Long before the rise of Egypt’s pyramids or the glory of Rome, there was Sumer—the land “where writing, cities, and history began.” Nestled in the fertile cradle between the Tigris and Euphrates Rivers, in what is now southern Iraq, the Sumerian civilization emerged more than 6,000 years ago. It was here, in this lush yet demanding landscape, that humankind first learned to live not as scattered tribes but as citizens of cities—builders of temples, makers of laws, and writers of words that would echo through time.

Sumer was not just the birthplace of a civilization—it was the birthplace of civilization itself. It was in Sumer that humanity first transformed chaos into order, invented government, codified religion, and recorded its own story in the first written language. Every modern city, every law, every library, every act of writing owes a quiet debt to this ancient world of clay tablets and ziggurats.

The Land Between Two Rivers

The Sumerians lived in Mesopotamia, a Greek word meaning “the land between the rivers.” The Tigris and Euphrates flowed from the mountains of Anatolia, winding through dry plains before emptying into the Persian Gulf. Between these rivers stretched a landscape both generous and perilous—a place where fertile soil promised abundance, but unpredictable floods could destroy everything in a single season.

This delicate balance between life and loss shaped the Sumerian soul. The people of Sumer learned to harness the power of the rivers, building canals, levees, and irrigation systems that turned the barren desert into a garden of wheat, barley, and dates. This mastery of water was the first great step toward civilization. It required organization, leadership, and cooperation—foundations of government itself.

Yet Sumer’s environment also bred humility. The Sumerians knew that nature was capricious and that survival depended on both ingenuity and reverence. Their gods reflected this understanding—deities of water, sky, and earth who could bless or curse with equal power.

The Birth of the City

Before Sumer, humans lived as farmers in small villages or as nomads wandering in search of food. But around 4000 BCE, something extraordinary happened. Small settlements in southern Mesopotamia began to merge into larger, more complex communities. These were not mere clusters of homes—they were true cities.

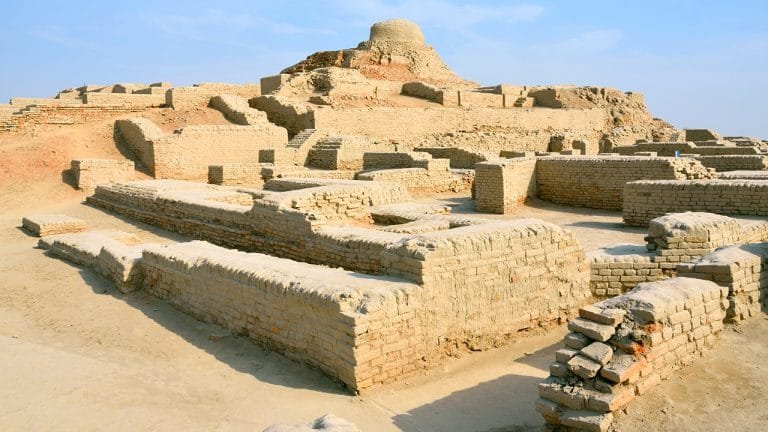

Uruk, Eridu, Lagash, Ur, Kish, and Nippur—these names still resonate through history as the first urban centers on Earth. Uruk, perhaps the greatest of them all, became a sprawling metropolis of tens of thousands of people. Within its walls rose monumental temples, administrative buildings, workshops, and homes. For the first time, humanity built not just for survival but for meaning, permanence, and pride.

In these early cities, every stone, every street, and every law was an experiment in social order. People organized themselves into classes—priests, craftsmen, farmers, and laborers—each contributing to a new kind of collective life. Trade flourished; scribes kept records of grain and livestock; artisans created objects of both beauty and utility. Out of chaos came order, and out of necessity came civilization.

The Invention of Writing

The most revolutionary invention in human history was born in Sumer around 3200 BCE—writing. What began as simple marks on clay tablets evolved into cuneiform, the world’s first written language. The word “cuneiform” comes from the Latin cuneus, meaning “wedge,” referring to the wedge-shaped impressions made by a stylus pressed into soft clay.

At first, writing served practical purposes. Sumerians used it to keep track of trade, taxes, and agricultural yields. Each symbol represented a commodity or number—a system of accounting for a society that had grown too complex to rely on memory alone. But as time passed, writing became more than bookkeeping. It became a tool for storytelling, law, and myth.

Through cuneiform, the Sumerians began to write hymns to their gods, royal decrees, and even poetry. The Epic of Gilgamesh, the world’s oldest known literary masterpiece, was composed in Sumerian and later transcribed into Akkadian. It tells the story of a legendary king who sought immortality—a tale that still speaks to humanity’s eternal struggle with mortality and meaning.

Writing gave the Sumerians the power to preserve thought beyond the life of the thinker. For the first time, human memory transcended generations. History itself began in Sumer.

The Gods of Sumer

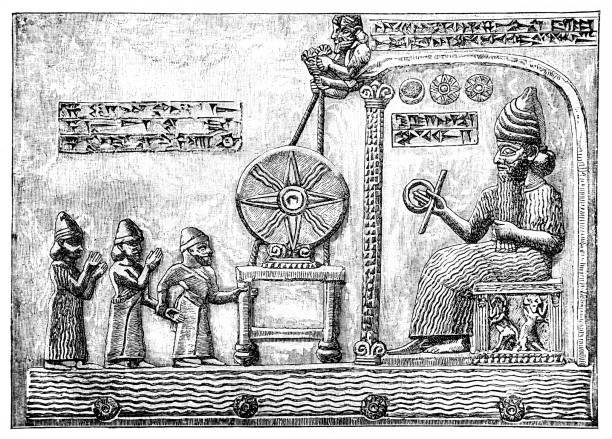

Religion was the heartbeat of Sumerian life. Every city belonged to a patron deity who was believed to own the land, the people, and even the king. The Sumerians saw their gods not as distant beings but as powerful rulers who demanded service, worship, and sacrifice.

At the center of each city stood a ziggurat—a massive, tiered temple rising like a mountain toward the heavens. These ziggurats symbolized a bridge between earth and sky, a physical link between humans and their divine overseers. The priests who tended them were among the most powerful figures in Sumerian society, controlling not only religious rituals but also the economy, education, and administration.

The Sumerian pantheon was vast and complex. Anu ruled the heavens; Enlil governed the air and wind; Enki (or Ea) presided over water, wisdom, and creation. Inanna, goddess of love and war, embodied both fertility and ferocity. Each god had its own myths, temples, and cults, and together they formed a cosmic order reflecting the rhythms of nature and society.

Sumerian religion also reflected the fragility of life in their unpredictable world. Their myths spoke of floods, droughts, and divine wrath. Humanity existed at the mercy of forces far beyond control, and the gods themselves were not always benevolent. The Sumerians worshipped with awe, fear, and devotion—seeking favor through rituals that bound heaven and earth together.

Kings and Kingdoms

As cities grew, so did their ambitions. Each Sumerian city-state was an independent kingdom, ruled by a lugal—a “big man” or king—who served as both political and religious leader. These kings claimed divine support, often presenting themselves as chosen by the gods to maintain order and justice.

Among the earliest and most famous rulers was Gilgamesh, the semi-mythical king of Uruk. Whether he was a real person or a legendary hero, his name became synonymous with the ideals of kingship—strength, wisdom, and the quest for immortality.

Over time, power struggles among city-states became common. Sumer was rarely unified; instead, it was a patchwork of rival cities vying for dominance. Yet this competition also fueled innovation. As kings sought to glorify their cities, they commissioned monumental architecture, codified laws, and fostered advances in art and science.

One of the most remarkable early rulers was Urukagina of Lagash (around 2350 BCE), who issued what may be the world’s first legal reforms—an early precursor to codified law. A few centuries later, Ur-Nammu of Ur established one of the first formal law codes, setting precedents for the later Babylonian Code of Hammurabi.

These early kings laid the foundation for governance itself—the idea that societies could be ruled by laws rather than whims, and that power carried both privilege and responsibility.

The Economy of Clay and Trade

Sumer’s wealth rested on the fertile soil of the Mesopotamian plain and the ingenuity of its farmers. Using irrigation canals, the Sumerians turned arid land into productive fields. They grew barley, wheat, and flax, and raised cattle, sheep, and goats. Surpluses of grain allowed people to specialize in other trades—craftsmen, potters, weavers, and metalworkers.

Because Sumer lacked natural resources like wood, stone, and metal, its people became avid traders. They exchanged grain, textiles, and crafts for timber from Lebanon, copper from Oman, and precious stones from Persia and Afghanistan. Trade caravans and riverboats connected Sumer with distant lands, spreading not only goods but ideas and culture.

To manage this complex economy, the Sumerians developed advanced systems of weights, measures, and accounting. Clay tablets became the ledgers of an expanding commercial world. Each transaction—every sale, debt, or exchange—was inscribed for permanence, marking the dawn of economic record-keeping.

This thriving trade network made Sumer the economic heart of the ancient Near East and set the stage for future empires that would rise in its shadow.

The Science of the Heavens and the Earth

The Sumerians were not only builders and traders—they were thinkers, observers, and scientists. Their need to manage agriculture and religious rituals led them to study the natural world with precision.

They tracked the movements of the Sun, Moon, and stars, creating one of the earliest calendars. Time itself became measurable—a revolutionary idea that allowed farmers to predict floods, priests to schedule festivals, and rulers to organize labor. They divided the circle into 360 degrees and the hour into 60 minutes, systems still in use today.

In mathematics, the Sumerians used a base-60 (sexagesimal) number system, which later influenced Babylonian astronomy and remains embedded in how we measure time and angles. In medicine, they recorded symptoms, treatments, and prayers for healing, blending empirical observation with spiritual belief.

Even in their myths, one can sense a proto-scientific curiosity—a desire to understand creation, mortality, and the structure of the cosmos. To the Sumerians, knowledge was sacred, and the pursuit of it was an act of worship.

Art, Music, and the Human Spirit

The Sumerians were also artists and dreamers. They filled their temples with statues of worshippers, eyes wide and hands clasped in perpetual devotion. They carved cylinder seals—tiny masterpieces that served as signatures, each one a swirl of gods, animals, and geometric patterns pressed into clay.

Their art reflected both realism and symbolism. Figures were stylized yet expressive, their faces revealing reverence, fear, or joy. Jewelry made of gold, lapis lazuli, and carnelian adorned both the living and the dead.

Music, too, was vital to Sumerian life. Harps, lyres, and flutes accompanied songs of worship and celebration. Archaeologists have even unearthed fragments of musical notation from ancient Mesopotamia, suggesting that Sumerians understood harmony and rhythm thousands of years before modern notation was invented.

Through their art, the Sumerians expressed the universal human desire to transcend time—to leave behind something that speaks long after the artist is gone.

Women in Sumerian Society

Though Sumer was a patriarchal society, women held notable positions and influence. They could own property, engage in trade, and serve as priestesses. Some high priestesses, such as Enheduanna—the daughter of King Sargon of Akkad—became powerful political and spiritual figures.

Enheduanna is particularly remarkable because she is the first known author in human history whose name is recorded. Her hymns to the goddess Inanna are both poetic and profound, blending devotion with insight. In her words, we hear not only the voice of a woman but the first voice of individual expression ever written.

Through figures like Enheduanna, we glimpse a society that, despite its hierarchies, recognized intellect and faith as transcending gender.

The Fall of Sumer

No civilization lasts forever. By around 2000 BCE, the Sumerian city-states began to decline. Continuous wars among cities weakened their power, while environmental challenges—such as soil salinization from irrigation—reduced agricultural productivity. The once-rich farmlands began to turn barren, and famine spread.

Into this weakened landscape marched new powers. The Akkadians, a Semitic-speaking people from northern Mesopotamia, rose under the leadership of Sargon the Great around 2334 BCE. Sargon conquered Sumer and established the world’s first empire. Though the Sumerians were absorbed into the Akkadian realm, their language, culture, and institutions endured.

Even after Sumer’s political fall, its influence never vanished. The Akkadians, Babylonians, and Assyrians all inherited Sumerian ideas—writing, religion, law, and science. The Sumerian language continued to be studied as a sacred tongue, much like Latin centuries later.

The civilization that began in the marshlands of Mesopotamia became the seed from which all later empires would grow.

The Legacy of Sumer

The legacy of the Sumerians is immeasurable. They gave humanity its first written words, its first cities, its first organized religion, and its first legal codes. They turned the unpredictable rhythms of nature into measurable time and the chaos of oral memory into permanent record.

Every modern city, from New York to Tokyo, carries the DNA of Uruk and Ur—the division of labor, centralized government, trade, and architecture. Every time we write a law, count an hour, or sign a document, we are performing acts that began in Sumer.

Their myths, too, echo through time. The flood story in The Epic of Gilgamesh parallels the biblical tale of Noah, showing how deeply Sumerian thought shaped later cultures. Even the concept of paradise—a walled garden of abundance—has its roots in ancient Mesopotamian imagery.

Sumer’s greatest gift was not its temples or cities, but its idea: that humanity could build, organize, and remember—that we could shape our destiny through knowledge and creativity.

Rediscovery and Modern Understanding

For thousands of years after its fall, Sumer was forgotten. Its cities were buried beneath sand and time, its language lost. Only in the 19th century did archaeologists begin to uncover its secrets.

When explorers dug into the mounds of Mesopotamia, they found clay tablets covered with strange wedge-shaped marks. These tablets—hundreds of thousands of them—revealed a lost world. Piece by piece, scholars deciphered cuneiform, unlocking the voices of the first writers.

Through these texts, we came to know the Sumerians again—their fears, hopes, prayers, and laws. We discovered that they were not primitive, but profoundly human: intelligent, organized, poetic, and deeply spiritual.

The rediscovery of Sumer changed our understanding of history itself. Civilization did not begin with Greece or Rome, but thousands of years earlier, in the river valleys of Mesopotamia.

The Spirit That Endures

To study Sumer is to witness the dawn of humanity’s conscious history. The Sumerians were the first to ask questions that still define us: Who are we? Where do we come from? What is the purpose of life and death? How can we live together in justice and harmony?

Their answers were written in clay, but their spirit endures in every word, city, and law that followed. They built a world where memory could outlast mortality, where thought could survive the thinker.

Standing amid the ruins of Uruk or Eridu, one can almost feel their presence—the hum of their markets, the chants of their priests, the scratch of their stylus on wet clay. The wind over the Euphrates carries their echoes, whispering of the first time humanity looked upon itself and said, “Let us make something that lasts.”

The Cradle of Us All

The story of Sumer is the story of us all. From their irrigation canals came our agriculture; from their city walls came our architecture; from their tablets came our literature. They were the first to turn imagination into civilization, the first to transform survival into meaning.

In their ziggurats, we see the ancestors of our cathedrals and skyscrapers. In their laws, we see the roots of justice. In their myths, we see our own search for immortality.

The Sumerians may have vanished, but their light never faded. Every civilization that rose after them stood on the foundation they built. To know Sumer is to trace the origin of humanity’s greatest gift—our capacity to dream, to build, and to remember.

The Eternal Echo of Sumer

Though the marshes of ancient Mesopotamia have long dried and the great ziggurats have crumbled into dust, the Sumerians still speak. Their words, pressed into clay more than five thousand years ago, continue to tell us who we are.

They remind us that history did not begin with kings or conquests, but with the quiet scratch of a stylus, the first mark of thought made permanent.

From that moment, humanity ceased to be a whisper carried by time and became a voice that endures forever.

That voice—the voice of Sumer—still calls to us through the ages. It speaks of creation, struggle, and wonder. It tells us that even the smallest mark on clay can shape eternity.

And so, beneath the sands of Iraq, where the Tigris and Euphrates still flow, the spirit of Sumer endures—the first civilization, the first storytellers, the first dreamers who dared to write the story of the world.