Among all the planets in our Solar System, Venus stands as one of the most captivating and confounding. Draped in thick clouds and shining brilliantly in Earth’s skies, it has long been known as both the “Morning Star” and the “Evening Star.” To the naked eye, Venus appears serene and radiant—a celestial pearl glowing in the dawn or dusk. Yet this beauty conceals an inferno. Beneath its shrouded atmosphere lies a world of crushing pressure, toxic gases, and temperatures hot enough to melt lead.

For much of history, Venus was imagined as Earth’s twin—a sister planet of similar size and composition, orbiting just a little closer to the Sun. Early astronomers speculated that beneath those clouds might lie lush jungles or warm oceans. But when space probes finally peered through its veil, the dream dissolved into horror. The surface of Venus proved to be one of the most hostile places imaginable, with temperatures around 465°C (869°F), atmospheric pressures 92 times greater than Earth’s, and a suffocating blanket of carbon dioxide laced with sulfuric acid.

Yet even amid this desolation, one question has refused to die: Could life, somehow, find a way to survive in the atmosphere of Venus? In recent years, new scientific discoveries have breathed fresh life into this idea. While its surface remains a hellish wasteland, its upper atmosphere—about 50 to 60 kilometers above the ground—offers surprisingly temperate conditions. Here, in a realm of clouds and chemistry, lies one of the most intriguing frontiers in the search for extraterrestrial life.

The Face of a Fiery Planet

To understand the possibility of life on Venus, one must first confront the nature of the planet itself. Venus is roughly the same size as Earth, with a diameter of about 12,100 kilometers, and it orbits the Sun at about 70 percent of Earth’s distance. Its composition is similar—rocky, with a metallic core—but the similarities end there.

The Venusian atmosphere is a suffocating ocean of carbon dioxide, with traces of nitrogen, sulfur dioxide, and other gases. Its dense cloud layers reflect most sunlight, making Venus the brightest natural object in the sky after the Sun and Moon. But beneath those clouds, the greenhouse effect rages unchecked. Sunlight penetrates the atmosphere, heating the surface, but the thick blanket of carbon dioxide traps the heat, allowing almost none to escape. The result is a runaway greenhouse effect—a planetary furnace that transformed what may once have been an ocean world into a desolate desert of fire.

Winds whip around the planet at speeds exceeding 300 kilometers per hour in the upper atmosphere, while the surface rotates slowly beneath them. A day on Venus—the time it takes for one full rotation—lasts 243 Earth days, longer than its year, which is only 225 Earth days. To make matters stranger, Venus spins in the opposite direction from most planets, meaning the Sun rises in the west and sets in the east.

Radar images from missions like NASA’s Magellan have revealed a surface scarred by volcanoes, mountains, and vast plains of lava. Over 80 percent of Venus’ terrain appears volcanic, suggesting that immense eruptions once reshaped its crust. Some scientists suspect that volcanic activity may still persist, releasing gases into the atmosphere and sustaining the planet’s sulfur-rich clouds.

It is within this complex, violent environment that the question of life must be asked—not on the infernal ground, but in the strange, drifting world above it.

A History of Hope and Disillusion

Before the Space Age, Venus was often imagined as a verdant paradise—a steamy world covered in oceans and tropical forests. Because its clouds hid the surface from view, speculation ran wild. In the early 20th century, astronomers such as Percival Lowell envisioned a swampy world teeming with primitive life. Science fiction authors wrote of amphibious Venusians, floating cities, and alien jungles bathed in perpetual twilight.

Those dreams began to crumble in the 1960s when the first spacecraft reached Venus. The Soviet Venera probes, followed by NASA’s Mariner missions, revealed an environment far beyond anything humans could endure. In 1967, Venera 4 became the first probe to directly sample another planet’s atmosphere, discovering the overwhelming carbon dioxide content and confirming the extreme pressure. Venera 7, in 1970, achieved a milestone by transmitting data from the surface itself—though it lasted only 23 minutes before succumbing to the heat.

The evidence was undeniable: Venus’ surface was utterly inhospitable. The temperatures and pressures destroyed electronics, melted metal, and crushed landers like tin cans. No liquid water could exist, and the atmosphere was saturated with corrosive acid droplets. For decades, the idea of life on Venus seemed dead.

And yet, as scientists studied the planet’s atmosphere more closely, a new possibility emerged. Not on the surface—but high above it—conditions might be far more forgiving. Could the clouds of Venus harbor something extraordinary?

The Temperate Zone in the Clouds

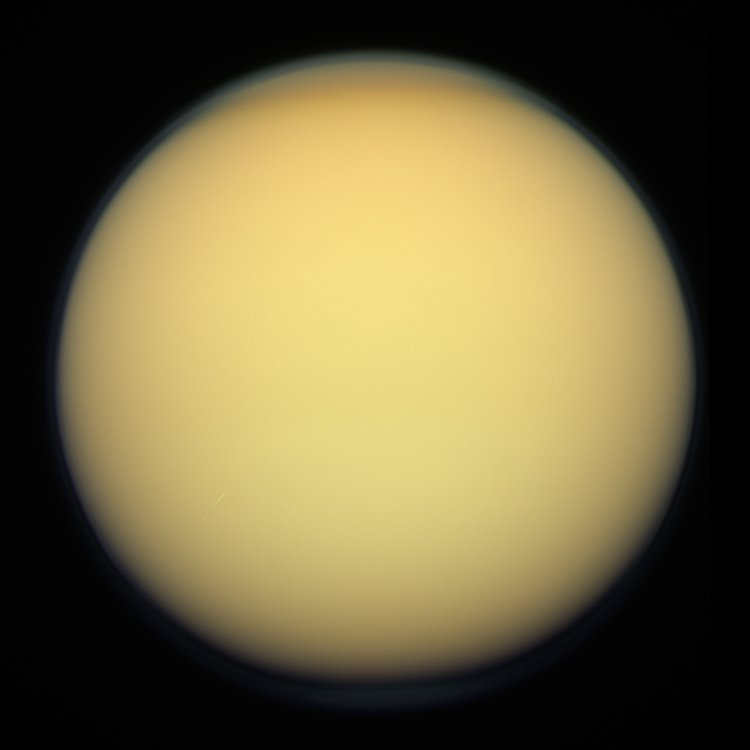

Rising through the suffocating layers of Venus’ atmosphere, one eventually reaches a zone between 50 and 60 kilometers above the surface where conditions change dramatically. Here, temperatures range from 20°C to 60°C—roughly comparable to the range experienced on Earth. Pressure in this region also drops to near-Earth levels, around one atmosphere. In this thin sliver of the Venusian sky, life as we know it might, at least theoretically, find refuge.

But this habitable zone is far from benign. The atmosphere is composed mostly of carbon dioxide, with very little water vapor and an abundance of sulfuric acid. The clouds are made not of water, but of droplets containing concentrated sulfuric acid—so corrosive that they can dissolve metal and destroy organic molecules. Radiation from the Sun bombards this layer continuously, and oxygen—the molecule essential for most known forms of life—is virtually absent.

Still, Earth’s biosphere offers striking examples of resilience. Extremophiles—microbes that thrive in the harshest environments—flourish in places once thought lifeless. On Earth, we find life in boiling hot springs, deep-sea hydrothermal vents, radioactive waste, and acid-soaked mine waters. There are bacteria and fungi capable of surviving in acid environments with pH levels below 1, comparable to the conditions in Venus’ clouds. Some microorganisms even float through Earth’s upper atmosphere, enduring high radiation and desiccation.

Could similar microbes exist, or have once existed, in the skies of Venus?

The Question of Phosphine

In 2020, the scientific world was electrified by an announcement that reignited the debate over life on Venus. A team of astronomers using the James Clerk Maxwell Telescope in Hawaii and the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA) in Chile reported detecting traces of phosphine gas (PH₃) in Venus’ atmosphere.

On Earth, phosphine is produced primarily by biological processes—specifically by microbes that thrive in oxygen-poor environments. It can also be created artificially in laboratories, but the natural geochemical processes that generate it are rare and inefficient. The detection of phosphine, therefore, was hailed as a possible biosignature—a chemical clue hinting at microbial life.

The claim provoked immediate excitement and skepticism. If true, it would represent one of the most profound discoveries in history: evidence that life may exist beyond Earth. However, subsequent analyses raised doubts. Some studies failed to confirm the phosphine signal, suggesting that the initial detection might have been an artifact of data processing. Others proposed alternative explanations, such as volcanic or photochemical reactions that could produce phosphine abiotically.

Despite the controversy, the incident revived serious scientific interest in Venus. Even if the phosphine detection proves erroneous, the mere possibility underscores how little we truly know about the planet’s chemistry. The episode also demonstrated the need for direct exploration—spacecraft capable of sampling the atmosphere in situ, to determine what really lingers within those golden clouds.

Life in the Clouds: A Theoretical Possibility

To imagine life in Venus’ atmosphere, we must abandon familiar concepts of biospheres and ecosystems. On the surface, conditions are fatal. But within the temperate cloud layer, one can envision microbial life adapted to extraordinary extremes.

The concept is not entirely speculative. In 1967, even before the Venera missions, Carl Sagan and Harold Morowitz proposed that microbial life might float in Venus’ clouds. They reasoned that microorganisms could exist as tiny droplets or spores, suspended by updrafts, feeding on sunlight and atmospheric chemicals. Over time, they could evolve to survive in acidic conditions by forming protective coatings or by neutralizing acid internally.

In this hypothetical ecosystem, microbes might use sunlight for photosynthesis, or derive energy from chemical reactions involving sulfur compounds—similar to Earth’s sulfur-oxidizing bacteria. These life forms could absorb carbon dioxide and other trace gases, living in a delicate balance between gravity pulling them downward and atmospheric currents lifting them up.

Venus’ atmosphere contains numerous reactive chemicals—sulfur dioxide, water vapor, carbon monoxide, and traces of chlorine and iron. Such a chemical soup could potentially support energy cycles, even if alien to terrestrial life. Some models suggest that non-water-based life might exploit sulfuric acid itself as a solvent, though this remains highly speculative.

If such organisms exist, they would represent an entirely new domain of biology—life not of Earth, yet not completely disconnected from it. For if Venus once had oceans and milder climates, as many believe, life could have originated on its surface billions of years ago and retreated upward as the planet grew hotter.

The Ancient Past: Oceans and Loss

Long before Venus became the inferno we see today, it may have been far more Earth-like. Climate models suggest that for the first billion years of its history, Venus could have hosted shallow oceans and a moderate climate. During this period, solar radiation was weaker, and the atmosphere may have contained less carbon dioxide.

If true, this means Venus might once have been habitable—perhaps even inhabited. But something went terribly wrong. As the Sun brightened over time, water in Venus’ oceans began to evaporate. The increasing humidity amplified the greenhouse effect, trapping more heat and accelerating evaporation in a feedback loop.

Ultraviolet radiation from the Sun split the water vapor into hydrogen and oxygen. The lightweight hydrogen escaped into space, while the oxygen reacted with carbon and sulfur to form new compounds. Gradually, Venus lost its oceans entirely, leaving behind a desert world smothered by carbon dioxide and sulfur dioxide.

This transformation may have occurred over hundreds of millions of years—a slow planetary death that turned a once-temperate world into a furnace. If microbial life had arisen during Venus’ early period of habitability, it might have found refuge in the atmosphere as the surface became uninhabitable. There, protected within droplets or aerosols, it could have endured for eons.

The possibility that life began on Venus and adapted to its changing environment connects to a broader question: Is life a rare fluke, or an inevitable outcome of planetary evolution? If Venus once nurtured life, its fate becomes both a warning and a revelation—a glimpse into Earth’s potential future if our own greenhouse effect runs unchecked.

Lessons from Extremophiles

The resilience of life on Earth provides reason for optimism—and caution. On our planet, extremophiles have been found in environments that mimic aspects of Venus’ atmosphere.

Acidophilic bacteria thrive in sulfuric acid mines, withstanding pH levels below 1. Thermophiles endure scalding temperatures above 100°C in hydrothermal vents. In the upper atmosphere, microbes have been found living within water droplets at altitudes up to 40 kilometers, surviving low pressure, desiccation, and radiation.

These examples reveal that life can adapt to chemical and physical extremes once thought impossible. They also broaden our definition of habitability. Life does not require Earth-like comfort—it requires stability, energy, and a solvent to enable biochemical reactions.

However, there are limits. Venus’ clouds are extraordinarily dry, containing only about 0.003 percent water—far less than even Earth’s driest deserts. Without water, known biological processes cannot function. Moreover, the concentration of sulfuric acid in Venus’ clouds approaches 90 percent, which would destroy organic molecules unless they possess protective adaptations unknown in any terrestrial organism.

To survive in such an environment, hypothetical Venusian microbes would need extraordinary chemistry—perhaps using acid-resistant cell walls, non-water-based solvents, or alternative genetic molecules. While this may sound improbable, the diversity of life on Earth suggests that evolution is a master of invention. If life can exist in boiling acid lakes or radioactive waste, perhaps it can find a way in the clouds of Venus.

The Chemistry of Survival

What would life on Venus use for energy? On Earth, life relies primarily on sunlight or chemical gradients—differences in energy between compounds such as hydrogen, oxygen, sulfur, or iron. In Venus’ atmosphere, sunlight is abundant, but ultraviolet radiation is intense, and the available chemicals differ.

Sulfur compounds dominate the Venusian atmosphere. Microbes could, in theory, derive energy from converting sulfur dioxide to sulfur or sulfate, much as certain Earth bacteria do. Another potential pathway involves reactions between carbon monoxide and sulfuric acid, or between trace hydrogen and carbon dioxide. These energy sources are speculative but chemically possible.

Venus also possesses atmospheric layers with significant vertical mixing. Particles and droplets constantly rise and fall, transporting materials and energy. Microbial life could exploit these dynamics to circulate through hospitable zones while avoiding deadly extremes below and above.

If such life exists, its presence might influence the atmosphere’s chemistry in measurable ways—altering the ratios of certain gases, absorbing ultraviolet light, or producing byproducts like phosphine. Detecting such anomalies is precisely what future missions aim to accomplish.

Searching for Signs of Life

The renewed interest in Venus has inspired a new generation of missions designed to probe its atmosphere and surface in detail. NASA’s upcoming DAVINCI+ mission will plunge a probe through the atmosphere, measuring its chemical composition with unprecedented precision. Meanwhile, VERITAS will map the planet’s surface in high resolution to study its geology and volcanic activity.

The European Space Agency’s EnVision mission will follow, exploring how Venus’ atmosphere interacts with its crust. Russia and India are planning complementary missions, and private initiatives are even considering sending small balloons to sample the clouds directly.

Perhaps the most promising concept involves aerial platforms—floating laboratories that could drift for weeks or months within the habitable zone. These vehicles could collect atmospheric samples, analyze droplets, and search for organic compounds, isotopic ratios, or microbial cells. The technology needed for such missions already exists, tested in Earth’s stratosphere and Mars probes.

If life is found in Venus’ clouds—alive or fossilized—it would be one of the most transformative discoveries in history. It would prove that life is not unique to Earth, that biology can emerge and endure under radically different conditions, and that the universe is teeming with possibilities.

Venus as a Warning and a Mirror

Beyond its scientific intrigue, Venus offers a sobering lesson about planetary climate. Once potentially temperate, it was undone by a runaway greenhouse effect. As carbon dioxide accumulated, the planet’s temperature rose inexorably until oceans boiled and equilibrium was lost.

This fate serves as a warning for Earth. Though our world remains far cooler, the physics of greenhouse gases is universal. Venus shows what happens when that balance tips irreversibly. It is a cautionary tale of climate gone awry—a reminder that planetary habitability is fragile and easily destroyed.

Yet Venus is also a mirror of resilience. Despite its transformation, it still holds clues to its past, and perhaps, remnants of its ancient life. In its toxic skies, in the chemical whisper of phosphine or the shimmer of ultraviolet clouds, we glimpse the persistence of nature’s creative force.

The Philosophy of Possibility

The question of life on Venus touches something deeper than science alone. It invites reflection on what it means to be alive in a universe of extremes. If even Venus—our cosmic inferno—might harbor life, then life is not fragile but fierce, not rare but inevitable.

The possibility challenges our anthropocentric assumptions. Life need not resemble us or our biochemistry. It may not breathe oxygen or depend on water. It might exist as droplets, crystals, or chemical networks that pulse with energy in ways we have yet to imagine.

Venus reminds us that life is not a narrow phenomenon bound to Earth’s conditions—it is a universal impulse, an expression of matter’s longing to organize, persist, and evolve. Whether or not we find microbes drifting in Venus’ clouds, the search itself expands our understanding of what life can be.

The Future of Discovery

Over the coming decades, Venus will once again become a focal point of exploration. New telescopes, both on Earth and in space, will continue to study its spectrum for chemical signatures. Robotic probes will descend through its skies, tasting its clouds and scanning for molecular hints of biology.

Each mission will bring us closer to answering a question as old as wonder itself: Are we alone?

If life exists on Venus—however small, however fleeting—it will reveal that the universe is far more hospitable than we once believed. It will mean that wherever conditions allow even a whisper of stability, life will find a foothold. And it will mean that Earth, far from being exceptional, is part of a continuum of living worlds.

A World Reimagined

For centuries, Venus has been both muse and mystery—the brightest light in the night, the mirror of Earth’s potential, the embodiment of both beauty and destruction. Today, it stands at the crossroads of science and imagination once more.

Whether its clouds harbor living organisms or only chemical curiosities, Venus teaches us the same enduring truth: life and death, creation and decay, are part of a single cosmic rhythm. The same processes that forged our oceans and skies also shaped this world of fire.

To gaze upon Venus is to see not just another planet, but a reflection of possibility itself—a world that once may have been alive, and may yet whisper traces of that life in its golden clouds.

The Eternal Question

Could life survive in Venus’ atmosphere? The answer, for now, remains suspended like a droplet in those alien clouds—delicate, uncertain, glimmering with promise.

But whether the answer is yes or no, the search transforms us. It reminds us that the universe is not static but alive with potential. Every planet, every cloud, every molecule might hold a secret, waiting to be unveiled by curiosity and courage.

Venus, our brilliant and perilous sister, challenges us to look beyond comfort—to seek life not where it is easy, but where it seems impossible. For it is there, in the crucible of extremes, that the essence of life may reveal itself most profoundly: resilient, adaptive, and eternal.