In the ancient land of Egypt, where the golden desert met the life-giving waters of the Nile, time was not measured by clocks or calendars, but by the steady rhythm of nature. The sun’s daily journey across the sky was both a divine act and a practical guide, marking the beginning and end of human labor, worship, and rest. Every sunrise was the rebirth of Ra, the sun god, and every sunset his descent into the underworld. To live in ancient Egypt was to move in harmony with this eternal cycle—to wake, work, eat, and pray beneath the gaze of gods whose presence illuminated every moment of the day.

The 24-hour routine of an ancient Egyptian was more than a schedule; it was a spiritual dance with time itself. Life along the Nile was cyclical, reflecting the patterns of the natural world: the flooding of the river, the planting of seeds, the harvest of grain, and the journey of the soul. Yet within this grand cosmic order, daily life unfolded with remarkable familiarity—families rising at dawn, artisans laboring in the heat, children learning to read hieroglyphs, and priests greeting the morning with hymns.

This is the story of a day in ancient Egypt—a day that begins with the first glint of sunlight on the eastern horizon and ends with the quiet of night beneath a canopy of stars. Through the eyes of farmers, scribes, artisans, and priests, we glimpse the rhythm of life that pulsed through this ancient civilization, one sunrise and one sunset at a time.

Dawn: The Awakening of Ra

As the eastern sky blushed with the first light of dawn, ancient Egyptians rose with reverence and purpose. For them, the sunrise was not merely a natural event—it was a divine rebirth. The sun god Ra had triumphed once again over darkness, sailing his golden barque through the underworld to rise renewed in the morning sky. His emergence heralded the renewal of life, light, and order.

The homes of ancient Egyptians, constructed from sun-dried mud bricks, began to stir with quiet activity. Families slept on woven reed mats or low wooden beds, often with little more than linen sheets for comfort. With the first light, household fires were rekindled. The air filled with the scent of baking bread as women ground emmer wheat and barley on stone querns, preparing dough for flat loaves cooked on clay ovens.

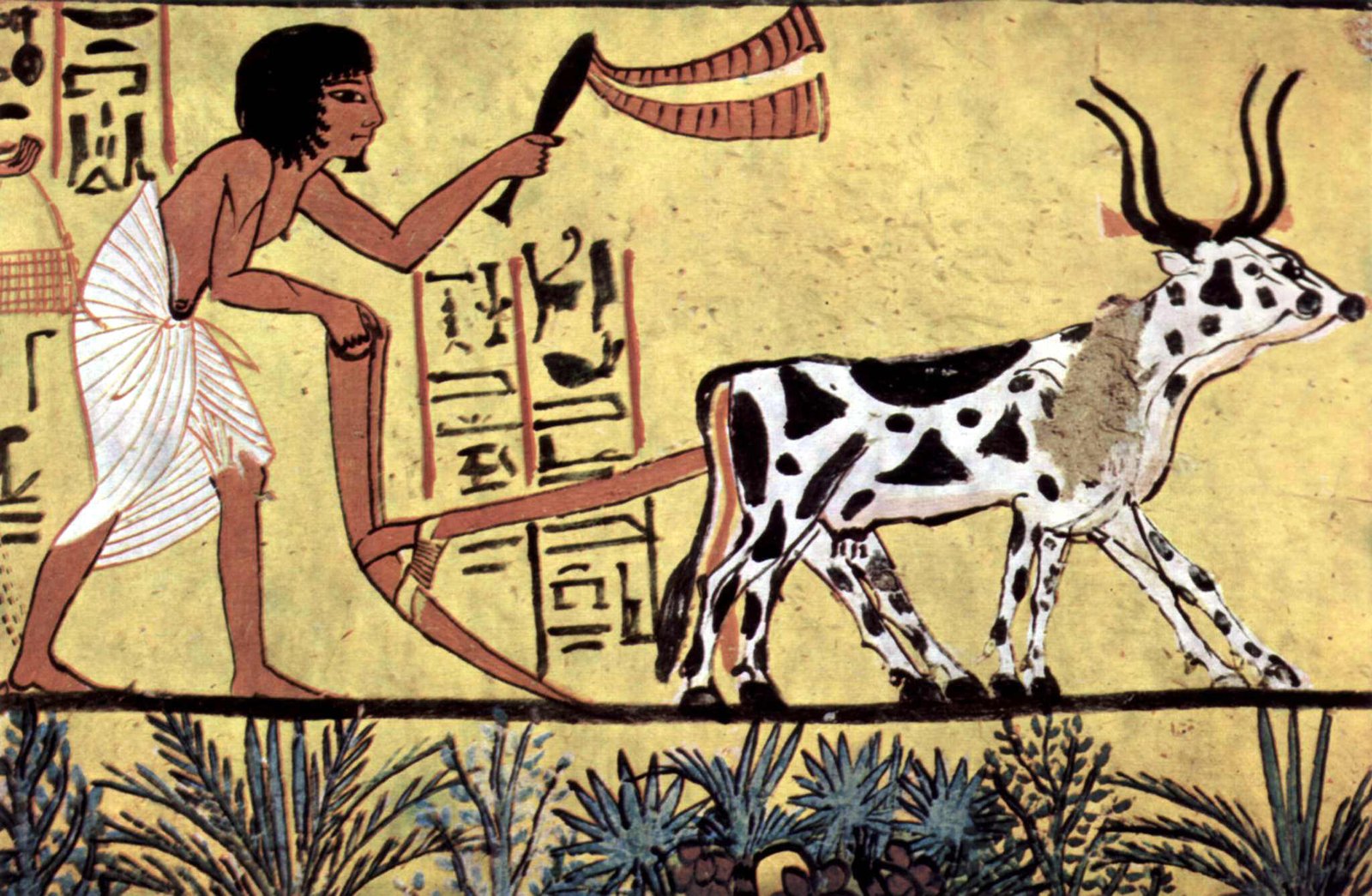

Outside, the Nile gleamed like liquid gold, reflecting the awakening world. Farmers, dressed in simple linen kilts, gathered their tools—hoes, sickles, and baskets woven from palm fibers. They stepped into the fertile fields left behind by the receding floodwaters, where black silt awaited their touch. The day’s work began as the horizon brightened and the call of ibises echoed across the riverbanks.

In temples across the land, priests performed the Opening of the Shrine ceremony. They purified themselves in sacred pools, donned linen garments, and approached the inner sanctum where the statue of the deity rested. With incense smoke curling in the air, they opened the shrine doors to greet the god with hymns and offerings. For the Egyptians, dawn was a sacred act of cosmic renewal—both the sun and the gods required human devotion to sustain the balance of ma’at, the divine order of the universe.

Morning: The Pulse of Daily Life

By mid-morning, Egypt was alive with movement. The villages and cities bustled with artisans, merchants, farmers, and officials each attending to their duties. Labor was both an obligation and a form of worship—every action, from plowing a field to carving a statue, was seen as a contribution to ma’at, the harmony that kept chaos at bay.

For the common farmer, the morning was devoted to the land. The fertile floodplain, renewed annually by the Nile’s inundation, demanded constant attention. Men and women worked side by side, guiding oxen that pulled wooden plows through the rich soil. In irrigation canals, others controlled the flow of water using shadoofs—long poles with counterweights that lifted water from the river into ditches. This rhythmic motion, perfected over generations, sustained the crops that fed an empire.

The diet of the Egyptians reflected the gifts of their river. Bread and beer were staples, often accompanied by onions, dates, figs, and fish. Beer, brewed from barley, was more nutritious than intoxicating—a liquid bread consumed by adults and children alike. The mid-morning meal was simple yet satisfying, eaten under the shade of palm trees or on the steps of mud-brick homes.

In workshops scattered throughout towns like Thebes and Memphis, artisans began their tasks with precision. Stone carvers chiseled limestone for temples, while goldsmiths hammered jewelry destined for nobles and pharaohs. Potters shaped clay vessels on spinning wheels, their hands wet with the same Nile mud that sustained life. Scribes, seated cross-legged on the floor, dipped reed brushes into black ink and recorded everything from grain inventories to royal decrees on papyrus scrolls.

For the elite, mornings might unfold differently. Nobles and officials, living in larger homes with painted walls and lush gardens, oversaw agricultural estates and administrative matters. Their days were filled with meetings, correspondence, and offerings to local temples. Women of the household, often educated and influential, managed servants, children, and domestic affairs. They adorned themselves with fine linen and kohl-lined eyes, embodying ideals of beauty that mirrored divine grace.

Children, regardless of status, were considered blessings from the gods. Boys often learned their father’s trade, while daughters helped in household tasks. The children of scribes and officials might attend temple schools, where they memorized hieroglyphs, practiced mathematics, and learned the hymns and wisdom texts that preserved Egyptian culture. Education was not simply about learning to read—it was a sacred duty to preserve maat through knowledge and discipline.

Midday: The Heart of the Sun

As the Sun reached its zenith, the air shimmered with heat. In the desert lands of Egypt, midday was both the most powerful and the most perilous time of day. The blazing disk of Ra dominated the sky, his strength at its peak. People paused in their labor, seeking shade beneath palm fronds or the cool interiors of mud-brick houses.

In religious symbolism, this was the hour when Ra sailed triumphantly across the sky in his solar barque, accompanied by other gods. But it was also a time of vigilance, for the Sun’s power could easily burn as it could bless. In some regions, priests performed midday offerings, presenting food, incense, and hymns to ensure Ra’s continued strength.

For ordinary Egyptians, midday brought rest and nourishment. Farmers ate simple meals—flatbread dipped in oil or lentil stew, dried fish, or figs. The wealthy dined more lavishly, with roasted duck, vegetables, and fruit, often accompanied by music and wine. The sound of flutes, harps, and sistrums might drift from open courtyards where families gathered to escape the heat.

The Nile itself became a place of refreshment. Men bathed in its waters, women washed clothing along its banks, and children splashed and played in the shallows. The river was more than a source of life; it was a sacred artery flowing from the gods themselves. To the Egyptians, its annual flooding was not a random event but the tears of the goddess Isis mourning her husband Osiris, whose resurrection symbolized the fertility of the land.

In cities like Thebes and Memphis, midday might also bring processions. Priests carried statues of gods through temple courtyards, shaded by canopies and accompanied by chanting devotees. The scent of myrrh and frankincense filled the air, and petals scattered across the ground marked the path of the divine. These rituals reaffirmed the bond between the gods and the people, ensuring the continued favor of the heavens upon the kingdom.

Afternoon: The Labor of Creation

As the Sun began its descent, the tempo of daily life quickened once again. The late afternoon was a time of renewed productivity—a final effort before the coming of night. Farmers completed their tasks, guiding livestock back toward pens and gathering the day’s harvest. Fields of flax and barley rippled in the fading light, the air filled with the hum of insects and the calls of herons.

Artisans in workshops focused on finishing touches. Sculptors smoothed stone statues, adding fine details to faces meant to last for eternity. Painters applied pigments of red ochre, blue copper oxide, and yellow ochre to tomb walls depicting scenes of daily life and divine judgment. Every stroke of the brush was more than decoration—it was a ritual act of immortality. Egyptians believed that to depict something was to give it life, so every image of food, every painted servant, every boat or tool in a tomb ensured its presence in the afterlife.

In temple precincts, the afternoon was marked by the Offering of the Second Hour. Priests once again approached the gods with incense and prayers, maintaining the divine cycle that mirrored the Sun’s path. The gods, like humans, were sustained by daily ritual; neglect could bring imbalance to the cosmos.

Children, having completed their studies or chores, often played outside as the shadows lengthened. Games such as senet—a board game symbolizing the passage of the soul through the afterlife—were common, as were wrestling and mock hunts. Their laughter mingled with the lowing of cattle and the rustling of date palms in the warm breeze.

For the scribes and officials, the afternoon brought closure to administrative duties. Records were checked, reports completed, and letters sealed with clay impressions bearing royal or personal insignia. The bureaucracy of Egypt was vast, but it functioned with a precision that mirrored the order of maat. From the collection of taxes to the distribution of grain, everything was meticulously documented. Writing was both power and permanence—it ensured that no act, no life, no event would be forgotten.

Sunset: The Descent into Night

As the horizon glowed red and gold, Egyptians turned their eyes westward. Sunset was a sacred moment—a time of transition between the worlds of the living and the dead. Just as the Sun sank into the western horizon to begin its nightly journey through the underworld, so too did souls journey westward after death. The necropolises of Thebes, Saqqara, and Giza all lay on the west bank of the Nile, symbolizing this eternal passage.

At dusk, life slowed. Farmers returned home carrying baskets of produce, children trailed behind them, and the smell of evening fires filled the air. Women prepared the evening meal, often lighter than the one at midday—perhaps bread with lentils, cheese, or dates. Families gathered in courtyards to eat, share stories, and watch the colors fade from the sky.

In temples, priests performed the evening rites, offering prayers to Ra as he entered the realm of darkness. Hymns were sung to accompany his journey, and lamps were lit to guide his way. For the devout, this was also a time to honor Osiris, the god of the dead, who reigned in the underworld and promised rebirth to all who lived in accordance with maat.

The setting Sun also marked a shift in human activity. In urban centers, the streets grew quiet except for the calls of guards or the soft notes of music drifting from homes. In rural villages, families slept early to rise with the dawn. The stars emerged, forming constellations that mirrored divine stories—the falcon of Horus, the goddess Nut arched across the sky. Astronomer-priests observed these patterns carefully, for celestial order was the foundation of Egyptian calendars, rituals, and architecture.

To the ancient Egyptians, night was not merely darkness—it was mystery, regeneration, and the realm of dreams. The Sun’s journey through the underworld symbolized the eternal cycle of death and rebirth that governed all existence. As they lay down to rest, Egyptians believed they participated in this cosmic rhythm, trusting that both they and the Sun would rise again with the dawn.

Night: The Realm of Stars and Spirits

When the Sun had vanished completely, Egypt entered a world illuminated by the moon and stars. The cool night air carried the scent of the river and the distant sounds of animals—frogs croaking, dogs barking, donkeys braying in the dark. For most people, the night was a time of rest and renewal, but it was also filled with unseen forces.

Egyptian mythology taught that Ra now traveled through the twelve gates of the underworld, facing serpents, demons, and the great serpent Apep who sought to devour his light. Priests in temples recited spells to aid Ra’s victory, ensuring that dawn would return. In homes, protective amulets—such as the Eye of Horus or the scarab—guarded sleepers against malevolent spirits.

The moon, associated with the god Khonsu and the ibis-headed Thoth, ruled the night. Its phases were carefully observed, used to mark festivals, and linked to the cycles of fertility and time. During full moons, the world seemed bathed in silver, and temple walls glowed softly in the lunar light.

Night was also a time for dreams, which Egyptians regarded as messages from the gods. Dream interpreters served in temples, decoding symbols and visions that guided personal and political decisions. For the pharaoh, dreams could foretell victory or disaster, divine approval or wrath. For ordinary people, dreams connected them to ancestors and deities, a nightly reminder that the veil between worlds was thin.

As the night deepened, silence descended. Lamps flickered out one by one, and the stars wheeled slowly across the sky. The Milky Way, which Egyptians saw as a celestial river, mirrored the Nile below. This symmetry between heaven and Earth reinforced their belief that the cosmos was a single, unified body—a balance of life, death, and rebirth.

The Eternal Cycle

To an ancient Egyptian, the passage of a single day was a microcosm of eternity. Dawn was creation, noon was life at its height, sunset was death, and night was the promise of rebirth. Each 24-hour cycle mirrored the great cosmic drama of Ra’s voyage, of Osiris’s resurrection, and of humanity’s place within the divine order.

Time in ancient Egypt was not linear but cyclical. The repetition of days, seasons, and years reflected the unbroken continuity of existence. This belief shaped everything from architecture to religion. Temples were aligned with celestial events; tombs were designed as eternal homes; festivals reenacted the victories of gods over chaos.

The Egyptians measured hours by the Sun’s position and by water clocks at night, but they did not need precision to live in harmony with time. Their world was synchronized with nature’s rhythm—an unhurried, sacred tempo that wove together survival, faith, and beauty.

Even today, when one stands at dawn by the Nile and watches the first rays of sunlight break over the horizon, it is possible to imagine the same scene thousands of years ago. The same golden light, the same river, the same human longing for order and meaning. The ancient Egyptians are gone, but their rhythm endures—in the flow of the Nile, in the march of the Sun, and in the eternal bond between the heavens and the Earth.

A Civilization in Motion

From sunrise to sunset, the life of an ancient Egyptian was shaped by a profound respect for balance and continuity. Their daily routines were not mundane repetitions but sacred acts woven into the cosmic fabric. Every loaf baked, every field tilled, every prayer uttered reinforced their harmony with the universe.

To live in ancient Egypt was to inhabit a world where the divine and the ordinary were inseparable. The gods walked beside men, and time itself was a living being. The Nile rose and fell as predictably as the Sun, and in that rhythm, the Egyptians found both sustenance and meaning.

Theirs was a civilization sustained by the simple yet profound understanding that life is cyclical, not fleeting; that death is but another form of dawn. Their 24-hour routine was a reflection of eternity—a daily reenactment of creation and renewal.

As the Sun sets behind the western desert and rises once more above the eastern horizon, the eternal rhythm continues. The same light that once glowed on the temples of Karnak and the pyramids of Giza still touches the sands today, carrying forward the heartbeat of a people who lived in harmony with the cosmos.

In every sunrise, the Egyptians saw promise; in every sunset, peace. Between them stretched the fullness of life—the brief yet luminous journey from dawn to dusk that mirrored the endless voyage of the gods. And in that dance of light and shadow, they found the essence of eternity.