Long before ink met parchment, before alphabets were born, and even before civilizations took root, human beings were storytellers. Around fire pits and under starry skies, our ancestors spun tales to explain the mysteries of existence. Why do rivers rage? Why does fire consume? What happens after death? These were not idle questions. They were burning needs. The answers—myths—became the earliest form of philosophy, science, psychology, and art.

Across continents and centuries, certain motifs echo again and again, like recurring chords in a great symphony of human thought. Among the most enduring are the stories of floods, fires, and rebirth. These themes appear across cultures with uncanny similarity, as if humanity, no matter where or when, dreamed with a shared subconscious. But why do these motifs appear so frequently? What do they mean? And what do they reveal about us?

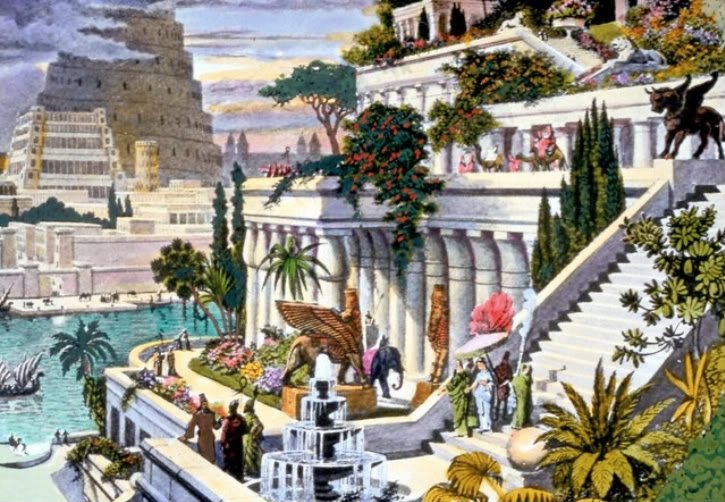

This article explores those universal themes, peeling back layers of symbolism and meaning. We will voyage through Mesopotamia and Mesoamerica, across the African savannah and the icy tundras of the North, to uncover how these three elemental forces—water, fire, and the promise of rebirth—have shaped the human imagination.

The Deluge: Flood Myths as Cosmic Cleansing

Of all mythological motifs, the great flood is perhaps the most widespread. Nearly every ancient civilization has a story of a world drowned beneath water, often as a divine punishment or a necessary cleansing.

The symbolic weight of flood myths is immense. Water is life, but it is also chaos. When rivers overflow or seas rise, they wash away the old world—its corruption, its sins, its failures. In their wake, they leave the possibility of something new.

Flood myths often reflect collective trauma—memories of tsunamis, hurricanes, or rising tides. But they also function as moral tales, warning against hubris, wickedness, or disobedience to divine laws.

The Archetype: Punishment and Renewal

In the typical flood myth, humanity has strayed. The gods are angry or disappointed. As punishment—or sometimes out of necessity—they send rain or break the dams of heaven. The waters rise, consuming cities, forests, and fields. But always, someone survives: a righteous man, a clever woman, a chosen pair. They build an ark, climb a mountain, or float upon debris. When the waters recede, the survivors rebuild, and a new age begins.

This cycle—sin, destruction, survival, rebirth—is not just religious. It reflects deep psychological truths. It echoes the stages of transformation we all endure: the collapse of our old selves and the painful birth of the new.

Mesopotamia: Gilgamesh and Utnapishtim

Among the oldest flood myths comes from ancient Mesopotamia, where Utnapishtim tells Gilgamesh how the gods, weary of human noise and chaos, unleashed a flood to destroy the world. Utnapishtim alone is warned and builds a massive boat, preserving his family and animals. When the flood ends, he releases birds to find land—an image mirrored later in biblical accounts.

The striking parallels between this and the Noah story suggest a shared cultural memory, perhaps based on real flooding in the Tigris-Euphrates region. But more than that, they speak to the human yearning for second chances.

India and Manu

In Indian mythology, Manu, the first man, saves a small fish who later reveals himself as the god Vishnu. The fish warns of an impending deluge, and Manu builds a boat that rides out the flood. In some versions, the boat is anchored to a mountain peak. The symbolism is rich: a divine warning, a test of faith, and a rebirth into a purer world.

The Americas and Beyond

In Mesoamerican myths, the gods often destroy the world through floods, followed by a new creation. In Aztec belief, we live in the fifth world—four others were destroyed, one by flood. In Native North American tales, water often covers the world until animals or gods create land anew from mud or seeds.

Across Africa, Polynesia, and Southeast Asia, flood stories persist. Sometimes the cause is divine anger; other times, it’s a mistake or the greed of humans. Yet always, the message remains: the world can be washed clean, and with it, the soul.

The Sacred Flame: Fire as Destruction and Illumination

Where water cleanses, fire transforms. It is the second great force in mythology—both feared and worshipped. Fire devours, but it also gives light. It cooks food, warms homes, drives away predators. Yet when unleashed, it destroys forests, razes cities, and sears the skin.

In myths, fire often represents knowledge, power, and divine wrath. It is stolen from the gods, used as a weapon, or sent as punishment. But it also becomes the spark of civilization, the first step from beast to human.

The Fire Bringer: Prometheus

In Greek mythology, the titan Prometheus defies Zeus by stealing fire and giving it to humanity. For this, he is punished—chained to a rock where an eagle eats his liver daily. Yet Prometheus is also seen as a hero, a rebel, a symbol of human striving. Fire in this myth is enlightenment, technology, the origin of progress.

But the fire is stolen. It is not ours by right. This suggests an ambivalence—power comes at a cost. Every civilization must wrestle with the dangers of its own tools.

Hindu Agni and the Fire Ritual

In Hinduism, fire is divine. Agni, the fire god, is a messenger between humans and gods. Through yajnas (fire rituals), offerings are transformed by flame and sent to the heavens. Fire is the link between the physical and spiritual worlds, a holy portal.

Here, fire is not feared, but revered. It purifies. It carries prayers. It is both presence and path.

Fires of Judgment

In many traditions, fire is the instrument of divine justice. In the Bible, God rains fire and brimstone on Sodom and Gomorrah. In Zoroastrianism, the end of the world comes with a river of molten metal that will purge the wicked.

In Norse mythology, the fire giant Surtr leads the forces of chaos in Ragnarök, wielding a flaming sword to burn the world. Yet even in this apocalypse, fire is not the end. From the ashes, a green world is reborn.

Fire myths are often ambivalent. They warn of unchecked ambition, divine anger, or cosmic reset. But they also celebrate discovery, illumination, and the alchemy of transformation.

The Phoenix Principle: Rebirth and Renewal

If flood myths wash the world clean and fire myths burn it down, rebirth myths rebuild. These are the stories of resurrection, reincarnation, renewal—the idea that death is not the end, but a passage to something new.

Rebirth myths are deeply tied to nature’s cycles. The sun sets, but rises again. The seasons change, but return. Seeds fall, rot, and sprout anew. The idea of rebirth provides hope, a narrative arc for existence, and a way to cope with mortality.

The Dying and Rising God

Many mythologies contain a figure—often a god—who dies and returns. In Egyptian myth, Osiris is killed and dismembered, but resurrected by Isis. He becomes lord of the underworld, symbolizing life after death.

In Greek mythology, Persephone is taken to the underworld, causing winter. Her return each spring brings renewal. Dionysus, too, is torn apart and reborn, embodying ecstasy and the cycle of the vine.

Christianity centers on the resurrection of Jesus, whose death and rising promise eternal life to believers. His story echoes older myths, yet also transforms them. Rebirth becomes not just a natural cycle, but a divine gift.

Eastern Reincarnation

In Hinduism and Buddhism, rebirth is not metaphor but metaphysical law. The soul, or atman, passes through many lives, shaped by karma. The goal is not just to be reborn, but to transcend rebirth entirely—to reach moksha or nirvana, freedom from the cycle.

This concept reframes life and death. They are not opposites, but steps on a path. Every ending is a new beginning.

Shamanic Death and Transformation

In many indigenous cultures, rebirth is not only cosmological—it is psychological. Shamans undergo symbolic death through isolation, illness, or vision quests, returning transformed. These personal rebirths mirror the cosmic ones.

This reflects a powerful truth: we all experience symbolic deaths—failures, heartbreaks, losses. Myths of rebirth give us a map for surviving them. They remind us that after the fall comes the rise.

The Trinity of Transformation

Floods, fires, and rebirth are not isolated motifs. They are linked, forming a trinity of transformation. First comes destruction—by water or fire. Then, in the ashes or silence, something new is born.

This structure appears in countless stories:

- In flood myths, the world is cleansed and reborn.

- In fire myths, the old is burned away to make room for the new.

- In rebirth myths, death becomes a doorway.

Why does this pattern resonate so deeply? Perhaps because it mirrors our own lives. We suffer, we break, we lose. But we also heal, change, and begin again. Myths give us permission to hope. They remind us that destruction is not the end, but part of the journey.

Why These Themes Endure

Floods, fires, and rebirth have never lost their relevance. In modern times, we see them in post-apocalyptic fiction, in superhero origin stories, in climate change fears, and in spiritual awakenings.

The great flood becomes a metaphor for environmental catastrophe. The cleansing fire becomes the power of revolution. Rebirth appears in therapy, in addiction recovery, in the decision to start over.

These themes speak to something primal. They are not just about gods or magic—they are about us. About how we endure. About how we begin again.

Conclusion: The Mythic Pulse of Humanity

We live in a technological age, but the ancient myths still breathe beneath our modern lives. We still fear floods, literal and metaphorical. We still burn with ambition and suffer the consequences. We still long for rebirth when life becomes too heavy.

The myths of floods, fires, and rebirth are not relics. They are reflections. They mirror our struggles, our resilience, and our eternal dance with transformation. In every culture, across every era, we have told these stories—not just to remember, but to survive.

And as long as we tell them, we are never truly lost. Because in myth, there is always a second chance. Always a spark in the ashes. Always a dawn after the deluge.