From the moment early humans looked up at the glittering expanse of night and wondered what lay beyond, one question has haunted and inspired our species more than any other: Are we alone in the universe? It is a question that bridges science and philosophy, reason and wonder, fact and faith. It speaks to our deepest desires—to belong, to connect, and to understand whether life is a unique miracle or a universal pattern written into the fabric of the cosmos.

Every generation has sought its own answer. Ancient mythologies filled the heavens with gods and spirits. Philosophers imagined infinite worlds populated by other beings. Modern science has replaced myth with measurement, yet the awe remains the same. We now know that the universe is vast beyond imagination, filled with hundreds of billions of galaxies, each containing billions of stars and countless planets. The sheer numbers suggest that life should not be rare—but despite all our searches, no confirmed sign of life beyond Earth has yet been found.

And so the question endures, unresolved and profound. Are we a lonely spark in an infinite dark, or one note in a cosmic symphony of life? The search for that answer has become one of humanity’s greatest scientific, emotional, and existential pursuits.

The Cosmic Perspective

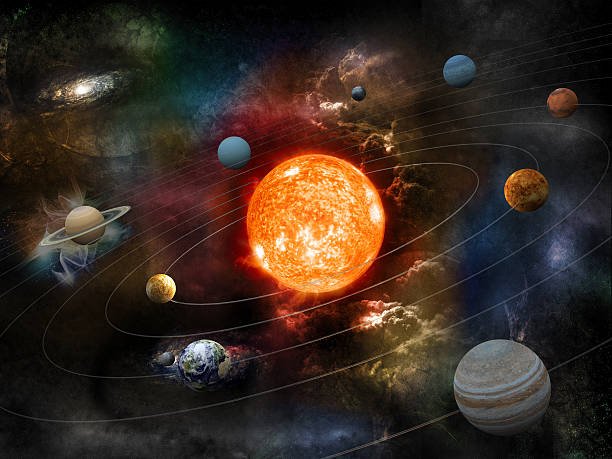

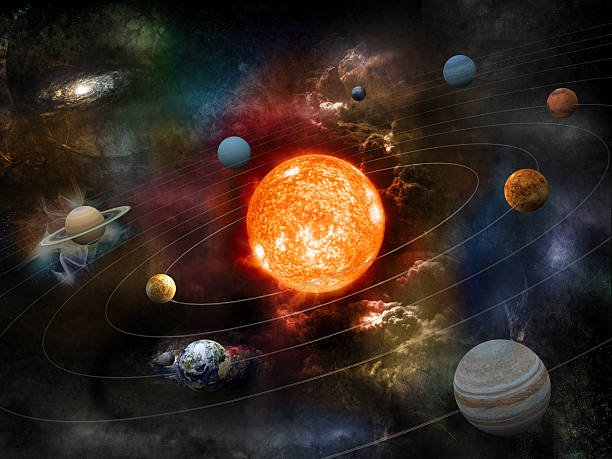

To understand the question of life beyond Earth, we must first grasp the scale of the universe itself. Our planet circles an ordinary star, one among roughly 400 billion in the Milky Way galaxy. Beyond our galaxy lie perhaps two trillion more, stretching across the observable universe. Each star may host its own system of planets—worlds of ice, fire, rock, or gas.

If even a small fraction of those planets are habitable, the potential number of life-bearing worlds becomes staggering. The Milky Way alone could contain billions of Earth-like planets. Yet for all its immensity, the universe remains eerily silent. We have yet to hear a whisper from another civilization. This silence, known as the Fermi Paradox, lies at the heart of the cosmic mystery: if life is common, why have we found no trace of it?

To approach this paradox, science turns to probability, evidence, and imagination—tools that together illuminate the possibilities of life beyond our fragile blue world.

The Birth of Life: Cosmic Chemistry

Life, as we know it, is chemistry given purpose. It arises from the interaction of simple elements—carbon, hydrogen, oxygen, nitrogen—under the right conditions. These elements are among the most abundant in the universe, forged in the hearts of stars and scattered through space by supernovae.

On early Earth, about 3.8 billion years ago, these elements combined in liquid water to form the building blocks of life: amino acids, sugars, and nucleic acids. Lightning, volcanic heat, and ultraviolet radiation provided the energy that drove this chemistry forward. The famous Miller-Urey experiment of 1953 demonstrated that such organic molecules could indeed form spontaneously in conditions mimicking the early Earth’s atmosphere.

If life could arise here, why not elsewhere? The raw materials of life are cosmic, not terrestrial. Organic molecules have been found in interstellar clouds, meteorites, and comets. Even distant moons like Titan harbor complex hydrocarbons in their atmospheres. The seeds of biology, it seems, are scattered across the stars.

The Ingredients of Habitability

For life to emerge and persist, certain environmental factors must align. Chief among them is liquid water—a universal solvent that allows complex molecules to interact. Temperature, atmosphere, energy sources, and chemical stability also play vital roles.

In our Solar System, the so-called habitable zone—the region where liquid water can exist—includes Earth and potentially Mars and some icy moons. Yet habitability is not limited to proximity to the Sun. Worlds like Europa and Enceladus, moons of Jupiter and Saturn, have vast oceans hidden beneath their frozen crusts, heated by tidal forces. There, life might exist in darkness, nourished by chemical energy rather than sunlight, just as microbes thrive around hydrothermal vents on Earth’s seafloor.

This discovery has expanded our imagination. Life may not need a temperate surface or a blue sky. It could flourish in subterranean oceans, under thick ice, or even in the clouds of gas giants. The universe’s possibilities for life are far broader than once believed.

Mars: The Neighbor with Secrets

Mars, our closest planetary neighbor, has long been the prime candidate in the search for extraterrestrial life. Once a world of rivers, lakes, and perhaps shallow seas, Mars today is a cold desert, its atmosphere thin and dry. Yet its surface still bears the scars of flowing water—ancient deltas, riverbeds, and mineral deposits that could have preserved traces of life.

Rovers such as Curiosity, Perseverance, and Zhurong have explored the Martian surface, analyzing rocks and soils for signs of organic molecules. NASA’s Perseverance rover, in particular, is collecting samples that may one day be returned to Earth for detailed study. Some Martian meteorites found on Earth contain structures and chemical signatures that resemble microbial fossils, though the evidence remains inconclusive.

Beneath the surface, Mars may still harbor liquid water, shielded from harsh radiation. If microbes once lived—or still live—there, they may be hidden underground, awaiting discovery. The search for Martian life is not only a quest for biology but also for origins—since any life on Mars might share ancestry with Earth, possibly exchanged through meteorite impacts billions of years ago.

The Ocean Worlds

Beyond Mars, the outer Solar System offers some of the most promising habitats for life. Europa, a moon of Jupiter, is encased in ice but hides a global ocean beneath. Data from the Galileo spacecraft suggest that this ocean contains more water than all of Earth’s combined. Plumes of water vapor have been observed erupting from its surface, hinting that material from the ocean may be accessible for study.

Similarly, Saturn’s moon Enceladus has geysers that spray icy particles and organic compounds into space. Analysis of these plumes reveals the presence of water, salts, and simple carbon-based molecules—ingredients compatible with microbial life. Beneath its frozen shell, hydrothermal vents may provide the same energy-rich environments that sustain life on Earth’s ocean floors.

Even Titan, Saturn’s largest moon, presents fascinating possibilities. Its thick orange atmosphere and methane lakes represent a world chemically rich, though frigid. While life as we know it would struggle in such conditions, some scientists speculate about exotic biochemistries based on methane or ammonia instead of water.

These moons remind us that the conditions for life may be more common than once thought. The universe’s creativity, it seems, far exceeds our imagination.

The Exoplanet Revolution

In the past three decades, astronomy has undergone a revolution. The discovery of exoplanets—planets orbiting stars beyond our Sun—has transformed our understanding of the cosmos. Since the first confirmed detection in 1992, thousands of exoplanets have been catalogued, revealing an astonishing diversity of worlds.

We have found planets larger than Jupiter orbiting scorchingly close to their stars, rocky “super-Earths” with thick atmospheres, and even worlds in binary star systems. Some of these planets reside in their stars’ habitable zones, where temperatures might allow liquid water to exist. Instruments like NASA’s Kepler and TESS telescopes have identified hundreds of such candidates.

The next frontier is not just finding planets but studying their atmospheres for signs of life—what scientists call biosignatures. These may include oxygen, methane, or other gases produced by living organisms. The James Webb Space Telescope (JWST), with its powerful infrared vision, has already begun analyzing the atmospheres of distant exoplanets, seeking the faint fingerprints of biology across the light-years.

The Fermi Paradox: The Silence of the Stars

Given the immensity of the universe and the apparent abundance of habitable worlds, the question arises: where is everyone? This is the essence of the Fermi Paradox, named after physicist Enrico Fermi, who famously asked, “Where is everybody?”

If intelligent life has emerged elsewhere, and if technological civilizations can spread across the galaxy in a few million years—a blink of cosmic time—then we should expect to see evidence of them: signals, probes, or artifacts. Yet we see none.

Many explanations have been proposed. Perhaps life is exceedingly rare. Perhaps intelligent civilizations destroy themselves before mastering interstellar travel. Perhaps they communicate in ways we cannot detect, or choose not to reveal themselves. Some scientists even suggest that we are early—that the universe is still young, and life’s great flowering has yet to come.

This silence may be unsettling, but it also highlights how little we know. The cosmos is vast, and our tools are still crude compared to the distances involved. The absence of evidence, as scientists remind us, is not evidence of absence.

The Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence

For more than half a century, scientists have been listening for whispers from the stars. The Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence, or SETI, uses radio telescopes to scan the skies for artificial signals—structured patterns that nature could not produce. Projects like the Allen Telescope Array and Breakthrough Listen have surveyed millions of star systems, looking for narrow-band transmissions or pulsed beacons that might signify an intelligent origin.

So far, no confirmed signals have been detected. Yet the search continues, expanding into new frequencies and new technologies. Optical SETI looks for laser flashes; other experiments search for waste heat from massive alien technologies, such as hypothetical Dyson spheres that capture stellar energy.

Even if no signal ever arrives, SETI embodies the essence of scientific curiosity. It is an experiment in hope, humility, and patience—a recognition that we are listening to a cosmic ocean, waiting for another voice to answer.

Life Beyond Biology

While the traditional search focuses on carbon-based life, scientists also consider more speculative possibilities. Could consciousness or intelligence arise in forms utterly different from our own? Could life exist as patterns of plasma, quantum networks, or even digital entities?

As technology advances, civilizations might evolve beyond biology, merging with machines or existing as pure information. If such beings exist, their activities may leave subtle traces—technological signatures such as unusual energy emissions, atmospheric pollutants, or megastructures detectable from afar.

The concept of astroengineering—the construction of vast technological works—pushes the limits of imagination. Freeman Dyson proposed that advanced civilizations might encircle their stars with structures to harness energy, detectable as infrared excesses. Others envision galactic-scale computing systems or civilizations that manipulate black holes. If intelligence endures, it could reshape entire regions of space.

These ideas remain speculative, but they remind us that our notion of life may be too narrow. The universe could teem with forms of existence beyond our comprehension.

The Rare Earth Hypothesis

Not all scientists believe that life is common. The Rare Earth hypothesis, proposed by Peter Ward and Donald Brownlee, argues that while microbial life may arise frequently, complex multicellular life like ours may be extraordinarily rare.

This view holds that Earth benefited from a unique combination of factors: a stable orbit in the Sun’s habitable zone, a protective magnetic field, plate tectonics recycling nutrients, a large moon stabilizing our tilt, and the shielding of Jupiter from excessive asteroid impacts. Each condition might be uncommon on its own, and together they could make Earth a cosmic exception.

If this is true, we may indeed be alone—or nearly so—in hosting intelligent beings capable of reflection and technology. Yet even this perspective carries a certain majesty: it underscores the preciousness of life and the responsibility that comes with being its stewards.

The Principle of Mediocrity

Opposing the Rare Earth view is the Copernican principle, or principle of mediocrity, which asserts that there is nothing special about our planet or species. Just as Earth is not the center of the solar system, so too might humanity not be unique. If the laws of physics and chemistry are universal, and if life arose quickly on Earth once conditions permitted, then similar processes should operate elsewhere.

The discovery of extremophiles—organisms that thrive in boiling acid, deep ice, or radioactive environments—has reinforced this belief. Life is astonishingly adaptable. It colonizes every niche on Earth, from volcanic vents to Antarctic glaciers. This resilience suggests that wherever conditions are even marginally favorable, life may find a way.

The principle of mediocrity does not diminish humanity; it situates us within a grand continuum of nature. If life exists elsewhere, it affirms that we belong to a living universe—a cosmos not of isolation, but of connection.

Philosophical and Spiritual Implications

The question “Are we alone?” is not only scientific but deeply existential. If we are alone, then life is an almost miraculous rarity, and consciousness the universe’s way of knowing itself through us. Our responsibility to preserve life becomes immense. If we are not alone, then we are part of a vast cosmic community, connected through the universal laws of matter and mind.

Many thinkers see in this question a mirror for humanity’s self-understanding. It forces us to confront who we are, what we value, and how we define “life” and “intelligence.” Would we recognize alien life if we saw it? Would we understand its motives, communicate its thoughts, or even agree on what it means to exist?

Religious and philosophical traditions have also grappled with this question. Some see the discovery of extraterrestrial life as an expansion of creation’s wonder, others as a challenge to humanity’s uniqueness. Yet across perspectives, the underlying theme remains the same: the search for life beyond Earth deepens our sense of belonging to something vast, mysterious, and shared.

Humanity’s Future Among the Stars

As our technology advances, we are no longer mere observers of the cosmos—we are participants. Our probes have touched other worlds, our telescopes peer into the atmospheres of distant planets, and our radio signals travel outward like ripples in a cosmic pond.

If other civilizations exist, they may already know of us. Our radio and television broadcasts have reached more than a hundred light-years into space, announcing our presence. Whether that is cause for hope or caution is a matter of debate. Some, like physicist Stephen Hawking, warned that contact with advanced civilizations could be dangerous, while others believe it would mark a new epoch in human history—the joining of minds across the stars.

One day, we may not just listen for messages but send our own deliberately—mathematical patterns, digital art, or the DNA code of life itself. The first interstellar probes, propelled by light sails, may one day carry fragments of humanity to nearby star systems. In seeking others, we extend ourselves, affirming that the human story is part of a far greater cosmic narrative.

The Silence That Speaks

Perhaps the silence of the stars is not absence but invitation. It challenges us to listen more deeply, to look with clearer eyes, to imagine more generously. The universe’s vastness need not imply loneliness; it may instead reflect the rarity and beauty of consciousness—the fragile awareness that can look out into the infinite and ask, “Who else is there?”

Even if we never find another civilization, the search itself enriches us. It expands our knowledge, sharpens our humility, and reminds us of the preciousness of life. The very act of asking the question is evidence of our connection to the cosmos, for it shows that the universe has, in some small corner, become aware of itself.

The Living Universe

Whether or not we are alone, one truth is certain: the universe is alive with possibility. Every star is a potential sun, every planet a potential cradle of life. The atoms in our bodies were forged in ancient stars, linking us to the cosmos not metaphorically but physically. To seek other life is to seek our own origins, to trace the continuity between matter and mind, chemistry and consciousness.

If we one day find even the faintest sign of life—a fossilized microbe on Mars, a biosignature in an exoplanet’s atmosphere, or a signal across the void—it will transform humanity’s sense of place. It will prove that life is not a solitary flame but a constellation of lights spread across the cosmic sea.

Until that day, we remain explorers—listening, searching, wondering. The question “Are we alone?” endures not because it lacks an answer, but because it defines what it means to be human. It is the question of a species that looks beyond itself, that hungers to know the unknown, that refuses to accept the limits of the horizon.

The Great Cosmic Question

The universe is vast, silent, and filled with stars. Somewhere, perhaps, a mind not unlike ours looks up at its own night sky and wonders the same thing: Are we alone?

In that shared wondering lies a kind of connection—a bridge across the immensity of space and time. Whether we find others or not, the question unites us with the cosmos. It reminds us that we are part of something immeasurable, ancient, and profoundly beautiful.

We may be alone, or we may not be. But in asking the question, in searching the skies and listening to the silence, we affirm that we are not lost in the dark. We are the universe, contemplating itself—tiny, fragile, yet luminous with curiosity.

And that, perhaps, is the truest answer we have yet found.