Beneath the hot, sun-beaten terrain of South Texas, where the Gulf winds sweep across scrubland and mesquite, an ancient mystery lay embedded in the earth—bones, shaped by human hands, silent yet resonant with the voices of forgotten people. For decades, archaeologists had noted the curious appearance of modified human bones at various prehistoric sites in this region, but these enigmatic relics remained largely unstudied, cataloged but unexplored, their meanings obscured by time.

It wasn’t until Dr. Matthew S. Taylor, a seasoned bioarchaeologist with deep roots in Texas, decided to take a closer look that these artifacts began to reveal their stories. With a career shaped by childhood wanderings across his grandparents’ Central Texas ranch—where arrowheads and ancient tools seemed to sprout from the soil—Taylor’s fascination with the past ran deep. “The desire to learn more about who made them led me to archaeology,” he reflected, “but I realized that bioarchaeology allowed me to study the people themselves. Ever since, I’ve wanted to reconstruct what their lives were like.”

Published in the Journal of Osteoarchaeology, Taylor’s recent study is the first comprehensive reanalysis of these modified human bones from South Texas. His research focused on twenty-nine artifacts, long curated at the Texas Archaeological Research Laboratory (TARL) at the University of Texas at Austin. These weren’t ordinary remains—they were human bones that bore the unmistakable marks of deliberate alteration, modified with care, precision, and cultural significance.

His work took place under the watchful eye of modern ethical standards. In compliance with the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA), Taylor worked closely with representatives from the Comanche Nation, the Caddo Nation, the Mescalero Tribe, and the Kiowa Tribe—nations with ancestral ties to the region. After extensive consultation, none of the federally recognized tribes made claims to the remains, and the study was allowed to move forward.

The bones themselves, mostly long bones of the arms and legs, showed clear evidence of post-mortem processing. Cut marks, carefully applied with stone tools, indicated that the bones had been defleshed—stripped of soft tissue shortly after death. Then, left to dry under the sun or in the open air, the bones were prepared for an ancient technique known as groove-and-snap. This method involved carving a groove into the bone’s surface to a certain depth, weakening its structure until it could be cleanly snapped into segments. The results were smooth, intentional breaks—evidence of a skilled and practiced hand.

This level of processing was not unique to South Texas; similar techniques have been documented elsewhere in the Americas. But within the context of southern Texas, where bioarchaeological investigations have historically been limited, such findings are rare and illuminating. “Unfortunately, there is relatively little bioarchaeological work on Late Prehistoric peoples in South Texas,” Taylor noted. “Some historical accounts mention the processing of human bodies, but not in the way represented by the artifacts in my article.”

The significance of these modified bones lies not only in their physical features but in what they suggest about the cultural mindset of the people who created them. To modern sensibilities, the idea of shaping human bones into tools or instruments may seem macabre, but in many ancient cultures, human remains carried symbolic power. In some societies, bones were fashioned into war trophies, meant to honor victories and intimidate enemies. In others, they were used in rituals of ancestor worship—physical links to the spirits of revered elders and leaders.

Yet in South Texas, such practices had never been definitively proven—until now. Taylor’s research provides compelling evidence that the prehistoric peoples of this region may have shared ritual traditions seen elsewhere in the Americas, albeit with unique local variations. The bones serve as tangible proof that human remains were not universally considered taboo. On the contrary, they were part of a culturally sanctioned practice, one that reveals a complex relationship between the living and the dead.

One artifact in particular stood out to Taylor—a left humerus, designated 41KL39, which had been transformed into a musical rasp, or omichicahuaztli, a type of instrument known from postclassic Mexican cultures. This wasn’t just a utilitarian tool; it was a sonic artifact, designed to produce sound when rubbed or scraped. Engraved with twenty-nine notches and a distinctive zigzag pattern, the bone showed wear marks indicating frequent use. When played, it would have produced a low, reverberating buzz—a sound perhaps meant for ceremonial use, summoning spirits or accompanying chants under the moonlit sky.

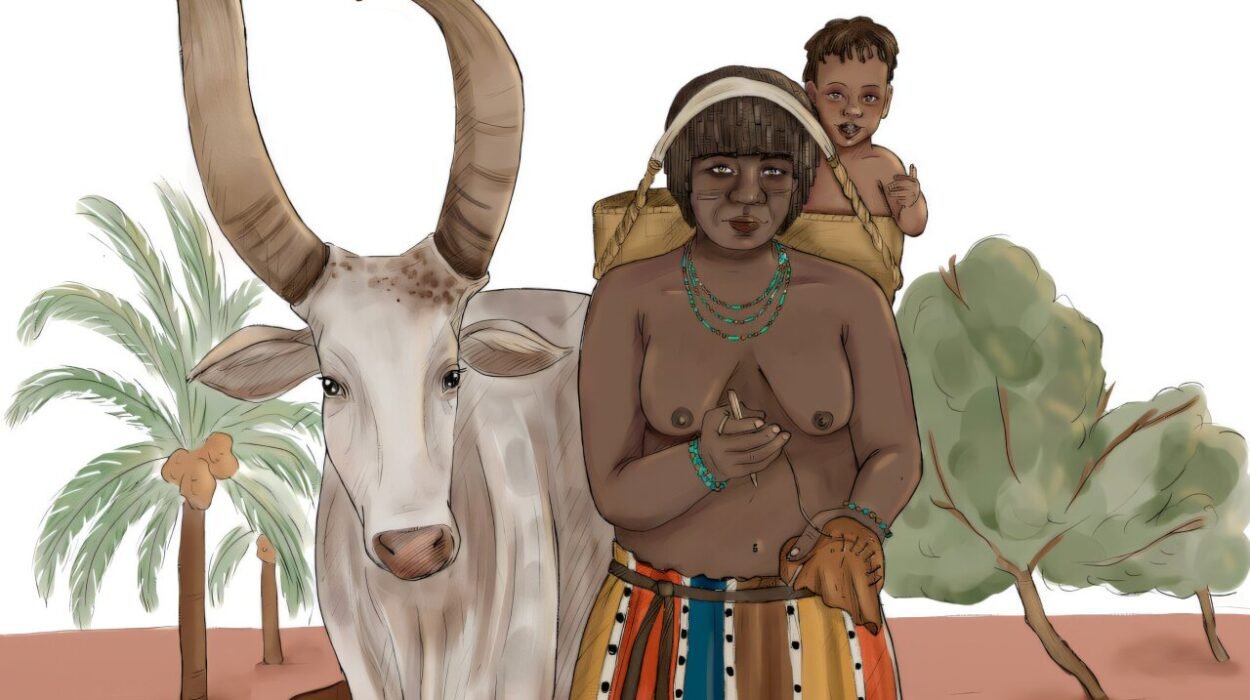

Musical rasps made from human bones are well-documented in Mesoamerica, particularly in regions like Central Mexico, where the Aztecs and their contemporaries used such instruments in religious rites. That a similar artifact was found in South Texas suggests possible cultural diffusion—a movement of ideas, technologies, and beliefs from the great civilizations of Mexico northward along trade routes that may have followed the Gulf Coast.

“There is a hypothesis that a trade route, the Gilmore Corridor, may have run along the Gulf Coast from Mexico to the American Southeast,” Taylor explained. “The similarities between the South Texas and Mexican artifact types is a factor inferring influence, but the musical rasp seems like an attempt at a copy. The one in Texas is made from a humerus, for example, while the ones from Mexico are generally made from femorae.”

This observation adds nuance to the idea of cultural influence—it suggests that while the people of South Texas may have been aware of Mesoamerican musical instruments and ritual practices, they adapted them in a way that fit their own social and environmental context. The choice of bone, the engraving style, and even the sound produced were likely tailored to local traditions, resulting in an artifact that was both familiar and original.

Despite these fascinating findings, questions remain. What was the precise function of these modified bones? Were they used in daily life, or reserved for sacred rituals? Did they serve as personal memorials, tribal emblems, or instruments of war? The lack of direct historical accounts makes definitive answers elusive, but tantalizing clues can be found in early European writings.

One such account comes from Alvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca, a Spanish explorer who was shipwrecked along the Gulf Coast in 1528 and lived among Native peoples for several years. He described a ritual in which the bones of holy men were cremated, mixed with water, and consumed by the living—perhaps as a form of ancestral communion. Though this practice differs from the groove-and-snap technique, it reflects the broader notion that bones held spiritual significance, capable of linking the present with the sacred past.

Other regional practices, such as scalping and body modification, suggest that the human body was not just a biological entity but a canvas for cultural expression. The absence of scalping evidence on the South Texas coast may point to different beliefs about the body, death, and the afterlife. The modified bones analyzed by Dr. Taylor thus serve as rare archaeological windows into these belief systems—material echoes of rituals that once stirred the air with song and smoke.

Importantly, the study also challenges long-standing assumptions about prehistoric coastal societies. Too often, hunter-gatherer groups have been portrayed as culturally stagnant or isolated, especially when compared to the towering cities of the Aztecs or Maya. But the musical rasp, the processing techniques, and the engraved bone fragments suggest a dynamic cultural landscape—one that was responsive to external influences, yet rooted in deeply local traditions.

Taylor’s work is not just a technical analysis of bone modification; it is a deeply human endeavor to reconstruct lives from fragments. Every cut mark, every polished edge, every carved line speaks to intentionality, belief, and the complexities of life and death. His findings underscore the importance of looking beyond the surface of artifacts, to consider what they meant to the people who made them.

The study also highlights the value of collaboration with Indigenous communities. By adhering to NAGPRA and engaging with tribal representatives, Taylor has set a standard for respectful, ethical archaeology—one that honors the descendants of those whose bones now rest in drawers and displays. Their stories, once muted by centuries of dust and neglect, are beginning to speak again through science, art, and history.

As Taylor’s reanalysis demonstrates, the prehistoric peoples of South Texas were not just passive inhabitants of their environment. They were innovators, ritualists, musicians, and cultural participants in a wider network that extended deep into the heart of ancient America. Their modified bones are not grim curiosities but powerful expressions of identity, belief, and connection—relics that remind us that even in the face of death, creativity endures.

From the windswept sands of the Gulf Coast to the quiet halls of TARL in Austin, the bones of South Texas have journeyed long and far. And thanks to the careful eyes and open mind of Dr. Matthew S. Taylor, they are finally beginning to tell their story.

More information: Matthew S. Taylor, An Analysis of Pre‐Columbian Modified Human Bone Artifacts From the Western Gulf Coastal Plain of North America, International Journal of Osteoarchaeology (2025). DOI: 10.1002/oa.3402