worlds rich in carbon compounds rather than silicates and oxygen like Earth. In systems where carbon is more abundant than oxygen, planets could form with surfaces of graphite, carbides, and even diamonds. Though no definitive example has yet been confirmed, candidates like 55 Cancri e—an ultra-hot super-Earth with a dense, possibly carbon-rich interior—suggest that such exotic worlds may exist.

Equally intriguing are “lava worlds” such as K2-141b, where the dayside is an ocean of molten rock, and the atmosphere is made of vaporized minerals that rain down as stone. Others, like GJ 1214 b, may be “water worlds,” with deep global oceans and dense steam atmospheres. Each of these planetary types expands the boundaries of what a planet can be.

The diversity of these worlds, some scorched, others frozen, some bursting with chemicals never found on Earth, shows that the universe’s creativity knows no bounds. It builds planets from whatever materials are available, crafting endless variations on the theme of existence.

The Fragility of Theory

When astronomers first devised models of planetary formation, they imagined something orderly: dust grains coalescing into pebbles, pebbles into rocks, rocks into planets. The process seemed simple, elegant, inevitable. But the discovery of planets that shouldn’t exist has revealed a deeper truth: the cosmos is not governed by simplicity. It is a theater of chaos and chance.

Planetary systems form amid turbulence—gas disks that swirl, collide, and fragment. Planets migrate, crash, and merge. Some are born too close to their stars, some too far. Others arise from the ashes of destruction. The “impossible” planets are not exceptions but reminders that our theories, while beautiful, are approximations of reality. Nature is under no obligation to follow human logic.

This humility is central to science itself. Every “impossible” planet discovered expands our understanding of what is possible. Each one forces us to rewrite the story of planetary genesis, to widen our definitions of habitability and stability, and to admit that we are only beginning to glimpse the true diversity of worlds in the cosmos.

The Planet That Changed Everything

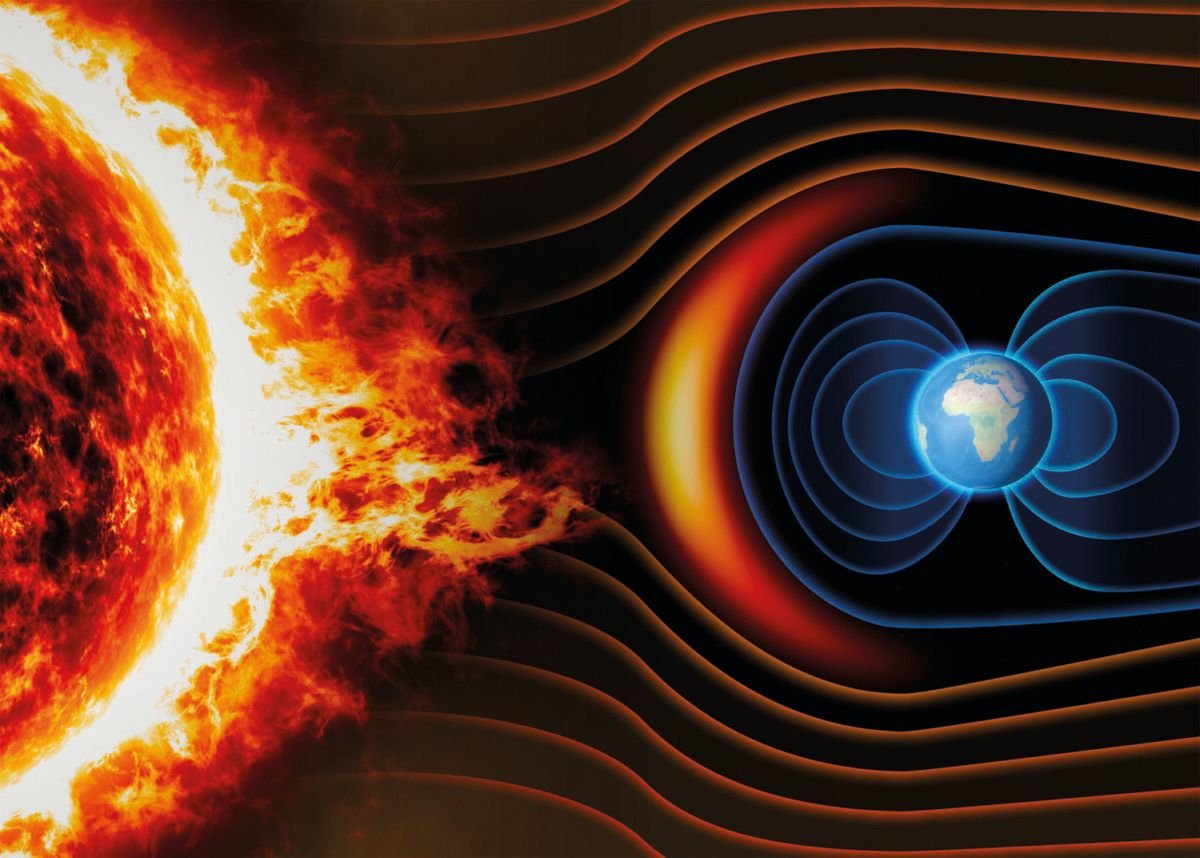

In 2016, astronomers announced the discovery of Proxima Centauri b, a potentially Earth-sized planet orbiting the nearest star to the Sun. Its presence was surprising for different reasons—not because it defied physics, but because it revealed how common planets might be even around the most unlikely stars. Proxima Centauri is a red dwarf, prone to violent flares and radiation bursts. Yet it hosts a planet within its habitable zone, where liquid water might exist.

This discovery reframed the question entirely. The universe is not merely home to planets that shouldn’t exist—it is teeming with worlds that do exist, against all odds. Life, too, may be more resilient than we imagine, able to find footholds even in the harshest environments.

Proxima Centauri b became a symbol of possibility—a reminder that the line between the impossible and the real is often drawn by the limits of our imagination.

Lessons from the Impossible

The story of the planet that shouldn’t exist is, ultimately, the story of science itself—a narrative of wonder, confusion, and discovery. Each contradiction, each paradox, is an invitation to look deeper. When astronomers find a world that defies theory, they do not discard the mystery; they embrace it, knowing that in the unknown lies the seed of progress.

These planets remind us that the universe is not a machine of rigid laws but a living, evolving cosmos. It builds, destroys, and rebuilds with boundless creativity. It makes stars that die and still give birth, planets that survive infernos, and systems that balance on the edge of chaos.

In their defiance, these worlds echo something profoundly human—the instinct to endure, to exist against all odds, to persist when logic says we should not.

A Universe That Surprises

When we gaze into the night sky, we are not just looking at distant points of light—we are looking into an infinite laboratory of creation. Every star may host planets; every planet may tell a different story. Some worlds will fit our expectations; others will rewrite them entirely.

The planet that shouldn’t exist is not just an anomaly—it is a messenger. It tells us that our universe is far richer and more mysterious than we can yet comprehend. It challenges us to let go of certainty, to accept that mystery is not the enemy of knowledge but its driving force.

For in every impossible world, there is a whisper from the cosmos: You do not yet know everything. Keep searching.

The Infinite Improbability of Existence

In the end, perhaps every planet “shouldn’t exist” in the strictest sense. The odds of any one world forming exactly as it did—of atoms coalescing, of orbits stabilizing, of systems surviving billions of years—are infinitesimal. Yet they do exist, just as we do.

Our own Earth is, in many ways, the ultimate impossible planet. Formed from chaos, tempered by fire, and blessed by balance, it harbors life in a universe that seems overwhelmingly hostile. Like those distant, improbable worlds, we too are the products of cosmic accidents that somehow led to harmony.

To study the planets that shouldn’t exist is to understand our own unlikely place in the universe. It is to see that impossibility itself is part of the fabric of creation—that the cosmos thrives on surprise.

The Enduring Wonder

There will always be another planet that defies our theories, another discovery that reshapes our understanding. The universe, vast and patient, will never run out of mysteries. And perhaps that is its greatest gift to us—not the certainty of knowledge, but the endless invitation to seek, to question, and to marvel.

Somewhere out there, another world circles a distant sun, its existence waiting to astonish us once again. A planet that, by every law we know, should not be—but is.

And that, more than anything, is the story of the cosmos itself: a universe of impossibilities made real, where even the unthinkable becomes true, and where every unlikely world is a reminder of the boundless creativity that shaped us all.