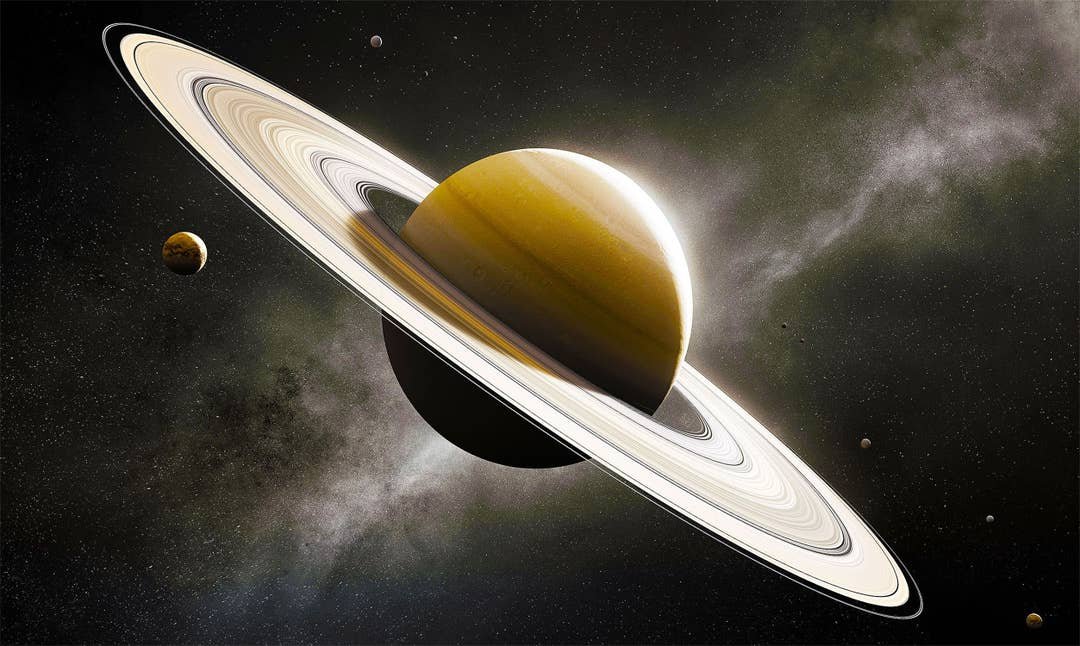

There are few sights in the universe as breathtaking as Saturn—its golden globe encircled by a halo of shimmering light. For centuries, those rings have captured the imagination of humanity. When Galileo first turned his primitive telescope toward the planet in 1610, he saw something he couldn’t comprehend. “Saturn has ears,” he wrote, unable to resolve the delicate arcs that circled the planet. It wasn’t until Christiaan Huygens observed it decades later that the truth was revealed: Saturn was surrounded by a flat, thin ring system, an otherworldly crown unlike anything else in the heavens.

But the beauty that adorns Saturn is not eternal. The same delicate rings that make it the jewel of the Solar System are also ephemeral—cosmic frost that will one day vanish. They are both ancient and young, fragile and immense, and their story is one of birth, transformation, and inevitable decay. To understand how Saturn’s rings were born and how they will die is to witness the full cycle of celestial life—creation, brilliance, and dissolution written in ice and dust.

The First Glimpse of an Enigma

For early astronomers, Saturn was already a wonder. Its slow journey across the night sky and its pale yellow glow set it apart. But when telescopes revealed the existence of its rings, humanity’s understanding of the cosmos shifted. No other planet seemed to wear such a celestial ornament.

Over the centuries, as instruments improved, we learned that the rings are vast—stretching over 280,000 kilometers from one edge to the other—yet astonishingly thin, in some places less than ten meters thick. They are composed almost entirely of water ice, with traces of rock and dust. Sunlight reflected off billions of frozen fragments gives them their ghostly brilliance.

Yet, despite their splendor, Saturn’s rings are puzzlingly young compared to the planet itself. Saturn is about 4.5 billion years old, born in the early days of the Solar System. But the rings, based on recent evidence from NASA’s Cassini mission, may be less than 200 million years old—formed long after the dinosaurs roamed Earth.

That realization changes everything. It means we are witnessing something fleeting in cosmic time—a phenomenon that might not have existed in the age of the dinosaurs and may vanish long before Earth’s distant descendants gaze up from future worlds.

The Architecture of Wonder

To the naked eye—or even through small telescopes—the rings appear as a single structure. But up close, they reveal themselves to be a system of countless individual bands, gaps, and divisions. Astronomers have named them alphabetically in the order of their discovery: D, C, B, A, F, G, and E rings.

The B Ring is the brightest and most massive, while the A Ring, divided from it by the dark Cassini Division, is adorned with wave-like ripples and spokes of charged dust. The faint C and D rings lie closer to Saturn, while the delicate F Ring—shepherded by tiny moons called Prometheus and Pandora—twists and coils like a cosmic braid. Beyond these lies the G Ring and the vast E Ring, fed by icy geysers from the moon Enceladus.

Each ring is composed of billions of particles ranging in size from microscopic grains to boulders as large as houses. They collide, clump, and shatter endlessly, creating a dynamic system that behaves like both a solid and a fluid. Gravity from Saturn and its moons sculpts these particles into patterns of astonishing complexity—spiral waves, ripples, and gaps that move like music frozen in time.

Seen from space, the rings are dazzling. Seen in physics, they are a masterpiece of orbital mechanics—a living dance choreographed by gravity and time.

The Birth of a Ringed World

The question of how Saturn’s rings were born has haunted astronomers for centuries. Were they formed with the planet itself, relics from the birth of the Solar System? Or did they appear later, carved from the debris of a shattered moon or comet?

For a long time, scientists assumed the rings were primordial—leftover material that never coalesced into a moon. This idea fit with the early view of the Solar System as a place where chaos gradually gave way to order. Saturn’s rings, in that vision, were simply remnants of creation—a fossilized disk of ice and dust.

But Cassini changed everything.

When NASA’s Cassini spacecraft arrived at Saturn in 2004, it began a 13-year exploration that transformed our understanding of the planet and its rings. Using precise measurements of gravity and particle composition, Cassini revealed that the rings contain far less mass than previously thought—too little to have survived since the planet’s formation.

Moreover, they are startlingly pure. If the rings were billions of years old, they should be darkened by cosmic dust. Instead, they remain bright and clean, composed of nearly pure water ice. This purity suggests youth. Something dramatic must have happened recently—on cosmic timescales—to give birth to this brilliant structure.

The Death of a Moon

The leading theory now is that Saturn’s rings were born from destruction. Somewhere between 100 million and 200 million years ago, a moon—perhaps one the size of Mimas or Enceladus—wandered too close to Saturn.

As it neared the planet, the immense gravitational forces began to tear it apart. The closer the moon came, the stronger the difference in gravity between its near and far sides—a force known as tidal stress. Once the moon crossed the Roche limit, the point beyond which Saturn’s tidal forces exceeded its own gravity, it was doomed.

The moon fractured, scattering fragments into orbit. Its rocky core may have plunged into the planet, while its icy mantle shattered into countless pieces that spread out into a thin, flat disk. Over time, collisions and Saturn’s magnetic field sculpted the debris into the rings we see today.

In this view, the rings are not remnants of creation—but of catastrophe. They are the graveyard of a lost moon, its icy remains still orbiting the planet that destroyed it.

The Whisper of Ancient Ice

Each particle in Saturn’s rings tells a story. They are made mostly of water ice—pure, cold, and ancient. But they are not identical. Some contain traces of rock, ammonia, or organic compounds, hints of the diverse composition of the moon that gave birth to them.

The particles reflect sunlight so efficiently that they sparkle like powdered diamonds. Yet their brilliance hides constant motion. They collide millions of times every second, breaking apart and merging again. These collisions create the fine texture seen in spacecraft images—the ripple-like structure that gives the rings their silky appearance.

Micrometeoroids continually strike the rings, darkening and eroding them. Each impact adds a whisper of cosmic dust, a reminder that the rings are slowly aging. Over time, these small interactions alter their composition, grinding the ice finer and contaminating it with darker material.

Though they seem eternal, the rings are slowly fading. Every collision, every grain of dust, every whisper of sunlight reshaping the ice is part of a long, slow erosion—the beginning of their end.

The Shepherds of Order

Saturn’s moons play a crucial role in shaping the rings. Dozens of tiny satellites orbit within or near the ring system, exerting gravitational tugs that maintain structure and prevent chaos. These moons are called “shepherds,” and their influence is both delicate and profound.

Take the F Ring, for instance—a narrow, twisted band that constantly changes shape. The tiny moons Prometheus and Pandora orbit on either side, their gravitational pulls creating waves and knots in the ring’s structure. Each time they pass, they draw out tendrils of ice that curl like cosmic ribbons.

Larger moons, like Mimas, create gaps and divisions through orbital resonance. The Cassini Division, the broad dark space between the A and B Rings, is caused by Mimas’s gravitational rhythm. Each time a ring particle orbits Saturn twice, Mimas completes one orbit, pulling the particles out of sync and clearing a gap.

These interactions are a celestial symphony of balance and disruption. The moons shape the rings, and the rings in turn influence the moons. Together they form a gravitational ballet that keeps the system alive.

Cassini’s Grand Finale and the Secrets Revealed

In 2017, after more than a decade orbiting Saturn, Cassini made its final series of daring dives between the planet and its innermost ring. This “Grand Finale” was both an ending and a revelation.

As the spacecraft plunged through the gap, it sampled the particles and gas streaming from the rings into Saturn’s atmosphere. What it found astonished scientists: the rings are actively raining onto the planet.

Tiny ice particles, pulled by Saturn’s magnetic field, spiral down into the upper atmosphere at astonishing rates—hundreds of kilograms per second. This process, called “ring rain,” means that the rings are disappearing far faster than once thought.

At this rate, Saturn’s majestic rings could be gone within 100 to 300 million years—a blink in geological time. The very phenomenon that makes Saturn so magnificent is also transient, destined to vanish. The planet will one day lose its luminous crown, leaving behind only faint traces of dust and memory.

The Silent Fall: The Rings Are Dying

The death of Saturn’s rings will be slow but inevitable. The process has already begun. As meteoroids strike the rings, they knock particles into higher orbits, where Saturn’s gravity and magnetic field drag them downward. Solar radiation and plasma interactions also create electric charges that accelerate the fall.

As the icy particles descend into Saturn’s atmosphere, they vaporize, adding water and oxygen to the planet’s upper layers. Over millions of years, this “ring rain” will strip away the material, thinning the rings until they fade entirely.

It is a haunting image—a silent snowfall of ice descending into the clouds of Saturn, disappearing forever. The rings that once defined the planet will dissolve into the very air that surrounds it.

This cosmic erosion is a reminder that nothing, not even beauty, is eternal. The same forces that create wonders also destroy them. Saturn’s rings, for all their grandeur, are temporary—a transient jewel in the vast history of the Solar System.

Echoes from the Past

If Saturn’s rings are temporary, then we may be living in a fortunate moment—the brief epoch when the planet wears its crown. It is possible that other gas giants once had similar rings, now long gone. Jupiter’s faint ring system, made of dust from its moons, may be the fading echo of such grandeur. Uranus and Neptune also have thin, dark rings—perhaps remnants of similar cataclysms.

Saturn’s rings may thus represent a phase in planetary evolution—a fleeting balance between destruction and dispersal. We are lucky to exist at a time when we can witness this splendor, to see the universe not as a static creation but as a living, changing work of art.

In another 100 million years, Saturn may look entirely different. Its rings will fade into diffuse clouds of dust. Its moons may shift orbits as the gravitational balance changes. Future observers—if any exist—may know Saturn only as a pale, golden sphere, stripped of its radiance.

The Poetry of Fragility

There is a strange poetry in the idea that Saturn’s beauty is temporary. The rings, vast as they are, are fragile—held together by delicate balances of gravity, motion, and ice. Their brilliance is born of impermanence.

In that sense, Saturn’s rings mirror the fleeting nature of life itself. They remind us that beauty does not need to last forever to be meaningful. Their grandeur is not diminished by their mortality—it is deepened by it.

Astronomers often speak of the rings in terms of mechanics and chemistry: densities, particle sizes, and orbital resonances. But there is something profoundly human in their story. They teach us that the universe’s most magnificent creations can arise from destruction, and that even the most enduring giants—planets and stars—carry within them the seeds of decay.

The rings are a cosmic elegy, a reminder that change is the universe’s only constant.

Lessons from a Dying Crown

Saturn’s rings hold clues not just about the planet’s history, but about the Solar System’s evolution. They teach us how gravity sculpts worlds, how moons form and die, and how dynamic systems can balance order and chaos for millions of years.

They also offer a warning. The same forces that give rise to beauty can, over time, erase it. Cosmic dust and time spare nothing—not even Saturn’s crown. The planet we see now is only one version of itself, one fleeting chapter in a story billions of years long.

And yet, in their dying, the rings continue to shape Saturn’s future. The water and particles raining into its atmosphere may alter its chemistry, changing how it glows in the infrared. In a way, the rings are feeding Saturn—returning to their parent planet in a final act of unity.

The Future Beyond the Rings

When the last of Saturn’s rings has fallen, the planet will still endure. Its moons—Titan, Enceladus, Rhea, and others—will continue to orbit, each with its own mysteries. Titan will still host methane lakes beneath its orange haze. Enceladus will still spew icy plumes into space, creating faint halos of new material.

Perhaps, in some distant future, collisions among these moons will birth new rings, starting the cycle again. The universe is not static—it is a story of endless renewal.

Saturn’s loss will not be a tragedy, but a transformation. The disappearance of its rings will mark the end of one chapter and the beginning of another in the planet’s long life.

A Universe of Impermanence

From afar, Saturn’s rings seem serene and unchanging, but up close they are alive with motion, creation, and decay. They are both the product of violence and the source of beauty—a contradiction that lies at the heart of the universe itself.

Every particle that shines in those rings is a remnant of something that once was—a moon shattered, a comet captured, a fragment reborn. And every one of those particles will one day fall, returning to the planet that gave it life.

The story of Saturn’s rings is the story of everything: formation from chaos, the rise of structure and beauty, the slow erosion of time, and the quiet return to nothingness. It is the story of stars, planets, and even life itself.

The Final Light

Imagine standing on one of Saturn’s moons—perhaps Enceladus or Titan—far in the future. The rings that once cast shimmering shadows across the planet’s clouds are gone. The sky is darker now, the horizon emptier. Yet in memory, they linger—a whisper of brilliance, an echo of what once circled in silence.

Perhaps civilizations long after ours will look upon Saturn and know that it once wore a crown of ice and light. They will study the records, the ancient photographs from Cassini, and marvel at what once was.

And maybe they will understand, as we do now, that beauty is not diminished by its impermanence. That to exist for a time, to shine, to fall, and to fade—that is enough.

Epilogue: The Eternal Cycle

Saturn’s rings were born from destruction, and they will die in dissolution. Between those two moments, they have gifted the universe an era of unparalleled beauty.

Their story is a cosmic poem—an ode to impermanence, to the fragile harmony between creation and decay. When we gaze upon them through telescopes or spacecraft images, we are not just seeing frozen particles orbiting a gas giant. We are witnessing the unfolding of cosmic time itself.

In their brightness, we see the power of renewal. In their fading, we glimpse the truth of all things—that nothing lasts forever, but everything leaves its mark.

And long after the rings are gone, Saturn will still turn beneath the stars, carrying within it the memory of its lost crown—a silent reminder that even in endings, there is beauty, and even in decay, there is light.