Every human culture, from the earliest storytellers around firelight to modern cosmologists armed with satellites and supercomputers, has asked the same haunting question: Where did everything come from? The night sky, with its silent immensity, has always provoked a sense of wonder and unease. Stars appear eternal, yet even they are born and die. Galaxies move apart as though pushed by some unseen force. The universe itself, it seems, had a beginning. But what, if anything, existed before that beginning?

For centuries, religion and philosophy sought to answer this mystery with tales of creation by divine will or eternal cycles of birth and destruction. Then, in the twentieth century, physics joined the conversation—and changed it forever. Scientists discovered that the universe was not static, as once believed, but expanding. Tracing that expansion backward in time led to an extraordinary conclusion: all matter, energy, space, and time were once compressed into an unimaginably hot, dense state. That primordial explosion, the Big Bang, gave birth to the cosmos as we know it.

Yet this revelation raised an even deeper question—what came before the Big Bang? Did time itself begin with that cosmic flash, or did something precede it, setting the stage for creation? To explore this question is to travel beyond the limits of conventional physics, into a realm where the laws of nature themselves may have emerged from chaos. It is an odyssey to the edge of knowledge—a journey into the deep unknown where the universe first stirred into being.

The Birth of an Idea

The Big Bang theory, as it is known today, was not born from myth but from mathematics and observation. In 1927, the Belgian priest and physicist Georges Lemaître proposed that the universe began as a “primeval atom”—a single point containing all the energy and matter that would one day become stars and galaxies. At first, the idea was met with skepticism. The great physicist Albert Einstein preferred a static universe, balanced by a “cosmological constant” that resisted collapse. But nature had other plans.

Two years later, Edwin Hubble observed that distant galaxies were receding from us, their light stretched to longer, redder wavelengths—a phenomenon known as redshift. The universe, Hubble realized, was expanding. Lemaître’s idea suddenly gained traction: if everything is moving apart now, it must once have been closer together, perhaps even condensed into a single, infinitesimal point.

In 1965, cosmic microwave background radiation was discovered—faint afterglow from the early universe, filling all of space with a nearly uniform warmth. This radiation, predicted by Big Bang models, became the “smoking gun” of cosmic origin. The universe had indeed begun with an explosion of energy and matter approximately 13.8 billion years ago.

But while the Big Bang describes what happened after the beginning, it does not explain what caused it. The equations of general relativity, when traced back to the first instant, break down at a singularity—an infinitesimal point of infinite density and zero volume where time, space, and physics as we know them cease to exist. To understand what happened before—or even if “before” has any meaning—we must venture into realms where classical science gives way to quantum gravity, string theory, and cosmic imagination.

The Limits of Time

Time, as we experience it, seems straightforward. It flows from past to future, marked by the ticking of clocks and the beating of hearts. Yet physics reveals that time is not a universal river but a dimension interwoven with space, forming the fabric of space-time. Einstein’s general theory of relativity showed that this fabric bends and stretches under the influence of mass and energy.

At the Big Bang, however, the density and temperature of the universe were so extreme that this fabric may have lost its meaning. The singularity at time zero is not a physical object—it is a mathematical boundary beyond which our equations cannot penetrate. In this sense, asking what happened before the Big Bang may be as meaningless as asking what lies north of the North Pole. Time itself may have begun with the universe.

And yet, this idea—while elegant—leaves us unsatisfied. Could existence truly emerge from nothing? Or is “nothing” simply a state we do not yet understand? Modern physics suggests that even in the absence of matter, quantum fields fill space with restless energy. Perhaps the universe arose not from nothingness, but from a seething quantum vacuum—a timeless foam of possibilities from which space and time crystallized.

The Quantum Seed

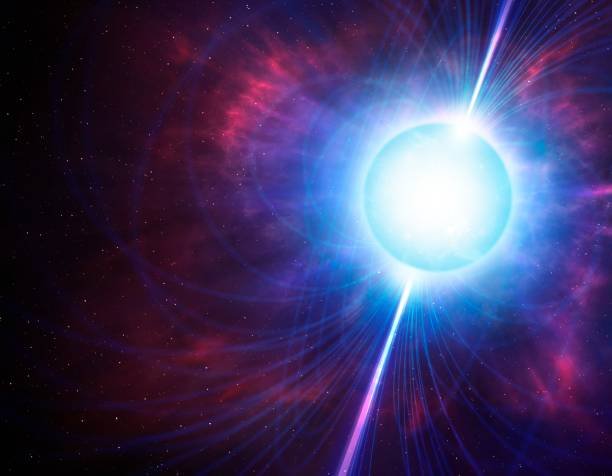

At the smallest scales, the universe is governed not by determinism but by probability. Quantum mechanics describes a world where particles flicker in and out of existence, where uncertainty reigns, and where energy can fluctuate spontaneously. These fluctuations, though ephemeral in ordinary circumstances, could under the right conditions spark something vast.

One leading idea is that the Big Bang was not the creation of energy from nothing, but a quantum transition—from a timeless vacuum state to an expanding universe. In this view, the cosmos emerged as a quantum “tunneling” event, in which the universe jumped from a state of potential to one of reality.

In quantum cosmology, space and time themselves are treated as quantum variables. At the earliest moments—when the universe was smaller than an atom—quantum effects dominated, and the distinction between before and after may have dissolved. The universe may have simply fluctuated into being, like a wave cresting from the quantum sea.

This notion gained mathematical form in the 1980s through the Hartle-Hawking no-boundary proposal. Physicists James Hartle and Stephen Hawking suggested that the universe has no singular beginning, no “edge” in time. Instead, near the Big Bang, time may have behaved like a spatial dimension—smooth and curved rather than abrupt. The universe, in their words, would be “finite but unbounded,” like the surface of a sphere. Just as there is no edge to Earth’s surface where “south” ceases to exist, there would be no moment when the universe first “started.” It simply is.

Inflation and the Birth of Structure

Even if the universe began in a quantum flash, this alone cannot explain its current state—its vast size, uniformity, and delicate structure. For that, we turn to one of the most revolutionary concepts in modern cosmology: cosmic inflation.

Proposed by physicist Alan Guth in 1980, the theory of inflation suggests that in the first fraction of a second after the Big Bang, the universe underwent a period of exponential expansion. Driven by a form of high-energy vacuum known as the “inflaton field,” space itself doubled in size countless times in an instant, smoothing out irregularities and setting the stage for the formation of galaxies.

This burst of inflation not only explains why the universe appears uniform on large scales but also why it is flat, meaning its geometry is neither curved inward nor outward. Tiny quantum fluctuations during this inflationary phase were stretched across cosmic distances, becoming the seeds of all future structure—galaxies, stars, planets, and eventually life.

But where did the inflaton field come from? Was it part of the universe’s original state, or did it arise from an earlier phase of existence? Here, once again, we confront the edge of understanding. Inflation may not have been a singular event, but part of a larger, eternal process.

The Eternal Multiverse

Inflation theory, when extended, leads to a staggering implication: our universe may not be unique. In some versions, inflation never completely ends but continues eternally in different regions of space. Each “bubble” where inflation stops becomes a separate universe, with its own physical constants and laws.

In this vision, our universe is merely one bubble in a vast multiverse—a cosmic foam of endless worlds, each born from quantum fluctuations within the inflationary field. Some may expand forever; others may collapse quickly. Some may harbor familiar physics; others may be utterly alien.

While the multiverse is difficult, perhaps impossible, to test directly, it offers an elegant answer to one enduring puzzle: why do the constants of nature—such as the strength of gravity or the charge of the electron—seem so finely tuned for life? If countless universes exist with different parameters, we naturally find ourselves in one where the conditions happen to allow observers to arise.

Yet the multiverse, while conceptually appealing, raises philosophical questions. Does it truly explain the origin of our universe, or merely shift the mystery to a higher level? If the multiverse exists, what governs its birth? Even infinite worlds must emerge from something—or perhaps, from nothing at all.

Cycles of Creation and Destruction

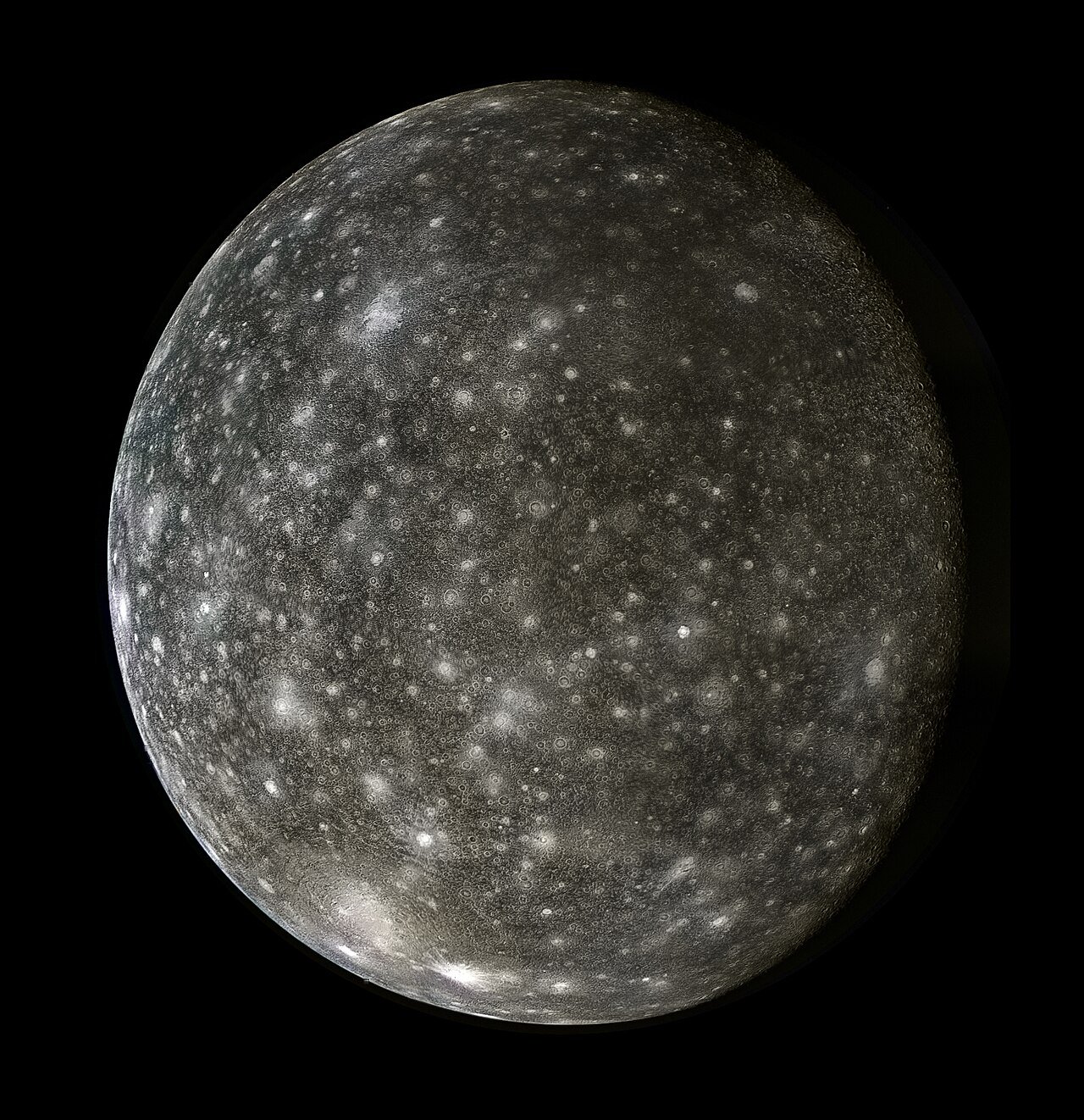

Long before modern cosmology, ancient philosophies imagined the cosmos as cyclic—forever born, dying, and reborn. Intriguingly, modern physics has rediscovered echoes of this idea. Several theories propose that our universe may be one in an eternal series of cosmic cycles, each beginning with a “Big Bang” and ending in a “Big Crunch.”

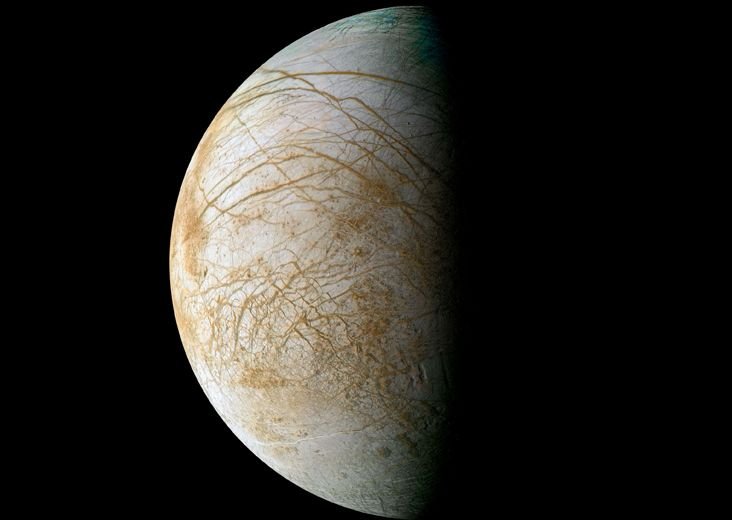

In one version, the universe expands until gravity reverses the process, pulling everything back into a singularity that then explodes anew. In another, known as the ekpyrotic model, inspired by string theory, our universe exists as a three-dimensional “brane” floating in a higher-dimensional space. Periodically, our brane collides with another, releasing immense energy—an event we perceive as a Big Bang.

These cyclic models avoid the problem of a singular beginning. The universe, in this view, has no ultimate origin—it is eternal, oscillating between expansion and contraction like a cosmic heartbeat. Each cycle wipes clean the traces of the last, yet perhaps leaves faint imprints—patterns in the cosmic microwave background that some scientists are now searching for.

The Birth of Space and Time

To understand what might have preceded the Big Bang, we must grapple with the nature of space and time themselves. In everyday life, we think of space as a vast emptiness and time as a continuous flow. But according to general relativity, both are dynamic and interconnected—distorted by energy and matter.

Quantum gravity theories go further, suggesting that space and time are not continuous at all, but discrete, like pixels on a screen. At the smallest scale—the Planck length, about (10^{-35}) meters—space-time may dissolve into a foamy quantum network. If so, the Big Bang was not the creation of space and time, but a phase transition—a change from one quantum state of geometry to another.

Imagine water turning to steam: the molecules remain the same, but their arrangement changes radically. Similarly, before the Big Bang, the universe may have existed in a different phase, one where space and time as we know them did not yet exist. The Big Bang would then mark the moment this hidden, timeless state crystallized into the expanding cosmos we inhabit.

Loop quantum cosmology, a branch of quantum gravity, proposes that the Big Bang was actually a “Big Bounce.” According to this idea, a previous universe contracted to a high density, but quantum effects prevented it from collapsing into a singularity. Instead, it rebounded, giving birth to our current expanding universe. In this scenario, there was no beginning—only transformation.

The Mystery of Nothingness

Even if we accept that the universe could emerge from a quantum fluctuation, we must still ask: why is there something rather than nothing? The question, simple yet profound, touches the limits of both science and philosophy.

Physicists define “nothing” not as absolute emptiness but as a state devoid of particles, fields, and energy. Yet in quantum theory, even this “vacuum” is not truly empty—it seethes with virtual particles that pop into and out of existence. In such a vacuum, energy can fluctuate spontaneously, creating pairs of particles that briefly exist before annihilating each other. Could the universe itself be one such fluctuation, magnified to cosmic scale?

Some physicists, like Alexander Vilenkin, have proposed that the universe could indeed “tunnel” into existence from nothing. In quantum mechanics, tunneling allows systems to cross barriers that would be impassable in classical physics. The universe, he suggests, might have tunneled from a state of absolute nothingness—a timeless void—into a state of expansion. In that case, the universe’s total energy could still be zero: the positive energy of matter and radiation balanced by the negative energy of gravity. From a mathematical standpoint, the universe could emerge from nothing without violating conservation laws.

But others argue that such reasoning merely redefines “nothing.” If quantum laws existed to permit tunneling, then “nothing” already contained potential. True nothingness—utter absence of existence—may be a concept beyond human comprehension, perhaps meaningless altogether.

Echoes of the Beginning

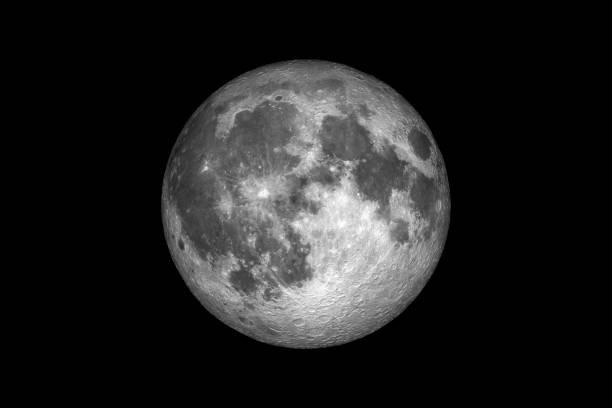

Though we cannot see before the Big Bang, we can study its immediate aftermath. The cosmic microwave background (CMB) is the oldest light in the universe, released when the first atoms formed about 380,000 years after the Big Bang. Tiny variations in this radiation encode information about the universe’s earliest moments—its density fluctuations, composition, and geometry.

Observations from satellites like COBE, WMAP, and Planck have mapped the CMB with exquisite precision, revealing a universe remarkably uniform yet subtly imprinted with quantum fingerprints from its birth. Scientists continue to search for even earlier signals—gravitational waves from the first instants of inflation, ripples in space-time that could carry clues about pre-Big Bang physics.

These cosmic echoes are our best glimpse into the universe’s dawn. They are fossils of creation, faint but enduring, carrying within them the memory of the moment when the cosmos first awoke.

Beyond Physics: The Human Quest

The question of what came before the Big Bang is not merely scientific—it is existential. It reflects our deepest yearning to understand our place in the grand design. Whether the universe began in a singular explosion, an eternal cycle, or a quantum fluctuation, its emergence invites awe. It reminds us that everything we see—every star, planet, and living being—was once contained in a single, blinding spark.

Throughout history, humanity has oscillated between two visions of reality: one rooted in reason and measurement, the other in wonder and imagination. Modern cosmology, at its best, unites them. Its equations describe how the universe evolves; its questions point to mysteries beyond logic.

When we peer back toward the beginning, we confront not only the limits of knowledge but also the nature of being itself. The Big Bang is both a physical event and a philosophical horizon—the boundary between the known and the unknowable. To explore what came before it is to approach the ultimate question: why does the universe exist at all?

The Universe Awakens

If there was a time before time, it may have been filled not with emptiness but with potential—with the ingredients of space, time, and energy poised to burst forth. When the Big Bang occurred, those ingredients took form, and the universe began to expand, cool, and evolve. Within minutes, atoms formed; within millions of years, stars ignited; within billions, life appeared to contemplate its own origins.

In this sense, the Big Bang is not merely an event of the past—it is a continuing process. The universe is still expanding, galaxies are still forming, and consciousness itself is an expression of cosmic evolution. We are, in a profound way, the universe becoming aware of itself.

Perhaps the ultimate answer to what sparked the cosmic dawn lies not in equations alone but in this very awareness. From a quantum fluctuation to sentient beings capable of reflection, the universe has traveled an astonishing path—from nothingness to knowing.

The Infinite Horizon

As our instruments grow more sensitive and our theories more daring, we move closer to glimpsing the prelude to creation. We may never know with certainty what preceded the Big Bang—whether it was a bounce, a multiverse, a timeless quantum field, or something beyond all human conception. Yet in searching for that origin, we engage in something uniquely human: the pursuit of understanding.

Each new discovery brings us a step closer to the moment when the cosmos first stirred. Each unanswered question reminds us that the greatest mysteries are not barriers but invitations—to think, to imagine, to wonder.

The story of the universe before the Big Bang is not just about beginnings; it is about the eternal dialogue between ignorance and insight, between the finite mind and the infinite unknown. The cosmic dawn, whether sparked by chance or necessity, by law or mystery, remains the most profound event in existence—and perhaps, the most beautiful.

The Eternal Flame of Curiosity

The night sky still calls to us as it did to our ancestors, its starlight carrying whispers from the edge of time. Somewhere, beyond the reach of telescopes, beyond the fabric of space itself, lies the answer to the oldest question of all. What came before the beginning?

We may never fully know. Yet the pursuit itself is a kind of creation—the birth of understanding in the human mind. In that sense, every act of discovery, every question asked in wonder, is a small echo of the Big Bang—a spark of light in the darkness.

The universe began in fire, and from that fire emerged stars, planets, life, and thought. And so, as we seek the source of that first flame, we carry it within us. The cosmic dawn was not only the birth of the universe—it was the beginning of the story that continues through us.

We are the children of that explosion, made of its remnants, guided by its light. Before the Big Bang may lie mystery beyond imagination, but within it was born the most extraordinary fact of all: that from chaos came order, from silence came sound, and from darkness came the eternal light of being.