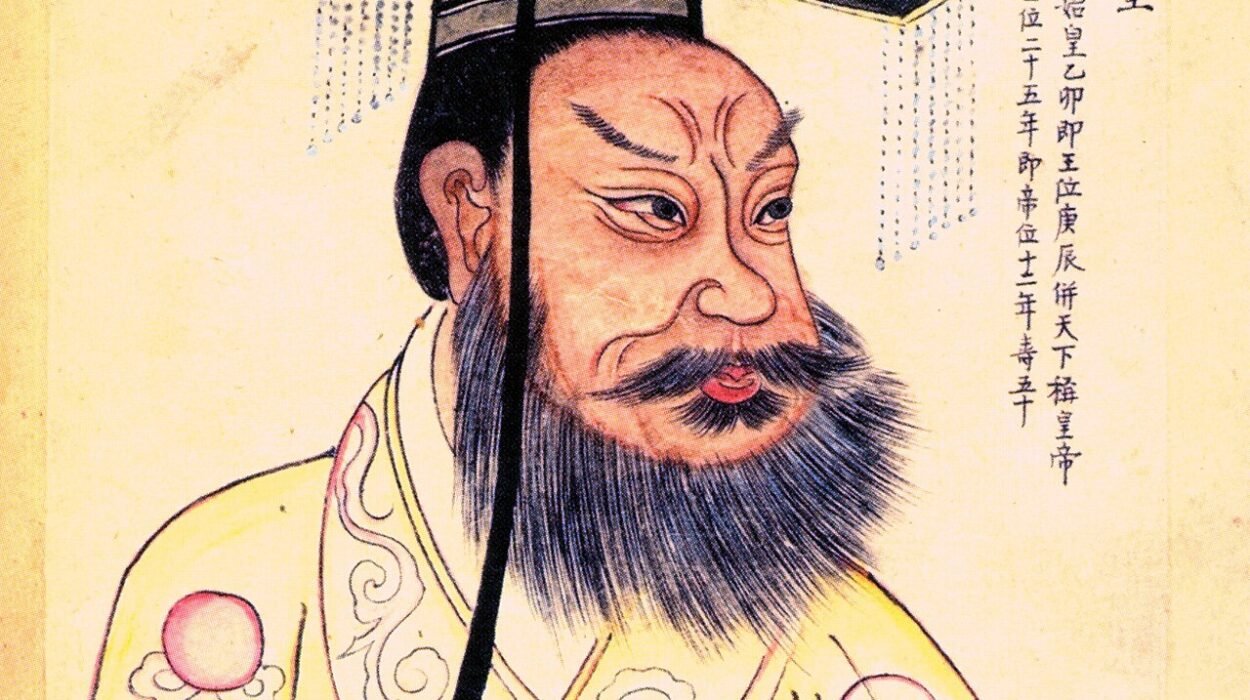

Confucius (551–479 BC) was a Chinese philosopher, teacher, and political figure whose ideas have deeply influenced Chinese culture and East Asian civilization for over two millennia. Born in the state of Lu during a time of social and political turmoil, Confucius developed a philosophy centered on ethics, morality, and social harmony. His teachings, which emphasized respect for tradition, filial piety, and the importance of education, became the foundation of Confucianism, a system of thought that shaped Chinese society and government. Confucius advocated for virtuous leadership, believing that rulers should lead by example to cultivate a just and moral society. Although his ideas were not widely recognized during his lifetime, they gained prominence after his death and were later institutionalized as the state philosophy of imperial China. Confucius’ teachings continue to resonate today, influencing modern thought on morality, governance, and human relationships.

Early Life and Background

Confucius, born as Kong Qiu in 551 BCE in the small state of Lu (modern-day Qufu in Shandong Province, China), is one of the most influential philosophers in Chinese history. His name, “Kong Fuzi,” was later Latinized by Jesuit missionaries to “Confucius.” His ancestry traced back to a noble lineage, but by the time of his birth, his family had fallen on hard times. His father, Kong He, was a military officer of some repute, but he passed away when Confucius was only three years old. His mother, Yan Zhengzai, raised him in poverty, instilling in him values of integrity and perseverance despite their difficult circumstances.

Confucius grew up during a time of great social upheaval in China, marked by the decline of the Zhou Dynasty and the rise of various feudal states. This period, known as the Spring and Autumn period, saw the erosion of central power, leading to widespread moral decay, corruption, and warfare. These tumultuous times deeply influenced Confucius’s thinking and ultimately led him to seek a way to restore order and harmony in society.

From an early age, Confucius showed a thirst for knowledge. Despite his family’s impoverished status, he pursued education with zeal, learning a wide range of subjects, including history, poetry, music, and ritual. This self-driven education laid the foundation for his later teachings. As a young man, Confucius worked in various capacities, including as a shepherd, clerk, and bookkeeper, which gave him practical insights into the lives of ordinary people and the challenges they faced.

Confucius married at the age of 19 and had a son named Kong Li. However, his marriage was not particularly happy, and he eventually separated from his wife, dedicating himself fully to his studies and the pursuit of wisdom. During this time, Confucius also began to gather disciples, teaching them the importance of moral virtues, proper conduct, and the role of the gentleman or “junzi” in society. His teachings emphasized the need for moral integrity, respect for tradition, and the importance of family and societal roles.

In his early years, Confucius sought official positions where he could implement his ideas for social reform. However, his straightforwardness and unwillingness to compromise his principles made it difficult for him to navigate the political landscape of the time. Despite this, he continued to develop his thoughts and teachings, which would later be compiled by his disciples into the Analects, a text that has profoundly shaped Chinese culture and philosophy.

Confucius’s early life was marked by personal challenges and a deep commitment to learning and teaching. His experiences of hardship, coupled with his exposure to the tumultuous state of society, drove him to seek ways to bring about social harmony and moral rectitude. These early influences played a crucial role in shaping the ideas that would later become central to Confucianism.

Philosophical Teachings and Core Concepts

Confucius’s philosophy is rooted in the belief that moral virtue and proper conduct are the foundations of a harmonious society. His teachings emphasize the importance of personal development, social responsibility, and the cultivation of ethical relationships. Central to Confucius’s philosophy are the concepts of “Ren” (benevolence or humaneness), “Li” (ritual or proper conduct), “Yi” (righteousness), “Zhi” (wisdom), and “Xin” (trustworthiness). These five virtues form the core of Confucian thought.

“Ren,” often translated as benevolence or humaneness, is the central virtue in Confucianism. It represents the ideal relationship between individuals and is characterized by compassion, empathy, and love for others. Confucius believed that “Ren” is the foundation of all moral behavior and that it should guide interactions between people. To practice “Ren,” one must consider the well-being of others and act with kindness and respect. Confucius famously said, “Do not do unto others what you do not want done to yourself,” a principle that echoes the Golden Rule found in other ethical traditions.

“Li” refers to the rituals, customs, and norms that govern social behavior. For Confucius, “Li” was not just about performing religious rituals but also about observing the proper conduct in everyday life. “Li” encompasses manners, etiquette, and the roles individuals play within society, such as those of parent, child, ruler, and subject. Confucius believed that adherence to “Li” creates order and harmony in society, as it ensures that everyone knows their place and responsibilities.

“Yi,” or righteousness, is the moral disposition to do what is right, regardless of personal gain or loss. It is closely related to justice and integrity. Confucius taught that a person should act according to what is morally right rather than what is expedient or beneficial to oneself. “Yi” requires individuals to have a strong sense of duty and to act with moral courage, even in difficult situations.

“Zhi,” or wisdom, involves the ability to make sound judgments and decisions based on knowledge and understanding. Confucius valued learning and self-cultivation, believing that wisdom is essential for moral development. A wise person is someone who can discern what is right and just, and who can apply this understanding in their actions and decisions.

“Xin,” or trustworthiness, is the virtue of being honest and reliable. Confucius emphasized the importance of keeping one’s word and being true to one’s promises. Trustworthiness is essential for building and maintaining relationships, both personal and social. For Confucius, a trustworthy person is someone who can be depended upon to act with integrity and consistency.

In addition to these virtues, Confucius also introduced the concept of the “junzi,” or the “gentleman” or “superior person.” The “junzi” is someone who embodies these virtues and serves as a moral example to others. Unlike the “xiaoren,” or “small person,” who is driven by selfish desires and immediate gains, the “junzi” is guided by principles and a sense of duty to others.

Confucius’s teachings were not limited to abstract moral principles but were also practical and applicable to governance and social organization. He advocated for a meritocratic system of government, where rulers and officials were chosen based on their virtue and ability rather than their birth or wealth. Confucius believed that a ruler should lead by example, embodying the virtues of “Ren,” “Li,” and “Yi” to inspire moral behavior in their subjects.

Confucius’s philosophical teachings, centered on the cultivation of virtue and the importance of ethical relationships, have had a profound and lasting impact on Chinese culture and beyond. His ideas have shaped not only personal conduct but also social and political institutions, emphasizing the role of moral integrity in creating a just and harmonious society.

Political Career and Challenges

Confucius’s political career was marked by both ambition and frustration. Despite his desire to implement his philosophical ideas in governance, Confucius faced significant challenges in finding a suitable position where he could influence political affairs. His unwavering commitment to moral principles often put him at odds with the rulers and officials of his time, who were more interested in power and wealth than in ethical governance.

In his mid-30s, Confucius began seeking a position in the government of the state of Lu, hoping to apply his ideas to bring about social and political reform. He initially worked in minor roles, such as managing granaries and overseeing livestock, where he demonstrated his administrative abilities. His reputation as a scholar and moralist grew, and he attracted a group of loyal disciples who were inspired by his teachings.

Confucius’s opportunity to influence politics came when he was appointed as the Minister of Justice in Lu. In this role, he sought to restore moral order and justice, implementing reforms aimed at reducing corruption and promoting meritocracy. Confucius believed that a just society could only be achieved if rulers and officials governed with virtue and set a moral example for their subjects. He emphasized the importance of “Li” in governance, arguing that rulers should observe proper rituals and conduct to maintain harmony and stability.

However, Confucius’s efforts to reform the government of Lu were met with resistance. The ruling class, including Duke Ding of Lu, was reluctant to fully embrace Confucius’s ideas, as they threatened the established power structures and privileges. Confucius’s insistence on moral integrity and his criticism of the corrupt practices of the nobility made him unpopular among those who held power.

One of the most significant challenges Confucius faced during his political career was the conflict between the state of Lu and the neighboring state of Qi. The rivalry between these two states led to a series of political intrigues and power struggles. Confucius advised Duke Ding to focus on strengthening Lu through moral governance and internal reform, but the Duke was more concerned with maintaining power and alliances through military and diplomatic means.

The final straw for Confucius came when the Duke accepted a lavish gift of 80 beautiful women and 120 fine horses from the state of Qi, a gesture intended to distract him from internal affairs. The Duke’s acceptance of this gift, and his subsequent neglect of state matters, deeply disappointed Confucius. He saw it as a betrayal of the principles of “Ren” and “Li” that he had been advocating. Disillusioned by the Duke’s actions and the lack of progress in his reform efforts, Confucius resigned from his position and left the state of Lu.

For the next several years, Confucius traveled through various states in China, seeking a ruler who would be willing to implement his ideas. He visited the states of Wei, Song, Chen, and Cai, among others, offering his services as a political advisor. However, he found little success in these endeavors during his travels, Confucius encountered numerous challenges and setbacks. The rulers he approached were often more interested in consolidating their power through military force or political alliances than in adopting Confucius’s ideals of virtuous rule. Despite his efforts, Confucius found that his vision of governance, rooted in moral principles and the well-being of the people, was not readily embraced by the political leaders of his time.

In the state of Wei, for example, Confucius initially gained some favor with the ruler, Duke Ling. However, the Duke’s primary focus was on expanding his military power and he showed little genuine interest in Confucian ideals. Furthermore, the Duke’s wife, Nanzi, was known for her manipulative influence over state affairs, which further alienated Confucius. While he was treated with respect and courtesy in Wei, Confucius became increasingly disillusioned by the state’s corrupt leadership and ultimately left, realizing that his teachings would not be implemented there.

In other states, Confucius faced similar obstacles. In Song, he narrowly escaped an assassination attempt orchestrated by officials who felt threatened by his presence. In Chen and Cai, he and his disciples were trapped between the two states during a conflict and were forced to endure significant hardships, including a lack of food and basic necessities. Despite these adversities, Confucius remained committed to his mission, using the time in isolation to further refine his thoughts and teachings.

Confucius’s travels through these states were marked by a combination of hope and disappointment. He held onto the belief that if only he could find a ruler willing to listen, he could transform the state into a model of virtue and order. However, the reality he encountered was often far removed from his ideals. The rulers he met were more concerned with their immediate interests and survival in a time of constant warfare and political instability.

Despite his lack of political success, Confucius’s travels were not in vain. During this period, he continued to attract disciples who were drawn to his teachings and his unwavering commitment to ethical principles. These disciples would later play a crucial role in preserving and spreading Confucius’s ideas, ensuring that his philosophy would endure long after his death.

After years of wandering, Confucius eventually returned to his home state of Lu. By this time, he was in his late 60s and had largely given up hope of finding a ruler who would implement his vision of moral governance. Instead, he devoted the remainder of his life to teaching and compiling texts. He spent his final years reflecting on his experiences and working with his disciples to codify his teachings, which would later be known as the Analects.

Confucius’s political career, while ultimately unsuccessful in achieving the reforms he sought, was a critical period in his life. It exposed him to the realities of the political landscape of his time and deepened his understanding of the challenges inherent in governance. These experiences also reinforced his belief in the importance of virtue and moral leadership, ideas that would become central to Confucianism.

Confucius’s challenges and frustrations in the political arena also highlight the broader context of his times. The Spring and Autumn period was one of intense political fragmentation, where power was constantly contested, and moral authority was often secondary to military might. In such an environment, Confucius’s idealism was both his greatest strength and his greatest obstacle. He remained steadfast in his belief that true leadership was rooted in moral integrity, even when faced with overwhelming evidence to the contrary.

In the end, Confucius’s legacy was not defined by his political achievements, but by his teachings and the impact they would have on future generations. His experiences in the political sphere informed his philosophy and provided a concrete example of the challenges of living according to ethical principles in a world often driven by power and self-interest.

Legacy and the Spread of Confucianism

After Confucius’s death in 479 BCE, his teachings were preserved and promoted by his disciples, who compiled his sayings and discussions into what became known as the Analects (Lunyu). This text, along with other works attributed to Confucius and his followers, such as the Book of Rites (Liji), the Book of Documents (Shujing), and the Book of Changes (Yijing), formed the core of what would later be called Confucianism.

Confucianism, as a philosophical system, emphasized the importance of moral virtue, social harmony, and the cultivation of personal character. It advocated for a hierarchical but reciprocal social order, where each individual had a defined role and responsibilities. Central to this order was the concept of “filial piety” (xiao), the respect and reverence for one’s parents and ancestors, which was seen as the foundation of all other social virtues.

During the Warring States period (475–221 BCE), Confucianism competed with other philosophical schools, such as Daoism and Legalism, for influence in Chinese thought and governance. While Confucianism was respected by many intellectuals, it was not immediately embraced by the rulers of the time, who often favored the more pragmatic and authoritarian approaches of Legalism, especially during the Qin Dynasty (221–206 BCE).

However, Confucianism found its greatest political and cultural influence during the Han Dynasty (206 BCE–220 CE). The Han emperors, particularly Emperor Wu (reigned 141–87 BCE), adopted Confucianism as the official state philosophy, establishing it as the foundation of Chinese education, governance, and social values. The establishment of the Imperial Academy in 124 BCE, where Confucian classics were taught and studied, further solidified Confucianism’s central role in Chinese society.

Confucianism’s emphasis on education and moral cultivation became deeply embedded in the fabric of Chinese society. The civil service examination system, which was established during the Sui Dynasty (581–618 CE) and refined during the Tang (618–907 CE) and Song (960–1279 CE) dynasties, was based largely on Confucian texts and principles. This system allowed for the selection of government officials based on merit rather than birth, reinforcing Confucian ideals of governance by the virtuous.

Over time, Confucianism also influenced other East Asian cultures, including Korea, Japan, and Vietnam. In Korea, Confucianism became the dominant ideology during the Joseon Dynasty (1392–1897), where it shaped the country’s social structure, education system, and government. In Japan, Confucianism was introduced during the Asuka period (538–710 CE) and later became integrated with indigenous beliefs and practices, influencing the samurai code of conduct and the Tokugawa shogunate’s governance. In Vietnam, Confucianism played a significant role in shaping the country’s political and social systems, particularly during the Lê Dynasty (1428–1789).

Confucianism’s influence extended beyond politics and education to art, literature, and family life. The Confucian ideal of the “scholar-gentleman” (junzi) became a model for personal conduct and cultural refinement. Confucian values of filial piety, loyalty, and respect for tradition were reflected in Chinese literature, painting, and calligraphy. The Confucian emphasis on harmonious family relationships and ancestor worship became central to Chinese religious practices, blending with other traditions such as Buddhism and Daoism.

However, Confucianism was not without its critics. Some argued that its emphasis on social hierarchy and tradition stifled innovation and perpetuated social inequalities. Others saw Confucianism as too idealistic and impractical in a world where power and survival often took precedence over virtue.

In the modern era, Confucianism has undergone significant reinterpretation and adaptation. The fall of the imperial system in China in the early 20th century, along with the rise of new ideologies such as nationalism, socialism, and communism, led to a decline in Confucianism’s official status. During the Cultural Revolution (1966–1976), Confucianism was harshly criticized as part of the “old culture” that needed to be eradicated.

Despite these challenges, Confucianism has experienced a resurgence in recent decades, both in China and globally. In China, Confucian values have been re-emphasized as part of the country’s cultural heritage and as a counterbalance to the rapid social and economic changes brought about by modernization. Confucius Institutes, established around the world to promote Chinese language and culture, are a testament to the enduring relevance of Confucian thought.

Globally, Confucianism has been recognized for its contributions to philosophy, ethics, and political theory. Its emphasis on moral education, social harmony, and the common good resonates with contemporary discussions about the role of ethics in public life. Confucianism’s insights into human relationships and the responsibilities of leadership continue to offer valuable perspectives in a world facing complex social and ethical challenges.

The Analects and His Teachings

The Analects, or “Lunyu” in Chinese, is the most important and influential text associated with Confucius. It is a collection of sayings and ideas attributed to Confucius and his disciples, compiled posthumously by his followers. The Analects is not a systematic treatise on philosophy but rather a series of dialogues and reflections that provide insights into Confucius’s thoughts on ethics, politics, and human relationships.

The Analects is divided into 20 books, each containing a series of short passages. These passages cover a wide range of topics, including the nature of virtue, the role of the ruler, the importance of education, and the qualities of the ideal person, or “junzi.” While the text can seem fragmented, with some sections appearing contradictory or ambiguous, it reflects the practical and conversational style of Confucius’s teachings.

One of the central themes in the Analects is the concept of “Ren” (benevolence or humaneness). Confucius frequently emphasizes that “Ren” is the most important virtue and the foundation of all moral behavior. For example, Confucius states, “The Master said, ‘Is it not a pleasure, having learned something, to try it out at due intervals? Is it not a joy to have friends come from afar? Is it not gentlemanly not to take offense when others fail to appreciate your abilities?’” (Analects 1.1). This passage reflects Confucius’s belief that true virtue is expressed in joy and acceptance, as well as in a genuine concern for others.

Another key concept in the Analects is “Li” (ritual or proper conduct). Confucius argues that “Li” is essential for maintaining social order and harmony. He often discusses the role of rituals in reinforcing ethical behavior and social norms. For example, he says, “The Master said, ‘To see what is right and not do it is the want of courage’” (Analects 2.3). This highlights the importance of acting according to proper conduct and ethical principles, even when it requires personal sacrifice or courage.

Confucius also places great emphasis on the value of education and self-cultivation. He advocates for continuous learning and personal growth as essential for moral development. He famously states, “The Master said, ‘I have never seen one who loves learning as much as he loves learning. To learn without thinking is labor lost; to think without learning is dangerous’” (Analects 2.15). This reflects his belief that intellectual and moral development go hand in hand and that true wisdom comes from a combination of study and reflection.

The concept of “Yi” (righteousness) is another significant theme in the Analects. Confucius asserts that righteousness involves acting according to moral principles, even when it conflicts with personal interests. He states, “The Master said, ‘The gentleman understands what is moral. The small man understands what is profitable’” (Analects 4.16). This highlights the distinction between moral integrity and opportunism, emphasizing that a virtuous person prioritizes ethical values over personal gain.

Confucius also discusses the qualities of the ideal ruler or leader. He believes that a ruler should lead by moral example, embodying the virtues of “Ren,” “Li,” and “Yi.” He argues that a leader who is virtuous and just will inspire loyalty and respect from their subjects. For instance, he says, “The Master said, ‘To govern is to correct. If you set an example by being correct, who would dare to remain incorrect?’” (Analects 12.17). This underscores Confucius’s belief that effective leadership is grounded in ethical behavior and that rulers have a responsibility to model virtuous conduct.

The Analects also reflect Confucius’s views on the role of the family and social relationships. He places a strong emphasis on “Xiao” (filial piety), the respect and reverence owed to one’s parents and ancestors. He teaches that filial piety is the root of all other virtues and that it should be the guiding principle in family relationships. For example, he states, “The Master said, ‘Filial piety and brotherly respect are the root of all virtue and the source of all moral teaching’” (Analects 1.2). This reflects his belief in the importance of family as the foundation of a well-ordered society.

Overall, the Analects provides a window into Confucius’s thoughts on various aspects of life, including ethics, politics, education, and personal conduct. It emphasizes the importance of moral virtues, proper conduct, and the cultivation of character. The teachings in the Analects have had a profound influence on Chinese philosophy and culture, shaping not only the intellectual traditions of China but also its social and political institutions.

Later Life and Death

Confucius’s later years were marked by a shift from his earlier political ambitions to a focus on teaching and preserving his philosophical ideas. After his return to Lu, he settled into a quieter life, dedicating himself to teaching and working with his disciples. This period of his life was characterized by a deepening of his philosophical insights and a commitment to ensuring that his teachings would be preserved for future generations.

During his final years, Confucius continued to travel and teach, although he was no longer seeking political positions or reforms. Instead, he focused on passing on his wisdom to his disciples and compiling the texts that would become central to Confucianism. His disciples played a crucial role in recording his teachings and ensuring that they would be preserved. They collected his sayings, dialogues, and reflections, which were later compiled into the Analects (Lunyu), a text that would become foundational to Confucian philosophy.

Confucius’s health began to decline in his later years. He suffered from various ailments and his physical condition worsened over time. Despite his declining health, he remained committed to his work and continued to engage with his disciples and students. He used his remaining time to reflect on his life’s work and to impart final lessons to his followers.

In 479 BCE, Confucius passed away at the age of 72. His death marked the end of an era but also the beginning of a legacy that would endure for centuries. Confucius was mourned by his disciples and respected by those who had come to appreciate his teachings. His burial took place in his hometown of Qufu, where a memorial to him was erected, and his descendants continued to honor his memory.

After Confucius’s death, his teachings gained increasing recognition and influence. The establishment of Confucianism as the dominant philosophical and ethical system in China during the Han Dynasty (206 BCE–220 CE) helped to solidify his legacy. The teachings of Confucius were integrated into the fabric of Chinese society and governance, shaping the country’s educational, political, and social institutions.

Confucius’s influence extended beyond China, impacting other East Asian cultures such as Korea, Japan, and Vietnam. His ideas on morality, governance, and social harmony became central to the intellectual traditions of these countries. Confucianism’s emphasis on virtue, education, and social responsibility continued to resonate with people across different cultures and historical periods.

In modern times, Confucius’s teachings have experienced a resurgence as part of a broader reevaluation of China’s cultural heritage. Confucian values have been reinterpreted in light of contemporary issues, and the study of Confucian philosophy remains an important field of inquiry. Confucius’s emphasis on moral integrity, social harmony, and the cultivation of character continues to offer valuable insights for addressing ethical and social challenges in the modern world.

The legacy of Confucius is not only found in the preservation of his teachings but also in the enduring impact of his ideas on Chinese culture and beyond. His life and work have left an indelible mark on the development of philosophy, ethics, and social thought, making him one of the most influential figures in the history of human thought.

Impact on Chinese Culture and Society

Confucius’s impact on Chinese culture and society has been profound and enduring. His ideas have shaped not only the intellectual traditions of China but also its social, political, and cultural institutions. Confucianism, as articulated by Confucius, has influenced various aspects of Chinese life, including governance, education, family relationships, and ethical conduct.

One of the most significant contributions of Confucius is his influence on the structure and function of the Chinese state. During the Han Dynasty (206 BCE–220 CE), Confucianism was adopted as the official state ideology, shaping the principles of governance and administration. The civil service examination system, established during the Sui Dynasty (581–618 CE) and refined during the Tang (618–907 CE) and Song (960–1279 CE) dynasties, was based largely on Confucian texts and principles. This system allowed for the selection of government officials based on merit and knowledge of Confucian classics, rather than hereditary privilege or wealth. This meritocratic approach helped to promote social mobility and ensure that government officials were well-versed in ethical and administrative principles.

Confucianism’s emphasis on education and self-cultivation also had a profound impact on Chinese society. Confucius advocated for continuous learning and personal development as essential for moral and intellectual growth. This focus on education became a cornerstone of Chinese culture, with Confucian ideals shaping the curriculum and methods of instruction in schools and academies. The importance of education in Chinese society is reflected in the high value placed on scholarly achievement and intellectual pursuit.

Family relationships and social hierarchy are other areas significantly influenced by Confucian thought. The concept of “filial piety” (xiao) emphasized respect for one’s parents and ancestors, and this value became a fundamental aspect of Chinese family life. Confucian teachings on family roles and responsibilities helped to define the structure of Chinese households and social interactions. The emphasis on “Ren” (benevolence) and “Li” (ritual propriety) guided interpersonal relationships, promoting harmony and respect within families and communities.

Confucianism’s impact extended to art, literature, and cultural practices. Confucian values of propriety, harmony, and moral integrity were reflected in Chinese art forms, including painting, calligraphy, and literature. Confucian ideals also influenced cultural practices such as ancestor worship and ceremonial rites, which became integral to Chinese religious and social life.

The influence of Confucius’s teachings can also be seen in the way Chinese society approaches ethical and moral issues. Confucian ethics continue to shape discussions on topics such as governance, social responsibility, and personal conduct. The principles of “Ren,” “Li,” and “Yi” remain relevant in contemporary China, where they are often invoked in discussions about ethical behavior, social harmony, and the role of leadership. Confucian values continue to be integral to public discourse and cultural practices, demonstrating their lasting influence on Chinese society.

Confucius’s emphasis on moral self-cultivation and virtuous leadership has also impacted Chinese philosophy and thought beyond the political realm. His teachings have inspired a rich tradition of commentary and interpretation, with scholars and philosophers throughout Chinese history engaging with Confucian ideas and expanding upon them. This ongoing engagement with Confucianism has contributed to the development of various philosophical schools and intellectual movements, enriching China’s cultural heritage.

In addition to its influence on Chinese society, Confucianism has made significant contributions to East Asian cultures more broadly. In Korea, Confucian principles were adopted during the Joseon Dynasty (1392–1897) and became deeply embedded in the country’s social structure, education system, and government. Confucian values shaped the Korean class system, family relationships, and moral conduct, leaving a lasting imprint on Korean culture.

In Japan, Confucianism was introduced during the Asuka period (538–710 CE) and became integrated with indigenous beliefs and practices. Confucian ideas influenced the samurai code of conduct and the governance of the Tokugawa shogunate, contributing to Japan’s unique blend of Confucian and Shinto traditions.

In Vietnam, Confucianism played a crucial role in shaping the country’s political and social systems, particularly during the Lê Dynasty (1428–1789). Confucian principles guided the governance and administrative practices of the Vietnamese state, and the emphasis on education and moral conduct became central to Vietnamese culture.

Confucianism’s influence has also extended to the modern world. In recent decades, there has been a resurgence of interest in Confucian ideas, both in China and globally. In China, Confucian values have been re-evaluated as part of the country’s cultural heritage and as a counterbalance to the rapid social and economic changes brought about by modernization. The establishment of Confucius Institutes around the world reflects the enduring relevance of Confucian thought and its appeal to contemporary audiences.

Confucianism’s emphasis on ethical behavior, social harmony, and the cultivation of character continues to resonate with people across different cultures and historical periods. The principles of Confucianism offer valuable insights for addressing contemporary issues related to governance, education, and personal conduct. As societies grapple with complex social and ethical challenges, the teachings of Confucius provide a framework for understanding and navigating these issues.

Influence on East Asian Philosophy and Culture

Confucius’s teachings did not remain confined to China but spread widely throughout East Asia, profoundly influencing the philosophical, cultural, and social landscapes of Korea, Japan, Vietnam, and beyond. The impact of Confucianism on these regions is significant, shaping their historical development and continuing to resonate in contemporary times. The spread of Confucian thought underscores its universality and adaptability, allowing it to take root in different cultural contexts while maintaining its core principles.

In Korea, Confucianism was introduced during the Three Kingdoms period (57 BCE–668 CE) and became more deeply ingrained during the Goryeo Dynasty (918–1392 CE). However, it was during the Joseon Dynasty (1392–1897 CE) that Confucianism reached its peak influence. During this period, Confucianism was adopted as the state ideology, shaping the political, social, and educational systems of Korea. The civil service examination system, modeled after the Chinese system, was implemented to select government officials based on their knowledge of Confucian texts, thereby ensuring that the governance of the state was guided by Confucian principles.

Confucian values permeated Korean society, influencing family structures, social relationships, and cultural practices. The emphasis on filial piety, respect for elders, and moral integrity became central tenets of Korean life. Confucian rituals and ceremonies, such as ancestor worship and rites of passage, were widely practiced and became integral to Korean culture. The influence of Confucianism extended to education, where the study of Confucian classics was considered essential for intellectual and moral development. The establishment of Confucian academies, known as Seowon, played a crucial role in promoting Confucian learning and maintaining its influence in Korean society.

In Japan, Confucianism was introduced during the Asuka period (538–710 CE) and became intertwined with native Shinto beliefs and practices. The influence of Confucianism grew during the Tokugawa shogunate (1603–1868), when it was used to reinforce the hierarchical social order and promote social harmony. The samurai class, in particular, adopted Confucian ideals of loyalty, duty, and moral rectitude, which were integrated into the bushido, or the way of the warrior. Confucianism also shaped the education system in Japan, with the study of Confucian texts being an essential part of the curriculum for scholars and officials.

The impact of Confucianism in Japan extended beyond the samurai class and influenced broader aspects of Japanese society, including governance, family life, and ethical conduct. The Tokugawa shogunate used Confucian principles to justify its rule and maintain social order, emphasizing the importance of loyalty to one’s superiors and the cultivation of personal virtue. Confucianism also influenced Japanese literature, art, and philosophy, contributing to the development of a distinct Japanese Confucian tradition.

In Vietnam, Confucianism was introduced during the Chinese domination of the region and became firmly established during the Lê Dynasty (1428–1789). Like in China and Korea, Confucianism in Vietnam became the guiding ideology for governance, education, and social conduct. The Vietnamese adopted the Chinese-style civil service examination system, which emphasized Confucian learning as the path to government service. Confucianism also influenced the structure of Vietnamese society, with a strong emphasis on hierarchy, filial piety, and the moral responsibilities of individuals within the family and the state.

Confucian values and rituals became deeply embedded in Vietnamese culture, influencing everything from family relationships to state ceremonies. The Confucian ideal of the scholar-official became a model for the educated elite in Vietnam, who were expected to embody the virtues of loyalty, integrity, and moral leadership. Despite various historical challenges, including periods of foreign rule and internal strife, Confucianism remained a central part of Vietnamese cultural identity.

The influence of Confucius on East Asian philosophy and culture is also evident in the way Confucian ideas have been adapted and interpreted in different contexts. Each region that adopted Confucianism did so in a way that reflected its unique cultural and historical circumstances. In Korea, for example, Confucianism was blended with indigenous shamanistic practices and Buddhist traditions, creating a distinct Korean Confucianism. In Japan, Confucianism was integrated with Shinto and Buddhist beliefs, influencing the development of Japanese ethics and aesthetics.

In modern times, the legacy of Confucius continues to be felt across East Asia. Confucian principles are still invoked in discussions about ethics, education, and governance. In China, there has been a renewed interest in Confucianism as part of a broader effort to reconnect with traditional Chinese culture and values. Confucian ideas have also been promoted internationally through institutions like the Confucius Institutes, which aim to spread Chinese language and culture around the world.

The enduring influence of Confucius in East Asia is a testament to the universal appeal and adaptability of his teachings. Confucianism has provided a moral and philosophical framework that has helped shape the development of East Asian civilizations and continues to offer insights into contemporary issues related to ethics, social harmony, and personal conduct. Through its influence on East Asian philosophy and culture, Confucianism has become one of the most significant intellectual traditions in the world.