Imagine standing at the edge of a black sky rippling with stars. Somewhere beyond that veil, light-years away, lie distant galaxies—worlds that might harbor oceans, alien skies, and the echoes of other lives. The universe stretches endlessly in every direction, a vast ocean so immense that even light, the fastest thing in existence, takes billions of years to cross it. For centuries, humans have looked at that infinity and wondered: Is there a shortcut?

That question—impossible, daring, and beautiful—has given birth to one of the most fascinating ideas in modern physics: the wormhole.

A wormhole, in theory, is a bridge through spacetime. A tunnel connecting two distant points in the universe. Enter one mouth, and you might emerge light-years away in an instant, defying the slow crawl of light and time. It’s the ultimate cosmic loophole, the dream of interstellar travel made real.

But could such a thing actually exist? And more daring still—could we ever travel through one?

The answer lies at the intersection of science and imagination, where physics bends and our deepest human desires to explore the unknown collide.

The Fabric of Spacetime

To understand wormholes, we first have to understand what they tunnel through: spacetime itself.

Einstein’s general theory of relativity revealed that space and time are not separate entities, but a single four-dimensional fabric—flexible, elastic, and alive. Every massive object, from a pebble to a planet to a galaxy, warps this fabric around it. We perceive that warping as gravity.

When you drop a ball on a trampoline, it creates a depression. Roll a marble nearby, and it spirals inward, drawn by the curve. This is how gravity works—not as a mysterious pull across empty space, but as geometry itself.

Now imagine bending that fabric even more. Suppose you fold the trampoline so that two distant points touch. If you could punch a tunnel connecting them, you’d have a shortcut through spacetime—a wormhole.

In essence, a wormhole is a tunnel carved into the geometry of the universe. Its mouths could open in two separate places: across a room, across a galaxy, or across different universes altogether.

This idea might sound like science fiction, but its roots are firmly grounded in Einstein’s equations.

Einstein’s Legacy and the Birth of Wormholes

The first hint of wormholes emerged in 1916, just one year after Einstein published his general theory of relativity. A German physicist named Karl Schwarzschild discovered a solution to Einstein’s equations that described a spherical, non-rotating mass—what we now know as a black hole.

But hidden within his math was a strange possibility—a connection between two regions of spacetime. Later, in 1935, Einstein himself, working with Nathan Rosen, revisited this idea. They found that the equations of general relativity allowed for a “bridge” between two points in spacetime. This structure became known as the Einstein–Rosen bridge, the first theoretical description of a wormhole.

At first, it seemed that nature might truly allow such shortcuts. But there was a problem. The Einstein–Rosen bridge was unstable—it would collapse the instant anything tried to pass through it. In other words, the cosmic door would slam shut before any traveler could enter.

Still, the seed was planted. For decades, scientists and dreamers would return to it, refining the equations, imagining new kinds of wormholes, and daring to ask whether they could somehow be kept open.

The Strange Marriage of Black Holes and Wormholes

To imagine a wormhole, it helps to picture a black hole. A black hole is an object so dense that its gravity bends spacetime infinitely inward. Nothing—not even light—can escape its pull. But if black holes represent the ultimate trap, wormholes represent the opposite: the ultimate escape route.

In some theoretical models, a wormhole could link a black hole with a “white hole”—a hypothetical mirror object that spews matter and energy outward instead of pulling them in. You could fall into a black hole and emerge from a white hole somewhere else in the universe—or even in another universe entirely.

This picture, however, runs into major problems. For one, white holes have never been observed, and there’s no known process that could create them. Even more critically, real black holes are far from calm—they’re violent, energetic regions surrounded by radiation and matter so hot it tears atoms apart. Anything approaching such a region would be vaporized long before reaching its heart.

Yet, not all hope is lost. Some solutions in general relativity suggest wormholes could exist without being tied to black holes at all.

The Morris-Thorne Breakthrough

In 1988, physicists Kip Thorne and Michael Morris—pioneers of gravitational theory and consultants for the film Interstellar—set out to answer a daring question: could a wormhole exist in a way that would allow a human to safely travel through it?

Their work led to a groundbreaking insight. While ordinary matter could never keep a wormhole open (it would collapse under gravity), there might be another way: using exotic matter.

Exotic matter isn’t the stuff we know—atoms, electrons, or photons. It’s a hypothetical form of energy with negative mass or negative energy density. Instead of pulling things together like gravity normally does, exotic matter would push outward, counteracting gravitational collapse.

If enough of this negative energy could be stabilized along the throat of a wormhole, it might theoretically prevent it from pinching off—creating a traversable wormhole.

In other words, wormholes are not forbidden by physics—but keeping them open requires something nature may or may not provide.

Exotic Matter and Quantum Shadows

The idea of exotic matter might sound fantastical, but there are real physical effects that hint at its possibility. One comes from quantum mechanics—the mysterious Casimir effect.

In the Casimir experiment, two uncharged metal plates placed extremely close together in a vacuum experience an attractive force. This happens because quantum fluctuations—the ghostly energy that fills “empty” space—are slightly different between the plates than outside them, creating a pressure imbalance. In this narrow gap, the energy density can actually be negative relative to the outside vacuum.

This doesn’t mean we can build wormholes in the lab (not even close), but it proves that negative energy densities can exist in nature, at least in tiny, fleeting amounts.

Could the universe somehow magnify this quantum effect on cosmic scales? Could advanced civilizations—far beyond our technology—harness negative energy to engineer wormholes?

We don’t know. But physics does not outright forbid it.

The Journey Through the Throat

Suppose, for a moment, that a traversable wormhole existed. What would traveling through it be like?

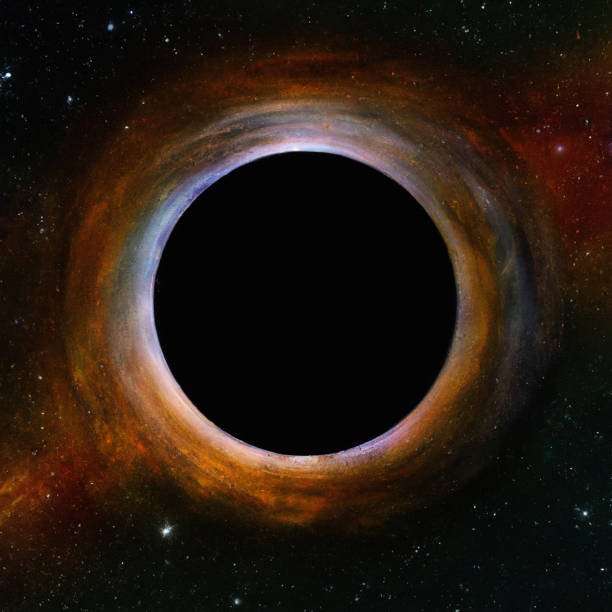

Imagine stepping into a shimmering sphere floating in space, a dark vortex swirling at its heart. From the outside, it might look like a sphere of distorted stars, as if space itself were being bent around an invisible lens.

You approach the entrance—the mouth—and cross an invisible threshold. Instantly, the universe around you warps. Light twists. Time stretches. Gravity becomes meaningless. You are inside the throat of the wormhole—a tunnel of curved spacetime connecting two distant points.

It might feel like floating through a cosmic aurora, space itself flowing past in waves of light and shadow. Within seconds—or less—you emerge at the other mouth, stepping into another galaxy, another star system, another age.

From a traveler’s perspective, almost no time has passed. Yet, to an outside observer, years or even centuries might have gone by. Time dilation, relativistic effects, and quantum uncertainties would all come into play.

It’s a vision that captures the human imagination—a cosmic doorway to everywhere and everywhen.

But behind this beauty lurk dangers unlike anything we can conceive.

The Dangers of the Journey

Wormholes, if they exist, are not gentle passages through space. They are violent distortions of spacetime, surrounded by extreme gravitational tides. A traveler approaching one might experience spaghettification—being stretched and torn apart by tidal forces long before reaching the throat.

Even if the wormhole were somehow stabilized, it would still be bathed in intense radiation. Quantum effects near its surface could create bursts of energy capable of destroying anything that tries to enter.

Then there’s the issue of feedback instability. As light passes through a wormhole, it can reflect back and forth inside it, amplifying its energy until it tears the wormhole apart. To make one traversable, it would have to be shielded, balanced, and maintained with an unimaginable level of precision.

Finally, the problem of causality arises. A traversable wormhole could, in theory, act as a time machine. By moving one mouth relative to the other—say, at near-light speed—you could create a time difference between the two ends. Traveling through such a wormhole might allow someone to arrive before they left, violating the natural flow of cause and effect.

This leads to paradoxes—the infamous “grandfather paradox,” where someone could travel back and prevent their own existence. Most physicists suspect that nature forbids such paradoxes through mechanisms we don’t yet understand. As Stephen Hawking once suggested, there may be a “chronology protection conjecture”—a kind of cosmic censorship preventing time travel via wormholes.

In other words, even if wormholes can exist, the universe may have built-in safeguards to keep them from being used in ways that violate reality.

The Quantum Gravity Connection

At the deepest level, wormholes sit at the crossroads of two great theories: general relativity and quantum mechanics. Relativity describes the large-scale geometry of space and time; quantum mechanics governs the microscopic dance of particles and energy.

These two theories, though both extraordinarily successful, are fundamentally incompatible. Reconciling them into a single framework—a theory of quantum gravity—is one of the grandest challenges in modern physics.

Some physicists believe that understanding wormholes could be the key. In fact, in certain formulations of string theory and quantum gravity, wormholes naturally emerge as part of spacetime’s quantum structure.

One fascinating idea is that tiny, microscopic wormholes—sometimes called “quantum foam”—may constantly form and vanish at the Planck scale, far smaller than atoms. If true, the fabric of the universe is not smooth, but frothy and interconnected, filled with minuscule tunnels linking spacetime points.

Another profound hypothesis, called ER = EPR, proposed by physicists Juan Maldacena and Leonard Susskind, suggests that wormholes (Einstein–Rosen bridges, or “ER”) and quantum entanglement (Einstein–Podolsky–Rosen correlations, or “EPR”) might be two sides of the same coin.

In this view, every pair of entangled particles is connected by a tiny wormhole. The universe, at its most fundamental level, might be a vast web of entangled connections—a cosmic network of microscopic wormholes stitching reality together.

If that’s true, then wormholes are not just speculative constructs—they’re part of the deep quantum architecture of existence.

Building a Wormhole: The Engineering of the Impossible

Let’s imagine humanity in the far future—a civilization that has mastered quantum gravity, controls energy on cosmic scales, and bends spacetime as easily as we now manipulate electricity.

Could we build a wormhole?

The first step would be to find or create a region of spacetime that allows such geometry—a tunnel-like connection. This could involve collapsing matter into an ultra-dense configuration, manipulating fields with extreme precision, or harnessing quantum fluctuations.

Next, we’d need to stabilize it. That’s where exotic matter—or its equivalent—would come in. The amount required is staggering. Some estimates suggest it would take as much negative energy as the mass-energy of an entire star to keep a wormhole mouth open large enough for a spacecraft.

Then there’s control. The wormhole’s mouths must remain synchronized, protected from gravitational collapse, and shielded from external radiation. Navigating through one would require not only advanced propulsion but a deep understanding of how spacetime curves and responds to motion.

Even the smallest miscalculation could destroy the traveler—or the wormhole itself—in an instant.

So while the idea of wormhole travel captures our imagination, the engineering reality remains light-years beyond us.

Wormholes in Science Fiction and the Human Psyche

Though still theoretical, wormholes have already become icons in human storytelling. From Interstellar and Stargate to Doctor Who and Star Trek, they serve as portals not just through space, but through meaning.

In fiction, a wormhole represents the ultimate liberation from limits—the ability to transcend time, distance, and even death. It embodies our oldest human desire: to go beyond the horizon.

When we imagine stepping through a wormhole, we are not just dreaming of crossing galaxies. We are dreaming of transcending the barriers that bind us—space, time, ignorance, and mortality.

Science fiction gives emotional depth to what physics gives structure. Together, they create a dialogue between imagination and reality—a conversation that has driven discovery for centuries.

Could Nature Already Be Using Them?

Some physicists wonder whether wormholes might already exist in nature. If so, could we detect them?

One idea is that certain patterns of gravitational lensing—where light from distant stars bends around massive objects—might reveal the presence of a wormhole. If a wormhole connects two regions of the universe, light from the other side might leak through, creating strange optical effects.

Another possibility involves the mysterious phenomena of fast radio bursts (FRBs)—short, powerful flashes of radio waves from deep space. Some have speculated (though without evidence) that these could be signs of energy interacting through wormholes.

There’s even the idea that the supermassive black holes at galactic centers—like Sagittarius A* in our Milky Way—might conceal wormhole throats within their cores. If true, these cosmic giants could be gateways to other regions of the universe.

No evidence has yet supported these ideas, but the search continues. The universe is vast and mysterious, and nature often proves far more imaginative than we dare to believe.

Time, Paradox, and the Nature of Reality

If wormholes can connect not only distant places but different times, then our understanding of reality itself must change.

In such a universe, cause and effect are not absolute. The future can influence the past. Events can loop. The arrow of time becomes a circle.

Physicists have explored whether quantum mechanics might resolve such paradoxes through probabilities. In one interpretation, any action that could create a paradox simply results in a branching of timelines—a multiverse, where every possible outcome exists in its own universe.

In another view, the laws of physics might conspire to prevent paradoxical events altogether. You could travel back in time, but only in ways that preserve consistency—you might become part of the history you tried to change, not its destroyer.

These ideas stretch our logic, but they arise naturally from the equations that govern spacetime. The deeper we explore, the more we realize that reality may not be linear, but woven from countless threads of possibility.

The Philosophical Heart of the Question

Why do we care whether wormhole travel is possible?

Because the question touches something deep within the human spirit. It’s not just about faster travel—it’s about the meaning of boundaries.

Every scientific advance in history has been an act of rebellion against limitation. Fire, flight, space travel—all began with someone daring to ask “what if?” Wormholes represent the ultimate “what if”—the challenge to the very structure of space and time.

Even if we never build one, the pursuit itself is profoundly human. It reminds us that curiosity is not a luxury; it’s our defining trait. To seek wormholes is to seek ourselves—to test how far imagination and reason can go together.

The Universe and the Mirror of Our Ambition

Perhaps wormholes are not meant to be crossed, but contemplated. They remind us that the universe is stranger, subtler, and more beautiful than any mythology we’ve invented.

We may never walk through one, but understanding them changes us. It forces us to confront the vastness of existence, the fragility of our lives, and the audacity of our questions.

Maybe, in the end, wormholes are less about travel and more about connection. Between science and wonder. Between curiosity and humility. Between the infinite cosmos and the finite heart that dares to explore it.

The Final Horizon

Could humans ever travel through a wormhole?

For now, the honest answer is we don’t know. The equations say it might be possible, but nature’s verdict remains hidden. We lack the technology, the energy, and perhaps the understanding to build or survive such a journey.

Yet, the story is not over. Every great leap in science began with a question that once seemed impossible.

One day, perhaps millennia from now, humans may stand before the shimmering mouth of a real wormhole—built not of fantasy, but of mastery. They may step forward, hearts pounding, knowing they are crossing not just space, but the boundary between imagination and reality.

Until then, the dream continues.

Because as long as there are stars to reach and minds to wonder, we will keep asking, what lies on the other side?

And maybe—just maybe—the universe is waiting for us to find out.