Mercury is a world of paradoxes—small yet dense, scorched yet frozen, ancient yet surprisingly active. It races around the Sun at nearly 48 kilometers per second, completing an orbit in just 88 days. To the naked eye, it is elusive, often hidden in the Sun’s glare, visible only at dawn or dusk. Yet this tiny planet, the innermost of the Solar System, may hold some of the deepest secrets about our own planet’s beginnings.

For centuries, Mercury was little more than a distant mystery, glimpsed fleetingly through telescopes. Its proximity to the Sun made it one of the hardest planets to study from Earth. But in the past few decades, spacecraft missions such as NASA’s Mariner 10 and MESSENGER, and now ESA–JAXA’s BepiColombo, have transformed our understanding. Beneath its barren surface, Mercury hides the record of a violent and formative epoch in Solar System history—an epoch that may reveal how Earth itself came to be.

To understand our origins, we must look to the extremes, to the places where the laws of nature are written in stark clarity. Mercury is one such place. Its scorched plains, immense iron core, and chemical oddities challenge every conventional model of planet formation. Each crater and ridge tells a fragment of a larger cosmic story—the story of how the inner planets, including Earth, were forged from the dust and fire of the young Sun.

The Forgotten Planet

Mercury has often been overlooked. It is neither as beautiful as Venus nor as inviting as Mars. It lacks moons, clouds, or seasons. Yet its simplicity is deceptive. As the smallest planet, it is a survivor of a violent past. Its dense metallic core and thin silicate shell suggest that something extraordinary happened in its formation—something that stripped away much of its outer layers and left behind a remnant rich in iron and mystery.

Astronomers once thought Mercury was simply too close to the Sun to retain lighter materials, that solar heat and radiation blasted away its outer crust. But spacecraft data have shattered that notion. Mercury’s surface, while metal-rich, also contains unexpected elements such as sulfur, potassium, and sodium—materials that should have evaporated in the searing heat near the Sun. This paradox forces scientists to reconsider how the terrestrial planets, including Earth, were assembled.

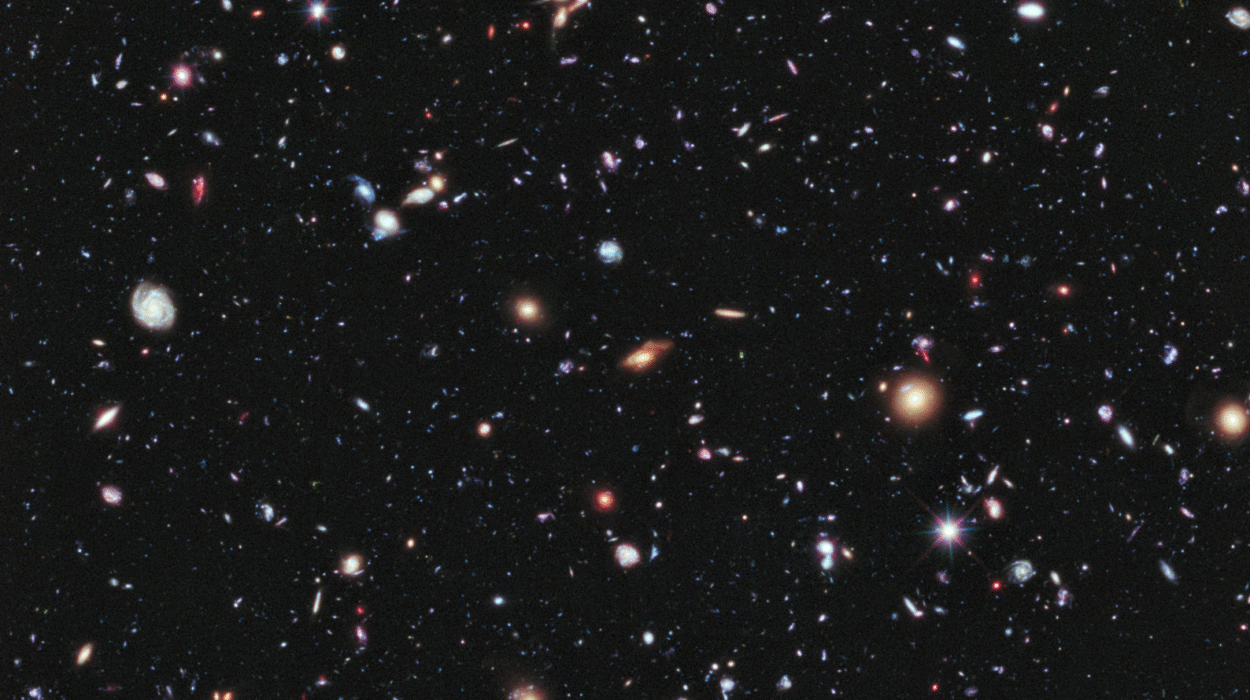

Understanding Mercury means peering back to the dawn of the Solar System, when dust and gas coalesced into planetesimals—the building blocks of worlds. In this chaotic era, collisions were frequent and catastrophic. Entire planets could be shattered, melted, or swallowed by others. Mercury, in its current form, may be the fossilized remnant of one such cosmic upheaval—a world sculpted by impact, heat, and chance.

A World of Metal

Mercury’s most striking feature is its extraordinary density. Despite being only 38 percent the size of Earth, it has a density nearly as high as ours. This means that, proportionally, Mercury contains far more metal than rock. Its iron core makes up about 85 percent of its radius—by far the largest core-to-mantle ratio of any planet in the Solar System.

Why is Mercury so metal-rich? Several hypotheses attempt to answer this. One suggests that a colossal impact early in its history stripped away much of its silicate crust and mantle, leaving behind the metallic heart. Another proposes that the young Sun’s intense radiation vaporized lighter elements from Mercury’s outer layers, selectively removing rock and leaving the heavier iron behind. A third possibility is that Mercury simply formed in a region of the solar nebula that was naturally rich in metallic material.

Each of these scenarios has profound implications for Earth’s own story. If Mercury was shaped by a giant impact, that event mirrors the collision thought to have formed Earth’s Moon. If solar radiation played a role, it tells us about how the Sun’s early activity influenced planetary chemistry. And if local composition determined Mercury’s makeup, it suggests that even small differences in the early Solar System’s temperature and dust distribution could produce wildly different worlds.

The Messenger’s Revelation

The first close-up look at Mercury came in 1974, when NASA’s Mariner 10 spacecraft flew past the planet three times, capturing about 45 percent of its surface. What it revealed astonished scientists. Mercury was covered in craters, resembling Earth’s Moon, but also displayed vast plains, long ridges, and cliffs called lobate scarps—evidence that the entire planet had shrunk as its core cooled.

Three decades later, NASA’s MESSENGER mission (MErcury Surface, Space ENvironment, GEochemistry, and Ranging) transformed our understanding once again. Launched in 2004 and entering orbit in 2011, MESSENGER mapped Mercury’s entire surface and measured its magnetic field, gravity, and composition in exquisite detail.

The findings were startling. Mercury’s surface was not as depleted in volatile elements as expected. Its magnetic field, though weak, was still active—suggesting that at least part of its iron core remains molten. Its crust contained sulfur in concentrations far higher than any other terrestrial planet. And its polar regions, hidden in permanent shadow, contained deposits of water ice.

These discoveries forced scientists to rethink the early Solar System. Mercury, it seemed, was not a simple relic scorched by the Sun. It was a complex, chemically diverse world—one that formed under conditions unlike any other.

The Puzzle of the Core

Mercury’s massive core remains one of planetary science’s greatest enigmas. It may hold the key not only to understanding Mercury’s evolution but also to deciphering how planets like Earth acquired their metallic hearts.

The presence of a global magnetic field on Mercury was one of MESSENGER’s most surprising findings. The field, though only about one percent as strong as Earth’s, indicates that Mercury’s core is at least partially liquid. This is unexpected for such a small planet, which should have cooled and solidified long ago.

One explanation is that the high sulfur content in Mercury’s core lowers its melting point, allowing it to remain fluid. Another possibility is that Mercury’s core still retains residual heat from its violent formation. Either way, the persistence of an active dynamo inside Mercury gives scientists valuable clues about the thermal evolution of rocky planets, including Earth.

The contrast between Mercury’s oversized core and its thin crust also raises intriguing questions. Why did Earth, Venus, and Mars develop thicker mantles and crusts while Mercury remained mostly metallic? Was the distribution of materials in the early Solar System uneven? Did Mercury form from a different mixture of dust and gas, or was it violently reshaped after its birth? Each hypothesis carries implications for the broader mystery of how terrestrial planets differentiate—how they separate into core, mantle, and crust.

Echoes of Earth’s Formation

To understand how Mercury might reveal Earth’s origins, we must return to the Solar System’s formative period, about 4.6 billion years ago. In the swirling protoplanetary disk surrounding the newborn Sun, dust grains began to stick together, forming pebbles, then planetesimals, and eventually protoplanets. This process, called accretion, built the terrestrial worlds from the inside out.

But the environment near the Sun was far from tranquil. Temperatures were high, radiation intense, and gravitational interactions chaotic. Collisions between young planets were common. Some merged; others were obliterated. The boundaries between formation and destruction were razor-thin.

In this cosmic furnace, Mercury may represent a fossilized fragment of those earliest epochs—a planet whose composition preserves the chemistry of the inner solar nebula. Its abundance of iron and sulfur, for example, suggests that it formed in a region where metal condensed more readily than silicate rock. By studying Mercury’s elemental makeup, scientists can infer the temperature, pressure, and oxidation conditions that prevailed when the terrestrial planets were born.

This, in turn, helps explain how Earth acquired its metallic core and silicate mantle. If Mercury formed under more reducing (oxygen-poor) conditions, it offers a natural comparison to Earth, which formed slightly farther out in a more oxidized region. The difference in these early environments may explain why Earth retained water and a thick atmosphere while Mercury became desiccated and barren.

The Clues Hidden in Chemistry

The chemistry of Mercury’s surface is like a coded message from the past. MESSENGER’s spectrometers detected high levels of elements such as sulfur, chlorine, potassium, and sodium—substances that should have been lost if Mercury had formed in extreme heat. This contradiction implies that either Mercury formed farther from the Sun and migrated inward or that the inner Solar System’s early environment was cooler than models suggest.

These findings challenge long-standing assumptions about planetary differentiation. For instance, Earth’s mantle is relatively oxidized, meaning that metals like iron and nickel combined with oxygen to form oxides. Mercury’s mantle, in contrast, appears highly reduced, indicating that its metals remained in pure or sulfide form. This difference may reflect the gradient of chemical conditions in the early solar nebula—a gradient that shaped the diversity of terrestrial planets.

Moreover, the presence of water-related minerals in Mercury’s polar craters reveals that even this scorched world has preserved traces of volatile compounds. This discovery echoes the idea that water and organic molecules were more widespread in the early Solar System than once thought. Understanding how these materials were retained—or lost—by Mercury may illuminate how Earth became the oasis of life it is today.

Mercury’s Shrinking Skin

One of Mercury’s most distinctive geological features is its system of long, curving cliffs, or lobate scarps. These structures, some hundreds of kilometers long and several kilometers high, formed as the planet’s interior cooled and contracted. Like a drying apple, Mercury’s surface wrinkled as it shrank.

This global contraction, estimated to have reduced Mercury’s radius by about seven kilometers, offers direct evidence of planetary cooling. On Earth, tectonic activity renews the crust and masks such large-scale contraction. But Mercury, geologically quiet for billions of years, preserves its ancient scars.

By studying these features, scientists can estimate how fast Mercury’s core cooled and how its magnetic field evolved over time. This, in turn, helps refine models of planetary heat flow and magnetic dynamo generation—key processes that also shaped Earth’s internal structure. In this sense, Mercury acts as a natural laboratory for understanding how planets lose heat, how their cores solidify, and why some retain magnetic fields while others do not.

A Planet of Extremes

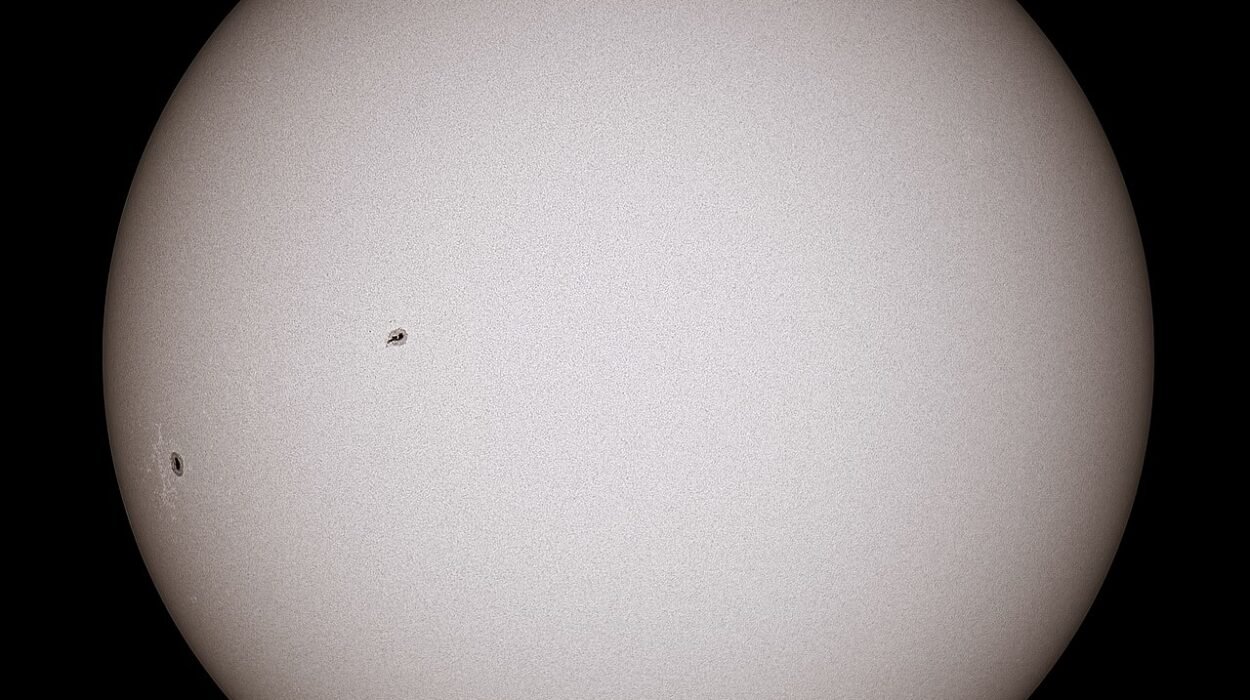

Mercury’s environment is as harsh as any in the Solar System. By day, the Sun blazes with 11 times the intensity it does on Earth, heating the surface to over 430°C. By night, without an atmosphere to trap heat, temperatures plummet to -180°C. This wild swing, greater than any other planet experiences, demonstrates what happens when a world lacks the insulating blanket of air that Earth enjoys.

The planet’s tenuous exosphere—an ultra-thin atmosphere composed of atoms sputtered from the surface by solar wind—offers a glimpse of the early Solar System’s raw interactions. Studying this exosphere reveals how solar radiation and particle bombardment can strip planets of their atmospheres over time. For Earth, which once faced similar processes, Mercury serves as both a cautionary tale and a comparative benchmark.

Even in such extremes, Mercury displays surprising beauty. Its sky, perpetually black, frames a Sun that appears twice as large as from Earth. The planet’s long days—each lasting 176 Earth days from sunrise to sunrise—create surreal rhythms of light and shadow. For scientists, these extremes are not deterrents but clues, revealing how proximity to the Sun shapes the evolution of planetary surfaces and atmospheres.

The New Frontier: BepiColombo

Today, the European and Japanese BepiColombo mission is continuing the exploration of Mercury. Launched in 2018, it carries two spacecraft: ESA’s Mercury Planetary Orbiter and JAXA’s Mercury Magnetospheric Orbiter. Together, they will study Mercury’s surface, interior, magnetic field, and exosphere in unprecedented detail once they enter orbit around 2026.

One of BepiColombo’s goals is to refine our understanding of Mercury’s origin and evolution. Its instruments will measure the planet’s gravitational field to map internal structures, analyze surface composition to identify chemical anomalies, and study how solar wind interacts with the planet’s magnetic field. The mission may finally help answer why Mercury is so iron-rich and what that means for Earth’s own composition.

If Mercury’s peculiar chemistry and structure can be traced to conditions in the early solar nebula, BepiColombo could provide a blueprint for understanding not just Earth, but all rocky planets in and beyond our Solar System. By decoding Mercury’s story, we may learn how common Earth-like worlds truly are—and whether our planet’s path was inevitable or unique.

Mercury as a Window into Planetary Diversity

Comparing Mercury to Earth and its siblings reveals the astonishing diversity of outcomes that can arise from similar beginnings. Venus and Earth are nearly twins in size and mass, yet one became a greenhouse inferno while the other nurtured life. Mars, once warm and wet, is now frozen and dry. And Mercury, the smallest of all, turned out to be a metal giant.

This diversity underscores a fundamental truth: small differences in initial conditions—distance from the Sun, chemical composition, impact history—can yield dramatically different worlds. Mercury, by existing at one extreme, helps define the boundaries of what is possible.

Moreover, studying Mercury informs our search for exoplanets. Many planets discovered around other stars are “super-Mercuries”—dense, metal-rich worlds orbiting close to their suns. Understanding Mercury’s evolution helps astronomers interpret these distant systems and assess how often rocky planets like Earth might emerge in the cosmos.

Lessons for Earth’s Future

Beyond its role as a window into the past, Mercury also offers insight into planetary futures. Its barren surface and vanished atmosphere illustrate the long-term effects of solar radiation and internal cooling. As the Sun gradually brightens over billions of years, Earth too will face increasing heat. Studying Mercury helps scientists predict how planets respond to changing solar conditions—how atmospheres erode, how surfaces age, and how magnetic fields fade.

Mercury’s history also reminds us of the delicate balance that sustains habitability. Its lack of a significant atmosphere and magnetic shield allowed solar winds to strip volatile elements away, leaving a lifeless world. Earth, by contrast, retained a magnetic field generated by its molten core—a protection that preserves our air and oceans. Understanding why Mercury’s field weakened while Earth’s persisted can illuminate the factors that determine a planet’s ability to remain habitable over geological time.

The Mirror of Creation

In a cosmic sense, Mercury is both a relic and a mirror—a relic of the Solar System’s violent youth and a mirror reflecting the forces that shaped Earth. Its surface records the last stages of accretion, when impacts forged and sculpted the inner planets. Its chemistry preserves the signature of the primordial solar nebula. Its shrunken, iron heart offers a glimpse into the deep processes that forged Earth’s own core.

When scientists look at Mercury, they see not just a desolate world but a memory of creation itself. Every crater, ridge, and element tells part of the story of how raw cosmic material became a living planet. In that sense, Mercury is not alien—it is kin. It carries within it the same stardust and energy that gave rise to Earth and all that inhabits it.

The Mystery Endures

Despite decades of exploration, Mercury remains a world of unanswered questions. Why does it have such a disproportionately large core? How did it retain volatile materials so close to the Sun? Why does it still possess a magnetic field when larger planets like Mars do not? Each question brings us closer to understanding not just Mercury, but the processes that built every rocky planet, including our own.

The answers may not come easily. Mercury challenges our models, forcing us to confront the limits of our knowledge. But that challenge is what makes it invaluable. In the silence of its scorched plains, Mercury holds the secrets of cosmic beginnings—the blueprint from which Earth itself was drawn.

The First Step Toward Home

To explore Mercury is, paradoxically, to come closer to understanding Earth. Its iron heart and volatile chemistry, its battered crust and lingering magnetism—all are echoes of what once shaped our own planet. By decoding those echoes, scientists hope to retrace the steps of creation, to see how chaos became order, how dust became worlds, how worlds became alive.

Mercury stands as both the first planet and, in a way, the first chapter—a prologue to the story of Earth. It reminds us that even the smallest worlds can hold the grandest truths. As we send new missions to probe its secrets, we are not merely studying a distant sphere of rock and metal; we are listening to the whispers of our own origin.

In the glare of the Sun, Mercury endures—scarred, silent, enduring. It has survived the violence that birthed the Solar System, carrying within its iron heart the memory of creation. One day, when we fully understand its story, we may finally understand how Earth was born—and, in that knowledge, glimpse the deeper logic of the universe that made both possible.

The Planet That Remembers

Mercury may be small, but it is the keeper of our past. It is the ancient witness that saw the Solar System ignite, the planets collide, and the Earth emerge from chaos. While it spins silently in its tight orbit, it carries the fingerprints of all that came before.

To look upon Mercury, then, is to look backward in time—to the moment when the Solar System was still molten, when planets were possibilities, and when the ingredients of life were being mixed in cosmic proportions. It is the first planet, the oldest memory, the echo of a beginning we still strive to comprehend.

And so, when scientists ask whether Mercury can reveal clues about Earth’s birth, the answer is yes—not just in chemistry or geology, but in essence. Mercury is the fossil of our cosmic childhood, the metallic whisper of creation’s furnace. It stands closest to the Sun, yet closest, too, to the moment when light first fell upon the newborn Earth.

In its small, brilliant sphere, Mercury carries the key to our origin—a reminder that to know where we came from, we must listen to the quiet voices of the worlds that came before.