Long before humans walked upright across savannas or wrote stories about their origins, the Earth was alive with creatures so strange and magnificent that even today they feel unreal. Towering reptiles ruled tropical forests, fur-covered giants thundered across icy plains, and bizarre marine beings drifted through ancient seas. These species are gone now, erased by extinction, yet they refuse to fade quietly into the past. Their fossils continue to trouble, inspire, and puzzle scientists, challenging our understanding of evolution, climate, and life itself.

Extinction is often imagined as an ending, a final silence. In reality, extinction is also a beginning. It opens questions that may never be fully answered. How did these creatures truly live? Why did they disappear? Were their deaths sudden or slow, inevitable or avoidable? Each extinct species is a fragment of a broken story, and scientists are still trying to piece those fragments together.

This is the story of long-extinct species that still puzzle science, not because we lack fossils, but because nature rarely gives up her secrets easily.

Fossils as Messages Across Deep Time

Fossils are not just stones shaped like bones. They are messages sent across millions of years, preserved by chance and catastrophe. A footprint hardened in mud, a skeleton buried under volcanic ash, a tooth locked in ancient sediment—each is a whisper from a vanished world. Yet these messages are incomplete. Soft tissues decay, behaviors vanish, and ecosystems collapse into scattered clues.

Scientists reconstruct extinct species much like detectives reconstruct crimes without witnesses. They study bone structure to infer muscle strength, tooth shape to guess diet, and chemical signatures to understand climate. Even then, many interpretations remain uncertain. Two scientists can look at the same fossil and imagine very different creatures.

This uncertainty is not a weakness of science but a reflection of reality. Life is complex, and deep time erases details mercilessly. It is within these gaps that the greatest mysteries of extinct species live.

Tyrannosaurus Rex and the Problem of Power

Few extinct animals capture the human imagination like Tyrannosaurus rex. It has been portrayed as a roaring monster, a sluggish scavenger, a feathered predator, and even a surprisingly intelligent hunter. Despite more than a century of study, T. rex remains deeply puzzling.

One of the greatest mysteries lies in its sheer power. Its skull was massive, its teeth as long as bananas, and its bite force among the strongest ever measured in a land animal. But how exactly did it use this power? Some evidence suggests it crushed bone with ease, while other fossils hint at more delicate feeding behaviors.

Its tiny arms raise another enduring question. Were they useless remnants of evolution, or were they strong, specialized tools for gripping prey or aiding in mating? Recent studies suggest they were surprisingly muscular, but their precise function remains unclear.

Even its behavior is debated. Did Tyrannosaurus hunt alone or in groups? Did it care for its young? Fossils provide hints but no definitive answers. T. rex stands as a reminder that even the most famous extinct species can remain enigmatic.

The Gentle Giants of the Ice Age

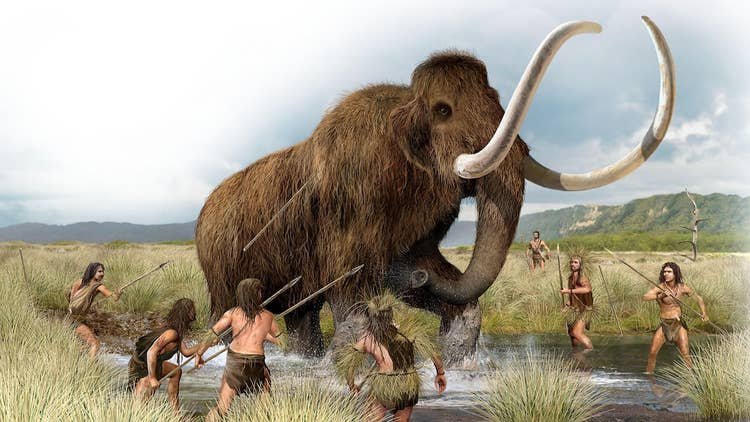

The Ice Age gave rise to some of the most impressive mammals ever to walk the Earth. Mammoths, mastodons, giant ground sloths, and woolly rhinoceroses dominated cold landscapes for thousands of years. Their bones are abundant, their extinction relatively recent, and yet their lives remain shrouded in mystery.

Take the woolly mammoth. Frozen carcasses discovered in Siberian permafrost have preserved hair, skin, and even stomach contents. We know what they ate and what they looked like, but we still debate why they disappeared. Climate change played a role, shrinking their habitat as the Ice Age ended. Human hunting likely added pressure. But why did some populations survive longer than others? Why did mammoths vanish while other large mammals endured?

Giant ground sloths are even more puzzling. Some species stood as tall as elephants and weighed several tons. Their massive claws suggest immense strength, yet their teeth indicate a plant-based diet. How did they move? Were they slow and solitary, or active and social? Their extinction coincides suspiciously with human expansion into the Americas, but direct evidence of widespread hunting is limited.

These Ice Age giants sit at the intersection of natural and human-driven extinction, making them especially difficult to understand.

Saber-Toothed Cats and the Limits of Specialization

The saber-toothed cats, especially Smilodon, are among the most iconic predators of prehistory. Their long, curved canine teeth are unlike anything seen in modern cats, raising immediate questions about how they hunted and fed.

Those enormous teeth were fragile, not suited for bone-crushing. This suggests that saber-toothed cats used precise killing techniques, possibly targeting soft tissues like the throat. Their powerful forelimbs indicate they relied on ambush rather than speed, pinning prey before delivering a fatal bite.

Yet this specialization may have been their downfall. As ecosystems changed and large prey became scarce, saber-toothed cats may have struggled to adapt. Their extinction highlights one of evolution’s most haunting lessons: success in one era can become vulnerability in another.

Despite abundant fossils, including entire skeletons from sites like La Brea Tar Pits, scientists still debate their social behavior, hunting strategies, and the exact reasons for their disappearance.

The Dodo and the Illusion of Simplicity

The dodo is often portrayed as a foolish bird, clumsy and doomed by its own stupidity. This image is deeply misleading. The dodo was a successful species that evolved on the isolated island of Mauritius, free from predators. It had no need to fly and thrived in its environment for thousands of years.

The mystery of the dodo lies not in how it lived, but in how quickly it vanished. Within decades of human arrival, the species was extinct. Hunting, introduced animals, and habitat destruction combined to overwhelm it. Yet we have no complete skeleton from a living dodo, only fragments and artistic impressions.

This lack of data makes reconstructing the dodo’s true appearance and behavior surprisingly difficult. The dodo teaches scientists that extinction can happen rapidly and leave behind a distorted legacy shaped more by myth than evidence.

Megalodon and the Terror of the Ancient Seas

Megalodon, the giant prehistoric shark, is one of the most mysterious predators to have ever existed. Known primarily from enormous fossilized teeth, Megalodon may have grown over fifteen meters long, dwarfing modern great white sharks.

But size alone does not explain its dominance or its extinction. Scientists debate its hunting methods, metabolic needs, and preferred habitats. Did it roam the open oceans or stick to coastal waters? Did it hunt whales actively or scavenge massive carcasses?

Its extinction remains particularly puzzling. Climate change likely altered ocean temperatures and currents, affecting prey availability. Competition from emerging predators may have played a role. Yet no single explanation fully satisfies researchers. Megalodon disappeared, but the oceans it ruled still carry echoes of its presence.

The Enigma of the Neanderthals

Not all extinct species were animals vastly different from us. Neanderthals were close relatives of modern humans, sharing a common ancestor and even interbreeding with Homo sapiens. Their extinction is one of the most emotionally charged mysteries in science.

For decades, Neanderthals were portrayed as brutish and inferior. Modern research has shattered that image. They made sophisticated tools, used fire skillfully, cared for the sick, and likely had language and culture. Genetic evidence shows that many people alive today carry Neanderthal DNA.

So why did they disappear? Were they outcompeted by modern humans? Absorbed through interbreeding? Undone by climate fluctuations? The answer may involve all these factors, woven together in complex ways.

The extinction of Neanderthals forces scientists to confront uncomfortable questions about survival, identity, and what it truly means to be human.

Ancient Insects and the Mystery of Gigantism

Fossils from the Carboniferous period reveal insects of astonishing size. Dragonflies with wingspans over half a meter, millipedes longer than cars, and spiders that would terrify modern observers once thrived on Earth.

Why did insects grow so large, and why did they shrink? The leading explanation involves atmospheric oxygen levels, which were significantly higher hundreds of millions of years ago. Insects breathe through passive systems that work better with abundant oxygen.

Yet this explanation may not tell the whole story. Predation, climate, and plant life likely played roles as well. The disappearance of giant insects remains a puzzle, reminding scientists that life’s limits are shaped by multiple interacting forces.

Marine Reptiles and the Vanished Oceans

The age of dinosaurs was also an age of incredible marine reptiles. Ichthyosaurs, plesiosaurs, and mosasaurs dominated ancient seas, evolving into forms that rival modern whales and sharks in size and efficiency.

Despite extensive fossil records, scientists still debate their physiology. Were they warm-blooded or cold-blooded? How fast did they swim? How deep could they dive? Their extinction, likely linked to the same mass extinction that ended the reign of dinosaurs, raises further questions about the vulnerability of ocean ecosystems.

These marine reptiles challenge assumptions about what reptiles can be and how life adapts to aquatic environments.

Mass Extinctions and the Patterns of Loss

Many long-extinct species vanished during mass extinction events, moments when life on Earth suffered catastrophic losses. The causes of these events include volcanic eruptions, asteroid impacts, climate shifts, and changes in ocean chemistry.

Yet even within mass extinctions, patterns of survival and loss are uneven. Some species endure while others disappear. Understanding why remains one of the most difficult problems in paleontology.

These patterns suggest that extinction is not random. Traits such as adaptability, reproductive strategy, and ecological flexibility may determine survival. But predicting these outcomes remains frustratingly complex.

What Extinct Species Teach Us About the Future

The study of extinct species is not just about the past. It offers warnings and insights for the future. Many extinctions were driven by rapid environmental change, whether natural or human-induced. Today, Earth is experiencing another period of accelerated extinction.

By understanding how species responded to past changes, scientists hope to predict which modern species are most at risk. The puzzles of extinct species become tools for conservation, helping humanity avoid repeating ancient mistakes.

The Emotional Weight of Lost Life

There is an undeniable sadness in studying extinct species. Each represents a unique solution to the problem of survival, erased forever. At the same time, there is awe in realizing how resilient and creative life has been.

Extinct species remind us that the world we know is not permanent. Ecosystems change, climates shift, and dominance fades. Humanity itself is part of this ongoing story, subject to the same forces that shaped and erased countless species before us.

The Unfinished Story of Extinction

Science continues to uncover new fossils, develop new technologies, and refine old theories. Each discovery answers some questions while raising others. The long-extinct species that puzzle scientists do so not because knowledge has failed, but because reality is deeper than we imagine.

Their bones lie silent, but their mysteries speak loudly. They challenge us to think beyond the present, to see life as a fragile and dynamic process, and to approach the natural world with humility.

Extinction is not just an end. It is a question, one that echoes across millions of years, asking whether we are listening carefully enough to learn from the lives that came before us.