For most of human history, Earth was not merely our home but our entire universe. The stars were distant lights, fixed and mysterious, their true nature unknown. Even after astronomy revealed that stars were suns like our own, the idea that planets—especially Earth-like planets—might orbit them remained speculative for centuries. Only in the last few decades has this ancient question shifted from philosophy to science. Today, thousands of exoplanets are known, and among them are a small but astonishing group that appear, at least in broad physical terms, to resemble Earth.

These worlds are not fantasy destinations, nor are they proven homes for life. They are places defined by orbital mechanics, stellar radiation, atmospheric physics, and planetary chemistry. Some are closer than any star beyond the Sun; others lie a little farther but remain well within what astronomers call our “galactic backyard.” Each one challenges our understanding of habitability and forces us to confront a profound possibility: Earth may not be unique in its capacity to host life.

The following five planets stand out not because they are perfect copies of Earth, but because, according to current scientific evidence, they occupy a rare middle ground. They are rocky rather than gaseous, temperate rather than extreme, and situated where liquid water could plausibly exist. In exploring them, we are not just cataloging distant worlds—we are expanding the definition of what a living planet might be.

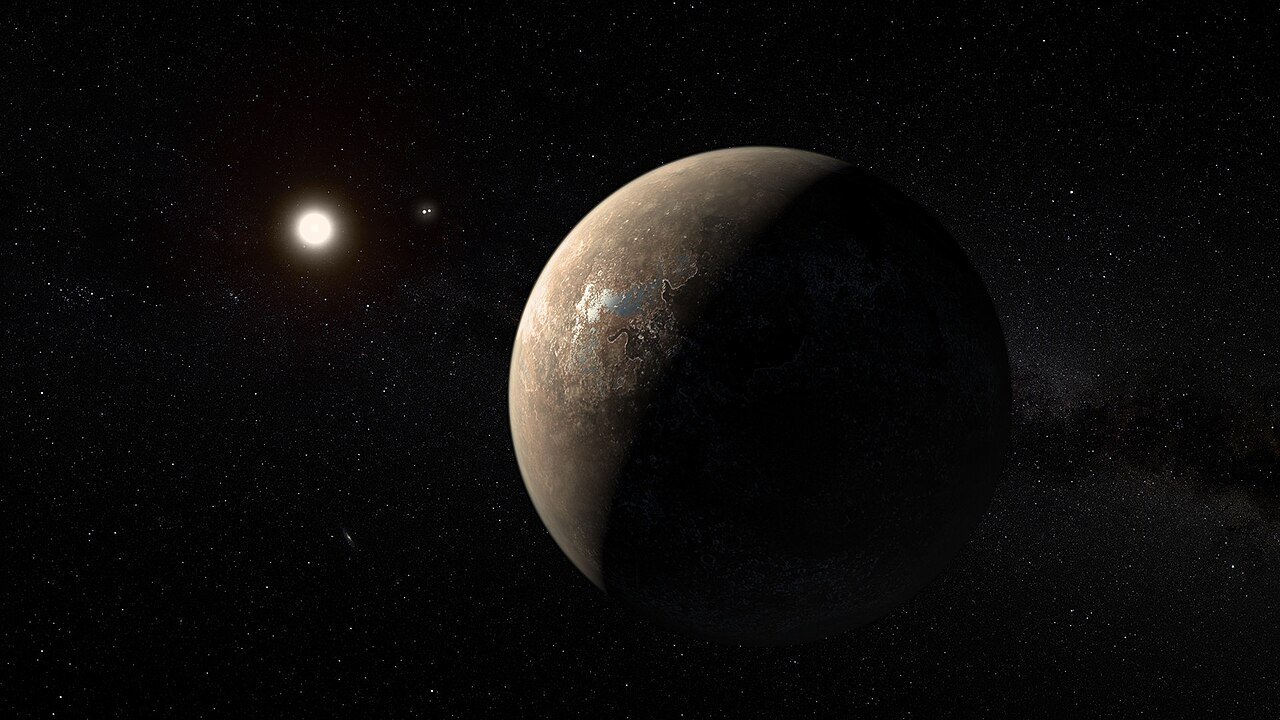

1. Proxima Centauri b: The Nearest Potentially Habitable World

Proxima Centauri b occupies a singular position in the human imagination because of one simple fact: it is the closest known exoplanet to Earth. Orbiting Proxima Centauri, the nearest star to the Sun at just over four light-years away, this planet exists within the same stellar neighborhood that has guided human navigation and storytelling for millennia.

Discovered in 2016 through precise measurements of its star’s motion, Proxima Centauri b is a rocky planet with a minimum mass slightly greater than Earth’s. It orbits its star at a distance much smaller than Earth’s distance from the Sun, but this proximity is necessary because Proxima Centauri is a red dwarf star—cooler and dimmer than the Sun. As a result, the planet receives a level of stellar energy that places it within the star’s so-called habitable zone, where surface temperatures could allow liquid water to exist.

From a purely orbital and energetic perspective, Proxima Centauri b satisfies one of the most critical conditions for Earth-like habitability. Yet the planet’s environment is far from gentle. Red dwarf stars are known for their stellar activity, including frequent flares that emit intense bursts of radiation. Such activity raises serious questions about whether Proxima Centauri b could retain an atmosphere over long periods, especially without a strong magnetic field.

Despite these concerns, the possibility that Proxima Centauri b possesses a substantial atmosphere has not been ruled out. Atmospheric retention depends on multiple factors, including planetary gravity, magnetic shielding, and atmospheric composition. If the planet formed with a thick atmosphere or continuously replenishes it through volcanic activity, it may still maintain surface conditions compatible with liquid water.

What makes Proxima Centauri b emotionally compelling is not just its potential habitability, but its proximity. In cosmic terms, it is practically next door. It transforms the idea of interstellar exploration from a distant dream into a long-term technological challenge. Even if humans never visit Proxima Centauri b, its existence alone reshapes our sense of place, reminding us that Earth-like worlds may be common rather than rare.

2. TRAPPIST-1e: A Temperate World in a Crowded System

The TRAPPIST-1 system represents one of the most remarkable discoveries in modern astronomy. Located about 40 light-years from Earth, this ultracool red dwarf star hosts a compact family of seven known planets, all roughly Earth-sized and all orbiting closer to their star than Mercury does to the Sun. Among them, TRAPPIST-1e stands out as one of the most promising Earth-like candidates.

TRAPPIST-1e is a rocky planet with a size and density similar to Earth’s, suggesting a composition dominated by silicate rock and metal. Its orbit places it squarely within the star’s habitable zone, receiving an amount of stellar energy comparable to what Earth receives from the Sun. Unlike some of its neighboring planets, TRAPPIST-1e is not expected to be excessively hot or cold, making it a particularly attractive target for habitability studies.

One of the most intriguing aspects of the TRAPPIST-1 system is its orbital architecture. The planets are locked in a complex gravitational resonance, which helps stabilize their orbits over long periods. This stability increases the likelihood that TRAPPIST-1e has experienced relatively consistent conditions over billions of years, a key factor for the potential development of life.

As with Proxima Centauri b, TRAPPIST-1e likely experiences tidal locking, meaning one side of the planet permanently faces its star while the other remains in darkness. While this configuration once seemed hostile to life, modern climate models suggest that a sufficiently thick atmosphere or global ocean could redistribute heat effectively, preventing extreme temperature contrasts.

The emotional power of TRAPPIST-1e lies in its context. It is not an isolated world, but part of a planetary community. If one planet in the system is habitable, others may be as well, raising the possibility of multiple life-supporting worlds orbiting the same star. This challenges the long-held assumption that habitable planets are rare and solitary, suggesting instead that nature may favor abundance and variety.

3. Kepler-452b: An Older Cousin of Earth

Kepler-452b occupies a different niche among Earth-like exoplanets. Located about 1,400 light-years away in the constellation Cygnus, it is far more distant than Proxima Centauri b or TRAPPIST-1e. Yet its physical and orbital characteristics have earned it the nickname “Earth’s older cousin.”

Discovered by NASA’s Kepler space telescope, Kepler-452b orbits a star remarkably similar to the Sun in size, temperature, and luminosity. Its orbital period is close to one Earth year, and it resides within the habitable zone of its star, where temperatures could allow liquid water on the surface.

Kepler-452b is larger than Earth, with a radius about 60 percent greater. This places it in a transitional category between Earth-sized rocky planets and larger mini-Neptunes. Whether Kepler-452b is truly rocky or possesses a thick gaseous envelope remains uncertain, but models suggest that a substantial fraction of planets in this size range can still have solid surfaces.

What sets Kepler-452b apart is the age of its star system. The host star is estimated to be several billion years older than the Sun, meaning that Kepler-452b has likely existed in the habitable zone for a longer time than Earth has. If life requires long periods of stable conditions to emerge and evolve, this extended timeline could be significant.

At the same time, stellar evolution introduces complications. As stars age, they gradually become brighter. Kepler-452b may now be receiving more energy than Earth does today, potentially pushing it toward a warmer, more Venus-like state. This possibility underscores an important lesson in planetary science: habitability is not static but evolves over time.

Kepler-452b invites reflection on Earth’s future as well as its past. By studying such planets, scientists gain insight into how long habitable conditions can persist and what factors ultimately limit a planet’s ability to support life. In this sense, Kepler-452b is not just a distant world, but a mirror in which we glimpse possible futures for our own planet.

4. LHS 1140 b: A Dense and Promising Super-Earth

LHS 1140 b is a planet that initially surprised astronomers with its density. Orbiting a red dwarf star about 40 light-years away, this planet is larger and more massive than Earth, placing it in the category of super-Earths. What makes it particularly compelling is that, despite its size, it appears to be rocky rather than gaseous.

Measurements indicate that LHS 1140 b has a high density consistent with a substantial iron core and rocky mantle. This suggests a strong gravitational field capable of retaining a thick atmosphere, even in the face of stellar radiation from its host star. The planet orbits within the habitable zone, receiving an amount of energy that could support liquid water under the right atmospheric conditions.

One of the most intriguing aspects of LHS 1140 b is the nature of its host star. While red dwarfs are often active in their youth, many eventually settle into long periods of relative calm. If LHS 1140 b formed early and survived its star’s more violent phase, it may now exist in a comparatively stable environment.

The planet’s high gravity could have both positive and negative implications for habitability. On one hand, it helps maintain an atmosphere and potentially drive geological activity, such as volcanism, which can recycle nutrients and gases. On the other hand, increased gravity may affect atmospheric pressure and human physiology in ways that would challenge Earth-based life forms.

Emotionally, LHS 1140 b represents resilience. It is a world that appears to have endured harsh early conditions and emerged as a stable, potentially life-supporting planet. In doing so, it expands our understanding of where habitability might arise, suggesting that life-friendly worlds need not be Earth-sized to be Earth-like in function.

5. TOI-700 d: A Quiet Planet Around a Quiet Star

TOI-700 d is one of the most Earth-sized planets discovered within the habitable zone of its star, and it orbits a star that appears unusually calm for a red dwarf. Located about 100 light-years away, this planet has become a benchmark for studying temperate, rocky worlds around low-mass stars.

Discovered by NASA’s Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite, TOI-700 d is similar in size to Earth and receives about the same amount of stellar energy. Its host star is smaller and cooler than the Sun but exhibits relatively low levels of stellar activity, reducing the likelihood of frequent, atmosphere-stripping flares.

Climate models suggest that TOI-700 d could support surface temperatures compatible with liquid water, assuming the presence of an atmosphere. The planet may be tidally locked, but as with other such worlds, atmospheric circulation could moderate temperature extremes between the day and night sides.

What makes TOI-700 d especially valuable is its suitability for future atmospheric characterization. Its transits allow astronomers to analyze starlight filtered through the planet’s atmosphere, potentially revealing the presence of gases such as carbon dioxide, water vapor, or even oxygen.

TOI-700 d embodies a quieter vision of habitability. It is not a world of dramatic extremes or violent stellar behavior, but one that suggests stability and balance. In a galaxy where chaos often dominates, such calm may be one of the most important ingredients for life.

Conclusion: Earth-Like Worlds and the Expanding Horizon of Possibility

These five planets—Proxima Centauri b, TRAPPIST-1e, Kepler-452b, LHS 1140 b, and TOI-700 d—are not confirmed Earth twins. None of them has been shown to possess oceans, forests, or life. Yet each one satisfies key physical criteria that make Earth habitable: a rocky surface, access to energy, and the potential for liquid water.

Together, they tell a larger story. Earth-like planets are not rare anomalies hidden in the depths of the galaxy. They exist nearby, orbiting stars that share our cosmic neighborhood. Their diversity reminds us that habitability is not a single condition but a spectrum shaped by physics, chemistry, and time.

As telescopes grow more powerful and techniques more refined, these worlds will shift from points of light to places with measurable atmospheres and climates. In studying them, humanity takes another step toward answering one of its oldest questions: are we alone, or is life a natural consequence of the universe’s laws?

In the quiet glow of nearby stars, these planets wait—not as destinations yet, but as profound reminders that Earth may be one example among many in a galaxy rich with possibility.